London Corresponding Society

In January 1792 a group of four men, including Thomas Hardy, a London shoemaker, began meeting to discuss the possibility of forming a group of working men in order to campaign for the vote. On the 25th January 1792 they held a public meeting on parliamentary reform. Only eight people attended but the men decided to form a group called the London Corresponding Society. Early members included John Thelwall, John Horne Tooke, Joseph Gerrald, Olaudah Equiano and Maurice Margarot.

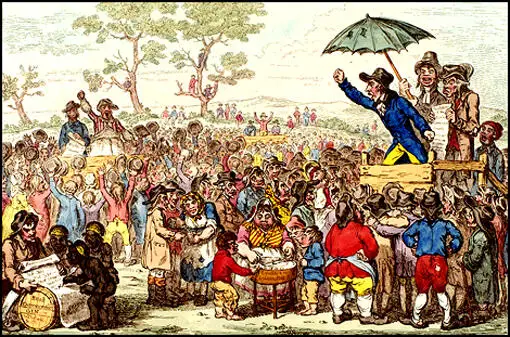

As well as campaigning for the vote, the strategy was to create links with other reforming groups in Britain. Thomas Hardy was appointed as treasurer and secretary of the organisation. The society passed a series of resolutions and after being printed on handbills, they were distributed to the public. These resolutions also included statements attacking the government's foreign policy. A petition was started and by May 1793, 6,000 members of the public had signed saying they supported the resolutions of the London Corresponding Society.

By the summer of 1793 the London Corresponding Society had made contact with parliamentary reform groups in Manchester, Sheffield, Nottingham, Derby, Stockport and Tewksbury. They also had meetings with the Society for Constitutional Information, an organisation formed by Major John Cartwright. At the end of 1793 Thomas Muir and the supporters of parliamentary reform in Scotland began to organise a convention in Edinburgh. The Society sent two delegates Joseph Gerrald and Maurice Maragot, but the men and other leaders of the convention were arrested and tried for sedition. Several of the men, including Gerrald and Maragot, were sentenced to fourteen years transportation.

The reformers were determined not to be beaten and Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall began to organise another convention. When the authorities heard what was happening, Hardy and the other two men were arrested and committed to the Tower of London and charged with high treason. The men's trial began at the Old Bailey on 28th October, 1794. The prosecution, led by Lord Eldon, argued that the leaders of the London Corresponding Society were guilty of treason as they organised meetings where people were encouraged to disobey King and Parliament. However, the prosecution was unable to provide any evidence that Hardy and his co-defendants had attempted to do this and the jury returned a verdict of "Not Guilty".

The government continued to persecute supporters of parliamentary reform. Habeas Corpus was suspended in 1794, enabling the government to detain prisoners without trial. In 1797 Samuel Romilly successfully defended John Binns, against a charge of seditious words.

The Seditious Meetings Act made the organisation of parliamentary reform gatherings extremely difficult. Finally, in 1799, the government persuaded Parliament to pass a Corresponding Societies Act. It was now illegal for the London Corresponding Society to meet and the organisation came to an end.

Primary Sources

(1) Resolutions passed by the London Corresponding Society in January, 1793.

(I) That nothing but a fair, adequate and annually renovated representation in Parliament, can ensure the freedom of this country.

(II) That we are fully convinced, a thorough Parliamentary Reform, would remove every grievance under which we labour.

(III) That we will never give up the pursuit of such Parliamentary Reform.

(IV) That if it be a part of the power of the king to declare war when and against whom he pleases, we are convinced that such power must have been granted to him under the condition, that he should ever be subservient to the national advantage.

(V) That the present war against France, and the existing alliance with the Germantic Powers, so far as it relates to the prosecution of that war, has hitherto produced, and is likely to produce nothing but national calamity, if not utter ruin.

(VI) That it appears to us that the wars in which Great Britain has engaged, within the last hundred years, have cost her upwards of three hundred and seventy million! not to mention the private misery occasioned thereby, or the lives sacrificed.

(VII) That we are persuaded the majority, if not the whole of those wars, originated in Cabinet intrigue, rather than absolute necessity.

(VIII) That every nation has an unalienable right to choose the mode in which it will be governed, and that it is an act of tyranny and oppression in any other nation to interfere with, or attempt to control their choice.

(IX) That peace being the greatest blessing, ought to be sought most diligently by every wise government.

(X) That we do exhort every well wisher to this country, not to delay in improving himself in constitutional knowledge.

(2) The secretary of the Tewksbury Corresponding Society sent a letter to Thomas Hardy in July, 1794.

The burning of Thomas Paine's effigy, together with the effects of the present war, has done more good to the cause than the most substantial arguments for universal suffrage.

(3) Lord Braxfield explained why he had to sentence Thomas Muir and the other leaders of the Convention in Edinburgh to be transported to Australia for fourteen years.

The British constitution is the best that ever was since the creation of the world, and it is not possible to make it better. Yet Mr. Muir has gone among the ignorant country people and told them Parliamentary Reform was absolutely necessary for preserving their liberty.