Battle of Passchendaele

The third major battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, took place between July and November, 1917. General Sir Douglas Haig, the British Commander in Chief in France, was encouraged by the gains made at the offensive at Messines. Haig was convinced that the German army was now close to collapse and once again made plans for a major offensive to obtain the necessary breakthrough. The official history of the battle claimed Haig's plan "may seem super-optimistic and too far-reaching, even fantastic". Many historians have suggested that the main problem was that Haig "had chosen a field of operations where the preliminary bombardment churned the Flanders plain into impassable mud." (1)

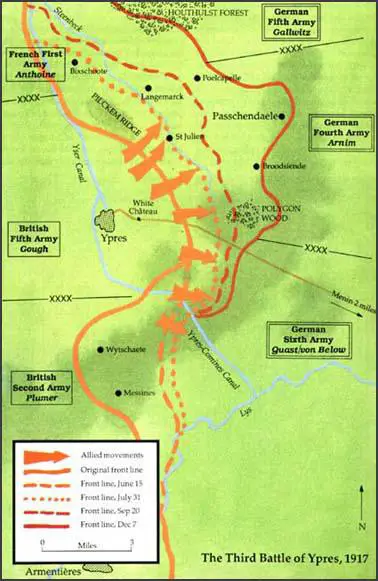

The opening attack at Passchendaele was carried out by General Hubert Gough and the British Fifth Army with General Herbert Plumer and the Second Army joining in on the right and General Francois Anthoine and the French First Army on the left. After a 10 day preliminary bombardment, with 3,000 guns firing 4.25 million shells, the British offensive started at Ypres a 3.50 am on 31st July.

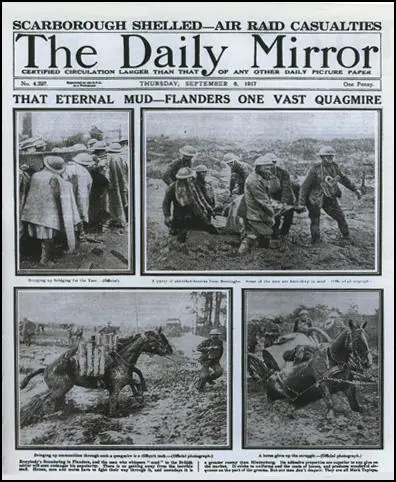

Allied attacks on the German front-line continued despite very heavy rain that turned the Ypres lowlands into a swamp. The situation was made worse by the fact that the British heavy bombardment had destroyed the drainage system in the area. This heavy mud created terrible problems for the infantry and the use of tanks became impossible.

Percival Phillips of The Daily Express commented: "The weather changed for the worse last night, although fortunately too late to hamper the execution of our plans. The rain was heavy and constant throughout the night. It was still beating down steadily when the day broke chill and cheerless, with a thick blanket of mist completely shutting off the battlefield. During the morning it slackened to a dismal drizzle, but by this time the roads, fields, and footways were covered with semi-liquid mud, and the torn ground beyond Ypres had become in places a horrible quagmire." (2)

As William Beach Thomas, a journalist working for the Daily Mail, pointed out: "Floods of rain and a blanket of mist have doused and cloaked the whole of the Flanders plain. The newest shell-holes, already half-filled with soakage, are now flooded to the brim. The rain has so fouled this low, stoneless ground, spoiled of all natural drainage by shell-fire, that we experienced the double value of the early work, for today moving heavy material was extremely difficult and the men could scarcely walk in full equipment, much less dig. Every man was soaked through and was standing or sleeping in a marsh. It was a work of energy to keep a rifle in a state fit to use." (3)

On 31st July 1917, Lieutenant Robert Sherriff and his men of the the East Surrey Regiment were called forward to attack the German positions. "The living conditions in our camp were sordid beyond belief. The cookhouse was flooded, and most of the food was uneatable. There was nothing but sodden biscuits and cold stew. The cooks tried to supply bacon for breakfast, but the men complained that it smelled like dead men.... At dawn on the morning of the attack, the battalion assembled in the mud outside the huts. I lined up my platoon and went through the necessary inspection. Some of the men looked terribly ill: grey, worn faces in the dawn, unshaved and dirty because there was no clean water. I saw the characteristic shrugging of their shoulders that I knew so well. They hadn't had their clothes off for weeks, and their shirts were full of lice." (4)

In the first few days of fighting the Allies suffered about 35,000 killed and wounded. Haig described the situation as "highly satisfactory" and "the losses slight". David Lloyd George was furious and met with Sir William Robertson, the Chief of Staff, and complained about "the futile massacre... piled up the ghastly hecatombs of slaughter". Lloyd George repeatedly told Robertson that the offensive must be "abandoned as soon as it became evident that its aims were unattainable." (5)

A copy of this newspaper can be obtained from Historic Newspapers.

The German Fourth Army held off the main British advance and restricted the British to small gains on the left of the line. Eventually, General Haig called off the attacks and did not resume the offensive until 26th September. These attacks enabled the British forces to take possession of the ridge east of Ypres. Despite the return of heavy rain, Haig ordered further attacks towards the Passchendaele Ridge. Attacks on the 9th and 12th October were unsuccessful. As well as the heavy mud, the advancing British soldiers had to endure mustard gas attacks. This gas caused particular problems, because its odour was not very strong. (6)

Three more attacks took place in October and on the 6th November the village of Passchendaele was finally taken by British and Canadian infantry. Sir Douglas Haig was severely criticized for continuing with the attacks long after the operation had lost any real strategic value. Since the beginning of the offensive, British troops had advanced five miles at a cost of at least 250,000 casualties, though some authorities say 300,000. "Certainly 100,000 of them occurred after Haig's insistence on continuing the fighting into October. German losses over the whole of the Western Front for the same period were about 175,000." (7)

Primary Sources

(1) William Beach Thomas, Daily Mail (2nd August, 1917)

Floods of rain and a blanket of mist have doused and cloaked the whole of the Flanders plain. The newest shell-holes, already half-filled with soakage, are now flooded to the brim. The rain has so fouled this low, stoneless ground, spoiled of all natural drainage by shell-fire, that we experienced the double value of the early work, for today moving heavy material was extremely difficult and the men could scarcely walk in full equipment, much less dig. Every man was soaked through and was standing or sleeping in a marsh. It was a work of energy to keep a rifle in a state fit to use.

(2) Percival Phillips, Daily Express (2nd August, 1917)

The weather changed for the worse last night, although fortunately too late to hamper the execution of our plans. The rain was heavy and constant throughout the night. It was still beating down steadily when the day broke chill and cheerless, with a thick blanket of mist completely shutting off the battlefield. During the morning it slackened to a dismal drizzle, but by this time the roads, fields, and footways were covered with semi-liquid mud, and the torn ground beyond Ypres had become in places a horrible quagmire.

It was pretty bad in the opinion of the weary soldiers who came back with wounds, but it was certainly worse for the enemy holding fragments of broken lines still heavily hammered by the artillery and undoubtedly disheartened by the hardships of a wet night in the open after a day of defeat.

(3) Percival Phillips, Daily Express (17th August, 1917)

I talked today with a number of wounded men engaged in the fighting in Langemark and beyond, and they are unanimous in declaring that the enemy infantry made a very poor show wherever they were deprived of their supporting machine guns and forced to choose between meeting a bayonet charge and fight. The mud was our men's greatest grievance. It clung to their legs at every step. Frequently they had to pause to pull their comrades from the treacherous mire - figures embedded to the waist, some of them trying to fire their rifles at a spitting machine gun and yet, despite these almost incredible difficulties, they saved each other and fought the Hun through the floods to Langemarck.

(4) Philip Gibbs, Adventures in Journalism (1923)

Every man of ours who fought on the way to Passchendaele agreed that those battles in Flanders were the most awful, the most bloody, and the most hellish. The condition of the ground, out from Ypres and beyond the Menin Gate, was partly the cause of the misery and the filth. Heavy rains fell, and made one great bog in which every shell crater was a deep pool. There were thousands of shell craters. Our guns had made them, and German gunfire, slashing our troops, made thousands more, linking them together so that they were like lakes in some places, filled with slimy water and dead bodies. Our infantry had to advance heavily laden with their kit, and with arms and hand-grenades and entrenching tools - like pack animals - along slimy duckboards on which it was hard to keep a footing, especially at night when the battalions were moved under cover of darkness.

(5) Robert Sherriff, No Leading Lady (1968)

At dawn on the morning of the attack, the battalion assembled in the mud outside the huts. I lined up my platoon and went through the necessary inspection. Some of the men looked terribly ill: grey, worn faces in the dawn, unshaved and dirty because there was no clean water. I saw the characteristic shrugging of their shoulders that I knew so well. They hadn't had their clothes off for weeks, and their shirts were full of lice.

Our progress to the battle area was slow and difficult. We had to move forward in single file along the duckboard tracks that were loose and slimy. If you slipped off, you went up to your knees in mud.

During the walk the great bombardment from the British guns fell silent. For days it had wracked our nerves and destroyed our sleep. The sudden silence was uncanny. A sort of stagnant emptiness surrounded us. Your ears still sang from the incessant uproar, but now your mouth went dry. An orchestral overture dies away in a theatre as the curtain rises, so the great bombardment faded into silence as the infantry went into the attack. We knew now that the first wave had left the British front-line trenches, that we were soon to follow...

All of us, I knew, had one despairing hope in mind: that we should be lucky enough to be wounded, not fatally, but severely enough to take us out of this loathsome ordeal and get us home. But when we looked across that awful slough ahead of us, even the thought of a wound was best forgotten. If you were badly hit, unable to move, what hope was there of being carried out of it? The stretcher bearers were valiant men, but there were far too few of them...

The order came to advance. There was no dramatic leap out of the trenches. The sandbags on the parapet were so slimy with rain and rotten with age that they fell apart when you tried to grip them. You had to crawl out through a slough of mud. Some of the older men, less athletic than the others, had to be heaved out bodily.

From then on, the whole thing became a drawn-out nightmare. There were no tree stumps or ruined buildings ahead to help you keep direction. The shelling had destroyed everything. As far as you could see, it was like an ocean of thick brown porridge. The wire entanglements had sunk into the mud, and frequently, when you went in up to the knees, your legs would come out with strands of barbed wire clinging to them, and your hands torn and bleeding through the struggle to drag them off...

All this area had been desperately fought over in the earlier battles of Ypres. Many of the dead had been buried where they fell and the shells were unearthing and tossing up the decayed bodies. You would see them flying through the air and disintegrating...

In the old German trench we came upon a long line of men, some lolling on the fire step, some sprawled on the ground, some standing upright, leaning against the trench wall. They were British soldiers - all dead or dying. Their medical officer had set up a first-aid station here, and these wounded men had crawled to the trench for his help. But the doctor and his orderlies had been killed by a shell that had wrecked his station, and the wounded men could only sit or lie there and die. There was no conceivable hope of carrying them away.

We came at last to some of the survivors of the first wave. They had reached what had once been the German support line, still short of their objective. An officer said, "I've got about fifteen men here. I started with a hundred. I don't know where the Germans are." He pointed vaguely out across the land ahead.

"They're somewhere out there. They've got machine guns, and you can see those masses of unbroken barbed wire. It's useless to go on. The best you can do is to bring your men in and hold the line with us."

We were completely isolated. The only communication with the rear was to scribble messages in notebooks and give them to orderlies to take back. But the orderlies wouldn't have the faintest idea where the nearest command post was, even if they survived.

We found an old German shelter and brought into it all our wounded that we could find. We carried pocket first-aid dressings, but the small pads and bandages were useless on great gaping wounds. You did what you could, but it was mainly a matter of watching them slowly bleed to death...

It came to an end for me sometime that afternoon. For an hour or more we waited in that old German trench. Sometimes a burst of machine-gun bullets whistles overhead, as if the Germans were saying, "Come on if you dare".

Our company commander had made his headquarters under a few sheets of twisted corrugated iron.

"I want you to explore along the trench,' he (Warre-Dymond) said to me, and see whether you can find B Company (it was in fact D Company). They started off on our right flank, but I haven't seen anything of them since. If you can find them, we can link up together and get some sort of order into things.'

So I set off with my runner. It was like exploring the mountains of the moon. We followed the old trench as best we could...

We heard the thin whistle of its approach, rising to a shriek. It landed on top of a concrete pillbox that we were passing, barely five yards away. A few yards further, and it would have been the end of us. The crash was deafening. My runner let out a yell of pain. I didn't yell so far as I know because I was half-stunned. I remember putting my hand to the right side of my face and feeling nothing; to my horror I thought that the whole side had been blown away.

(6) Harry Patch, Last Post (2005)

On my nineteenth birthday, 17 June 1917, we were in the trenches at Passchendaele. We didn't go into action, but I saw it all happen. Haig put a three-day barrage on the Germans, and thought, 'Well, there can't be much left of them.' I think it was the Yorkshires and Lancashires that went over. I watched them as they came out of their dugouts and the German machine guns just mowed them down. I doubt whether any of them reached the front line.

A couple of weeks after that we moved to Pilckem Ridge. I can still see the bewilderment and fear on the men's faces as we went over the top. We crawled because if you stood up you'd be killed. All over the battlefield the wounded were lying there, English and German, all crying for help. But we weren't like the Good Samaritan in the Bible, we were the robbers who passed by and left them. You couldn't stop to help them. I came across a Cornishman who was ripped from shoulder to his waist with shrapnel, his stomach on the ground beside him. A bullet wound is clean - shrapnel tears you all to pieces. As I got to him he said, 'Shoot me.' Before I could draw my revolver, he died. I was with him for the last sixty seconds of his life. He gasped one word -'Mother'. That one word has run through my brain for eighty-eight years. I will never forget it. I think it is the most sacred word in the English language. It wasn't a cry of distress or pain - it was one of surprise and joy. I learned later that his mother was already dead, so he felt he was going to join her.

We got as far as their second line and four Germans stood up. They didn't get up to run away, they got up to fight. One of them came running towards me. He couldn't have had any ammunition or he would have shot me, but he came towards me with his bayonet pointing at my chest. I fired and hit him in the shoulder. He dropped his rifle, but still came stumbling on. I can only suppose that he wanted to kick our Lewis Gun into the mud, which would have made it useless. I had three live rounds left in my revolver and could have killed him with the first. What should I do? I had seconds to make my mind up. I gave him his life. I didn't kill him. I shot him above the ankle and above the knee and brought him down. I knew he would be picked up, passed back to a POW camp, and at the end of the war he would rejoin his family. Six weeks later, a countryman of his killed my three mates. If that had happened before I met that German, I would have damn well killed him. But we never fired to kill. My Number One, Bob, used to keep the gun low and wound them in the legs - bring them down. Never fired to kill them. As far as I know he never killed a German. I never did either. Always kept it low.

Student Activities

Sinking of the Lusitania (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)