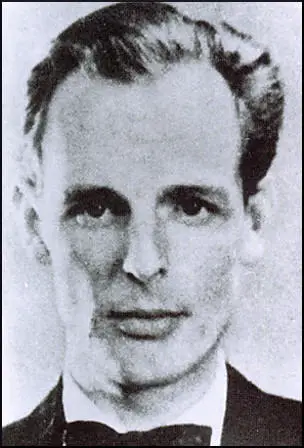

Donald Maclean

Donald Maclean, the son of the Liberal cabinet minister, Donald Maclean, was born in London on 25th May, 1913. He was educated at Gresham's School. His friend and biographer, Robert Cecil, has suggested "Maclean was educated at Gresham's School, Holt, where the headmaster, J. R. Eccles, enforced the so-called 'honour system’ with the aim of maintaining the highest moral standards. It may well be supposed that this system, allied to a strict upbringing at the hands of Sir Donald, a non-smoker, temperance advocate, and severe sabbatarian, may have brought out in his son the tendency both to rebel and to deceive authority." (1)

In October 1931 went to Trinity College to study modern languages. The death of his father in 1932 he moved sharply to the left. He joined the Cambridge University Socialist Society (CUSS) and most of his new friends held radical political views. This included Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt, Kim Philby and James Klugmann. According to Christopher Gillie, who arrived at Cambridge University in October 1932: "I saw a good deal of him after his father's death and he was cheerfully open now about his unreserved allegiance to the Communist cause." (2)

Donald Maclean and Communism

Maclean and Klugmann joined the Communist Party of Great Britain: "They spent much of their time working for the part, organizing study groups, and trying to get Marxism accepted as a philosophy in the university curriculum... They kept lists of fellow-travellers and sympathizers and devoted a lot of effort to recruiting. They attacked the CUSS for being weak-kneed, screaming and shouting at political debates in a manner Cambridge had never seen before but which the students tolerated because of their obvious conviction." (3)

Donald Maclean made it clear that he knew exactly what was wong with contemporary Britain: "The economic situation, the unemployed, vulgarity in the cinema, rubbish on the bookstalls, the public school, snobbery in the suburbs, more battleships, lower wages." The major problem was capitalism and he argued that communism was going to sweep away "the whole crack-brained, criminal mess". (4)

Arnold Deutsch

In January 1934 Arnold Deutsch, one of NKVD's agents, was sent to London. As a cover for his spying activities he did post-graduate work at London University. In May he made contact with Litzi Friedmann and Edith Tudor Hart. They discussed the recruitment of Soviet spies. Litzi suggested her husband, Kim Philby. "According to her report on Philby's file, through her own contacts with the Austrian underground Tudor Hart ran a swift check and, when this proved positive, Deutsch immediately recommended... that he pre-empt the standard operating procedure by authorizing a preliminary personal sounding out of Philby." (5)

Philby later recorded that in June 1934. "Lizzy came home one evening and told me that she had arranged for me to meet a 'man of decisive importance'. I questioned her about it but she would give me no details. The rendezvous took place in Regents Park. The man described himself as Otto. I discovered much later from a photograph in MI5 files that the name he went by was Arnold Deutsch. I think that he was of Czech origin; about 5ft 7in, stout, with blue eyes and light curly hair. Though a convinced Communist, he had a strong humanistic streak. He hated London, adored Paris, and spoke of it with deeply loving affection. He was a man of considerable cultural background." (6)

Deutsch asked Philby if he was willing to spy for the Soviet Union: "Otto spoke at great length, arguing that a person with my family background and possibilities could do far more for Communism than the run-of-the-mill Party member or sympathiser... I accepted. His first instructions were that both Lizzy and I should break off as quickly as possible all personal contact with our Communist friends." It is claimed by Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009) that Philby became the first of "the ablest group of British agents ever recruited by a foreign intelligence service." (7)

The Foreign Office

In June 1934 Donald Maclean graduated with first class honours. Maclean told his friends that he intended to visit the Soviet Union and undertake voluntary work as a teacher or tractor driver. However, his widowed mother, encouraged him to join the British diplomatic service. He finally agreed to this and in the Foreign Office examination he was among the first half dozen successful candidates. According to his friend, Cressida Bonham Carter, he was asked in his interview: "By the way, Mr Maclean. We understand that you, like other young men, held strong Communist views while you were at Cambridge. Do you still hold those views?" He replied: "I did have such views - and I haven't entirely shaken them off." Maclean later recalled: "I think they must have liked my honesty because they nodded, looked at each other and smiled." Maclean was accepted into the diplomatic service. (8)

Soon after being accepted into the Foreign Office, Arnold Deutsch asked Kim Philby to make a list of potential recruits. The first person he approached was his friend, Donald Maclean. Philby invited him to dinner, and hinted that there was important clandestine work to be done on behalf of the Soviet Union. He told him that "the people I could introduce you to are very serious." Maclean agreed to met Deutsch. He was told to carry a book with a bright yellow cover into a particular café at a certain time. Deutsch was impressed with Maclean who he described as being "very serious and aloof" with "good connections". Maclean was given the codename "Orphan". (9) Maclean was also ordered to give up his communist friends.

Philby Spy Network

Donald Maclean suggested to Deutsch that he met another one of his CUSS friends, Guy Burgess. (10) At first Deutsch rejected Burgess as a potential spy. He reported to headquarters that Burgess was "very smart... but a bit superficial and could let slip in some circumstances." Burgess began to suspect that his friend Maclean was working for the Soviets. He told Maclean: "Do you think that I believe for even one jot that you have stopped being a communist? You're simply up to something." (11) When Maclean told Deutsch about the conversation, he reluctantly signed him up. Burgess went around telling anyone who would listen that he had swapped Karl Marx for Benito Mussolini and was now a devotee of Italian fascism. (12)

Burgess now suggested the recruitment of one of his friends, Anthony Blunt. According to Blunt's biographer, Michael Kitson: "Blunt - hitherto the image of an elegant, apolitical, social young academic - began to take an interest in Marxism under the influence of his friend the charming, scandalous Guy Burgess, a fellow Apostle, who had recently converted to communism. Blunt's move to the left can be plotted in his art reviews, in which he turned from a Bloomsbury acolyte into an increasingly dogmatic defender of social realism. He eventually came to attack even his favourite contemporary artist, Picasso, for the painting Guernica's insufficient incorporation of communism." (13)

Other friends, John Cairncross and Michael Straight were also recruited during this period. Arnold Deutsch handled recruitment but much of the day-to-day management of the spies were carried out by another agent, Theodore Maly. Born in Timişoara, Romania, he studied theology and became a priest but on the outbreak of the First World War he joined the Austro-Hungarian Army. He told Elsa Poretsky, the wife of Ignaz Reiss: "During the war I was a chaplain, I had just been ordained as a priest. I was taken prisoner in the Carpathians. I saw all the horrors, young men with frozen limbs dying in the trenches. I was moved from one camp to another and starved along with other prisoners. We were all covered with vermin and many were dying of typhus. I lost my faith in God and when the revolution broke out I joined the Bolsheviks. I broke with my past completely. I was no longer a Hungarian, a priest, a Christian, even anyone's son. I became a Communist and have always remained one." (14)

Christopher Andrew has argued in his book, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009): "KGB files credit Deutsch with the recruitment of twenty agents during his time in Britain. The most successful, however, were the Cambridge Five: Philby, Maclean, Burgess, Blunt and Cairncross.... All were committed ideological spies inspired by the myth-image of Stalin's Russia as a worker-peasant state with social justice for all rather than by the reality of a brutal dictatorship with the largest peacetime gulag in European history. Deutsch shared the same visionary faith as his Cambridge recruits in the future of a human race freed from the exploitation and alienation of the capitalist system. His message of liberation had all the greater appeal for the Five because it had a sexual as well as a political dimension. All were rebels against the strict sexual mores as well as the antiquated class system of inter war Britain. Burgess and Blunt were gay and Maclean bisexual at a time when homosexual relations, even between consenting adults, were illegal. Cairncross, like Philby a committed heterosexual, later wrote a history of polygamy." (15)

Diplomatic Career

In 1938 Maclean was appointed third secretary at the Paris embassy. There he met an American student, Melinda Marling, eldest daughter of Francis Marling, a Chicago businessman. According to Robert Cecil: "Donald (who was bisexual) and Melinda were married in Paris." (16) The following year Walter Krivitsky, a senior Soviet intelligence officers, who had defected to the West, was brought to London to be interviewed by Dick White and Guy Liddell of MI5. When Kim Philby heard about this he began to fear for Maclean's safety. He later wrote in My Secret War (1968): "I recalled the statement of Krivitsky to the best of my ability from memory. He had said that the head of Soviet intelligence for Western Europe had recruited in the middle thirties a young man who had gone into the Foreign Office. He was of good family and had been educated at Eton and Oxford. He was an idealist, working without payment." (17)

Krivitsky gave details of 61 agents working in Britain. This included John Herbert King (MAG) and Henri Pieck (COOPER). He did not always know the names of these agents but described one, codename - STUART, as "a Scotsman of good family, educated at Eton and Oxford, and an idealist who worked for the Russians without payment." This descriptions fitted Donald Maclean. However, White and Liddle were not convinced by Krivitsky's testimony and his leads were not followed up. (18)

When the German Army invaded France in May 1940 Maclean returned to London. In May 1944 he was given the post of First Secretary to the German Department of the British Embassy in Washington. While in this post he passed vital documents on nuclear planning to the Soviet Union. His biographer has pointed out: "For some months in 1946 Maclean was acting head of chancery; but his most important duties, from the NKVD's viewpoint, were connected with the development of the atom bomb. Early in 1947 he became joint secretary of the Anglo-American-Canadian Combined Policy Committee, a post that gave him access to the American atomic energy commission at a time when the American government was making maximum efforts to prevent leakage of information about nuclear weapons." (19)

After the Second World War Maclean worked in London before holding a senior post in the British Embassy in Egypt. Friens explained that his behaviour was very erratic. This was put down to his heavy drinking. Philip Toynbee later wrote in his diary: "Extraordinary conversation with Donald. I find him more and more fascinating and delightful. His extreme gentleness and politeness - the occasional berserk and murderous outbursts when, so to speak, the pot of suppressed anger has been filled." On another occasion, when Maclean had been drunk, he confessed to Toynebee: "Donald told me he wished, still, for the death of his wife. He was in a queer and terrifying condition." (20)

Donald Maclean & Guy Burgess

In 1950 Guy Burgess was appointed the first secretary at the British embassy in Washington. The head of the network, Kim Philby, also worked in the city. He suggested to his wife, Aileen Philby, that Burgess should live in the basement of their house. Nicholas Elliott explained that Aileen was completely opposed to the idea. "Knowing the trouble that would inevitably ensue - and remembering Burgess's drunken and homosexual orgies when he had stayed with them in Instanbul - Aileen resisted this move, but bowed in the end (and as usual) to Philby's wishes... The inevitable drunken scenes and disorder ensued and tested the marriage to its limits." (21)

Meredith Gardner and his code-breaking team at Arlington Hall discovered that a Soviet spy with the codename of Homer was found on a number of messages from the KGB station at the Soviet consulate-general in New York City to Moscow Centre. The cryptanalysts discovered that the spy had been in Washington since 1944. The FBI concluded that it could be one of 6,000 people. At first they concentrated their efforts on non-diplomatic employees of the embassy. In April 1951, the Venona decoders found the vital clue in one of the messages. Homer had had regular contacts with his Soviet control in New York, using his pregnant wife as an excuse. This information enabled them to identify the spy as Donald Maclean, the first secretary at the Washington embassy during the Second World War. (22)

Kim Philby was told of the breakthrough. Philby took the news calmly as there was no real evidence, as yet, to connect him directly with Maclean, and the two men had not met for several years. MI5 decided not to arrest Maclean straight away. The Venona material was too secret to be used in court and so it was decided to keep Maclean under surveillance in the hope of gathering further evidence, for example, catching him in direct contact with his Soviet controller. Philby relayed the news to Moscow and demanded that Maclean be extracted from the UK before he was interrogated and compromised the entire British spy network.

Philby made the decision to use Guy Burgess to warn Maclean that he must flee to Moscow. The two men dined in a Chinese restaurant in downtown Washington, selected because it had individual booths with piped music, to prevent any eavesdroppers. Burgess said he would return to London in order to receive details of the escape plan. Before he left Philby made Burgess promise he would not flee with Maclean to Moscow: "Don't go with him when he goes. If you do, that'll be the end of me. Swear that you won't." Philby was aware that if Burgess went with Maclean, he would be suspected as a member of the network. (23)

He arrived back in England on 7th May 1951, and immediately contacted Anthony Blunt, who got a message to Yuri Modin, the Soviet controller of the Philby network. Blunt told Modin: "There's serious trouble, Guy Burgess has just arrived back in London. Homer's about to be arrested... It's only a question of days now, maybe hours... Donald's now in such a state that I'm convinced he'll break down the moment they arrest him." (24)

After receiving instructions from his superiors, Modin arranged for Maclean to escape to the Soviet Union. Modin was informed that Maclean would be arrested on 28th May. The plan was for Maclean to be interviewed by the Foreign Secretary, Herbert Morrison. "It has been assumed that Morrison held a meeting and that someone present at that meeting tipped off Burgess." (25) Another possibility is that a senior figure in MI5 was a Soviet spy, and he told Modin of the plan to arrest Maclean. This is the view of Peter Wright who suspects it was Roger Hollis who provided Modin with the information. (26)

On 25th May 1951, Burgess appeared at the Maclean's home in Tatsfield with a rented car, packed bags and two round-trip tickets booked in false names for the Falaise, a pleasure boat leaving that night for St Malo in France. Modin had insisted that Burgess must accompany Maclean. He later explained: "The Centre had concluded that we had not one, but two burnt-out agents on our hands on our hands. Burgess had lost most of his former value to us... Even if he retained his job, he could never again feed intelligence to the KGB as he had done before. He was finished." (27)

Maclean and Burgess took a train to Paris, and then another train to Berne in Switzerland. They then picked up fake passports in false names from the Soviet embassy. They then took another train to Zurich, where they boarded a plan bound for Stockholm, with a stopover in Prague. They left the airport and now safely behind the Iron Curtain, they were taken by car to Moscow. (28)

Melinda Maclean informed the Foreign Office on Monday, 28th May 1951, that her husband had gone missing. It was soon discovered that Burgess had also gone missing. The Foreign Office sent out an urgent telegram to embassies and MI6 stations throughout Europe, with instructions that Burgess and Maclean be apprehended "at all costs and by all means". A Missing Persons poster gave a description of the fugitives: "Maclean: 6 feet 3 inches, normal build, short hair, brushed back, part on left side, slight stoop, thin tight lips, long thin legs, sloppy dressed, chain smoker, heavy drinker. Burgess: 5 feet 9 inches, slender build, dark complexion, dark curly hair, tinged with grey, chubby face, clean shaven, slightly pigeon-toed." (29)

On his arrival in the Soviet Union Donald Maclean issued a statement: "I am haunted and burdened by what I know of official secrets, especially by the content of high-level Anglo-American conversations. The British Government, whom I have served, have betrayed the realm to Americans ... I wish to enable my beloved country to escape from the snare which faithless politicians have set ... I have decided that I can discharge my duty to my country only through prompt disclosure of this material to Stalin." (30)

Maclean was joined by his wife and his children in 1953. Maclean became a Soviet citizen and worked for the Foreign Ministry and the Institute of World Economic and International Relations. In 1970 Maclean published British Policy Since Suez. By 1979 his former wife and children had left and gone to the West. (31)

Donald Maclean died in Moscow on 6th March 1983.

Primary Sources

(1) Leonard Forster, interviwed by Andrew Boyle for his book The Climate of Treason (1979)

I knew Donald Madean quite well during our first year (at university). We went to the same supervisor and often compared notes about our work. I found him a very flabby character, naive about many things yet also unwilling to budge even when proved wrong or ridiculous. I didn't like his immaturity. He read a good deal, seldom laughed because he was very earnest, and had no marked sense of humour.

(2) Cyril Connolly knew Donald Maclean at Cambridge University . He wrote about him in The Missing Diplomats (1952)

Donald Maclean was sandy-haired, tall, with great latent physical strength, but fat and rather flabby. Meeting him, one was conscious of both amiability and weakness. He did not seem a political animal but resembled the clever, helpless youth in a Huxley novel, an outsize Cherubino intent on amorous experience but too shy and clumsy to succeed. The shadow of an august atmosphere lay heavy on him and he sought escape on the more impetuous and emancipated fringes of Bloomsbury and Chelsea.

What was common to both Burgess and Maclean at this time was their instability: both were able and ambitious young men of high intelligence and good connections who were somehow parodies of what they set out to be. Nobody could take them quite seriously: they were two characters in a late Russian novel.

(3) Cyril Connolly met Donald Maclean again during the Spanish Civil War. He wrote about him in The Missing Diplomats (1952)

A strong supporter of the Spanish Republic, Maclean seemed suddenly to have acquired a backbone, morally and physically. I remember some arguments with him. I had felt a strong sympathy for the Spanish anarchists, with whom he was extremely severe, as with other non-Communist factions, and I detected in his reproaches the familiar priggish tone of the Marxist, the resonance of the 'Father Found'. At the same time he could switch to a magisterial defence of Chamberlain's foreign policy and seemed able to hold the two self-righteous points of view simultaneously.

(4) Malcolm Muggeridge, interviwed by Andrew Boyle for his book The Climate of Treason (1979)

There's no doubt that Maclean knew his stuff. I found him a dull, humourless and rather pompous young man who tried a bit too hard to appear agreeable and relaxed. I can't say I ever warmed to Maclean. He was far too much of a cold fish beneath the polished surface charm. Nevertheless, during a bad period when the Americans were obviously determined to carry on in their own semi-isolationist way - Cold War or no Cold War - I couldn't but admire Maclean's astute appreciation of day-to-day diplomatic difficulties. He never struck a wrong note in public. He never lowered his guard.

(5) When Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean fled to the Soviet Union in 1951 Kim Philby was interviewed by Dick White. Philby wrote about the interview in his book, My Secret War (1968)

Taking the line that it was almost inconceivable that anyone like Burgess, who courted the limelight instead of avoiding it, and was generally notorious for indiscretion, could have been a secret agent, let alone a Soviet agent from whom strictest security standards would be required. I did not expect this line to be in any way convincing as to the facts of the case; but I hoped it would give the impression that I was implicitly defending myself against the unspoken charge that I, a trained counter-espionage officer, had been completely fooled by Burgess. Of Maclean, I disclaimed all knowledge.... As I had only met him twice, for about half an hour in all and both times on a conspiratorial basis, since 1937, I felt that I could safely indulge in this slight distortion of the truth.

(6) Herbert Morrison, An Autobiography (1960)

The security authorities were, of course, aware of leakage of information from the Foreign Office to the Soviet Government. They knew of this in January, 1949, but the information was so vague that it could not be traced to any individual. Highly secret investigations at a level which would be over the head of the Foreign Secretary and known only to the Prime Minister had begun, and by mid-April, when I had been Foreign Secretary for a month, the suspicion was focused on two or three officials. A fortnight later Maclean was regarded as the principal suspect, and on 25 May I sanctioned a proposal that Maclean should be questioned. Within a few hours Maclean, accompanied by Burgess, was making for France.

The coincidence was an alarming one, and at first suggested that there must have been some leakage in the security organization in that the sanction for questioning was known only to its personnel, myself and one or two very high officers of the Foreign Office, with no one else in the Foreign Office being involved. Possibly, however, it was a coincidence. Maclean could have noticed that he was no longer receiving as many secret papers as previously or the observation on his movements may have been detected by him.

Maclean's record of service had been satisfactory from 1935 until 1950, when he was guilty of bad conduct in Cairo, this being put down to overwork and excessive drinking. His subsequent appointment to the American Department was a comparatively easy job, chosen as such for a convalescent man, and incidentally not one where dangerous secrets often came his way. His comparative unimportance was a reason why I never medium officially on business, though I had met him formally at a Foreign Office social gathering.

Sent to Washington, his behaviour both on a personal plane and as regards carelessness with confidential papers had resulted in the Ambassador requesting his removal. The personal records of the two men did not reach me until after their escape. They should have been fired at the time of their transgressions.

(7) Donald Maclean, statement (May, 1951)

I am haunted and burdened by what I know of official secrets, especially by the content of high-level Anglo-American conversations. The British Government, whom I have served, have betrayed the realm to Americans ... I wish to enable my beloved country to escape from the snare which faithless politicians have set ... I have decided that I can discharge my duty to my country only through prompt disclosure of this material to Stalin.

(8) Time Magazine (25th June, 1951)

The disappearance of British Diplomats Donald MacLean and Guy Burgess was still a mystery without solution. A "well-informed source" said that the pair crossed the Pyrenees from Spain into France last week, traveling under assumed names; tourists said they saw them hurrying into Italy from Switzerland by way of the Simplon Pass; some amateur sleuths were sure the two had doubled back on their own trail, were back in Britain and hiding. When a daughter was born to Mrs. MacLean last week and her husband failed to give any sign, police all but abandoned hope that he and Burgess were still in Western Europe. Their guess: the two were either dead or behind the Iron Curtain.

MacLean and Burgess had left London on May 25, were last definitely reported in Rennes, France, running to catch a train to Paris. MacLean was head of the Foreign Office's American section and both men had served in the British embassy in Washington; they had access to plenty of confidential information which the Russians would be glad to get. Last week, London's Whitehall buzzed with rumors that the British counter-espionage unit, M.I.-5, was putting all Foreign Service men through a new and tighter security check, looking for traces of Communist sympathies or of homosexuality.

British newspapers were also hot on the trail. To check some tales about Burgess' private life, London's Daily Express dispatched its Hollywood reporter to Friend Christopher Isherwood, novelist (Prater Violet) and onetime parlor pink. "Was he a Communist?" mused Isherwood. "Well, like the rest of us, he was very much in favor of the United Front and Red Spain and so forth ... It meant, don't you see, that we were pretty favorable towards Russia ... I mean, it went without saying. But as far as I know, Guy was never a card-carrying party member. I have the strongest personal reasons for not wanting to go to Russia and I should think Guy Burgess would have exactly the same sort of reasons. We both happen to have exactly the same sort of tastes, and they don't meet with the approval of the Soviets. In fact, I'm told they liquidate chaps with our views—rather beastly, don't you think?"

Most Britons were less casual about the case. It stabbed sharply into the vitals of British pride and security. "It is the same sort of wound," wrote the weekly Time & Tide in a soul-searching article last week, "as that caused in the U.S. by the opening phases of the Hiss-Chambers duel . . . What reality is there now in our English assurances, in whose subtlety and strength we have taken such quiet pride? . . . Here are no lately nationalized refugee scientists, no fly-by-night fanatics making somber rendezvous ... If there is a particle of truth in the sinister rumors and speculations which have been rife, what Mr. Hydes are masked by the agreeable Dr. Jekylls whom everybody knows and likes? . . . [What can] stem the infection which the enemy appears able to inject into the bloodstream of us all, so that brother looks sideways at brother, and the friend of thirty years, the guest at lunch party or weekend frolic, becomes a bad security risk?"

(8) George Blake, interviewed by Clem Cecil of The Times (14th May 2003)

He (Donald Maclean) never liked spying. Philby and Burgess were attracted to the adventure and the secrecy of belonging to a small group of people with inside knowledge and they enjoyed the small amount of danger. Maclean didn't like that, but he felt he should do it as that was how he was of most use.