Robert Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool

Robert Jenkinson, the eldest son of the first Earl of Liverpool, was born on 7th June, 1770. He was educated at Charterhouse and Christ Church, Cambridge. At the age of twenty Robert was granted the seat of Appleby, a pocket borough owned by Sir James Lowther. Robert Jenkinson was a Tory and in May 1793, he spoke against Earl Grey's attempt to introduce parliamentary reform.

In February 1801, the Prime Minister, Viscount Sidmouth, promoted Jenkinson to the cabinet. Two years later Sidmouth granted Jenkinson the title Lord Hawkesbury in November 1803. When William Pitt replaced Sidmouth as Prime Minister in 1804, Jenkinson became leader of the government in the House of Lords.

On the death of his father in December, 1808, Jenkinson became the second Earl of Liverpool. When Spencer Perceval became prime minister in 1809 he appointed Lord Liverpool as secretary of war and the colonies. Perceval was assassinated in 1812, by a deranged bankrupt who blamed the government for his troubles, and Lord Liverpool was asked to become Britain's new prime minister.

Lord Liverpool was to remain in office for fifteen years. At first Liverpool was a popular prime minister. In 1815 British forces were victorious at the Battle of Waterloo. The abdication of Napoleon and the successful conclusion of the French Wars improved the public standing of Lord Liverpool's government. It was hoped that with the end of the conflict in Europe Lord Liverpool's government would be able to concentrate on introducing the social reforms that were much needed in Britain.

Liverpool disagreed with those who advocated reform. He reacted to the growth in the radical press by increasing the tax on newspapers. Radical journalists such as Robert Carlile and Henry Hetherington, responded by campaigning for an end to all taxes on knowledge.

In 1817 Britain endured an economic recession. Unemployment, a bad harvest and high prices produced riots, demonstrations and a growth in the Hampden Club movement. Lord Liverpool's government reacted by suspending Habeas Corpus for two years.

The economic situation gradually improved and Liverpool hoped that a reduction in taxation would prevent a revival of radicalism when the suspension of Habeas Corpus came to an end in 1818. This was not the case, and the summer of 1819 saw a series of large gatherings in favour of parliamentary reform, culminating in the massive public meeting at Manchester on 16th August 1819.

Lord Liverpool made it clear that he fully supported the action of the magistrates and the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry. Radicals reacted by calling what happened in St. Peter's Fields, the Peterloo Massacre, therefore highlighting the fact that Liverpool's government was now willing to use the same tactics against the British people that it had used against Napoleon and the French Army.

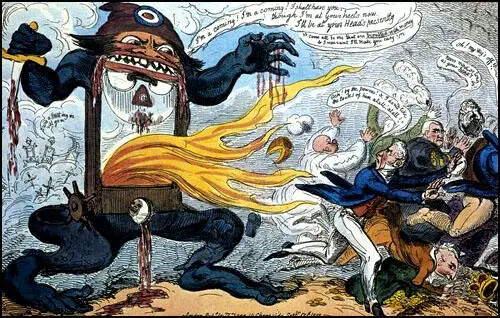

George Cruikshank criticised Liverpool's attitude towards reform with his cartoon entitled A Radical Reformer, A Neck or Nothing Man! Dedicated to the Heads of the Nation. It showed a flame-belching, guillotine monster wearing the cap associated with French revolutionaries, which is terrorising Britain's leaders. "I'm a coming! I'm a coming! he says, I shall have you - though I'm at your heels now, I'll be at your Heads presently. Come all to me that are troubled with money & I warrant I'll make you easy!!" On the right Lord Liverpool falls over a bag of money.

Liverpool's government decided to take action to prevent further large meetings demanding social reform. In November 1819 Parliament was assembled and it quickly passed the Six Acts. The main objective of this legislation was the "curbing radical journals and meeting as well as the danger of armed insurrection". (i) Training Prevention Act: A measure which made any person attending a gathering for the purpose of training or drilling liable to arrest. People found guilty of this offence could be transported for seven years. (ii) Seizure of Arms Act: A measure that gave power to local magistrates to search any property or person for arms. (iii) Seditious Meetings Prevention Act: A measure which prohibited the holding of public meetings of more than fifty people without the consent of a sheriff or magistrate. (iv) The Misdemeanours Act: A measure that attempted to reduce the delay in the administration of justice. (v) The Basphemous and Seditious Libels Act: A measure which provided much stronger punishments, including banishment for publications judged to be blasphemous or seditious. (vi) Newspaper and Stamp Duties Act: A measure which subjected certain radical publications which had previously avoided stamp duty by publishing opinion and not news, to such duty.

Francis Place, one of the leaders of the reform movement, wrote that "I despair of being able adequately to express correct ideas of the singular baseness, the detestable infamy, of their equally mean and murderous conduct. They who passed the Gagging Acts in 1817 and the Six Acts in 1819 were such miscreants, they could they have acted thus in a well-ordered community they would all have been hanged."

In 1822 Liverpool used similar methods to deal with the distress and disaffection in Ireland. Liverpool found the heavy burden of running a divided country increasingly stressful. Liverpool began to suffer health problems and on 17th February, 1827, he had a stroke. Liverpool was forced to resign and although he lived for nearly two more years, he was rarely conscious.

Lord Liverpool died on 4th December, 1828.

Primary Sources

(1) Lord Liverpool wrote to George Canning on 23rd September, 1819.

The accounts of the proceedings at Manchester will of course have reached you, and will probably have in some degree alarmed you. You will naturally ask whether the proceedings of the magistrates at Manchester on the 16th were really justifiable? To this I answer, in the first instance, that all the papers on which they proceeded were laid before the Chancellor, and the Attorney and Solicitor-General, and that they were fully satisfied that the meeting was of a character and description, and assembled under such circumstances, as justified the magistrates in dispersing it by force.

When I say that the proceedings of the magistrates at Manchester on the 16th were justifiable, you will understand me as not by any means deciding that the course which they pursued on that occasion was in all its parts prudent. A great deal might be said in their favour even on this; but, whatever judgment might be formed in this respect, being satisfied that they were substantially right, there remained no alternative but to support them; and I am sorry to say that, notwithstanding the support which they have received, there prevails such a panic throughout that part of the country that it is difficult to get either magistrates to act or witnesses to come forward to give evidence, and that many of the lower orders who were supposed loyal have joined the disaffected, partly from fear, and partly from a conviction that some great change was at hand.