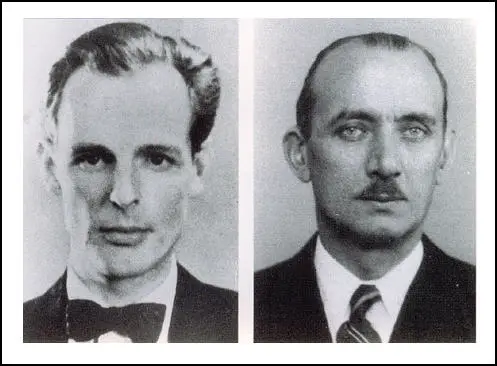

John Herbert King

John Herbert King was born in 1884. King joined the Artists' Rifles during the First World War and went out to the Middle East where he became a cipher officer. After the war he joined the Foreign Office in a similar capacity. He was first posted to Paris, where he associated with Sidney Reilly, who at that time was working as an agent for MI6. In 1926 he was transferred to Berlin. It was about that time that he separated from his wife.

In 1934 he worked for the British Delegation to the League of Nations in Geneva. In 1935 he became a cypher clerk at the British Foreign Office. He began having financial problems and became a target of NKVD. According to Gary Kern he was approached by Henri Pieck: "Captain John Herbert King was a clerk without a pension or decent prospects for the future. Over beer with Pieck, he expressed himself as a disgruntled Irishman, a victim of English discrimination, under appreciated and underpaid. He had a son who deserved the best things in life and an American mistress whose tastes were not inexpensive. Pieck sympathized. He and his wife took King and his mistress on a paid vacation to Spain and made King hunger for the pleasures of high society."

in 1935 King became a Soviet spy by. His code-name was MAG. During the first year King routinely delivered a package after work to a photographic studio at 34 Buckingham Gate, not far from the Foreign Office in Whitehall, and picked it up on his way to work the next morning. The studio was rented by Pieck's business partner, Conrad Parlanti, who thought it had something to do with interior decorating. Donald Maclean (code-named WAISE) who joined the Foreign Office in October 1935, and became part of the same spy network. King was able to provide a verbatim account of a meeting that Lord Halifax had with Adolf Hitler in 1936. This was then passed on to Joseph Stalin. The man who oversaw the operation in Moscow was Dmitri Bystrolyotov. He recorded that "MAG works with clockwork precision."

In 1936 Henri Pieck developed security problems and King and Donald Maclean were passed on to Theodore Maly. Over the next few years he provided Foreign Office telegraphic traffic to the Russian Intelligence Service. On 24th May 1936, Maly reported: "Tonight WAISE (Maclean) arrived with an enormous bundle of dispatches, of which MAG (King) had supplied only a few. Only part of them have been photographed, which we have marked with a W, because we have run out of film and today is Sunday - and night-time at that. We wanted him (Maclean) to take out a military intelligence bulletin, but he did not succeed in doing this. On Saturday he must stay on duty in London and we hope that he will be able to bring out more, including those which he has not managed to get out yet."

Gary Kern, the author of A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004), claims that "King... supplied his handlers with thousands of classified documents, most of them very - fresh, including daily telegrams and weekly summaries of diplomatic communications, special materials from the safe of the cipher department, and personally generated observations, analyses and reports." King's handler, Maly was considered a security risk and he was recalled to Moscow in 1937 and executed. Arnold Deutsch now took over King.

Walter Krivitsky, the Chief of the Soviet Military Intelligence for Western Europe, defected to the United States as a result of the executions of his agents, Maly, Ignaz Reiss, Yan Berzin and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko. Krivitsky provided information to the journalist Isaac Don Levine, and on 5th August, 1939, he published an article in the Saturday Evening Post that Joseph Stalin had two agents working deep inside the British government. Lord Lothian, the British Ambassador to the United States, was told by Levine that one of the men was named King. He also gave him evidence that enabled him to identify Ernest Holloway Oldham, who had died in 1933.

On 4th September 1939, MI5 was informed that Krivitsky had told them that "King in the Foreign Office Communications Department" is "selling everything to Moscow". Richard Deacon, the author of A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972) has pointed out that "when he was arrested a top-secret message was found in his possession: he was on his way to a tea-shop in Whitehall to meet his Russian contact.... And this in itself is curious, for why did not the authorities follow him to the tea-shop and arrest his contact as well? That would have been normal procedure."

On 25th September, King was interviewed by Colonel Valentine Vivian, head of Section V (counter-espionage) in SIS. At first he refused to confess. Sir Alexander Cadogan, the Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs wrote in his diary on 26th September, "I have no doubt he is guilty - curse him - but there is no absolute proof." King eventually cracked and confessed to being a Soviet spy. Colonel Vivian suspected that there were other spies in the Communication Department but failed to find enough evidence for prosecution. Two officials, however, were dismissed for "irregularities". Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, gave orders for all existing members of the department to be moved to other jobs and bring in fresh staff.

King was tried in secret at the Old Bailey on 18th October 1939. He was found guilty and sentenced to ten years' imprisonment. Richard Deacon has argued: "The case of Captain King seems to have been curious in a number of ways. The trial was held in the No. 1 Court of the Old Bailey before Mr. Justice Hilbery in conditions of great secrecy. King was the first spy to be tried in Britain in World War II and the M.I.5 agents who trapped him went to the Old Bailey in a curtained car. All corridors were cleared. But though it is customary in wartime for such trials to be held in secret, normally the result and sentence are publicised. In the case of Captain King no details were published and everything was hushed up." Emil Draitser, claims that he was released early at the end of the Second World War in 1945.

Details of the case of John Herbert King was kept secret until the journalist, Isaac Don Levine, who had worked with Walter Krivitsky on the publication of his book, I Was Stalin's Agent, wrote about it in America in 1956. It was at first officially denied that there had been a spy named King. The Foreign Office statement admitting it only came when it was discovered that a member of the House of Commons had the information and was going to speak about in Parliament.

In 1956 King was traced by journalists to a London block of apartments where he was living in obscurity. After first attempting to deny his identity, he eventually admitted that he had done "stupid things, but I never gave any information to the Soviets." He then went on to argue that he found himself "up against the powers that be, the War Office and the Foreign Office. I never knew where the information against me came from. I never really understood the charges. But when you are up against the powers that be there is nothing you can do. Trial is a formality. I pleaded guilty and the trial took only a matter of minutes."

Primary Sources

(1) Gary Kern, A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror (2004)

From his list Bystrolyotov targeted cipher clerks working in Geneva with the British delegation to the League of Nations. He assigned two agents to cultivate them, but one, an uncouth sailor named Basov, gave himself away. The other, Han Pieck, an urbane and articulate artist with a wide circle of cultured friends, speaking English without an American accent, was much more successful. He befriended Raymond Oake, code-named SHELLEY, invited him to visit his home in The Hague and eventually recruited him in London. The motive, as in the case of Oldham, was money: Oake had served fourteen years in the Foreign Office and still was listed as temporary employment without a chance for a pension. During the cultivation phase, a time of engaging conversation and social drinking, Oake introduced Pieck to another encrypter in Geneva, also in the FO, who proved as hard up for money as himself.

Captain John Herbert King was another "temporary" clerk without a pension or decent prospects for the future. Over beer with Pieck, he expressed himself as a disgruntled Irishman, a victim of English discrimination, under appreciated and underpaid. He had a son who deserved the best things in life and an American mistress whose tastes were not inexpensive. Pieck sympathized. He and his wife took King and his mistress on a paid vacation to Spain and made King hunger for the pleasures of high society. Then, when he could not afford them, Pieck made his pitch back in London. It was March 1935....

In July 1937 Maly was recalled to Moscow and his agents were put on ice, as they were considered tainted by his supposed ideological impurity. Thus, King was cold and invisible to counterintelligence for a period of time. Krivitsky would have known about this, as he was still with the apparatus in Paris when Maly went back to Moscow; but he had little information thereafter. He received a letter from Maly in August 1937, defected in October, then heard from Bassoff in Times Square a year and a half later that Maly was still alive. It was a lie: Maly had been executed at the end of 1937. Consequently, Krivitsky did not know whether Maly or a replacement had come back to England and reactivated King. Nor does the literature reveal King's status at the time that Levine pronounced his name to Lord Lothian. At the very least, if not currently working for the Bolsheviks, the code clerk was a dangerous "sleeper" ready for reactivation. Receiving the ambassador's urgent telegram, MI5 located the one man named King in the Communications Department and, as he was reportedly exhausted from work, gave him a two-week leave so as to facilitate a full-scale investigation and surveillance.

(2) Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (2009)

The successes of Soviet agent penetration during the 1930s were made possible by Whitehall's still primitive grasp of protective security. Moscow had vastly more intelligence about British policy than the British intelligence community had about the Soviet Union's. Until the Second World War the Foreign Office had no security officer let alone a security department. Hence the relative ease with which the OGPU/NKVD recruited FO cipher clerks in the early 1930s. The Centre believed that the first of the cipher clerks to be recruited, Ernest Oldham, was discovered by MIS or the Foreign Office and assassinated in 1933. In reality, Oldham committed suicide and his treachery was not discovered until the Second World War. Captain John King, the most productive of the FO cipher-clerk recruits, also went undiscovered until the outbreak of war.

(3) John Costello and Oleg Tsarev, Deadly Illusions (1993)

One of the names passed to Moscow by Bystrolyotov was Captain John Herbert King, who was attached to the British League of Nations delegation in Geneva. Estranged from his wife and saddled with the burden of maintaining a free-spending American mistress, King was living way beyond his means. He became vulnerable to cultivation with Soviet money through expenses-paid Spanish holidays arranged by Henri Christian (Hans) Pieck, a Dutch artist, who was one of the NKVD's roster of agents in The Hague who were being run by Maly, the Centre's so-called "flying illegal". When King returned to London late in 1934, he began supplying Pieck with Foreign Office cables under the illusion that he was helping his friend's Dutch banker compile information on international trade relations. Assigned the code name MAG, King soon graduated to become a very valuable source for the Centre with his wholesale removal of copies of the Foreign Office cables he encoded, a role he continued to play until he was exposed by the Soviet defector Walter Krivitsky in the autumn of 1939. Information gleaned from Oldham and King enabled the Centre, with Maclean's help, to kick the door into the Foreign Office and its secrets wide open.'

The WAISE dossier reveals how, from the beginning of January 1936, when he handed his first bundle of Foreign Office papers to Deutsch, Maclean smuggled out an ever growing volume of documents. These were photographed overnight and handed back, to return the next morning. The volume soon became so great Deutsch instructed Maclean that, whenever possible, he should bring the documents out on a Friday night to give the overworked photographer of the "illegal" station two days to work before the papers were returned on Monday morning. The quantity and quality of the intelligence flowing from this source to Moscow picked up dramatically as Maclean gained both in expertise and confidence. No one in his office appeared to bother about the increasing amount of documentation he was ostensibly taking home to work on in his Chelsea bachelor flat in Oakley Street, a stone's throw from the Thames.

The reservoir of Foreign Office intelligence Maclean tapped opened up such a flood of documentation that Deutsch was soon overwhelmed. Following Orlov's departure, he had assumed the burden of heading the London "illegal" station and found it increasingly difficult to service Maclean in addition to taking care of the network, vetting new recruits and handling all the technical matters. Orlov's response to this overload on Deutsch was to send the INO Chief Slutsky a memorandum which concluded, "Taking into consideration the importance of the above-mentioned material and information that has fallen into our hands, in addition to the importance of other cultivations and recruitments that could benefit our field stations abroad, I consider the question of the Foreign Department's assigning an experienced and talented underground resident to head the field station in the British Isles to be extremely pressing.

Theodore Maly, one of the Centre's top agents, had by then been dispatched to England under the cryptonym MANN in January 1936 with sole responsibility for handling the material supplied by MAG, the code clerk King. The Chiefs did not immediately authorize him to give assistance to Deutsch's group. But, since Maly was a proficient and capable "illegal" who had experience in both counter-intelligence and agent operations, Orlov eventually prevailed on the Foreign Department. Maly was recalled to Moscow for briefing with Orlov and, by April 1936 had returned as the newly designated London resident with responsibility over Deutsch for the running and development of the Cambridge group.

(4) Theodore Maly, report to Moscow (24th May 1936)

Tonight WAISE (Donald Maclean) arrived with an enormous bundle of dispatches, of which MAG (King) had supplied only a few. Only part of them have been photographed, which we have marked with a W, because we have run out of film and today is Sunday - and night-time at that. We wanted him (Maclean) to take out a military intelligence bulletin, but he did not succeed in doing this. On Saturday he must stay on duty in London and we hope that he will be able to bring out more, including those which he has not managed to get out yet.

(5) Richard Deacon, A History of the Russian Secret Service (1972)

The case of Captain John Herbert King is a peculiar one. In June 1956 Isaac Levine, an anti-Communist writer, gave evidence to a United States Senate Investigation Committee that in 1939 the British executed a Soviet agent named King who was found working in the cipher room of the Imperial War Council. This was the same Isaac Levine who had written Krivitsky's memoirs and he revealed that it was Krivitsky's testimony about the presence of spies in the British Foreign Office when he defected to the West that enabled the Americans to tip off the British.

A day later the British Foreign Office revealed for the first time that on 18 October 1939 Captain John Herbert King, a retired Army officer, was sentenced to ten years' penal servitude for passing information to the Russian Government. King worked in the Communications Department of the Foreign Office (this was not the same as the archives section, though the Italian agent could have made a mistake), which handled messages in code and cipher. King was then fifty-five and the trial was held in secret under the Emergency Powers Regulations. The Foreign Office statement added that King was "believed still to be alive and in Britain. He had remission for good conduct and did not serve his full sentence."

The case of Captain King seems to have been curious in a number of ways. The trial was held in the No. 1 Court of the Old Bailey before Mr. Justice Hilbery in conditions of great secrecy. King was the first spy to be tried in Britain in World War II and the M.I.5 agents who trapped him went to the Old Bailey in a curtained car. All corridors were cleared. But though it is customary in wartime for such trials to be held in secret, normally the result and sentence are publicised. In the case of Captain King no details were published and everything was hushed up. Indeed, when Levine gave his evidence in the U.S.A. in 1956 it was at first officially denied that there had been a spy named King. The Foreign Office statement followed only when it was obvious that awkward questions were going to be asked by at least one Member of Parliament.

The question arises as to whether King was given preferential treatment despite the enormity of his offences. By mutual agreement the truth about them was kept a secret when he went to prison and other prisoners in Maidstone and Camp Hill jails, where he was sent, thought he had merely been convicted for a passport offence. Spies in British jails - at that time, if not today - were the most hated of prisoners except for those guilty of offences against children. King was popular with his fellow prisoners and he played the violin in the prison orchestra along with a professional violinist who had been jailed for distributing seditious literature.

It was also curious that he was frequently moved from prison to prison as though the authorities were afraid of other prisoners getting to know his secret if he remained anywhere too long.

Both the British and the Russian Secret Services suffered serious setbacks at this time, yet only the Russians seemed to learn any lessons from them. The latter were quickly made aware that their own traitor was General Walter Krivitsky, but the British not only failed to realise the fact that they had been infiltrated in their own Foreign Office, they took no steps to ascertain who the other traitors were. It was this failure on their part to act which raises the question of whether the Soviet had not infiltrated the Foreign Office, or the Secret Service at a much higher level. For the facts available at that time must have been suppressed by somebody high up in either the Foreign Office or the Secret Service.

There was a definite link between King and Sidney Reilly: the two men had known one another and had kept in touch in the early 'twenties when King was attached to the British Embassy in Paris. Even though Reilly had disappeared in Russia more than twelve years previously, his contacts in Britain were still being used.

But if this alone should have warned the British, Krivitsky's testimony should have alerted them to further dangers. The Americans had paid scant heed to Krivitsky's warnings about the extent to which the Russians had penetrated some Western Intelligence Services. They had passed on the information to the British Embassy in Washington, who in turn informed London. Krivitsky was sent secretly to Britain and it was his information that led to M.I.5 watching King and finally having him arrested by the Special Branch. But there were some in London who were suspicious of Krivitsky, while there were others, notably in the Secret Service, who felt that he had not told all he knew, that something was being held back for fear of the consequences. This was true. Krivitsky had a premonition that somebody in London had informed Moscow of his visit and that this had sealed his fate. He realised that if the N.K.V.D. knew what he had done, a Soviet assassination team would be given the task of locating and liquidating him.

"When Krivitsky got back to New York," van Narvig told me, "he was certain that he had made a great error in going to London. I asked him why and he replied, `One just cannot trust the British. The Soviet Union has spies there in very high places. One never knows who is a friend or an enemy.' I told him not to be foolish and he added, "You know the agent Reilly? It was his information which enabled the Russians to penetrate the British network. He thought that by telling us a little he could help Britain and save himself. In the end he did not help Britain and he did not save

himself."One of the items of information Krivitsky gave the British pointed clearly in the direction of Donald Maclean. He also stated that the Soviet had spent a sum of more than £70,000 trying to infiltrate key Government posts in London. Yet nothing was done to locate the "young Scotsman with bohemian tastes" in the British Foreign Office.

Van Narvig's comments on all this were equally shrewd. "There never was any chance that the Soviet Union would make any agreement with Britain when talks began in the early summer of 1939. They knew that in the British Foreign Office and the Secret Service were men of influence who were predominantly anti-Bolshevik and pro-German. They knew this because their own agents inside both the F.O. and the S.I.S. told them. They knew perfectly well that these forces would like nothing better than to see Germany and Russia engaged in war while Britain and France looked on from behind the Maginot Line."

It is true that this mentality existed in British governing circles at the time and in the Foreign Office itself, but a disservice was done both to Britain and Russia by those Soviet agents who had infiltrated Britain almost hysterically exaggerating the extent of this viewpoint in their reports. The ideological prejudices of an agent such as Maclean were enough to prevent him from being sufficiently objective. It was only after Churchill came to power in 1940 that the situation changed and by then Stalin was far too mistrustful to listen to the British Government's genuine warnings of a coming German invasion of Russia.