1832 Reform Act

Between 1770 and 1830, the Tories were the dominant force in the House of Commons. The Tories were strongly opposed to increasing the number of people who could vote. However, in November, 1830, Earl Grey, a Whig, became Prime Minister. Grey explained to William IV that he wanted to introduce proposals that would get rid of some of the rotten boroughs. Grey also planned to give Britain's fast growing industrial towns such as Manchester, Birmingham, Bradford and Leeds, representation in Parliament. (1)

In March 1831 Grey introduced his reform bill. Princess Dorothea Lieven, the wife of the Russian ambassador, commented: "I was absolutely stupefied when I learnt the extent of the Reform Bill. The most absolutely secrecy has been maintained on the subject until the last moment. It is said that the House of Commons was quite taken by surprise; the Whigs are astonished, the Radicals delighted, the Tories indignant. This was the first impression of Lord John Russell's speech, who was entrusted with explaining the Government Bill. I have had neither the time nor the courage to read it. Its leading features have scared me completely: 168 members are unseated, sixty boroughs disfranchised, eight more members allotted to London and proportionately to the large towns and counties, the total number of members reduced by sixty or more." (2)

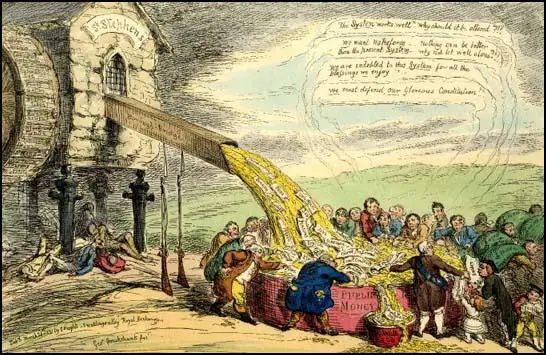

The House of Commons is shown as a water mill. The water wheel bear the names of rotten

boroughs. Underneath lies the corpses of the poor, and from the mill pours a stream of benefits

of being MPs, which they stuff in their pockets, while praising the system and opposing reform.

The 1831 Reform Bill was passed by the House of Commons. According to Thomas Macaulay: "Such a scene as the division of last Tuesday I never saw, and never expect to see again. If I should live fifty years the impression of it will be as fresh and sharp in my mind as if it had just taken place. It was like seeing Caesar stabbed in the Senate House, or seeing Oliver taking the mace from the table, a sight to be seen only once and never to be forgotten. The crowd overflowed the House in every part. When the doors were locked we had six hundred and eight members present, more than fifty five than were ever in a division before". (3)

House of Lords and Parliamentary Reform

The following month the Tories blocked the measure in the House of Lords. Grey asked William IV to dissolve Parliament so that the Whigs could show that they had support for their reforms in the country. Grey explained this would help his government to carry their proposals for parliamentary reform. William agreed to Grey's request and after making his speech in the House of Lords, walked back through cheering crowds to Buckingham Palace. (4)

Polling was held from 28th April to 1st June 1831. In Birmingham and London it was estimated that over 100,000 people attended demonstrations in favour of parliamentary reform. William Lovett, the head of the National Union of the Working Classes, gave his support to the reformers standing in the election. The Whigs won a landslide victory obtaining a majority of 136 over the Tories. After Lord Grey's election victory, he tried again to introduce parliamentary reform. Enormous demonstrations took place all over England and in Birmingham and London it was estimated that over 100,000 people attended these assemblies. They were overwhelmingly composed of artisans and working men. (5)

On 22nd September 1831, the House of Commons passed the Reform Bill. However, the Tories still dominated the House of Lords, and after a long debate the bill was defeated on 8th October by forty-one votes. When people heard the news, Reform Riots took place in several British towns; the most serious of these being in Bristol in October 1831, when all four of the city's prisons were burned to the ground. In London, the houses owned by the Duke of Wellington and bishops who had voted against the bill in the Lords were attacked. On 5th November, Guy Fawkes was replaced on the bonfires by effigies of Wellington. (6)

Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, complained: "This detestable Reform Bill has raised the hopes of the utmost. At Plymouth and the neighbouring towns, the spirit is tremendously bad. The shopkeepers are almost all Dissenters, and such is the rage on the question of Reform at Plymouth, that I have received from several quarters the most earnest requests that I will not come to concentrate a church, as I had engaged to do. They assure me that my own person, and the security of the public peace, would be in the greatest danger." (7)

Reform Riots

Lord Grey argued in the House of Commons that without reform he feared a violent revolution would take place: "There is no one more decided against annual parliaments, universal suffrage, and the ballot, than I am. My object is not to favour but to put an end to such hopes and projects." (8) The Poor Man's Guardian agreed and it commented that the ruling class felt that "a violent revolution is their greatest dread". (9)

Grey attempted negotiation with a group of moderate Tory peers, known as "the waverers", but failed to win them over. On 7th May a wrecking amendment was carried by thirty-five votes, and on the following day the cabinet resolved to resign unless the king would agree to the creation of peers. On 7th May 1832, Grey and Henry Brougham met the king and asked him to create a large number of Whig peers in order to get the Reform Bill passed in the House of Lords. William was now having doubts about the wisdom of parliamentary reform and refused. (10)

Lord Grey's government resigned and William IV now asked the leader of the Tories, the Duke of Wellington, to form a new government. Wellington tried to do this but some Tories, including Sir Robert Peel, were unwilling to join a cabinet that was in opposition to the views of the vast majority of the people in Britain. Peel argued that if the king and Wellington went ahead with their plan there was a strong danger of a civil war in Britain. He argued that Tory ministers "have sent through the land the firebrand of agitation and no one can now recall it." (11)

1832 Reform Act

When the Duke of Wellington failed to recruit other significant figures into his cabinet, William was forced to ask Grey to return to office. In his attempts to frustrate the will of the electorate, William IV lost the popularity he had enjoyed during the first part of his reign. Once again Lord Grey asked the king to create a large number of new Whig peers. William agreed that he would do this and when the Lords heard the news, they agreed to pass the Reform Act. According to the Whig MP, Thomas Creevey, by taking this action, Grey "has saved the country from confusion, and perhaps the monarch and monarchy from destruction". (12)

Creevey went on to state that it was a great victory against the Tories: "Thank God! I was in at the death of this Conservative plot, and the triumph of the Bill! This is the third great event of my life at which I have been present, and in each of which I have been to a certain extent mixed up - the battle of Waterloo, the battle of Queen Caroline, and the battle of Earl Grey and the English nation for the Reform Bill." (13)

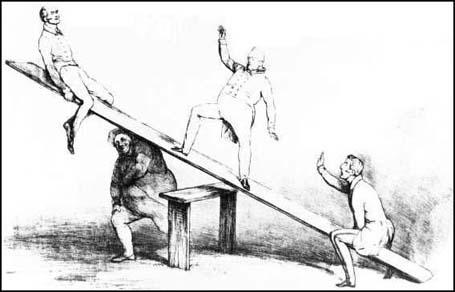

Earl Grey , the British population, William IV and Duke of Wellington (May, 1832)

A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) has argued that the most import change was that it placed "political power in the hands of the industrial capitalists and their middle class followers." (14) Most people were disappointed with the 1832 Reform Act. Voting in the boroughs was restricted to men who occupied homes with an annual value of £10. There were also property qualifications for people living in rural areas. As a result, only one in seven adult males had the vote. Nor were the constituencies of equal size. Whereas 35 constituencies had less than 300 electors, Liverpool had a constituency of over 11,000. "The overall effect of the Reform Act was to increase the number of voters by about 50 per cent as it added some 217,000 to an electorate of 435,000 in England and Wales. But 650,000 electors in a population of 14 million were a small minority." (15)

Primary Sources

(1) Princess Dorothea Lieven, letter to her brother Alexander von Benckendorff (November, 1830)

Just now there is a belief in universal suffrage... It is quite certain that the wrongs of the lower classes need a remedy. The aristocracy rolls in wealth and luxury while... the highways of the country, swarm with miserable creatures covered with rags, barefooted, having neither food nor shelter. The sight of this contrast is revolting, and in all likelihood were I one of these poor wretches I should be a democrat.

(2) Harriet Arbuthnot, diary entry (4th November, 1830)

Parliament was opened by the King on the 2nd. He was very well received by the people who, however, were very disorderly, hooted and hissed the Duke wherever they could see him. People complain that the Duke did harm by declaring publicly he would not lend himself to any reform and that he thought, in its results, no form of representation could be better than ours. I don't believe there will be any disturbance. The wretched state to which Belgium is reduced by their desire for reform is a pretty good lesson for sober and reflecting people such as we are.

(3) John Cab Hobhouse, diary entry (4th November, 1830)

The Duke of Wellington made a speech in the Lords, and declared against Reform. I hear he was hissed, and hurt by a stone. I heard this evening that a very unpleasant feeling was rising among the working classes, and that the shopkeepers in the Metropolis were so much alarmed that they talked of arming themselves.

(4) Harriet Arbuthnot, diary entry (7th November, 1830)

We hear the radicals are determined to make a riot. The King gets quantities of letters every day telling him he will be murdered. The King is very much frightened and the Queen cries half the day with fright.

The Duke is greatly affected by all this state of affairs. He feels that beginning reform is beginning revolution, and therefore he must endeavour to stem the tide as long as possible, and that all he has to do is to see when and how it will be best for the country that he should resign. He thinks he cannot till he is beat in the House of Commons. He talked about this with me yesterday.

(5) Princess Dorothea Lieven, letter to her brother Alexander von Benckendorff (2nd March, 1831)

I was absolutely stupefied when I learnt the extent of the Reform Bill. The most absolutely secrecy has been maintained on the subject until the last moment. It is said that the House of Commons was quite taken by surprise; the Whigs are astonished, the Radicals delighted, the Tories indignant. This was the first impression of Lord John Russell's speech, who was entrusted with explaining the Government Bill.

I have had neither the time nor the courage to read it. Its leading features have scared me completely: 168 members are unseated, sixty boroughs disfranchised, eight more members allotted to London and proportionately to the large towns and counties, the total number of members reduced by sixty or more.

(6) Thomas Macaulay, letter to Thomas Flower Ellis on the vote in the House of Commons on the Reform Act (30th March, 1831)

Such a scene as the division of last Tuesday I never saw, and never expect to see again. If I should live fifty years the impression of it will be as fresh and sharp in my mind as if it had just taken place. It was like seeing Caesar stabbed in the Senate House, or seeing Oliver taking the mace from the table, a sight to be seen only once and never to be forgotten. The crowd overflowed the House in every part. When the doors were locked we had six hundred and eight members present, more than fifty five than were ever in a division before.

When Charles Wood who stood near the door jumped up on a bench and cried out. "They are only three hundred and one." We set up a shout that you might have heard to Charing Cross - waving our hats - stamping against the floor and clapping our hands. The tellers scarcely got through the crowd. But you might have heard a pin drop as Duncannon read the numbers. Then again the shouts broke out - and many of us shed tears - I could scarcely refrain. And the jaw of Peel fell; and the face of Twiss was as the face of a damned soul. We shook hands and clapped each other on the back, and went out laughing, crying, and huzzaing into the lobby.

(7) Duke of Wellington, letter to Mr. Gleig (11th April, 1831)

The conduct of government would be impossible, if the House of Commons should be brought to a greater degree under popular influence. That is the ground on which I stand in respect to the question in general of Reform in Parliament.

(8) Duke of Wellington, letter to Harriet Arbuthnot (29th April, 1831)

I learn from my servant John that the mob attacked my House and broke about thirty windows. He fired two blunderbusses in the air from the top of the house, and they went off.

I think that John saved my house, or the lives of many of the mob - possibly both - by firing as he did. They certainly intended to destroy the house, and did not care one pin for the poor Duchess being dead in the house.

(9) Duke of Wellington, letter to Harriet Arbuthnot (1st May, 1831)

Matters appear to be going as badly as possible. It may be relied upon that we shall have a revolution. I have never doubted the inclination and disposition of the lower orders of the people. I told you years ago that they are rotten to the core. They are not bloodthirsty, but they are desirous of plunder. They will plunder, annihilate all property in the country. The majority of them will starve; and we shall witness scenes such as have never yet occurred in any part of the world.

(10) John Cam Hobhouse, Recollections of a Long Life (1910)

Lord John Russell began his speech at six o'clock. Never shall I forget the astonishment of my neighbours as he developed his plan. Indeed, all the House of Commons seemed perfectly astounded; and when he read the long list of the boroughs to be either wholly or partially disfranchised there was a sort of wild ironical laughter. Baring Wall, turning to me, said, "They are mad! They are mad!" and others made use of similar exclamations - all but Sir Robert Peel; he looked serious and angry, as if he had discovered that the Ministers, by the boldness of their measure, had secured the support of the country. Burdett and I agreed there was very chance of the measure being carried, and that a revolution would be the consequence. We thought our Westminster friends would oppose the £10 qualification clause; but we were wrong, for we found all our supporters delighted with the Bill.

(11) Charles Greville, journal (10th October, 1831)

Yesterday morning the newspapers (all in black) announced the defeat of the Reform Bill by a majority of forty-one, at seven o'clock on Saturday morning, after five nights' debating. By all accounts the debate was a magnificent display, and incomparably superior to that in the House of Commons, but the reports convey no idea of it.

The Duke of Wellington's speech was exceedingly bad; he is in fact, and has proved it in repeated instances, unequal to argue a great constitutional question. He has neither the command of language, the power of reasoning, nor the knowledge requisite for such an effort.

(12) Earl Grey, speech in the House of Commons (31st November, 1831)

There is no one more against annual parliaments, universal suffrage, and the secret ballot, than I am. My object is not to favour but to put an end to such hopes.

(13) Thomas Macaulay, speech in the House of Commons (31st November, 1831)

It is not by mere numbers, but by intelligence, that the nation ought to be governed... I support (the Reform Bill) because I am sure that it is our best security against a revolution.

(14) John Cob Hobhouse, Recollections of a Long Life (1910)

In Bond Street I saw a large placard with this inscription: "199 versus 22,000,000!" and I went into the house to persuade the shopman to take it down. He was a shoemaker, and, though very civil, was very firm, and refused to remove the placard, saying he had only done as others had done. When I told him who I was, he said, "Oh, I know you very well", but he still declined to follow my advice.

(15) The Observer (13th May, 1832)

At a quarter past twelve o'clock, the Royal carriage in which their Majesties were seated, without attendants, reached the village of Hounslow. The postillions passed on at a rapid rate till they entered the town of Brentford; where the people, who had assembled in great numbers, expressed by groans, hisses, and exclamations, their disapprobation of his Majesty's conduct with respect to the Administration. The Duke of Wellington had entered the Palace in full uniform about a quarter of an hour before the Majesties, and had been assailed by the people with groans and hisses. The Duke of Wellington, after remaining more than three hours with his Majesty, left about a quarter-past four, amidst groans and hisses even more vehement than when he arrived. Lord Frederick Fitzclarence was received with the same disapprobation, and loud cries of "Reform".

(16) Thomas Creevey, letter to Miss Ord about the Duke of Wellington and the passing of the Reform Act (26th May, 1832)

One more day will finish the concern in the Lords, and that this should have been accomplished as it has against a great majority of peers, and without making a single new one, must always remain one of the greatest miracles in English history. He (the Duke of Wellington) has destroyed himself and his Tory high-flying association for ever. This (the Reform Act) has saved the country from confusion, and perhaps the monarch and monarchy from destruction.

(17) Thomas Creevey, letter to Miss Ord on Earl Grey and the passing of the Reform Act (2nd June, 1832)

In the House of Lords yesterday Grey, according to his custom, came, and talked with me. It is really too much to see his happiness at its being all over. He dwells upon the marvellous luck of Wellington's false move.

(18) Thomas Creevey, letter to Miss Old on the passing of the Reform Act (5th June, 1832)

Thank God! I was in at the death of this Conservative plot, and the triumph of the Bill! This is the third great event of my life at which I have been present, and in each of which I have been to a certain extent mixed up - the battle of Waterloo, the battle of Queen Caroline, and the battle of Earl Grey and the English nation for the Reform Bill.

(19) Sir Denis Le Marchant, journal (5th June, 1832)

There were very few peers in the House during the ceremony of the Commission of assent. Ministers had been very anxious to avoid the appearance of triumph, so the time had been kept secret. The Duke of Sussex did not enter the body of the House but remained behind the curtain. When the assent was given, he said, loud enough to be heard at some distance, 'Thank God the deed is done at last. I care for nothing now - this is the happiest day of my life.' An old Tory standing behind him, lifted up his hands in horror, and fervently ejaculated, 'O Christ!'

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)