Spencer Perceval

Spencer Perceval, the son of the 2nd Earl of Egmont, was born in 1762. After being educated at Harrow and Trinity College, Cambridge, he became a lawyer.

In 1796 Perceval was elected MP for Northampton. In the House of Commons Perceval became a strong supporter of William Pitt and the Tory group in Parliament. When Henry Addington became Prime Minister in 1801 he appointed Perceval as his solicitor-general. The following year he was promoted to attorney-general.

When William Cavendish-Bentinck, Duke of Portland became Prime Minister in 1807 he appointed Perceval as his Chancellor of the Exchequer. Perceval got on well with George III and loyally supported the king's opposition to Catholic Emancipation.

When Portland died in 1809, Spencer Perceval accepted the king offer to become Prime Minister. Perceval's period of power coincided with an economic depression and considerable industrial unrest. This resulted in his government introducing repressive methods against the Luddites. This included the Frame-Breaking Act which made the destruction of machines a capital offence.

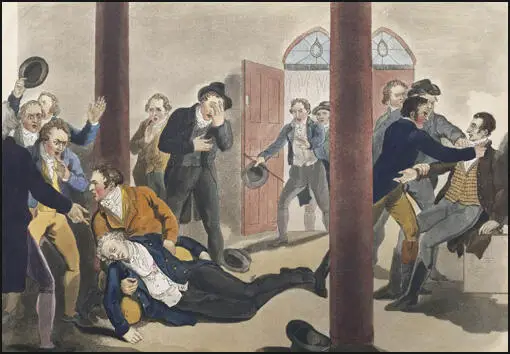

Perceval held the post until 1812 when he became the only British Prime Minister in history to be assassinated. Spencer Perceval was shot when entering the lobby of the House of Commons by John Bellingham, a failed businessman from Liverpool. Bellingham, who blamed Perceval for his financial difficulties, was later hanged for his crime.

Primary Sources

(1) After Spencer Perceval's assassination in 1812, Stuart Wortley, made a speech in the House of Commons about the former Prime Minister (21st May, 1812)

Mr. Perceval had great talents. He was anxious to see an administration formed upon a liberal basis, calculated to comprehend the talents and influences of the country, and to promote its security and honour.

(2) Archibald Prentice, wrote about the Luddite disturbances in April 1812, in his book Historical Sketches and Personal Recollections of Manchester.

On Saturday, the 18th April, a numerous body of women, chiefly women, assembled at the potato market, Shude Hill, where the sellers were asking 14s. and 15s. per load (252 lbs.) for potatoes. Some of the women began forcibly to take possession of the articles; but the civil and military power interposing, to fix a sort of maximum, for eight shillings per load, at which they were sold in small portions. On Monday a cart carrying fourteen loads of meal was stopped, and the meal carried away. On 27th April a riotous assembly took place at Middleton. The weaving factory of Mr. Burton and Sons had been previously threatened in consequence of their mode of weaving being done by the operation of steam. The factory was protected by soldiers, so strongly as to be impregnable to their assault; they then flew to the house of Mr. Emanuel Burton, where they wreaked their vengeance by setting it on fire. On Friday, the 24th April, a large body of weavers and mechanics began to assemble about midday, with the avowed intention of destroying the power-looms, together with the whole of the premises, at Westhoughton. The military rode at full speed to Westhoughton; and on their arrival were surprised to find that the premises were entirely destroyed, while not an individual could be seen to whom attached any suspicion of having acted a part in this truly dreadful outrage.

(3) Lord Byron, speech in the House of Lords (27th February, 1812)

During the short time I recently passed in Nottingham, not twelve hours elapsed without some fresh act of violence; and on that day I left the the county I was informed that forty Frames had been broken the preceding evening, as usual, without resistance and without detection.

Such was the state of that county, and such I have reason to believe it to be at this moment. But whilst these outrages must be admitted to exist to an alarming extent, it cannot be denied that they have arisen from circumstances of the most unparalleled distress: the perseverance of these miserable men in their proceedings, tends to prove that nothing but absolute want could have driven a large, and once honest and industrious, body of the people, into the commission of excesses so hazardous to themselves, their families, and the community.

They were not ashamed to beg, but there was none to relieve them: their own means of subsistence were cut off, all other employment preoccupied; and their excesses, however to be deplored and condemned, can hardly be subject to surprise.

As the sword is the worst argument than can be used, so should it be the last. In this instance it has been the first; but providentially as yet only in the scabbard. The present measure will, indeed, pluck it from the sheath; yet had proper meetings been held in the earlier stages of these riots, had the grievances of these men and their masters (for they also had their grievances) been fairly weighed and justly examined, I do think that means might have been devised to restore these workmen to their avocations, and tranquillity to the country.

(4) Colonel Fletcher of Bolton was shocked by how people in his town responded to the death of Spencer Perceval.

The people expressed joy at the news. A man came running down the street, leaping in the air, waving his hate round his head, and shouting with frantic joy, "Perceval is shot, hurrah! Perceval is shot, hurrah!"