Liverpool and Manchester Railway

The Stockton & Darlington line opened in 1825 successfully reduced the cost of transporting coal from 18s. to 8s. 6d. a ton. It soon became clear that large profits could be made by building railways. A group of businessmen led by James Sandars recruited George Stephenson to build them a railway. The main objective was to reduce the costs of transporting raw materials and finished goods between Manchester, the centre of the textile industry and Liverpool, the most important port in the north of England.

The proposed Liverpool & Manchester Railway was a serious economic threat to the Bridgewater Canal. that was making a fortune by shipping goods between Liverpool and Manchester. In 1825 shares in the company, originally purchased at £70, were selling at £1,250 and paying an annual dividend of £35. The Marquis of Stafford, who became the principal owner of the canal after the death of the Duke of Bridgewater, was making an annual profit of £100,000 from the venture, and unstandably led the fight against the planned railway. Turnpike Trusts, coach companies and farmers also voiced their opposition.

After the House of Commons rejected Stephenson's proposed route, James Sandars recruited a company run by George Rennie to carry out a new survey and were invited by the company to build it. However, they refused to work with George Stephenson, who they did not consider was a real engineer, and they lost the contract.

After several years of debate, Parliament gave permission for the Manchester & Liverpool Railway to be built in 1826. George Stephenson was faced with a large number of serious engineering problems. This included crossing the unstable peat bog of Chat Moss, a nine-arched viaduct across the Sankey Valley and a two-mile long rock cutting at Olive Mount.

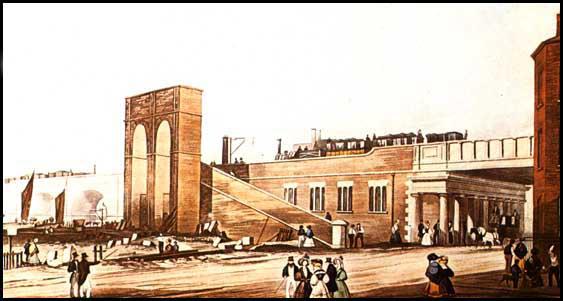

The Liverpool & Manchester railway was 31 miles long and consisted of a double line of rails of the fish-bellied type and laid on stone or timber sleepers. Passenger trains started at the Crown Street Station in Liverpool and after passing Moorish Arch at Edge Hill terminated at Water Street in Manchester.

The directors of the Liverpool & Manchester company were unsure whether to use locomotives or stationary engines on their line. To help them reach a decision, it was decided to hold a competition where the winning locomotive would be awarded £500. The idea being that if the locomotive was good enough, it would be the one used on the new railway.

The competition was held at Rainhill during October 1829. Each competing locomotive had to haul a load of three times its own weight at a speed of at least 10 mph. The locomotives had to run twenty times up and down the track at Rainhill which made the distance roughly equivalent to a return trip between Liverpool and Manchester. Afraid that heavy locomotives would break the rails, only machines that weighed less than six tons could compete in the competition. Ten locomotives were originally entered for the Rainhill Trials but only five turned up and two of these were withdrawn because of mechanical problems. Sans Pareil and Novelty did well but it was the Rocket, produced by George and his son, Robert Stephenson, that won the competition.

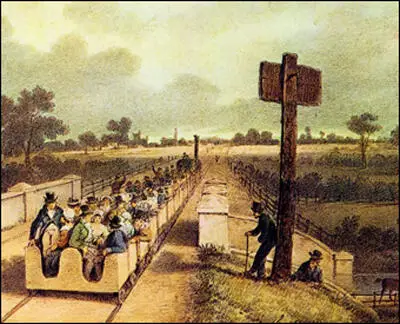

The Liverpool & Manchester railway was opened on 15th September, 1830. The prime minister, the Duke of Wellington, and a large number of important people attended the opening ceremony that included a procession of eight locomotives, including the Northumbrian, the Rocket, the North Star and the Phoenix.

After the group of special visitors were given a ride on the Northumbrian, William Huskisson, one of Liverpool's MPs crossed from his own carriage to speak to the Duke of Wellington. Warnings were shouted when people realised that the Rocket, driven by Joseph Locke, was about to pass the Northumbrian. Huskisson was unable to escape and was knocked down by the Rocket. The locomotive badly mangled one of his legs. A doctor attempted to stem the bleeding and George Stephenson used the Northumbrian to take him for further treatment. Despite these attempts to save him, Huskisson died later that day.

crossing the Bridgewater Canal by A. B. Clayton.

With large crowds assembled along the line between Liverpool and Manchester it was decided to continue with the procession. However, when the Northumbrian entered Manchester the passenger carriages were pelted with stones by weavers, who remembered the Duke of Wellington's involvement in the Peterloo Massacre and his strong opposition to the the proposed 1832 Reform Act.

The Liverpool & Manchester railway was a great success. In 1831 the company transported 445,047 passengers. Receipts were £155,702 with profits of £71,098. By 1844 receipts had reached £258,892 with profits of £136,688. During this period shareholders were regularly paid out an annual dividend of £10 for every £100 invested.

Primary Sources

(1) William James, letter to Joseph Sandars (September, 1822).

At Manchester the subject of the railway encourages all men's thoughts. The canal companies are alive to the danger. I am the object of their persecution and hate; they would immolate me if they could.

(2) Liverpool and Manchester Railroad Company Prospectus (1824)

The Committee of the Liverpool and Manchester Railroad Company think it right to state, concisely, the grounds upon which they rest their claims to public encouragement and support.

The importance, to a commercial state, of a safe and cheap mode of transit for merchandise, from one part of the country to another, will be readily acknowledged. This was the plea, upon the first introduction of canals: it was for the public advantage; and although the new mode of conveyance interfered with existing and inferior modes, and was opposed to the feelings and prejudices of landholders, the great principle of the public good prevailed, and experience has justified the decision.

It is upon the same principle that railroads are now proposed to be established; as a means of conveyance manifestly superior to existing modes: possessing, moreover, this recommendation, in addition to what could have been claimed in favour of canals, namely, that the railroad scheme holds out to the public not only a cheaper, but far more expeditious conveyance than any yet established....

In deciding upon the proposed route, the committee have been anxious, at considerable inconvenience and expense, to select a line which may not only be eligible.... but may be as little objectionable as possible, with reference to individual and local interest.

The ground has been surveyed by eminent engineers, and the estimated expense of a railroad, upon the most improved construction, including the charge for locomotive engines to be employed on the line, and other contingencies, is £400,000 - which sum it is proposed to raise in 4,000 shares of £100 each.

The total quantity of merchandise passing between Liverpool and Manchester is estimated, by the lowest computation, at 1,000 tons per day. The bulk of this merchandise is transported either by the Duke of Bridgewater's Canal, or the Mersey and Irwell Navigation. By both of these conveyances goods must pass up the river Mersey, a distance of 16 or 18 miles, subject to serious delays from contrary winds, and not unfrequently, to actual loss or damage from tempestuous weather. The average length of passage, by these conveyances, including the customary detention on the wharfs, may be taken at 36 hours.... The average charge upon merchandise for the last 14 years has been about 15s. per ton.

By the projected railroad, the transit of merchandise between Liverpool and Manchester will be effected in four or five hours, and the charge to the merchant will be reduced at least one-third. Here, then, will be accomplished an immense pecuniary saving to the public, over and above what is perhaps still more important, the economyy of time.... It will afford a stimulus to the productive industry of the country; it will give a new impulse to the powers of accumulation, the value and importance of which can be fully understood only by those who are aware how seriously commerce may be impeded by petty restrictions, and how commercial enterprise is encouraged and promoted by an adherence to the principles of fair competition and free trade.

The committee are aware that it will not immediately be understood by the public how the proprietors of a railroad, requiring an invested capital of £400,000 can afford to carry goods at so great a reduction upon the charge of the present water companies.... It is not that the water companies have not been able to carry goods on more reasonable terms, but that, strong in the enjoyment of their monopoly, they have not thought proper to do so.... IT IS COMPETITION THAT IS WANTED....

But it is not altogether on account of the exorbitant charges of the water-carriers that a railroad is desirable. The present canal establishments are inadequate to ... the regular and punctual conveyance of goods at all periods and seasons. In summer time there is frequently a deficiency of water, obliging boats to go only half-loaded... while, in winter, they are sometimes locked up with frosts, for weeks together.... There is still another ground of objection to the present system of carriage by canals, namely, the pilferage, an evil for which there is seldom adequate redress ... whereas, a conveyance by railway, effected in a few hours, and where every delay must be accounted for, may be expected to possess much of the publicity and consequent safety of the king's highways.

In addition to the transport of goods between Liverpool and Manchester, an important branch of revenue may be expected to result to the proprietors of the projected road, from the conveyance of coals from the rich mines in the vicinity of St. Helens.... These coals at present pass along the Sankey Canal, and down the Mersey to Liverpool, a distance of about 30 miles. By the railway the distance will be shortened one-half, and the charge for transit very materially reduced.

Amongst the widely-diffused benefits to be expected from the proposed railroad, must especially be enumerated, no inconsiderable advancement in the commercial prosperity of Ireland. The latent energies of that country, her capabilities as a manufacturing power, will be developed by being brought into easy contact and communication with the manufacturing districts of this kingdom; while every article of her agricultural industry will experience an increased demand, from the cheapness and facility with which it will be introduced into the populous counties of Lancaster and York....

In the present state of trade and of commercial enterprise, dispatch is no less essential than economy. Merchandise is frequently brought across the Atlantic from New York to Liverpool in 21 days; while, owing to the various causes of delay above enumerated, goods have in some instances been longer on their passage from Liverpool to Manchester....

The immediate and prominent advantages to be anticipated from the proposed railroad are, increased facilities to the general operations of commerce, arising out of that punctuality and dispatch which will attend the transit of merchandise between Liverpool and Manchester, as well as a pecuniary saving to the trading community. But the inhabitants at large of these populous towns will reap their full share of direct and immediate benefit. Coals will be brought to market in greater plenty, and at a reduced price; and farming produce, of various kinds, will find its way from greater distances, and at more reasonable rates. To the landlords, also, in the vicinity of the line, the railroad offers important advantages in extensive markets for their mineral and agricultural produce, as well as in a facility of obtaining lime and manure at a cheap rate in return. Moreover, as a cheap and expeditious means of conveyance for travellers, the railway holds out the fair prospect of a public accomodation, the magnitude and importance of which cannot be immediately determined.

The committee do not think it necessary to dwell upon probable and contingent sources of revenue to the proprietors, and of benefit to the community; but it is impossible entirely to overlook the tendency of increased economy and dispatch to extend the commercial intercourse, not only upon the immediate line of road, but diverging in ramifications to the north and south, and especially towards the rich and populous town of Bolton; a short branch line being sufficient to bring that extensive manufacturing district into rapid and direct communication with this port ….

(3) On 25th April, 1825, George Stephenson gave evidence to the House of Commons committee looking into the proposed Liverpool & Manchester Railway. Edward Alderson, the counsel employed by those opposing the railway, severely criticised the evidence given by Stephenson.

This railway is the most absurd scheme that ever entered into the head of a man to conceive. Mr. Stephenson never had a plan - I do not believe he is capable of making one. He is either ignorant or something else which I will not mention. His is a mind perpetually fluctuating between opposite difficulties; he neither knows whether he is to make bridges over roads or rivers, or of one size or another; or to make embankments, or cuttings, or inclined planes, or in what way the thing is to be carried into effect. When you put a question to him upon a difficult point, he resorts to two or three hypothesis, and never comes to a decided conclusion. Is Mr. Stephenson to be the person upon whose faith this Committee is to pass this Bill involving property to the extent of £400,000/£500,000 when he is so ignorant of his profession as to propose to build a bridge not sufficient to carry off the flood water of the river or to permit any of the vessels to pass which of necessity must pass under it.

(4) George Stephenson wrote to Michael Longridge about how the canal companies were trying to stop the building of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway.

Lord Derby, Lord Sefton and Bradshaw the great Canal Proprietor, whose grounds we go through with the projected railway, have been trying to stop us. The ground is lockaded on every side to prevent us getting on with the survey. Bradshaw fires guns to prevent the surveyors coming in the dark. Lord Sefton says he will have a hundred men against us. The company thinks these great men have no right to stop a survey.

(5) The Quarterly Review supported the building of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway but warned against the dangers of allowing locomotives to travel too fast (March, 1825)

What can be more palpably absurd than the prospect held out of locomotives travelling twice as fast as stagecoaches! We trust that Parliament will, in all railways it may sanction, limit the speed to eight or nine miles an hour.

(6) In 1824 the Liverpool & Manchester Railroad Company published a prospectus that invited people to invest in the company.

The total quantity of goods passing between Liverpool and Manchester is estimated to be 1,000 tons per day. The average length of time taken by canal is 36 hours. The average charge has been 15s a ton. By the projected railroad, the transit of goods between Liverpool and Manchester will be four of five hours, and the charge to the merchant reduced by at least one-third.

(7) Henry Booth, Account of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (1830).

Perhaps the most striking result produced by the completion of this railway, is the sudden change which has been effected in our ideas of time and space. What was quick is now slow; what was distant is now near.

(8) Fanny Kemble, a leading actress, was invited to attend the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.

The most intense curiosity and excitement prevailed, and though the weather was uncertain, enormous masses of densely packed people lined the road, shouting and waving hats and handkerchiefs as we flew by them. We travelled at 35 miles an hour (swifter than a bird flies). When I closed my eyes this sensation of flying was quite delightful.

I had been unluckily separated from my mother in the first distribution of places, but by an exchange of seats which she was enabled to make she rejoined me when I was at the height of my ecstasy, which was considerably damped by finding that she was frightened to death, and intent upon nothing but devising means of escaping from a situation which appeared to her to threaten with instant annihilation herself and all her travelling companions.

When we neared Manchester the sky grew cloudy and dark, and it began to rain. The vast concourse of people who had assembled to witness the triumphant arrival of the successful travellers was of the lowest orders of mechanics and artisans, among whom great distress and a dangerous spirit of discontent with the government at that time prevailed. Groans and hisses greeted the carriage, full of influential personages, in which the Duke of Wellington sat.

High above the grim and grimy crowd of scowling faces a loom had been erected, at which sat a tattered, starved-looking weaver, evidently set there as a representative man, to protest against the triumph of machinery and the gain and glory which the wealthy Liverpool and Manchester men were likely to derive from it.

(9) Lady Wilton was in the Duke of Wellington's carriage when William Huskisson had his accident. She later told Fanny Kemble what happened.

The engine had stopped to take a supply of water, and several of the gentlemen in the directors' carriage had jumped out to look about them. Lord Wilton, Count Batthyany, Count Matuscenitz and Mr. Huskisson among the rest were standing talking in the middle of the road, when and engine on the other line, which was parading up and down merely to show its speed, was seen coming down upon them like lightening. The most active of those in peril sprang back into their seats; Lord Wilton saved his life only by rushing behind the Duke's carriage, and Count Matuscenitz had but just leaped into it, with the engine all but touching his heels as he did so; while poor Mr. Huskisson, less active from the effects of age and ill-health, bewildered, too, by the frantic cries of "Stop the engine! Clear the track!" that resounded on all sides, completely lost his head, looked helplessly to the right and left, and was instantaneously prostrated by the fatal machine, which dashed down like a thunderbolt upon him, and passed over his leg, smashing and mangling it in the most horrible way.

(10) The Sunday Observer (19th September 1830)

The great national work was opened to the public on Wednesday last, with all the ceremonies befitting such an important occasion. The Duke of Wellington, Mr. Huskisson, Sir R. Peel, Prince Esterhazy, and Mr. Holmes were guests of the Committee, together with almost every person of consideration in the neighbouring counties. The project of establishing a correspondence by railway between two of the most populous and important towns in the kingdom, was not started till 1824, when a Mr. James proposed it. The rate of travelling is spoken of as being likely to average about sixteen or eighteen miles an hour.

Several of the passengers of the Northumbrian got out to walk on the railway, and among them was Mr. Huskisson. He was discoursing with Mr. J. Sanders, one of the principal originators and promoters of the railroad, when the Rocket engine came slowly up, and as the engineer had been for some time checking its velocity, so silently that it was almost upon the group before they observed it. In the hurry of the moment all attempted to get out of the way. Mr Huskisson hesitated, staggered a little, as if not knowing what to do, then attempted again to get into the carriage. As he took hold of the door to do this, but the motion threw him off balance, and before he could recover he was thrown down directly in the path of the Rocket. Mrs. Huskisson, who, along with several other ladies, witnessed the accident, uttered a shriek of agony, which none who heard will ever forget.