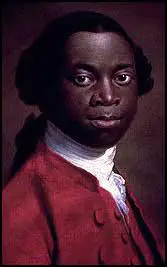

Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano was born in Essaka, an Igbo village in the kingdom of Benin (now Nigeria) in 1745. His father was one of the province's elders who decided disputes. According to James Walvin "Equiano described his father as a local Igbo eminence and slave owner".

When he was about eleven, Equiano was kidnapped and after six months of captivity he was brought to the coast where he encountered white men for the first time. Equiano later recalled in his autobiography, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1787): "The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast, was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror, when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled, and tossed up to see if I were sound, by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me. Their complexions, too, differing so much from ours, their long hair, and the language they spoke, (which was very different from any I had ever heard) united to confirm me in this belief. Indeed, such were the horrors of my views and fears at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own, I would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest slave in my own country."

Olaudah Equiano was placed on a slave-ship bound for Barbados. "I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a greeting in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life; so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and, on my refusing to eat, one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across, I think, the windlass, and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. The air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died. The wretched situation was again aggravated by the chains, now unsupportable, and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable."

After a two-week stay in the West Indies Equiano was sent to the English colony of Virginia. In 1754 he was purchased by Captain Henry Pascal, a British naval officer. He was given the new name of Gustavus Vassa and was brought back to England. According to his biographer, James Walvin: "For seven years he served on British ships as Pascal's slave, participating in or witnessing several battles of the Seven Years' War. Fellow sailors taught him to read and write and to understand mathematics. He was also converted to Christianity, reading the Bible regularly on board ship. Baptized at St Margaret's Church, Westminster, on 9 February 1759, he struggled with his faith until finally opting for Methodism."

By the end of the Seven Years' War he reached the rank of able seaman. Although he was freed by Pascal he was re-enslaved in London in 1762 and shipped to the West Indies. For four years he worked for a Montserrat based merchant, sailing between the islands and North America. "I was often a witness to cruelties of every kind, which were exercised on my unhappy fellow slaves. I used frequently to have different cargoes of new Negroes in my care for sale; and it was almost a constant practice with our clerks, and other whites, to commit violent depredations on the chastity of the female slaves; and these I was, though with reluctance, obliged to submit to at all times, being unable to help them." James Walvin points out that "Equiano... also trading to his own advantage as he did so. Ever alert to commercial openings, Equiano accumulated cash and in 1766 bought his own freedom."

Equiano now worked closely with Granvile Sharpe and Thomas Clarkson in the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Equiano spoke at a large number of public meetings where he described the cruelty of the slave trade. In 1787 Equiano helped his friend, Offobah Cugoano, to published an account of his experiences, Narrative of the Enslavement of a Native of America. Copies of his book was sent to George III and leading politicians. He failed to persuade the king to change his opinions and like other members of the royal family remained against abolition of the slave trade.

Equiano published his own autobiography, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African in 1789. He travelled throughout England promoting the book. It became a bestseller and was also published in Germany (1790), America (1791) and Holland (1791). He also spent over eight months in Ireland where he made several speeches on the evils of the slave trade. While he was there he sold over 1,900 copies of his book.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

David Dabydeen has argued: "With Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce and Granville Sharpe, Equiano was a major abolitionist, working ceaselessly to expose the nature of the shameful trade. He travelled throughout Britain with copies of his book, and thousands upon thousands attended his readings. When John Wesley lay dying, it was Equiano's book he took up to reread."

On 7th April 1792 Equiano married Susanna Cullen (1761-1796) of Soham, Cambridgeshire. The couple had two children, Anna Maria (16th October 1793) and Johanna (11th April 1795). However, Anna Maria died when she was only four years old. Equiano's wife died soon afterwards. During this period he was a close friend of Thomas Hardy, secretary of the London Corresponding Society. Equiano became an active member of this group that campaigned in favour of universal suffrage.

Olaudah Equiano was appointed to the expedition to settle former black slaves in Sierra Leone, on the west coast of Africa. However, he died at his home at Paddington Street, Marylebone, on 31st March, 1797 before he could complete the task.

The historian, James Walvin, has argued: "After his death his book was anthologized by abolitionists (especially before the American Civil War). Thereafter, however, Equiano was virtually forgotten for a century. In the 1960s his autobiography was rediscovered and reissued by Africanist scholars; various editions of his Narrative have since sold in large numbers in Britain, North America, and Africa. Equiano's autobiography remains a classic text of an African's experiences in the era of Atlantic slavery. It is a book which operates on a number of levels: it is the diary of a soul, the story of an autodidact, and a personal attack on slavery and the slave trade. It is also the foundation-stone of the subsequent genre of black writing; a personal testimony which, however mediated by his transformation into an educated Christian, remains the classic statement of African remembrance in the years of Atlantic slavery." Chinua Achebe has called him "the father of African literature" whereas Henry Louis Gates claimed him for America as "the founding father of the Afro-American literary tradition".

In 2005 Vincent Carretta published his book, Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-made Man. He argued that he had found a document that suggests that Equiano was really born in South Carolina. As David Dabydeen points out: "In other words, Equiano may never have set foot in Africa, never mind boarded a slave ship, and the narrative of his early life may be pure fiction." However, he adds: "Equiano's autobiography, Carretta suggests, is a monumental 18th-century text, a unique mixture of travel-writing, sea lore, sermon, economic tract and fiction. That the early chapters may have invented a life in Africa only adds to our appreciation of Equiano's imaginative depth and literary talent."

Primary Sources

(1) Olaudah Equiano, letter to Gordon Turnbull after the publication of his book Apology for Negro Slavery, in the Public Advertiser published on 5th February, 1788.

To kidnap our fellow creatures, however they may differ in complexion, to degrade them into beasts of burthen, to deny them every right but those, and scarcely those we allow to a horse, to keep them in perpetual servitude, is a crime as unjustifiable as cruel; but to avow and to defend this infamous traffic required the ability and the modesty of you and Mr. Tobin. Can any man be a Christian who asserts that one part of the human race were ordained to be in perpetual bondage to another.

(2) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

I was born, in the year 1745, in a charming fruitful vale, named Essaka. The distance of this province from the capital of Benin and the sea coast must be very considerable; for I had never heard of white men or Europeans, nor of the sea.

The dress of both sexes is nearly the same. It generally consists of a long piece of calico, or muslin, wrapped loosely round the body, somewhat in the form of a highland plaid. This is usually dyed blue, which is our favourite colour. It is extracted from a berry, and is brighter and richer than any I have seen in Europe. Besides this, our women of distinction wear golden ornaments; which they dispose with some profusion on their arms and legs. When our women are not employed with the men in tillage, their usual occupation is spinning and weaving cotton, which they afterwards dye, and make it into garments. They also manufacture earthen vessels, of which we have many kinds.

(3) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

Generally, when the grown people in the neighbourhood were gone far in the fields to labour, the children assembled together in some of the neighborhood's premises to play; and commonly some of us used to get up a tree to look out for any assailant, or kidnapper, that might come upon us; for they sometimes took those opportunities of our parents' absence, to attack and carry off as many as they could seize.

One day, when all our people were gone out to their works as usual, and only I and my dear sister were left to mind the house, two men and a woman got over our walls, and in a moment seized us both; and, without giving us time to cry out, or make resistance, they stopped our mouths, and ran off with us into the nearest wood. Here they tied our hands, and continued to carry us as far as they could, till night came on, when we reached a small house, where the robbers halted for refreshment, and spent the night. We were then unbound; but were unable to take any food; and, being quite overpowered by fatigue and grief, our only relief was some sleep, which allayed our misfortune for a short time.

(4) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast, was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror, when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled, and tossed up to see if I were sound, by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me.

Their complexions, too, differing so much from ours, their long hair, and the language they spoke, (which was very different from any I had ever heard) united to confirm me in this belief. Indeed, such were the horrors of my views and fears at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own, I would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest slave in my own country.

When I looked round the ship too, and saw a large furnace of copper boiling, and a multitude of black people of every description chained together, every one of their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate; and, quite overpowered with horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck and fainted. When I recovered a little, I found some black people about me, who I believed were some of those who had brought me on board, and had been receiving their pay; they talked to me in order to cheer me, but all in vain. I asked them if we were not to be eaten by those white men with horrible looks, red faces, and long hair. They told me I was not: and one of the crew brought me a small portion of spirituous liquor in a wine glass, but, being afraid of him, I would not take it out of his hand. One of the blacks, therefore, took it from him and gave it to me, and I took a little down my palate, which, instead of reviving me, as they thought it would, throw me into the greatest consternation at the strange feeling it produced, having never tasted any such liquor before. Soon after this, the blacks who brought me on board went off, and left me abandoned to despair.

(5) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a greeting in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life; so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and, on my refusing to eat, one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across, I think, the windlass, and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely.

The white people looked and acted, as I thought, in so savage a manner; for I had never seen among my people such instances of brutal cruelty. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us.

The air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died. The wretched situation was again aggravated by the chains, now unsupportable, and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable.

(6) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

At last, we came in sight of the island of Barbados, at which the whites on board gave a great shout, and made many signs of joy to us. We did not know what to think of this; but as the vessel drew nearer, we plainly saw the harbor, and other ships of different kinds and sizes, and we soon anchored amongst them, off Bridgetown.

Many merchants and planters now came on board, though it was in the evening. They put us in separate parcels, and examined us attentively. They also made us jump, and pointed to the land, signifying we were to go there. We thought by this, we should be eaten by these ugly men, as they appeared to us; and, when soon after we were all put down under the deck again, there was much dread and trembling among us, and nothing but bitter cries to be heard all the night from these apprehensions, insomuch, that at last the white people got some old slaves from the land to pacify us. They told us we were not to be eaten, but to work, and were soon to go on land, where we should see many of our country people. This report eased us much. And sure enough, soon after we were landed, there came to us Africans of all languages.

(7) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

We were conducted immediately to the merchant's yard, where we were all pent up together, like so many sheep in a fold, without regard to sex or age. As every object was new to me, every thing I saw filled me with surprise. What struck me first, was, that the houses were built with bricks and stories, and in every other respect different from those I had seen in Africa; but I was still more astonished on seeing people on horseback. I did not know what this could mean; and, indeed, I thought these people were full of nothing but magical arts.

(8) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

We were not many days in the merchant's custody, before we were sold after their usual manner, which is this: On a signal given, (as the beat of a drum) the buyers rush at once into the yard where the slaves are confined, and make choice of that parcel they like best. The noise and clamor with which this is attended, and the eagerness visible in the countenances of the buyers, serve not a little to increase the apprehension of terrified Africans, who may well be supposed to consider them as the ministers of that destruction to which they think themselves devoted.

In this manner, without scruple, are relations and friends separated, most of them never to see each other again. I remember, in the vessel in which I was brought over, in the men's apartment, there were several brothers, who, in the sale, were sold in different lots; and it was very moving on this occasion, to see and hear their cries at parting. Is it not enough that we are torn from our country and friends, to toil for your luxury and lust of gain? Must every tender feeling be likewise sacrificed to your avarice? Are the dearest friends and relations, now rendered more dear by their separation from their kindred, still to be parted from each other, and thus prevented from cheering the gloom of slavery, with the small comfort of being together; and mingling their sufferings and sorrows? Why are parents to lose their children, brothers their sisters, husbands their wives? Surely, this is a new refinement in cruelty, which, while it has no advantage to atone for it, thus aggravates distress; and adds fresh horrors even to the wretchedness of slavery.

(9) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

While I was thus employed by my master, I was often a witness to cruelties of every kind, which were exercised on my unhappy fellow slaves. I used frequently to have different cargoes of new Negroes in my care for sale; and it was almost a constant practice with our clerks, and other whites, to commit violent depredations on the chastity of the female slaves; and these I was, though with reluctance, obliged to submit to at all times, being unable to help them. When we have had some of these slaves on board my master's vessels, to carry them to other islands, or to America, I have known our mates to commit these acts most shamefully, to the disgrace, not of Christians only, but of men. I have even known them to gratify their brutal passion with females not ten years old; and these abominations, some of them practised to such scandalous excess, that one of our captains discharged the mate and others on that account. And yet in Montserrat I have seen a Negro man staked to the ground, and cut most shockingly, and then his ears cut off bit by bit, because he had been connected with a white woman, who was a common prostitute. As if it were no crime in the whites to rob an innocent African girl of her virtue, but most heinous in a black man only to gratify a passion of nature, where the temptation was offered by one of a different color, though the most abandoned woman of her species.

(10) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

One man told me that he had sold 41,000 negroes, and that he once cut of a negro man's leg for running away. I told him that the Christian doctrine taught us to do unto others as we would that others should do unto us. He then said that his scheme had the desired effect - it cured that man and some others of running away.

Another negro man was half hanged, and then burnt, for attempting to poison a cruel overseer. Thus, by repeated cruelties, are the wretched first urged to despair, and then murdered, because they still retain so much of human nature about them as to wish to put an end to their misery, and retaliate on their tyrants. These overseers are indeed for the most part persons of the worst character of any denomination of men in the West Indies. Unfortunately, many humane gentlemen, but not residing on their estates, are obliged to leave the management of them in the hands of these human butchers, who cut and mangle the slaves in a shocking manner on the most trifling occasions, and altogether treat them in every respect like brutes.

(11) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

Their huts, which ought to be well covered, and the place dry where they take their little repose, are often open sheds, built in damp places; so that when the poor creatures return tired from the toils of the field, they contract many disorders, from being exposed to the damp air in this uncomfortable state, while they are heated, and their pores are open. This neglect certainly conspires with many others to cause a decrease in the births as well as in the lives of the grown negroes.

(12) Olaudah Equiano, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1789)

I knew one man in Montserrat whose slaves looked remarkably well, and never needed any fresh supplies of negroes; and there are many other estates, especially in Barbados, which, from such judicious treatment, need no fresh stock of negroes at any time. I have the honor of knowing a most worthy and humane gentleman, who is a native of Barbados, and has estates there. He allows them two hours of refreshment at mid-day, and many other indulgencies and comforts, particularly in their lodging; and, besides this, he raises more provisions on his estate than they can destroy; so that by these attentions he saves the lives of his negroes, and keeps them healthy, and as happy as the condition of slavery can admit.

(13) David Dabydeen, The Guardian (3rd December 2005)

When Olaudah Equiano published his autobiography in England in 1789, he achieved instant celebrity. Several thousand copies were sold, the subscribers including the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York and the Duke of Cumberland. The book went through nine editions between 1789 and 1794, and pirated versions appeared in Holland, New York, Russia and Germany. He was a best-selling author, and became the wealthiest black man in the English-speaking world. He was so well off that he dabbled in moneylending to English people. His daughter inherited £950 and a silver watch from his estate....

A major reason for Equiano's popularity is that his autobiography contains a detailed account of his birth and childhood in Nigeria, with rare descriptions of the culture of 18th-century Igbo society. His narrative of the Atlantic crossing in a slave ship is as unique as it is moving. The early chapters are much anthologised since they offer a first-hand record of an African kidnapped at the age of ten, taken to the coast, sold to European merchants and despatched to the Americas.

Equiano writes passionately and vividly of his separation from his mother and sister, of his initial horror at seeing Europeans (they behaved so brutishly and were so alien to behold - "white men with horrible looks, red faces and long hair" - that he feared they were cannibals bent on eating the cargo of slaves), of the astonishment of seeing a ship for the first time and, on the transatlantic journey, of the strange and exotic sight of flying fish and other sea creatures. In the midst of dreadful suffering the child-Equiano asserts the magical beauty of life. A sympathetic white sailor lets him look through a quadrant. "The clouds appeared to me to be land, which disappeared as they past along. This heightened my wonder and I was now more persuaded than ever that I was in another world, and that everything about me was magic."

Fascinating and bestselling material, but how truthful? Vincent Carretta's biography seems to have torpedoed the slave ship and shattered trust in Equiano's veracity. Through years of patient and tenacious research in neglected archives, Carretta has discovered not one but two documents indicating that Equiano was born in Carolina - the first, a baptism record from February 9 1759, in St Margaret's Church, Westminster, stating that he was a "Black, born in Carolina, 12 years old"; the second, a muster list on a ship in which Equiano served in 1773, on which his birthplace is declared to be "South Carolina". In other words, Equiano may never have set foot in Africa, never mind boarded a slave ship, and the narrative of his early life may be pure fiction.

Needless to say, many scholars of African-American studies are furious with Carretta for seeming to suggest that Equiano is a trickster. One of them suggested he should have buried the evidence, for as one journalist in the Chronicle of Higher Education put it: "Carretta's conclusions threaten a pillar of scholarship on slave narratives and the African diaspora. Questioning Equiano's origins calls into doubt some fundamental assumptions made in departments of African-American Studies." Many Nigerians too are up in arms, Equiano being their star writer and witness. The fact that Carretta is white has increased the level of hostility to his book.

So how are we to reassess Equiano? Carretta himself suggests that his possible birth in Carolina rather than Africa in no way diminishes the power of his testimony. Autobiography, after all, is always partly fictional, the narrator excited by storytelling, by shaping and plotting the tale and by dressing up dull facts. Equiano was African in terms of origin, he knew the horrors of the slave trade which by the 1780s were widely broadcast by white abolitionists. What he did was to take it upon himself to write the first substantial account of slavery from an African viewpoint but, as importantly, to write it with pulse and heartbeat, giving passion to the subject so as to arouse sympathy and support for the cause of abolition. With Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce and Granville Sharpe, Equiano was a major abolitionist, working ceaselessly to expose the nature of the shameful trade. He travelled throughout Britain with copies of his book, and thousands upon thousands attended his readings. When John Wesley lay dying, it was Equiano's book he took up to reread.

Carretta's biography, far from detracting from Equiano's greatness, calls attention to it. Apart from the doubt about Equiano's birth, Carretta has tracked down records proving that practically everything else he told about his life was factually correct. Carretta reveals a man almost unique in his travelling and experience of different cultures and landscapes. Equiano worked on ships trading in the West Indies, North America, Central America and the Mediterranean. In 1773 he was an able seaman on the Phipps expedition to the North Pole - probably the first African to set foot on Arctic ice. And wherever he went he sought out the strangeness of the place, never allowing his status as an exploited black man to dim his sense of awe. Sailing to Philadelphia he is "surprised at the sight of some whales, having never seen any such large sea monsters before"; in Italy he witnesses an eruption of Mount Vesuvius - "it was extremely awful"; sighting Arctic ice he is moved by "the whole of this striking, grand and uncommon scene; and, to heighten it still more, the reflection of the sun from the ice gave the clouds a most beautiful appearance." Always he conveys the sense of a natural world of overpowering beauty, far removed from the sordid human world of slavery.

Equiano's autobiography, Carretta suggests, is a monumental 18th-century text, a unique mixture of travel-writing, sea lore, sermon, economic tract and fiction. That the early chapters may have invented a life in Africa only adds to our appreciation of Equiano's imaginative depth and literary talent. Carretta has done great service to the study of the African diaspora, unearthing more documentation on Equiano than any previous scholar, even locating the gravestone of Equiano's daughter, Joanna, in Abney Park Cemetery, North London. He deserves applause, not resentment, for his indefatigable research.