Poor Man's Guardian

Henry Hetherington worked for Richard Carlile as a shopman before he began publishing the daily paper Penny Papers for the People in 1830. In the first edition published on 1st October, 1830, Hetherington explain his motives for publishing this paper: "It is the cause of the rabble we advocate, the poor, the suffering, the industrious, the productive classes. We will teach this rabble their power - we will teach them that they are your master, instead of being your slaves."

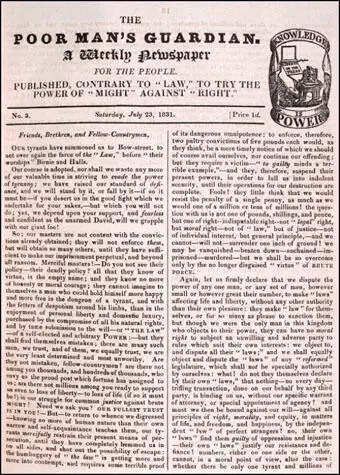

In July 1831 changed the name of his paper to the Poor Man's Guardian. Hetherington's refused to pay the 4d. stamp duty on each paper sold. On the front page, where the red spot of the stamp duty should have been, Hetherington printed the slogan "Knowledge is Power". Underneath were the words, "Published in Defiance of the Law, to try the Power of Right against Might".

The Poor Man's Guardian was closely associated with the National Union of the Working Classes, an organisation formed earlier that year by Hetherington and William Lovett to campaign for universal suffrage and trade union rights. Hetherington gave extensive coverage to the struggle over the 1832 Reform Act and was deeply disappointed by the refusal of Parliament to give the vote to working men.

Henry Hetherington toured Britain giving speeches on parliamentary reform and recruiting agents to sell the Poor Man's Guardian. By 1833 circulation had reached 22,000, with two-thirds of the copies being sold in the provinces. In a three year period, twenty-five of these forty agents went to prison for selling an unstamped newspaper. One of those was arrested was George Julian Harney, who was imprisoned three times for selling the Poor Man's Guardian. Later Harney was to become the editor of the very successful Chartist newspaper, The Northern Star.

Hetherington was also imprisoned for two periods of six months and in November 1832, he was replaced as editor by James Bronterre O'Brien. The new editor had been influenced by European socialist writers such as Gracchus Babeuf and began publishing translations of their work in the Poor Man's Guardian. O'Brien argued that workers in other countries were also involved in a struggle for universal suffrage. In October 1834 he wrote: "The history of mankind shows that from the beginning of the world, the rich of all countries have been in a permanent state of conspiracy to keep down the poor of all countries, and for this plain reason - because the poverty of the poor man is essential to the riches of the rich man. The desire of one man to live on the fruits of another's labour is the original sin of the world."

Although the Poor Man's Guardian gave its support to the trade union movement it constantly argued that the real struggle was for universal suffrage. As it pointed out on many occasions, if working men were not represented in the House of Commons, gains made by the trade unions could always be undermined by legislation passed by Parliament.

The campaign for an untaxed press obtained a boast in June 1834 when it was ruled that the Poor Man's Guardian was not an illegal publication. The newspaper reported: "After all the badgerings of the last three years - after all the fines and incarcerations - after all the spying and blood-money, the Poor Man's Guardian was pronounced, on Tuesday by the Court of Exchequer (and by a Special Jury too) to be a perfectly legal publication." As a result of this court ruling, Henry Hetherington invested in a new printing press, the Napier double-cylinder, a machine capable of printing 2,500 copies an hour.

In 1835 the two leading unstamped radical newspapers, the Poor Man's Guardian, and The Police Gazette, were selling more copies in a day than The Times sold all week. It was estimated at the time that the circulation of leading six unstamped newspapers had now reached 200,000.

The authorities continued to try and stop the newspaper being sold. In 1835 Joseph Swann was sentenced to four and a half years for selling The Poor Man's Guardian. During the trial he explained his actions. Well, sir, I have been out of employment for some time; neither can I obtain work; my family are all starving... And for another reason, the weightiest of all; I sell them for the good of my fellow countrymen; to let them see how they are misrepresented in parliament... I wish every man to read those publications."

In 1835 the offices of the newspaper were raided. Hetherington's stock and equipment, including his new Napier printing machine, was seized and destroyed. For a while Henry Hetherington printed the Poor Man's Guardian on borrowed equipment but in December, 1835, he decided to cease publication.

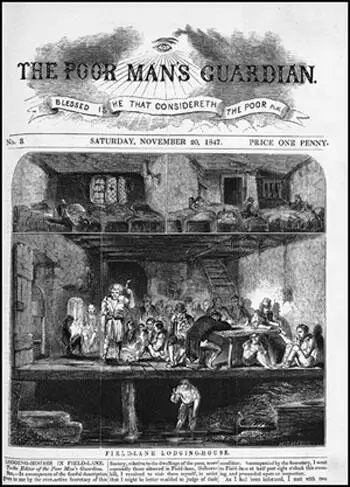

In 1847 there was a brief attempt to start publishing The Poor Man's Guardian again. Despite the use of engravings the newspaper only lasted for a few weeks.

Primary Sources

(1) The Poor Man's Guardian (July, 1831)

Defiance is our only remedy; we cannot be a slave in all; we submit to much - for it is impossible to be wholly consistent - but we will try the power of Right against Might; we will begin by protesting and upholding this grand bulwark of all our liberties - the Freedom of the Press - the Press, too, of the ignorant and the Poor. we have taken upon ourselves its protection, and we will never abandon our post: we will die rather.

(2) The Poor Man's Guardian (24th September, 1831)

We, the Poor Man's Guardian, proclaim that we represent the working, productive, and useful but poor classes, who constitute a very great majority of the population of Great Britain. We proclaim that some hundreds of thousands of the poor have elected us the GUARDIAN of their rights and liberties.

(3) The Poor Man's Guardian (29th April, 1832)

To talk of representation, in any shape, being of any use to the people is sheer nonsense, unless the people have a House of working men, and represent themselves. Those who make the laws now, and are intended, by the reform bill, to make them in future all live by profits of some sort or another. They will, therefore, no matter who elect them,or how often they are elected, always make the laws to raise profits and keep down the price of labour.

(4) The Poor Man's Guardian (July, 1831)

The promoters of the Reform Bill projected it, not with a view to subvert, or even remodel, our aristocratic institutions, but to consolidate them by a reinforcement of sub-aristocracy from the middle-classes.

(5) Letter published in the last edition of the Poor Man's Guardian (26th December, 1831)

I am, with many more of my friends and brother Radicals, sorry to hear that the Poor Man's Guardian is to be continued no longer. It has been my leading star, and I have no doubt of hundreds more like me. I hope and trust that when the name and fame of such men as the bloodstained hero of Waterloo shall be sunk in oblivion, or only thought of with contempt, the name of the Editor of the Poor Man's Guardian will be celebrated with songs of joy. That you may meet with success in your next undertaking, is the sincere wish of a working man.

(6) In 1835 Joseph Swann was sentenced to four and a half years for selling The Poor Man's Guardian. During the trial he explained his actions.

Well, sir, I have been out of employment for some time; neither can I obtain work; my family are all starving... And for another reason, the weightiest of all; I sell them for the good of my fellow countrymen; to let them see how they are misrepresented in parliament... I wish every man to read those publications.