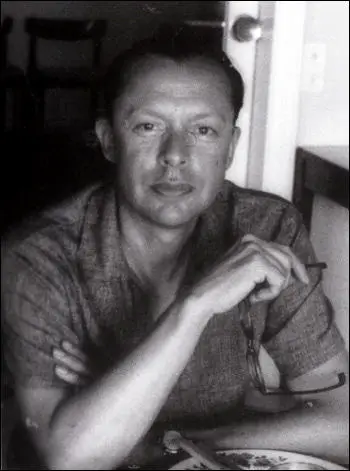

Nicholas Elliott

John Nicholas Elliott, the son of Claude Aurelius Elliott, who taught history at Cambridge University, was born in London on 15th November 1916.

His biographer, Ben Macintyre, argues that "Elliott was therefore brought up by a succession of nannies, and then shunted off to Durnford School in Dorset, a place with a tradition of brutality extreme even by the standards of British prep schools: every morning the boys were made to plunge naked into an unheated pool for the pleasure of the headmaster.... There was no fresh fruit, no toilets with doors, no restraint on bullying, and no possibility of escape." (1)

He was educated at Eton School and Trinity College. After leaving university he worked briefly in the Netherlands under Sir Neville Bland. (2) "There was no serious vetting procedure... Nevile simply told the Foreign Office that I was all right because he (Sir Neville Brand) knew me and had been at Eton with my father." (3)

In April 1939 Elliott visited Berlin and watched the celebrations taking place to celebrate the fiftieth birthday of Adolf Hitler. It included the largest military parade in the history of the Third Reich. Elliott was horrified by what he saw in Nazi Germany and returned to The Hague "with two new-minted convictions: that Hitler must be stopped at all costs and that the best way of contributing to that end would be to become a spy." (4)

Nicholas Elliott - MI6

During a visit to Ascot, Elliott was introduced to Sir Robert Vansittart, the permanent under-secretary at the Foreign Office. Vansittart shared Elliott's views on the danger of Hitler and was one of the most senior critics of the government's appeasement policy. Vansittart worked very closely with Admiral Hugh Sinclair, the head of MI6, and Vernon Kell, the head of MI5. According to Christopher Andrew, the author of The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009): "Robert Vansittart, permanent under secretary at the Foreign Office, was much more interested in intelligence than his political masters were... He dined regularly with Sinclair, was also in (less frequent) touch with Kell, and built up what became known as his own private detective agency collecting German intelligence. More than any other Whitehall mandarin, Vansittart stood for rearmament and opposition to appeasement." (5)

Vansittart arranged for Elliott to join MI6. One of his first jobs was to run Wolfgang zu Putlitz, First Secretary at the German Embassy and the journalist, Jona von Ustinov. Putlitz later recalled: "I would unburden myself of all the dirty schemes and secrets which I encountered as part of my daily routine at the Embassy. By this means I was able to lighten my conscience by the feeling that I was really helping to damage the Nazi cause for I knew Ustinov was in touch with Vansittart, who could use these facts to influence British policy." Putlitz insisted that the only way to deal with Adolf Hitler was to stand firm. (6)

On the outbreak of the Second World War he was commissioned in the Intelligence Corps. He was posted to Cairo in 1942, and was later based in Istanbul. His main task was to monitor anti-British activity. He married Elizabeth Holberton in 1943. The following year he joined forces with Kim Philby to help an important German intelligence officer, Erich Vermehren, to defect to Britain. Elliott described Vermehren as "a highly strung, cultivated, self-confident, extremely clever, logical-minded, slightly precious young German of good family", who was "intensely anti-Nazi on religious grounds". (7) This action "dealt a devastating blow to the effectiveness" of the Abwehr. (8) In 1945 Nicholas Elliott he was appointed as Head of Station in Berne.

Kim Philby - Investigated

When Donald Maclean defected in 1951 Philby became the chief suspect as the man who had tipped him off that he was being investigated. The main evidence against him was his friendship with Guy Burgess, who had gone with Maclean to Moscow. Philby was recalled to London. CIA chief, Walter Bedell Smith ordered any officers with knowledge of Philby and Burgess to submit reports on the men. William K. Harvey replied that after studying all the evidence he was convinced that "Philby was a Soviet spy". (9)

James Jesus Angleton reacted in a completely different way. In Angleton's estimation, Philby was no traitor, but an honest and brilliant man who had been cruelly duped by Burgess. According to Tom Mangold, "Angleton... remained convinced that his British friend would be cleared of suspicion" and warned Bedell Smith that if the CIA started making unsubstantiated charges of treachery against a senior MI6 officer this would seriously damage Anglo-American relations, since Philby was "held in high esteem" in London. (10)

On 12th June, 1951, Kim Philby was interviewed by Dick White, the chief of MI5 counter-intelligence. Philby later recalled: "He (White) wanted my help, he said, in clearing up this appalling Burgess-Maclean affair. I gave him a lot of information about Burgess's past and impressions of his personality; taking the line that it was almost inconceivable that anyone like Burgess, who courted the limelight instead of avoiding it, and was generally notorious for indiscretion, could have been a secret agent, let alone a Soviet agent from whom strictest security standards would be required. I did not expect this line to be in any way convincing as to the facts of the case; but I hoped it would give the impression that I was implicitly defending myself against the unspoken charge that I, a trained counter-espionage officer, had been completely fooled by Burgess. Of Maclean, I disclaimed all knowledge.... As I had only met him twice, for about half an hour in all and both times on a conspiratorial basis, since 1937, I felt that I could safely indulge in this slight distortion of the truth." (11)

White told Guy Liddell that he did not find Philby "wholly convincing". Liddell also discussed the matter with Philby and described him in his diary as "extremely worried". Liddell had known Guy Burgess for many years and was shocked by the news he was a Soviet spy. He now considered it possible that Philby was also a spy. "While all the points against him are capable of another explanation their cumulative effect is certainly impressive." Liddell also thought about the possibility that another friend, Anthony Blunt, was part of the network: "I dined with Anthony Blunt. I feel certain that Blunt was never a conscious collaborator with Burgess in any activities that he may have conducted on behalf of the Comintern." (12)

Nicholas Elliott was one friend who remained convinced that Philby was not a spy. "Elliott was wholeheartedly, unwaveringly convinced of Philby's innocence. They had joined MI6 together, watched cricket together, dined and drunk together. It was simply inconceivable to Elliott that Philby could be a Soviet spy. The Philby he knew never discussed politics. In more than a decade of close friendship, he had never heard Philby utter a word that might be considered left-wing, let alone communist. Philby might have made a mistake, associating with a man like burgess; he might have dabbled in radical politics at university; he might even have married a communist, and concealed the fact. But these were errors, not crimes." (13)

CIA chief, Walter Bedell Smith, had been convinced by the report produced by William K. Harvey and wrote directly to Stewart Menzies, the head of MI6, and made it clear that he considered that Philby was a Soviet spy and would not be permitted to return to Washington and urged the British government to "clean house regardless of whom may be hurt". Burton Hersh, the author of The Old Boys: The American Elite and the Origins of the CIA (1992), has claimed that the underlying message was blunt: "Fire Philby or we break off the intelligence relationship." (14) Dick White also wrote to Menzies suggesting that MI6 take action as a matter of urgency.

Menzies refused to believe Philby was a Soviet spy but realised he would have to dismiss him. He agreed to give him a generous payoff, £4,000, equivalent to more than £32,000 today. Philby was not happy with the settlement: "My unease was increased shortly afterwards when he told me that he had decided against paying me the whole sum at once. I would get £2,000 down and the rest in half-yearly instalments of £500." (15) Nicholas Elliott still continued to support Philby and argued that he had been treated very badly and believed that a "dedicated, loyal officer had been treated abominably on the basis of evidence that there was no more than paranoid conspiracy theory." (16)

Buster Crabb

In 1953 he was transferred to Vienna before returning in 1956 to London, where he was responsible for all home-based operations. John le Carré met him during this period: "Nicholas Elliott of M16 was the most charming, witty, elegant, courteous, compulsively entertaining spy I ever met. In retrospect, he also remains the most enigmatic.To describe his appearance is, these days, to invite ridicule. He was a bon viveur of the old school. I never once saw him in anything but an immaculately cut, dark three-piece suit. He had perfect Etonian manners, and delighted in human relationships. He was thin as a wand, and seemed always to hover slightly above the ground at a jaunty angle, a quiet smile on his face and one elbow cocked for the Martini glass or cigarette." (17)

In April 1956, the Soviet leaders, Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin paid a visit on the battleship Ordzhonikidz, docking at Portsmouth. The visit was designed to improve Anglo-Soviet relations. Sir Anthony Eden, the prime minister, who had high hopes of establishing better relations and moderating the Cold War issued a precise directive to all services banning any intelligence operation of any kind against the Soviet leaders and the ship. (18)

Elliott decided that the visit was too good an opportunity to miss and ten days beforehand put up a list of six operations to MI6's Foreign Office adviser. "The Admiralty had been particularly keen to understand the underwater-noise characteristics of the Soviet vessels. The placing of a Foreign Office adviser inside MI6 was part of a drive to put the service on a somewhat tighter leash, but when an MI6 officer ambled into his office for a ten-minute chat about the plans, the adviser came away thinking they would then be cleared at a higher level (as some sensitive operations were) while Elliott and his colleagues assumed that the quick conversation constituted clearance." (19) When Eden heard about it he told MI6: "I am sorry, but we cannot do anything of this kind on this occasion." Elliott would later insist that the "operation was mounted after receiving a written assurance of the Navy's interest and in the firm belief that government clearance had been given". (20) Elliott also argued: "We don't have a chain of command. We work like a club." (21)

On 16th April 1956, the day before the cruiser was due to arrive, Buster Crabb and Bernard Smith, his MI6 minder, arrived in Portsmouth and registered with a local hotel. Against the rules of the SIS both men signed in their real names. Contrary to the fundamental rules of diving, that evening Crabb drank at least five double whiskys. By daybreak, the toxicity in his blood remained fatally high. (22)

The following morning Crabb dived into Portsmouth Harbour. "The main task was to swim underneath the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze, explore and photograph her keel, propellers and rudder, and then return. It would be a long, cold swim, alone, in extremely cold and dirty water, with almost zero visibility at a depth of about thirty feet. The job might have daunted a much younger and healthier man. For a forty seven-year-old, unfit, chain-smoking depressive, who had been extremely drunk a few hours earlier, it was close to suicidal." (23) However, Elliott insisted that "Crabb was still the most experienced frogman in England, and totally trustworthy ... He begged to do the job for patriotic as well as personal motives." (24) Peter Wright, who worked for MI5 said that it was a typical piece of MI6 adventurism, ill-conceived and badly executed." (25)

Gordon Corera, the author of The Art of Betrayal (2011) has pointed out: "Where Bond battled the bad guys in the crystal-clear Caribbean, the diminutive Crabb plunged into the cold, muddy tide of Portsmouth Harbour just before seven in the morning. He had about ninety minutes of air and by 9.15 it was clear something had gone wrong. For a while, it looked like the whole affair might be hushed up. The MI6 officer went back to the hotel to rip out the registration page. The hotel owner went to the press, who sniffed a good story. The disappearance of a well-known hero could not be covered up." (26)

That night, James Thomas, the First Lord of the Admiralty, was dining with some of the Soviet visitors, one of whom asked, "What was that frogman doing off our bows this morning". According to the Russian, Crabb had been seen swimming at the surface at 7.30 a.m. by a Soviet sailor. (27) The commander-in-chief Portsmouth, denying knowledge of any frogman, assured the Russian there would be an Inquiry and hoped that all discussion had been terminated. With the help of the intelligence services, the Admiralty attempted to cover up the attempt to spy on the Russian ship. On 29th April the Admiralty announced that Crabb went missing after taking part in trials of underwater apparatus in Stokes Bay (a place five kilometres from Portsmouth).

The Soviet government now issued a statement announcing that a frogman was seen near the cruiser Ordzhonikidze on 19th April. This resulted in newspapers publishing stories claiming that Buster Crabb had been captured and taken to the Soviet Union. Time Magazine reported: "... soon after anchoring, the Ordzhonikidze had taken the precaution of putting a crew of its own frogmen over the side. Had the Russian frogmen met their British counterpart in the quiet deep? Had Buster Crabb been killed then and there, or kidnapped and carried off to Russia? At week's end, the mystery of Frogman Crabb's fate remained as deep and impenetrable as the waters that surrounded so much of his life." (28) Nicholas Elliott claimed that he knew how Crabb died: "He almost certainly died of respiratory trouble, being a heavy smoker and not in the best of health, or conceivably because some fault had developed in his equipment." (29)

Sir Anthony Eden, the British prime minister was furious when he discovered about the MI6 operation that had taken place without his permission. Eden pointed out in the House of Commons: "I think it is necessary, in the special circumstances of this case, to make it clear that what was done was done without the authority or knowledge of Her Majesty's Ministers. Appropriate disciplinary steps are being taken." (30) Ten days later, Eden made another statement making it clear that his explicit instructions had been disobeyed. (31)

Eden forced the Diretor-General of MI6, Major-General John Sinclair, to take early retirement. He was replaced by Sir Dick White, the head of MI5. As MI5 was considered by MI6 to be an inferior intelligence service, this was the severest punishment that could be inflicted on the organization. George Kennedy Young, a senior figure in MI6 defended the actions of Elliott. He argued that in "a world of increasing lawlessness, cruelty and corruption... it is the spy who has been called upon to remedy the situation created by the deficiencies of ministers, diplomats, generals and priests.. these days the spy finds himself the main guardian of intellectual integrity." (32)

Kim Philby

In 1956 Nicholas Elliott arranged for Kim Philby to work for MI6 in Beirut. His cover was as a journalist being employed by the Observer and the Economist: "The Observer and Economist would share Philby's services, and pay him £3,000 a year plus travel and expenses. At the same time, Elliott arranged that Philby would resume working for MI6, no longer as an officer, but as an agent, gathering information for British intelligence in one of the world's most sensitive areas. He would be paid a retainer through Godfrey Paulson, chief of the Beirut MI6 station." (33)

Yuri Modin later pointed out that Philby provided some very important information to the Soviet Union. "Philby was by no means our only asset in the Middle East, and the KGB had its own experts here in Moscow and in the capitals, highly trained Arabists all. But I can say that Philby sent us excellent results that attracted much attention at the top, although occasionally there was criticism of him concerning his tendency to send us hard news wrapped up in beautifully-written political evaluations. We did not need this because we had our own people to make evaluations. What we needed from Philby was not his views but his news. But in all he served as well." (34)

In 1960 Nicholas Elliott became Head of Station in Beirut. With the Middle East becoming a source of political tension the posting was considered to be a "step up in the intelligence ladder". Patrick Seale, a journalist who met him during this period later described him as a much respected figure in MI6: "He was a thin, spare man with a reputation as a shrewd operator whose quick humorous glance behind round glasses gave a clue to his sardonic mind. In manner and dress he suggested an Oxbridge don at one of the smarter colleges, but with a touch of worldly ruthlessness not always evident in academic life. Foreigners liked him, appreciating his bonhomie and his fund of risque stories. He got on particularly well with Americans. The formal, ladylike figure of his wife in the background contributed to the feeling that British intelligence in Beirut was being directed by a gentleman." (35)

Kim Philby's Confession

Armed with information from Anatoli Golitsin and Flora Solomon, both Dick White for MI6 and Roger Hollis of MI5 agreed that Philby should be interrogated again. Initially they selected Arthur Martin for the task. As Peter Wright has pointed out: "He (Arthur Martin) had pursued the Philby case from its beginning in 1951, and knew more about it than anyone." However, at the last moment they changed their mind. Elliott was in London as he had just been appointed as the MI6 director for Africa. It was decided to send Elliott instead. "Elliott was now convinced of Philby's guilt, and it was felt he could better play on Philby's sense of decency. The few of us inside MI5 privy to this decision were appalled... We in MI5 had never doubted Philby's guilt from the beginning, and now at last we had the evidence we needed to corner him. Philby's friends in MI6, Elliott chief among them, had continually protested his innocence. Now, when the proof was inescapable, they wanted to keep it in-house. The choice of Elliott rankled strongly as well. He was the son of the former headmaster of Eton and had a languid upper-class manner." (36)

Elliott flew out from London at the beginning of 1963 to confront Philby in Beirut. According to Philby's later version of events given to the KGB after he escaped to Moscow, Elliott told him: "You stopped working for them (the Russians) in 1949, I'm absolutely certain of that... I can understand people who worked for the Soviet Union, say before or during the war. But by 1949 a man of your intellect and your spirit had to see that all the rumours about Stalin's monstrous behaviour were not rumours, they were the truth... You decided to break with the USSR... Therefore I can give you my word and that of Dick White that you will get full immunity, you will be pardoned, but only if you tell it yourself. We need your collaboration, your help." (37)

Arthur Martin, head of the Soviet counter-espionage section, and Peter Wright spent a great deal listening to the confession that Kim Philby had made to Nicholas Elliott. Wright later argued: "There was no doubt in anyone's mind, listening to the tape, that Philby arrived at the safe house well prepared for Elliott's confrontation. Elliott told him there was new evidence, that he was now convinced of his guilt, and Philby, who had denied everything time and again for a decade, swiftly admitted spying since 1934. He never once asked what the new evidence was." Both men came to the conclusion that Philby had not asked about the new evidence as he had already been told about it. This convinced them that the "Russians still had access to a source inside British Intelligence who was monitoring the progress of the Philby case. Only a handful of officers had such access, chief among them being Hollis and Mitchell." (38)

Elliott told Philby: "I can give you my word, and that of Dick White, that you will get full immunity; you will be pardoned, but only if you tell it yourself. We need your collaboration, your help." Philby still refused to confess. Elliott then threatened him with having his passport taken away and his residence permit revoked. He would not be able to to open a bank account. He would be prevented from working as a journalist. "If you cooperate, we will give you immunity from prosecution. Nothing will be published." Philby was given 24 hours to make a decision. (39)

According to Philby's later version of events given to the KGB after he escaped to Moscow, Elliott told him: "You stopped working for them (the Russians) in 1949, I'm absolutely certain of that... I can understand people who worked for the Soviet Union, say before or during the war. But by 1949 a man of your intellect and your spirit had to see that all the rumours about Stalin's monstrous behaviour were not rumours, they were the truth... You decided to break with the USSR... Therefore I can give you my word and that of Dick White that you will get full immunity, you will be pardoned, but only if you tell it yourself. We need your collaboration, your help." (40)

Kim Philby did provide a two-page summary of his spying activities but it included several inaccuracies. He claimed he had been recruited by his first wife, Litzi Friedmann, in 1934. He then recruited Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess. Philby lied when he said he had "seen the error of his ways" and stopped spying for the Soviet Union in 1945. He admitted that he had tipped off Maclean in 1951 as "an act of loyalty to a friend" and not as one active spy protecting another. Philby gave a list of the codenames of his early Soviet handlers but made no reference to those he worked with after the war. (41)

Elliott told him that this was not enough: "Our promise of immunity and pardon depends wholly on whether you give us all the information that you have. First of all we need information on people who worked with Moscow. By the way we know them." (42) Elliott was lying about this but of course Philby did not know how much information MI6 had about his activities. For example, he did not know if another member of the network had confessed. Peter Wright, who later listened to the tapes, commented that "by the end, they sounded like two rather tipsy radio announcers, their warm, classical public school accents discussing the greatest treachery of the twentieth century." (43)

The following day Elliott had another meeting with Philby. Elliott gave him a list of around twelve names who MI6 suspected of being spies. This included Anthony Blunt, Tomás Harris, John Cairncross, Guy Liddell and Tim Milne. Philby later told Phillip Knightley that there were several names on the list "which alarmed me". (44) However, he only named one person, Milne, as a spy. In fact, he was the only name on the list who was completely innocent.

After four days of interrogation Elliott told Philby that he was travelling on to the Congo and that another officer, Peter Lunn, would take over the debriefing process in Beirut. The head of MI5, Roger Hollis, sent a memo to J. Edgar Hoover: "In our judgement Philby's statement of the association with the RIS (Russian Intelligence Service) is substantially true. It accords with all the available evidence in our possession and we have no evidence pointing to a continuation of his activities on behalf of the RIS after 1946, save in the isolated instance of Maclean. If this is so, it follows that damage to United States interests will have been confined to the period of the Second World War." (45)

Kim Philby in Moscow

Kim Philby was now aware that he was in danger of being arrested and therefore on 23rd January, 1963, Kim Philby fled to Moscow. Nicholas Elliott later claimed that he and MI6 were surprised by the defection. "It just didn't dawn on us." (46) Ben Macintyre, the author of A Spy Among Friends (2014) argues: "This defies belief. Burgess and Maclean had both defected... Philby knew he now faced sustained interrogation, over a long period, at the hands of Peter Lunn, a man he found unsympathetic. Elliott had made it quite clear that if he failed to cooperate fully, the immunity deal was off and the confession he had already signed would be used against him... There is another, very different way to read Elliott's actions. The prospect of prosecuting Philby in Britain was anathema to the intelligence services; another trial, so soon after the Blake fiasco, would be politically damaging and profoundly embarrassing." (47)

Desmond Bristow, MI6's head of station in Spain, agreed with this analysis: "Philby was allowed to escape. Perhaps he was even encouraged. To have him brought back to England and convicted as a traitor would have been even more embarrassing; and when they convicted him, could they really have hanged him?" (48) Yuri Modin, who was the man the KGB selected to talk to Philby before he defected, also believes this was the case: "To my mind the whole business was politically engineered. The British government had nothing to gain by prosecuting Philby. A major trial, to the inevitable accompaniment of spectacular revelation and scandal, would have shaken the British establishment to its foundations." (49)

Kim Philby was giving a luxury flat in Moscow and given a salary of £200 a month. Eleanor Philby joined Philby in the Soviet Union on 26th September 1963. A few weeks later Philby wrote to Nicholas Elliott: "I am more than thankful for your friendly interventions at all times. I would have got in touch with you earlier, but I thought it better to let time do its work on the case. It is invariably with pleasure that I remember our meetings and talks. They did much to help one get one's bearings in this complicated world! I deeply appreciate, now as ever, our old friendship, and I hope that rumours which have reached me about your having had some trouble on my account, are exaggerated. It would be bitter to feel that I might have been a source of trouble to you, but I am buoyed up by my confidence that you will have found a way out of any difficulties that may have beset you." (50) Philby suggested the two men should meet in East Berlin. Elliott wanted to go but Dick White rejected the idea.

Retirement

Nicholas Elliott retired from MI6 in 1968. "Rather to my surprise I did not miss the confidential knowledge which no longer filtered through my in-tray." (51) He joined the board of Lonrho, the international mining and media company, and became executive director of the company in 1969. He left in 1973 with several colleagues, after a failed attempt to remove Tiny Rowland, the head of the company.

In 1986 Nicholas Elliott resumed his friendship with John le Carré, who was now a famous novelist. "After a turbulent spell in the City, Elliott in the most civilised of ways seemed a bit lost. He was also deeply frustrated by our former Service's refusal to let him reveal secrets which in his opinion had long passed their keep-till date. He believed he had a right, even a duty, to speak truth to history. And perhaps that's where he thought I might come in - as some sort of go-between or cut out, as the spies would have it, who would help him get his story into the open where it belonged."

John le Carré claimed that Elliott mainly wanted to talk about Kim Philby: "And so it happened, one evening in May 1986 in my house in Hampstead, twenty-three years after he had sat down with Philby in Beirut and listened to his partial confession, that Nicholas Elliott opened his heart to me in what turned out to be the first in a succession of such meetings.... And it quickly became clear that he wanted to draw me in, to make me marvel, as he himself marvelled; to make me share his awe and frustration at the enormity of what had been done to him; and to feel, if I could, or at least imagine, the outrage and the pain that his refined breeding and good manners - let alone the restrictions of the Official Secrets Act - obliged him to conceal.... Like Philby, Elliott never spoke a word out of turn, however much he drank: except of course to Philby himself. Like Philby, he was a five-star entertainer, always a step ahead of you, bold, raunchy, and funny as hell. Yet I don't believe I ever seriously doubted that what I was hearing from Elliott was the cover story - the self-justification - of an old and outraged spy." (52)

Kim Philby lived in the Soviet Union until his death on 11th May 1988. He was given a grand funeral with a KGB honour guard and in his official obituary was lauded for his "tireless struggle in the cause of peace and a brighter future. (53) Nicholas Elliott recommended to MI6 that Philby should be awarded the CMG, the order of St Michael and St George, the sixth most prestigious award in the British honours system, awarded to men and women who render extraordinary or important non-military service in a foreign country." Elliott suggested that he should write an obituary saying: "My lips have hitherto been sealed but I can now reveal that Philby was one of the bravest men I have ever known." The intention was to suggest that Philby was not a valiant Soviet double agent, but a heroic British triple agent. However, MI6 turned the idea down. Maybe because they believed that the British public would no longer be fooled by old-style deception operations. (54)

Elliott became an unofficial adviser on intelligence matters to Margaret Thatcher. He also wrote two volumes of autobiography, Never Judge a Man by His Umbrella (1991) and With My Little Eye: Observations Along the Way (1994).

Nicholas Elliott died in London on 13th April 1994.

Primary Sources

(1) Ben Macintyre, A Spy Among Friends (2014)

Elliott could never recall exactly where their first meeting took place. Was it the bar in the heart of the MI6 building on Broadway, the most secret drinking hole in the world? Or perhaps it was at White's, Elliott's club. Or the Athenaeum, which was Philby's. Perhaps Philby's future wife, Aileen, a distant cousin of Elliott's, brought them together. It was inevitable that they would meet eventually, for they were creatures of the same world, thrown together in important clandestine work, and remarkably alike, in both background and temperament. Claude Elliott and Philby's father St John, a noted Arab scholar, explorer and writer, had been contemporaries and friends at Trinity College, and both sons had obediently followed in their academic footsteps - Philby, four years older, left Cambridge the year Elliott arrived. Both lived under the shadow of imposing but distant fathers, whose approval they longed for and never quite won. Both were children of the Empire: Kim Philby was born in the Punjab where his father was a colonial administrator; his mother was the daughter of a British official in the Raiwalhindi Public Works Department. Elliott's father had been born in Simla. Both had been brought up largely by nannies, and both were unmistakably moulded by their schooling: Elliott wore his Old Etonian tie with pride; Philby cherished his Westminster School scarf. And both concealed a certain shyness, Philby behind his impenetrable charm and fluctuating stammer, and Elliott with a barrage of jokes.

They struck up a friendship at once. "In those days," wrote Elliott, "friendships were formed more quickly than in peacetime, particularly amongst those involved in confidential work." While Elliott helped to intercept enemy spies sent to Britain, Philby was preparing Allied saboteurs for insertion into occupied Europe.They found they had much to talk and joke about, within the snug confines of absolute secrecy.

(2) Patrick Seale & Maureen McConville, Philby: The Long Road to Moscow (1973)

He was a thin, spare man with a reputation as a shrewd operator whose quick humorous glance behind round glasses gave a clue to his sardonic mind. In manner and dress he suggested an Oxbridge don at one of the smarter colleges, but with a touch of worldly ruthlessness not always evident in academic life. Foreigners liked him, appreciating his bonhomie and his fund of risque stories. He got on particularly well with Americans. The formal, ladylike figure of his wife in the background contributed to the feeling that British intelligence in Beirut was being directed by a gentleman.

(3) Peter Wright, Spycatcher (1987)

Armed with Golitsin's and Solomon's information, both Dick White for MI6 and Roger Hollis agreed that Philby should be interrogated again out in Beirut. From August 1962 until the end of the year, Evelyn McBarnet drew up a voluminous brief in preparation for the confrontation. But at the last minute there was a change of plan. Arthur was originally scheduled to go to Beirut. He had pursued the Philby case from its beginning in 1951, and knew more about it than anyone. But he was told that Nicholas Elliott, a close friend of Philby's, who had just returned from Beirut where he had been Station Chief, would go instead. Elliott was now convinced of Philby's guilt, and it was felt he could better play on Philby's sense of decency. The few of us inside MI5 privy to this decision were appalled. It was not simply a matter of chauvinism, though, not unnaturally, that played a part. We in MI5 had never doubted Philby's guilt from the beginning, and now at last we had the evidence we needed to corner him. Philby's friends in MI6, Elliott chief among them, had continually protested his innocence. Now, when the proof was inescapable, they wanted to keep it in-house. The choice of Elliott rankled strongly as well. He was the son of the former headmaster of Eton and had a languid upper-class manner. But the decision was made, and in January 1963 Elliott flew out to Beirut, armed with a formal offer of immunity.

He returned a week later in triumph. Philby had confessed. He had admitted spying since 1934. He was thinking of coming back to Britain. He had even written out a confession. At last the long mystery was solved.

(4) John le Carré, Nicholas Elliott (2014)

Nicholas Elliott of M16 was the most charming, witty, elegant, courteous, compulsively entertaining spy I ever met. In retrospect, he also remains the most enigmatic.To describe his appearance is, these days, to invite ridicule. He was a bon viveur of the old school. I never once saw him in anything but an immaculately cut, dark three-piece suit. He had perfect Etonian manners, and delighted in human relationships.

He was thin as a wand, and seemed always to hover slightly above the ground at a jaunty angle, a quiet smile on his face and one elbow cocked for the Martini glass or cigarette.

His waistcoats curved inwards, never outwards. He looked like a P. G. Wodehouse man-about-town, and spoke like one, with the difference that his conversation was startlingly forthright, knowledgeable, and recklessly disrespectful of authority.

During my service in MI6, Elliott and I had been on nodding terms at most. When I was first interviewed for the Service, he was on the selection board.When I became a new entrant, he was a fifth-floor grandee whose most celebrated espionage coup - the wartime recruitment of a highly placed member of the German Abwehr in Istanbul, smuggling him and his wife to Britain - was held up to trainees as the ultimate example of what a resourceful field officer could achieve.

And he remained that same glamorous, remote figure throughout my service. Flitting elegantly in and out of head office, he would deliver a lecture, attend an operational conference, down a few glasses in the grandees' bar, and be gone.

I resigned from the Service at the age of thirty-three, having made a negligible contribution. Elliott resigned at the age of fifty-three, having been central to pretty well every major operation that the Service had undertaken since the outbreak of the Second World War.Years later, I bumped into him at a party.

After a turbulent spell in the City, Elliott in the most civilised of ways seemed a bit lost. He was also deeply frustrated by our former Service's refusal to let him reveal secrets which in his opinion had long passed their keep-till date. He believed he had a right, even a duty, to speak truth to history. And perhaps that's where he thought I might come in - as some sort of go-between or cut out, as the spies would have it, who would help him get his story into the open where it belonged.

Above all, he wanted to talk to me about his friend, colleague, and nemesis, Kim Philby.

And so it happened, one evening in May 1986 in my house in Hampstead, twenty-three years after he had sat down with Philby in Beirut and listened to his partial confession, that Nicholas Elliott opened his heart to me in what turned out to be the first in a succession of such meetings. Or if not his heart, a version of it.

And it quickly became clear that he wanted to draw me in, to make me marvel, as he himself marvelled; to make me share his awe and frustration at the enormity of what had been done to him; and to feel, if I could, or at least imagine, the outrage and the pain that his refined breeding and good manners - let alone the restrictions of the Official Secrets Act - obliged him to conceal.

Sometimes while he talked I scribbled in a notebook and he made no objection. Looking over my notes a quarter of a century later - twenty-eight pages from one sitting alone, handwritten on fading notepaper, a rusty staple at one corner - I am comforted that there is hardly a crossing out...

Like Philby, Elliott never spoke a word out of turn, however much he drank: except of course to Philby himself. Like Philby, he was a five-star entertainer, always a step ahead of you, bold, raunchy, and funny as hell. Yet I don't believe I ever seriously doubted that what I was hearing from Elliott was the cover story - the self-justification - of an old and outraged spy.

(5) Stephen Hastings, The Independent (18th April, 1984)

Nicholas Elliott was the son of Claude Aurelius Elliott, a don at Cambridge, who subsequently became a successful and popular Headmaster and Provost of Eton, whither Nicholas was sent after a fairly horrific experience at Durnford, a notoriously Spartan and uncomfortable preparatory school in Dorset. Apart from his other attainments at Eton, Nicholas developed a lifelong interest in racing and managed for a time to run a clandestine bookmaking business. This was, of course, against the rules and eventually led to confrontation with his father. After remonstrating, the Headmaster agreed to buy him out for so much per term. Doubtless this was useful practice for Elliott's subsequent career in MI6 and says a good deal for his negotiating powers. He had a strong bond with his father, who figures prominently in his first and most amusing memoir, Never Judge a Man by his Umbrella (1991).

After leaving Trinity College, Cambridge, Elliott was offered a post in 1938 as Honorary Attache at The Hague by Sir Neville Bland. His career in secret intelligence came by chance, like many before and after him. Sir Hugh Sinclair, Head of MI6, happened to visit The Hague, took to Elliott and offered him a job.

On the outbreak of the Second World War he was commissioned in the Intelligence Corps, posted to Cairo in 1942, and subsequently to Istanbul; a seething hive of wartime espionage. His job was to check anti-British activity and he became an extremely effective Field Officer, obtaining the defection of an important German intelligence officer, Dr Erich Vermehren, an operation which dealt a devastating blow to the effectiveness of the Abwehr in 1944.

After the war Elliott returned to Britain, whence he was posted to Berne in 1945 as Head of Station. In 1953 he was transferred to Vienna, again as Head of Station, returning in 1956 to London, where he was responsible for all home-based operations. From 1960 to 1962 he was in charge in Beirut, eventual scene of his famous confrontation with the traitor Kim Philby. Elliott also served in Israel, where the links he built with Mossad, the extremely effective Israeli intelligence service, played a vital part during the Suez crisis and later. Subsequently he served as a director of MI6 for several years before his retirement in 1969.

Elliott was above all an operational officer. Pen-pushing and detailed analysis behind a desk were not for him. Indeed he regarded the 'intellectuals' in the Service with some contempt. In his second memoir, With My Little Eye (1994), he describes the qualities he believed necessary to succeed in this tense and exacting profession: "The successful Field Officers will be generally found to have three important characteristics. They will be personalities in their own right. They will have humanity and a capacity for friendship and they will have a sense of humour which will enable them to avoid the ridiculous mumbo-jumbo of over-secrecy." The cap fits Elliott well.

His was a distinguished career, publicly and unluckily marked by two notorious events, the death of Commander Lionel Crabb and the flight of Kim Philby to Moscow. Elliott and the Service suffered criticism in both cases and he felt this deeply to the end of his life.

In 1956, during Khrushchev's visit to Britain, the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze lay in Portsmouth harbour. The Navy was vitally interested in certain equipment carried under the stern. Elliott arranged for Crabb, an experienced ex-naval frogman, to investigate. He made one successful run under the ship, came back for an extra pound of weight for his next attempt and never returned. It seems probable that Crabb was no longer fit enough or it could be that his equipment failed.

There is not the slightest reason to doubt Elliott's account of what happened (in With My Little Eye) and he deeply resented subsequent criticism of Crabb, whom he knew as a brave and honourable officer and a holder of the George Medal, who had undertaken successful operations of this kind before.

The Russians, who had reported a diver in trouble near the stern, were in no way discountenanced, did not complain, and were not responsible for Crabb's death. In any case, they regard espionage as an inevitable extension of international relations. But by mischance the matter leaked. Anthony Eden protested he had not been informed and thus ensured the maximum adverse publicity. Elliott had been given every reason to believe the operation had been cleared by the Foreign Office.

Later in With My Little Eye Elliott gives a clear account of his last contacts with Kim Philby, in 1963. Philby had been a friend and Elliott felt his betrayal bitterly. Typically he volunteered to confront the traitor himself. He was instructed to go to Beirut, where he obtained Philby's written confession. After Elliott returned to London, Philby fled to Moscow in circumstances calculated to cause the maximum pain to his family. When the news of his escape broke, public reaction was predictably critical. Perhaps matters might have been handled otherwise but this was scarcely Elliott's fault. He had done what he was told to do and it is difficult to see how he could possibly have prevented Philby's escape.