George Cruikshank

George Cruikshank was born in London on 27th September, 1792. His father, Isaac Cruikshank, was a successful caricaturist. After a brief education at an elementary school in Edgeware, Cruikshank worked with his father in his studio.

Richard A. Vogler, the author of The Graphic Works of George Cruikshank (1979) has pointed out that his artistic career began early: "His father earned a living doing drawings from song sheets and caricatures as well as etching plates after his own and other people's designs... As a child he produced some children's lottery prints and illustrations for chapbooks, a kind of commercial work he continued for several years."

Cruikshank wanted to study at the Royal Academy, but his father insisted that he needed his help in the studio. He taught him the rudiments of etching into copperplates; at the age of thirteen he was executing the titles of his father's caricatures, and also putting in backgrounds, furnishings, and dialogue.

Cruikshank's biographer, Robert L. Patten, has argued: "When, on 1st February 1803, Napoleon declared war on Britain... their father, Isaac, joined a Bloomsbury volunteer troupe while Robert and George drilled alongside with blackened mop handles and toy drums. Shortly thereafter Robert went to sea as a midshipman in the East India service; marooned on St Helena, he was given up for dead by his family until he returned, alive, in January 1806, having heard the fateful news of Trafalgar while on his way home. During Robert's absence, George aspired to replace him as a seaman. But Isaac's health was deteriorating, and he needed his son's assistance. Reluctantly, George agreed to remain in the studio, even hiding out on occasion from press-gangs."

By 1808 Cruikshank had developed his own style and was signing his prints with his full patronym: "G. Cruikshank". He produced hundreds of designs for advertisements and songheads. Principal patrons were Robert Laurie, Jemmy Whittle and Johnny Fairburn, one of the main printsellers in London. Inspired by the work of William Hogarth, Thomas Rowlandson and James Gillray, Cruikshank developed a reputation for his anti-establishment caricatures.

In early April 1811 Isaac Cruikshank, who was an alcoholic, won a drinking match and afterwards collapsed from acute alcoholic poisoning. He died a few days later. George was now the principal breadwinner and looked after his sister and mother until their deaths.

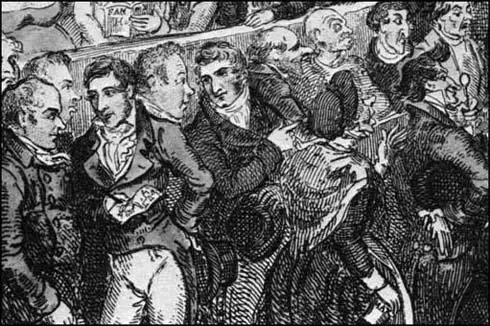

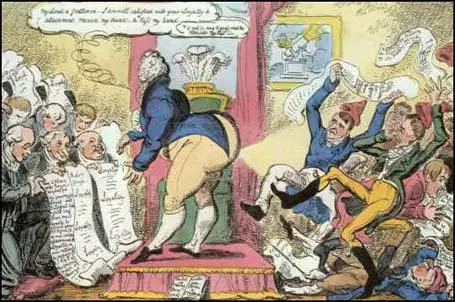

from left to right are William Jones, the publisher of The Scourge, George

Cruikshank, William Hone and George Cruikshank's brother, Robert..

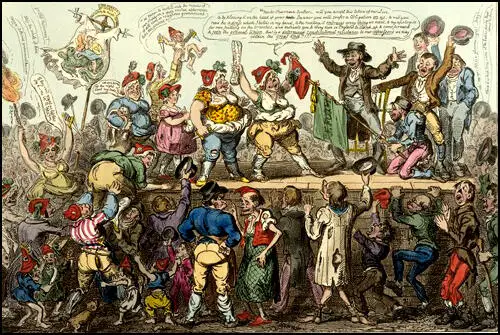

Cruikshank was now selling his drawings to over twenty different printsellers. This included a large caricature that appeared in each issue of William Jones's satirical magazine, The Scourge. (1811-1816). These early drawings included attacks on George III and the royal family and leading politicians such as Lord Castlereagh and Lord Sidmouth. The French poet, Charles Baudelaire, remarked, "The special merit of George Cruikshank is his inexhaustible abundance of grotesque.. The grotesque flows inevitably and incessantly from Cruikshank's etching needle, like pluperfect rhymes from the pen of a natural poet".

In 1818 George Cruikshank joined forces with Radical publisher and bookseller, William Hone, who was playing a leading role in the campaign against the Gagging Acts. In their struggle for press freedom, the two men produced The Political House that Jack Built. Hone later recalled he got the idea while reading the House That Jack Built to his four-year-old daughter. The 24 page pamphlet contained political nursery rhymes written by Hone and twelve illustrations by Cruikshank. The Political House That Jack Built was an immediate success selling over 100,000 copies in a few months.

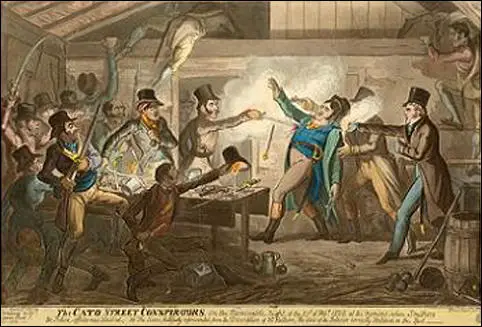

George Cruikshank, like many people, was deeply shocked by the Peterloo Massacre on 16th August, 1819. Cruikshank responded to this event by produced one of his most powerful drawings, Massacre at St. Peter's . The two men followed this success with a series of political pamphlets including The Queen's Matrimonial Ladder (1819) and The Man in the Moon (1820). In August 1821 the two men produced a mock newspaper, A Slap at Slop . Slop was Hone's name for John Stoddart, a former radical who had become the conservative editor of The Times.

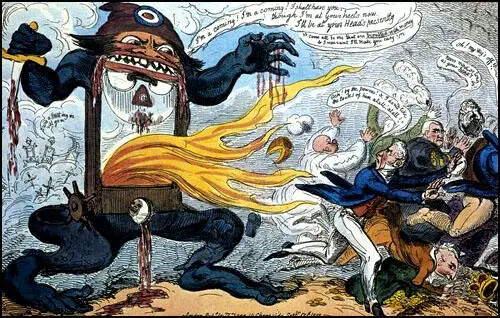

Cruikshank did not hold strong political beliefs and was willing to produce anti-radical prints for Tory booksellers like George Humphrey. This included Death and Liberty, a warning of the dangers that Radicals posed to the British Constitution and The Female Reformers of Blackburn , an attack on women becoming involved in politics. In September 1819 Cruikshank produced a Radical Reformer, a print that illustrated the threat of a French style revolution.

In September 1819 Thomas Tegg published Cruikshank's cartoon entitled A Radical Reformer, A Neck or Nothing Man! Dedicated to the Heads of the Nation. It showed a flame-belching, guillotine monster wearing the cap associated with French revolutionaries, which is terrorising Britain's leaders. "I'm a coming! I'm a coming! he says, I shall have you - though I'm at your heels now, I'll be at your Heads presently. Come all to me that are troubled with money & I warrant I'll make you easy!!" On the right the Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, falls over a bag of money. In front of him, Lord Castlereagh exclaims, "Och! by the powers! I don't like the looks of him at all, at all!" Upon hearing the Prince Regent (the future George IV) complain that he has lost his wig, Lord Eldon, the Lord Chancellor replies, "Never mind, so long as your head's on!".

Cruikshank did not hold strong political beliefs and was willing to produce anti-radical prints for Tory booksellers like George Humphrey. This included Death and Liberty, a warning of the dangers that Radicals posed to the British Constitution and The Female Reformers of Blackburn, an attack on women becoming involved in politics.

After the death of George III he targeted his son, George IV. The long-estranged princess of Wales came back to England to claim her status as queen, William Hone and Cruikshank took up Caroline's cause. These illustrated pamphlets sold as many as 100,000 copies in a few days. To spare himself from such devastating caricatures, in June 1820 the king directed that Cruikshank be paid £100 "not to caricature His Majesty in any immoral situation".

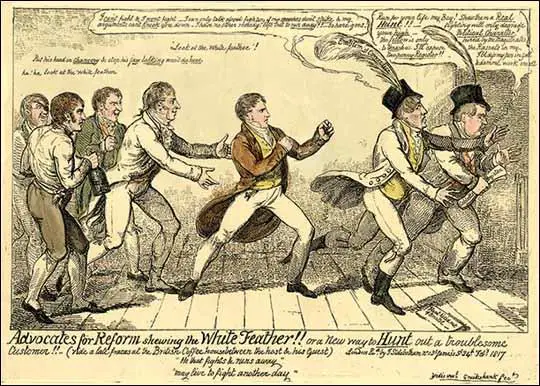

In the weeks following the Peterloo Massacre, George Prince of Wales received

petitions from Tory loyalists and Radicals demanding parliamentary reform.

Cruikshank now decided to concentrate on the less controversial work of book illustrations. With his brother he joined forces with Pierce Egan, to produce Life in London (1821). Egan's biographer, Dennis Brailsford, has pointed out: "Its popularity was instant and unprecedented, and the demand for copies increased with every month. Its attractions lay in both content and style, for its contrasting characters and scenes, setting the misery of low life against the prodigal waste and folly of high society, were all presented with vivacious dialogue and lively description and accompanied by the excellent illustrations of the brothers George and Robert Cruikshank."

Cruikshank then worked on a two volumes translation of the brothers Grimm's fairy tales into English. German Popular Stories was published 1823. Robert L. Patten has pointed out that "these delicate copperplate vignettes, so different from the coarser political satires of the preceding decade". John Ruskin later described the etchings "the finest things, next to Rembrandt's, that, as far as I know, have been done since etching was invented."

Like many artists, Cruikshank was unhappy about the changes that had resulted from the Industrial Revolution. In one print, London Going Out of Town - On the March of Bricks & Mortar (1829), Cruikshank attacked the building of houses on the green fields of Islington. In another print, The Horses 'Going to the Dogs (1829) he showed his dislike of the steam carriage that had been invented by Goldsworthy Gurney.

In 1835 Cruikshank was considered to be the most important graphic artist working in England. He decided to take advantage of this fame to start his own own publication, Cruikshank's Comic Almanack . William Makepeace Thackeray was one of the writers who supplied stories for the publication. Thackeray was a great admirer of Cruikshank: "He has told a thousand truths in as many strange and fascinating ways; he has given a thousand new and pleasant thoughts to millions of people; he has never used his wit dishonestly."

Cruikshank was asked by the publisher, John Macrone, to illustrate a series of stories and articles by Charles Dickens, that had appeared in the Morning Chronicle. Macrone offered Dickens £100 for the copyright of these stories. Dickens accepted the proposal as it would provide an extra income just before his marriage. Dickens later recalled: "These Sketches were written and published, one by one, when I was a very young man. They were collected and republished while I was still a very young man; and sent into the world with all their imperfections... They comprise my first attempts at authorship... I am conscious of their often being extremely crude and ill-considered, and bearing obvious marks of haste and inexperience."

Peter Ackroyd has argued that Cruikshank was not an easy man to work with: "It was something of a coup for Macrone to enlist the services of this illustrator, George Cruikshank, in the cause of a young author of only modest fame. To have his name on the title page was, if not a guarantee of success, at least a provident hedge against failure... He was already very well known as a caricaturist and illustrator of books - he was in some ways a difficult man, with powerful perceptions but equally powerful opinions. He could be truculent and assertive, even though this self-assertive manner often gave way, in his famous drinking bouts, to one of drunken clowning and gaiety."

Sketches by Boz was published on 8th February 1836. In the introduction Dickens praised the drawings of Cruikshank: "Entertaining no inconsiderable feeling of trepidation, at the idea of making so perilous a voyage in so frail a machine, alone and unaccompanied, the author was naturally desirous to secure the assistance and companionship of some well-known individual, who had frequently contributed to the success, though his well-known reputation rendered it impossible for him ever to have shared the hazard, of similar undertakings."

Robert L. Patten has pointed out: "As over the next year they worked together on two series of Sketches by Boz... the relationship warmed from wary professionalism to bibulous bonhomie, interrupted by an occasional outburst of temper, of which each collaborator had his share. These volumes were a great success, both on account of Dickens's rising popularity and because Cruikshank's plates introduced deft and spirited graphic commentaries on the text and the town." Charles Dickens wrote to John Macrone saying he found Cruikshank difficult to work with and stated that "I have long believed Cruikshank to be mad."

(If you find this article useful, please feel free to share. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter)

George Hogarth, in the Morning Chronicle, described Dickens as "a close and acute observer of character and manners". However, Dickens was hurt by the numerous references to Cruikshank's talented drawings. The reviewer in The Sunday Herald admitted that after reading the book he was unsure "whether we most admire the racy humour and irresistible wit of the sketches, or of the illustrations in George Cruikshank's very best style".

1836 Richard Bentley had the idea of publishing a monthly journal in order to promote the novels he published. Bentley offered Dickens £500 for his next novel. Bentley also agreed to pay twenty guineas to Dickens in return for becoming editor of his journal, that he decided to to call Bentley's Miscellany. Bentley signed an agreement with Cruikshank to become the illustrator of Dickens's novel. He was paid £50 for the use of his name as illustrator and 12 guineas for every monthly etching.

The journal was first published in January 1837. The second edition included the first part of Dickens' novel, Oliver Twist. Each episode consisted of about 7,500 words. Most critics liked the series but Richard Harris Barham disliked the "radicalish tone" of the novel. The Spectator criticised Dickens's use in fiction of the "popular clamour against the New Poor Law". However, he did praise Dickens for his remarkable skill in making use of peculiarities of expression." Richard Ford, writing in the Quarterly Review , about the illustrations, described Cruikshank "as this man of undoubted genius".

Cruikshank continued to publish Cruikshank's Comic Almanack but his business was virtually destroyed by the arrival of Punch Magazine in 1841. John R. Harvey, the author of Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators (1970) has pointed out: "The independent satiric print was dying... Book-illustration was the only outlet for his talents, but in book-illustration he must sacrifice what mattered most in his vocation, his creative and moralizing independence. He did not give in, but fought all his life a fight which he must have known to be hopeless."

Cruikshank was commissioned by a Manchester reformer, Joseph Adshead in 1847, to produce The Bottle which sold almost 100,000 copies. Charles Dickens praised the work but argued that the consumption of beer, wine, and spirits should be understood as originating "in sorrow, or poverty, or ignorance". However, as Robert L. Patten pointed out: "For Dickens, a moderationist, social remedies, especially education and a living wage, would eliminate excess drinking; for Cruikshank, who knew from his own family the ravages of alcoholism, drinking was a destructive habit that could only be stopped by will-power. Indeed, once he had completed his graphic series, Cruikshank realized he ought to heed his own lesson and turn teetotal himself."

Cruikshank joined the Temperance Society and for the next thirty years he lectured to large audiences throughout the British Isles, on the evil effects of drink and the beneficial results of sobriety. Cruikshank also became involved in the movement to protect children and published several books on the subject including The Drunkard's Children (1848), A Slice of Bread and Butter (1857) and Our Gutter Children (1869).

John Ruskin offered to underwrite Cruikshank's illustrated autobiography. According to his biographer "Cruikshank laboured on his recollections until his death, going over and over the early years of his life and providing some glass etchings, many inconsequential, but the text never got very far." Ruskin, who saw some of these illustrations, admitted that Cruikshank had lost the talent of his early years.

George Cruikshank, deeply in debt, died of a acute respiratory infection at his home, 263 Hampstead Road, on 1st February, 1878.

Primary Sources

(1) Peter Ackroyd, Dickens (1990)

It was something of a coup for Macrone to enlist the services of this illustrator, George Cruikshank, in the cause of a young author of only modest fame. To have his name on the title page was, if not a guarantee of success, at least a provident hedge against failure... He was already very well known as a caricaturist and illustrator of books - he was in some ways a difficult man, with powerful perceptions but equally powerful opinions. He could be truculent and assertive, even though this self-assertive manner often gave way, in his famous drinking bouts, to one of drunken clowning and gaiety.

(2) John R. Harvey, Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators (1970)

The independent satiric print was dying... Book-illustration was the only outlet for his talents, but in book-illustration he must sacrifice what mattered most in his vocation, his creative and moralizing independence. He did not give in, but fought all his life a fight which he must have known to be hopeless. We see the fighting in the various abortive magazines he launched; each one failed. we see the fighting too in the insistent desire to play the leading role in the serial novels he illustrated: he claimed in later years that he had originated Oliver Twist and many novels by Ainsworth. Cruikshank's desire to usurp his novelists is well-known as an aberrant nuisance... far from being simply a function of his conceit and eccentricity, this desire is understandable and deserving of sympathy. Everyone said he was the new Hogarth, and he must surely have felt he had the right to be not less than an equal in any collaboration.