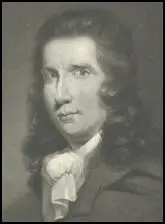

Joseph Gerrald

Joseph Gerrald, the son of a wealthy planter in the West Indies, was born in St. Christopher on 9th February 1763. At the age of two Joseph and his mother, Ann Gerrald, came to England. Anne Gerrald died soon after arriving and Joseph was sent to a boarding school in Hammersmith. Later he was transferred to the care of Dr. Samuel Parr at Stanmore School. After finishing his education Gerrald returned to the plantation in the West Indies that he had inherited on the death of his father.

By the time Gerrald arrived in the West Indies the plantation was in financial difficulty. Gerrald married but his wife died after giving birth to her second child. Gerrald took his two young children to America where he practised law in Pennsylvania. It was while in America that he met Tom Paine. Gerrald was deeply influenced by Paine's political ideas and when he moved to England in 1788 he became involved in the campaign for parliamentary reform. In 1792 Gerrald joined the London Corresponding Society and the following year wrote the pamphlet A Convention is the Only Means of Saving Us from Ruin.

At an open-air meeting held at Chalk Farm on 24th October, the London Corresponding Society elected Gerrald and Maurice Margarot as its delegates to the Edinburgh Convention planned for November. Before they left London, Margarot and Gerrald heard the news that two of the leaders of the Scottish Reformers, Thomas Fyshe Palmer and Thomas Muir, had been arrested and charged with sedition.

In November 1792, Gerrald and Maurice Margarot arrived in Edinburgh as delegates to the British Convention of the Friends of the People. Government spies also attended these meetings in Edinburgh and on 2nd December 1793, Gerrald, Margarot and William Skirving, secretary of the Society of the Friends of the People, were arrested and charged with sedition.

Joseph Gerrald managed to obtain bail and returned to London. While waiting for his trial to take place, Gerrald heard that Margarot and Skirving had been found guilty of sedition and had been sentenced to 14 years transportation. Gerrald suffered from poor health and his friends were convinced that he would never survive being transported to Australia. Gerrald's friends pleaded with him to flee the country. Gerrald refused, arguing "my honour is pledged; and no opportunity for flight shall induce me to violate that pledge." , William Godwin, wrote a letter to Gerrald praising his decision: "Your trial, if you so please, may be a day such as England, and I believe the world, never saw. It may be the means of converting thousands, and, progressively, millions, to the cause of reason and public justice."

The trial of Joseph Gerrald began on 10th March 1794. He defiantly wore his hair loose and unpowdered in the French style. He made no real attempt to defend himself against the charges and instead concentrated on using the court to express his views on parliamentary reform. Gerrald upset the judge, Lord Braxfield, when he argued that Jesus Christ was a radical reformer. Gerrald ended his speech with the words: "What ever may become of me, my principles will last for ever. Whether I shall be permitted to glide gently down the current of life, in the bosom of my native country, among those kindred spirits whose approbation constitutes the greatest comfort of my living; whether I be doomed to drag out the remainder of my existence amidst thieves and murders, my mind, equal to either fortune, is prepared to meet the destiny that awaits it." Lord Braxfield's response was to sentence Gerrald to fourteen years transportation.

While waiting to be transported to Australia, a government minister, Henry Dundas, offered to arrange for Gerrald to be given his freedom if he promised to stop advocating parliamentary reform. Gerrald refused and on 25th May he left Portsmouth aboard the Sovereign.

Gerrald was seriously ill when he arrived in Australia on 5th November, 1795. John Fyshe Palmer looked after him for several months. Later Palmer claimed that he: "attended him night and day, and the attention of my friends who live with me was equal to mine. Some few hours before his death, he called me to his bedside, 'I die', said he, 'in the best of causes and, as you witness, without repining'." Joseph Gerrald died of tuberculosis on 16th March, 1796.

In 1845 Thomas Hume, the Radical MP, organised the building of a 90 feet high monument in Waterloo Place, Edinburgh. It contained the following inscription: "To the memory of Thomas Muir, Thomas Fyshe Palmer, William Skirving, Maurice Margarot and Joseph Gerrald. Erected by the Friends of Parliamentary Reform in England and Scotland." On the other side of the obelisk, based on the model of Cleopatra's Needle in London, is a quotation from a speech made by Muir on 30th August, 1793: "I have devoted myself to the cause of the people. It is a good cause - it shall ultimately prevail - it shall finally triumph."

Primary Sources

(1) William Godwin, letter to Joseph Gerrald (23rd January 1794)

Your trial, if you so please, may be a day such as England, and I believe the world, never saw. It may be the means of converting thousands, and, progressively, millions, to the cause of reason and public justice. You have a great stake, you place your fortune, your youth, your liberty, and your liberty, and your talents on a single throw. If you must suffer, do not I conjure you, suffer without making use of this opportunity of telling a tale upon which the happiness of nations depends. Spare none of the resources of your powerful mind. What an event would it be for England and mankind if you would gain an acquittal!

(2) Joseph Gerrald, speech during his trial (March, 1794)

After all, the most useful discoveries in philosophy, the most important changes in the moral history of man, have been innovations. The French Revolution was an innovation. Christianity was an innovation...

If, at any early period of my life, it had been announced to me that the task of defending the rights and privileges of nine millions of people would have devolved upon me, a simple individual, I should certainly, from my youth up, have devoted my whole time, that I might be enabled to execute so sacred and important a trust.

What ever may become of me, my principles will last for ever. Whether I shall be permitted to glide gently down the current of life, in the bosom of my native country, among those kindred spirits whose approbation constitutes the greatest comfort of my living; whether I be doomed to drag out the remainder of my existence amidst thieves and murders, my mind, equal to either fortune, is prepared to meet the destiny that awaits it.

(3) Thomas Fyshe Palmer wrote a letter to a friend on the last days of Joseph Gerrald (23rd April, 1796)

Gerrald was at my house the last two months and lay in my rooms. I attended him night and day, and the attention of my friends who live with me was equal to mine. Some few hours before his death, he called me to his bedside, 'I die', said he, 'in the best of causes and, as you witness, without repining'."