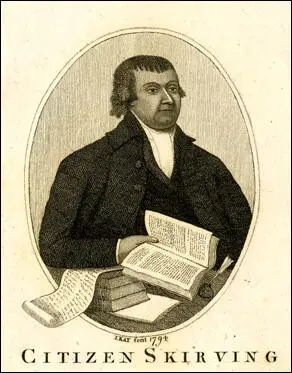

William Skirving

William Skirving, was the son of a prosperous farmer from Midlothian. After being educated at Edinburgh University, he became a tutor to the family of Sir Alexander Dick of Prestonville. This was followed by a period farming at Strathruddie. In 1792 his book on farming, The Husbandman's Assistant, was published.

Skirving married and his wife had eight children. In the 1790s Skirving developed radical political views and in the winter of 1792 became secretary of the recently formed, Scottish Association of the Friends of the People. One of his sons commented: "And it has often struck me, in taking a view of the characters of the leaders of that movement, that on no occasion was there ever such a number of men eminent alike for their moral and religious worth, united for the attainment of a popular right, all of them, with few exceptions, being men who enjoyed the confidence of their fellow citizens, being selected by them to manage their affairs both of a religious and civil description." Between October and December, 1793, Skirving helped to organize a series of meetings in Edinburgh. Government spies also attended these meetings and on 2nd December 1793, Skirving, John Gerrald and Maurice Margarot were arrested at a meeting in Edinburgh.

At his trial Skirving was accused of being a member of the Friends of the People, an organisation formed by Charles Grey and a group of Radical Whigs in London. He was also accused of distributing political pamphlets written and published by Thomas Fyshe Palmer and imitating the "proceedings of the French convention" by calling other members "by the name of citizen".

Skirving was also charged with sedition. To help the jury make their decision, the judge, Lord Braxfield, defined sedition as "violating the peace and order of society". When the jury announced that they found Skirving guilty of the charges, Braxfield pronounced the sentence, "that the said William Skirving, be transported beyond the seas for the space of fourteen years." Skirving commented: "Conscious of innocence, my lords, and that I am not guilty of the crimes laid to my charge, this sentence can only affect me as the sentence of man. It is long since I laid aside the fear of man as my rule. I know that what has been done these two days will be rejudged. That is my comfort, and all my hope."

In February 1793, Skirving and three other men arrested in Scotland and found guilty of writing and publishing pamphlets on parliamentary reform, Thomas Muir, John Fyshe Palmer and Maurice Margarot, were placed on prison Hulks on the Thames in preparation for their journey to Australia.

Radicals in the House of Commons immediately began a campaign to save the men now being described as the Scottish Martyrs. On 24th February, 1793, Richard Sheridan presented a petition to Parliament that described the men's treatment as "illegal, unjust, oppressive and unconstitutional". Charles Fox pointed out in the debate that followed that Palmer had done "no more than what had done by William Pitt and the Duke of Richmond" when they campaigned for parliamentary reform.

Attempts to stop the men being transported failed and on 2nd May 1794, The Surprise left Portsmouth and began its 13,000 mile journey to Botany Bay. While the ship was at sea, a group of convicts, including Skirving and Joseph Fyshe Palmer were accused of being involved in a plot to kill the captain and crew. These charges were dropped when the men arrived in Australia.

As a political prisoner Skirving enjoyed more freedom than other convicts and was allowed to buy a small farm in Sydney. Conditions were very harsh in Australia and on 10th March Joseph Gerrald died of tuberculosis. Nine days later, William Skirving, became the second Scottish Martyr to die when he succumbed to dysentery.

In 1845 Thomas Hume, the Radical MP organised the building of a 90 feet high monument in Waterloo Place, Edinburgh. It contained the following inscription: "To the memory of Thomas Muir, Thomas Fyshe Palmer, William Skirving, Maurice Margarot and Joseph Gerrald. Erected by the Friends of Parliamentary Reform in England and Scotland." On the other side of the obelisk, based on the model of Cleopatra's Needle in London, is a quotation from a speech made by Muir on 30th August, 1793: "I have devoted myself to the cause of the people. It is a good cause - it shall ultimately prevail - it shall finally triumph."

Primary Sources

(1) William Skirving's reaction to being sentenced to be transported to Australia for fourteen years.

Conscious of innocence, my lords, and that I am not guilty of the crimes laid to my charge, this sentence can only affect me as the sentence of man. It is long since I laid aside the fear of man as my rule. I know that what has been done these two days will be rejudged. That is my comfort, and all my hope.

(2) (2) London Morning Post, 17th January, 1794.

Mr Skirving, who was lately sentenced to fourteen years' transportation in Scotland, leaves a wife and eight helpless children behind him.

(3) Governor Hunter of New South Wales, report on the death of William Skirving (March, 1796)

William Skirving, a very decent, quiet, and industrious man, who had purchased a farm, and was indefatigable in his attentions to its improvement, just as the labour of the harvest was near over, was seized with a violent dysentery, of which he died on the 19th of the same month.

(4) One of the sons of William Skirving was asked to make a speech at a meeting held to celebrate the opening of the monument to the Scottish Martyrs (21st August 1844)

In 1793 I was a young man, indeed a boy, but I have a vivid recollection of those who distinguished themselves in the cause of reform. And it has often struck me, in taking a view of the characters of the leaders of that movement, that on no occasion was there ever such a number of men eminent alike for their moral and religious worth, united for the attainment of a popular right, all of them, with few exceptions, being men who enjoyed the confidence of their fellow citizens, being selected by them to manage their affairs both of a religious and civil description.