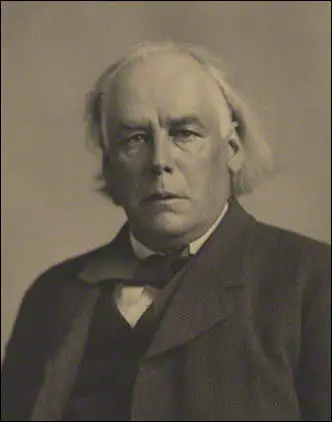

Charles Bradlaugh

Charles Bradlaugh, the eldest of seven children born to Charles Bradlaugh, a solicitor's clerk, and his wife, Elizabeth Trimby Bradlaugh, a former nursemaid, was born in Hoxton, London on 26th September, 1833. He was educated at local elementary day school and became a Sunday School teacher at St Peter's Church. (1)

At the age of twelve he became an office boy in the company where his father worked. As a young man he fell out with his father over religion and was forced to leave home in 1849. He met Elizabeth Sharples, the widow of Richard Carlile, the man who had been sent to prison several times for blasphemy and seditious libel. Although extremely poor Bradlaugh described her as "looking like a queen". (2)

Sharples gave the young boy a home and introduced him to the radical ideas of people like Carlile. She gave him a copy of Carlile's Every Woman's Book, a book "which argued for a rational approach to birth control, attacking the Christian demonization of sexual desire while denying the traditional chauvinist assumptions about women". It was "an important contribution to the nineteenth-century debate on birth control". (3)

Carlile wrote several articles on women's rights. He argued that "equality between the sexes" should be the objective of all reformers. Carlile wrote articles in his newspapers suggesting that women should have the right to vote and be elected to Parliament. Carlile pointed out: "I do not like the doctrine of women keeping at home, and minding the house and the family. It is as much the proper business of the man as the woman; and the woman, who is so confined, is not the proper companion of the public useful man". (4)

In December 1850 Bradlaugh enlisted in the 7th Dragoon Guards and was posted to Ireland. In 1852 his father died, and the following year a legacy from his great-aunt was used to purchase his discharge; he took a job as errand boy (and was soon promoted to clerk) with Thomas Rogers, a solicitor of 70 Fenchurch Street. On 5th June 1855 he married Susannah Lamb Hooper. Their first child, Alice Bradlaugh, was born on 30th April 1856 at their home in Bethnal Green; Hypatia Bonner Bradlaugh followed on 31st March 1858, and Charles Bradlaugh on 14th September 1859. (5)

Charles Bradlaugh - Orator

Bradlaugh was a skilled lawyer, though nominally only a solicitor's clerk; privately, he was also active in politics and was influenced by George Holyoake, a man who was sent to prison for six months for "condemning Christianity" and one of those people converted to atheism. In 1860 joined Joseph Barker, a former Chartist from Sheffield, to establish the radical journal, The National Reformer. Bradlaugh and Barker believed that religion was blocking progress and advocated what they called an atheistic Secularism. The newspaper advocated a whole range of reforms including universal suffrage and republicanism. (6)

Henry Snell was one of those impressed with Bradlaugh's oratory: "Bradlaugh was already speaking when I arrived, and I remember, as clearly as though it were only yesterday, the immediate and compelling impression made upon me by that extraordinary man. I have never been so influenced by a human personality as I was by Charles Bradlaugh. The commanding strength, the massive head, the imposing stature, and the ringing eloquence of the man fascinated me... and I became one of his humblest but most devoted of his followers." (7)

Tom Mann was a young trade unionist when he first heard Bradlaugh speak: "Charles Bradlaugh was at this period, and I think for fully fifteen years, the foremost platform man in Britain. When championing an unpopular cause, it is of advantage to have a powerful physique. Bradlaugh had this; he had also the courage equal to any requirement, a command of language and power of denunciation superior to any other man of his time... He was a thorough-going Republican. Of course, in theological affairs, he was the iconoclast, the breaker of images." (8)

The Reform League

On 23rd February, 1865, Charles Bradlaugh, joined forces with George Odger, Benjamin Lucraft, George Howell, William Allan, Johann Eccarius, William Cremer and several other members of the International Workingmen's Association to establish the Reform League, an organisation to campaign for one man, one vote. Karl Marx told Friedrich Engels "The International Association has managed so to constitute the majority on the committee to set up the new Reform League that the whole leadership is in our hands". (9)

On 2nd July 1866 the Reform League organised "a great street procession and meeting, 30,000 strong, in support of the popular demand for household suffrage... the London press for days after the procession had marched through the principal streets of the fashionable West End, teemed with half-frightened references to its military aspects, good marching, admirable order, well closed column and complete discipline." (10)

William Gladstone, the new leader of the Liberal Party, made it clear that he was in favour of increasing the number of people who could vote. Although the Conservative Party had opposed previous attempts to introduce parliamentary reform, they knew that if the Liberals returned to power, Gladstone was certain to try again. Gladstone was so popular that cheering crowds used to assemble outside his house. (11)

Benjamin Disraeli, leader of the House of Commons, argued that the Conservatives were in danger of being seen as an anti-reform party. In 1867 Disraeli proposed a new Reform Act. Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, (later 3rd Marquess of Salisbury) resigned in protest against this extension of democracy. However, as he explained this had nothing to do with democracy: "We do not live - and I trust it will never be the fate of this country to live - under a democracy." (12)

The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832. (13)

National Secular Society

Charles Bradlaugh formed the National Secular Society, an organisation opposed to Christian dogma. Bradlaugh met Annie Besant and the two of them became close friends. Bradlaugh employed Besant on The National Reformer and over the next few years she wrote many articles on issues such as marriage and women's rights.

In 1877 Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant published The Fruits of Philosophy, written by Charles Knowlton, a book that advocated birth control. Besant and Bradlaugh were charged with publishing material that was "likely to deprave or corrupt those whose minds are open to immoral influences". In court they argued that "we think it more moral to prevent conception of children than, after they are born, to murder them by want of food, air and clothing." Besant and Bradlaugh were both found guilty of publishing an "obscene libel" and sentenced to six months in prison. At the Court of Appeal the sentence was quashed. (14)

Philip Snowden was one of those who saw Bradlaugh make speeches on the subject of birth control. He later recalled: "In those early days I heard a number of famous people. Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant were at the height of their popularity. They had just been prosecuted for the publication of the Knowlton pamphlet on birth control. I heard Bradlaugh speak on the subject, and I can see him now as he stood on the platform. He was a massive figure, with a fine head and a powerful voice, and in declamation he was a tremendous force". (15)

Bradlaugh also took an interest in the subject of inequality in Britain: "The enormous estates of the few landed proprietors must not only be prevented from growing larger, they must be broken up. If they claim that in this we are unfair, our answer is ready. You have monopolized the land, and while you have got each year a wider and firmer grip, you have cast its burdens on others; you have made labour pay the taxes which land could more easily have bourne. You have been intolerant in your power, driving your tenants to the poll like cattle, keeping your labourers ignorant and demoralized." (16)

House of Commons

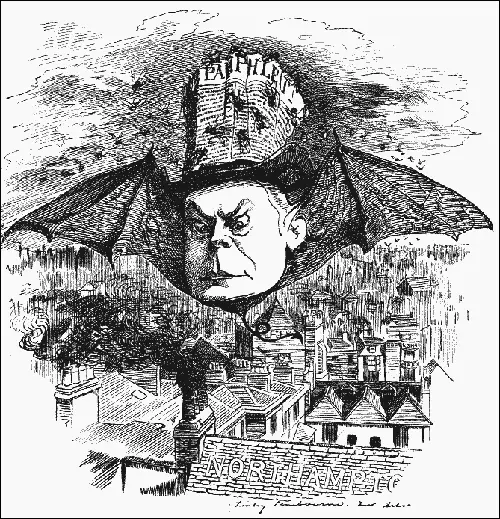

Charles Bradlaugh was a member of the Liberal Party and in the 1880 General Election he won the seat of Northampton. At this time the law required in the courts and oath from all witnesses. Bradlaugh saw this an opportunity to draw attention to the fact that "atheists were held to be incapable of taking a meaningful oath, and were therefore treated as outlaws." (17)

Bradlaugh argued that the 1869 Evidence Amendment Act gave him a right he asked for permission to affirm rather than take the oath of allegiance. The Speaker of the House of Commons refused this request and Bradlaugh was expelled from Parliament. William Gladstone supported Bradlaugh's right to affirm, but as he had upset a lot of people with his views on Christianity, the monarchy and birth control and when the issue was put before Parliament, MPs voted to support the Speaker's decision to expel him. (18)

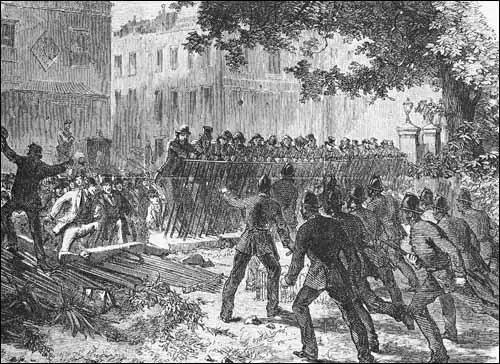

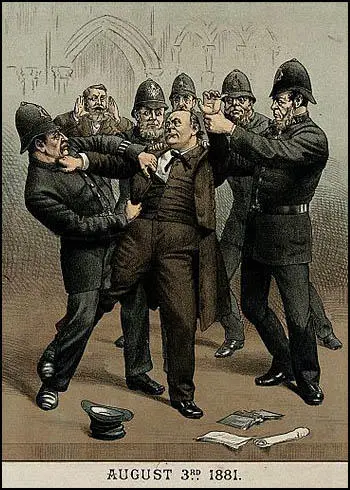

Bradlaugh now mounted a national campaign in favour of atheists being allowed to sit in the House of Commons. Bradlaugh gained some support from some Nonconformists but he was strongly opposed by the Conservative Party and the leaders of the Anglican and Catholic clergy. When Bradlaugh attempted to take his seat in Parliament in June 1880, he was arrested by the Sergeant-at-Arms and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Benjamin Disraeli, leader of the Conservative Party, warned that Bradlaugh would become a martyr and it was decided to release him. (19)

On 26th April, 1881, Charles Bradlaugh was once again refused permission to affirm. William Gladstone promised to bring in legislation to enable Bradlaugh to do this, but this would take time. Bradlaugh was unwilling to wait and when he attempted to take his seat on 2nd August he was once forcibly removed from the House of Commons. Bradlaugh and his supporters organised a national petition and on 7th February, 1882, he presented a list of 241,970 signatures calling for him to be allowed to take his seat. However, when he tried to take the Parliamentary oath, he was once again removed from Parliament. (20)

The authorities attempted to obstruct the activities of Charles Bradlaugh and other freethinkers in the National Secular Society. Pamphlets on religion were seized by the Post Office and on several occasions they were excluded from using public buildings for their meetings. In 1882 the staff of the journal, The Freethinker, were prosecuted for blasphemy, and two of them were found guilty and sent to prison. (21)

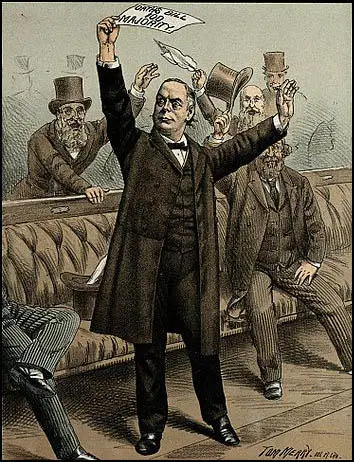

Gladstone's Affirmation Bill was discussed by Parliament in the spring of 1883. The Archbishop of Canterbury and Cardinal Manning, head of the Catholic Church, argued against the right of atheists to be MPs and when the vote was taken in May 1883, the Affirmation Bill was defeated. In 1884 Bradlaugh was once again elected to represent Northampton in the House of Commons. He took his seat and voted three times before he was excluded. He was later fined £1,500 for voting illegally.

Liberalism v Socialism

Annie Besant became a socialist and started working with people such as Walter Crane, Edward Aveling and George Bernard Shaw. This upset Bradlaugh, who regarded socialism as a disruptive foreign doctrine that was based on the idea of violent revolution. This he expressed powerfully in his debate with H. M. Hyndman, the leader of the Social Democratic Federation, in April 1884. Bradlaugh argued that as a member of the Liberal Party he believed the way forward was for the government to pass legislation to protect those suffering from poverty.

"We recognise the most serious evils, and especially in large centres of population; arising out of the poverty already existing, aggravating and intensifying the crime, disease, and misery developed from it.... I want to remedy the evil, attacking it in detail by the action of the individuals most affected by it... Social reform is one thing because it is reform; Socialism is the opposite because it is revolution... Now I have said that in order to effect Socialism in this country – and I am only dealing with this country – it would require a physical-force revolution, because you would want that physical force to make all the present property-owners who are unwilling, surrender their private property to the common fund – you would want that physical force to dispossess them." (22)

Charles Bradlaugh was elected once again for Northampton in the 1885 General Election. He tried again to take the oath on 13th January, 1886. The new Speaker, Sir Arthur Wellesley Peel, did not object, arguing that he had to authority to interfere with the oath-taking. Bradlaugh now had the right to speak and vote in the House of Commons. Bradlaugh now became a loyal supporter of William Gladstone, the prime minister, who had a radical agenda. (23)

On 8th April 1886, William Gladstone announced his plan for Irish Home Rule which proposed a separate parliament for Ireland in Dublin and that there would be no Irish MPs in the House of Commons. The Irish Parliament would manage affairs inside Ireland, such as education, transport and agriculture. However, it would not be allowed to have a separate army or navy, nor would it be able to make separate treaties or trade agreements with foreign countries. (24)

The Conservative Party opposed the measure. So did some members of the Liberal Party, led by Joseph Chamberlain, also disagreed with Gladstone's plan. Chamberlain main objection to Gladstone's Home Rule Bill was that as there would be no Irish MPs at Westminster, Britain and Ireland would drift apart. He added that this would be amounting to the start of the break-up of the British Empire. When a vote was taken, there were 313 MPs in favour, but 343 against. Although Bradlaugh supported Gladstone, 93 Liberals voted against the measure. (25)

Bradlaugh also attacked the idea of the British Empire. This position was criticised by Tory leader, Benjamin Disraeli: "Gentlemen, there is another and second great object of the Tory party. If the first is to maintain the institutions of the country, the second is, in my opinion, to uphold the empire of England. If you look to the history of this country since the advent of Liberalism - forty years ago - you will find that there has been no effort so continuous, so subtle, supported by so much energy, and carried on with so much ability and acumen, as the attempts of Liberalism to effect the disintegration of the empire of England." (26)

Charles Bradlaugh suffered for many years with cardiac asthma and hereditary kidney weakness. He died on 30th January, 1891. His funeral was attended by 3,000 mourners who saw him buried in unconsecrated ground.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1877 Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh attempted to publish The Fruits of Philosophy in Britain. The couple were immediately arrested and charged with publishing an 'obscene' book. Hardinge Gifford, the public prosecutor, explained why Besant and Bradlaugh were on trial.

I say that this is a dirty, filthy book, and the test of it is that no human being would allow that book on his table, no decently educated English husband would allow even his wife to have it…the object of it is to enable a person to have sexual intercourse, and not to have that which in the order of providence is the natural result of that sexual intercourse. That is the only purpose of the book and all the instruction in the other parts of the book leads up to that proposition.

(2) Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh were both found guilty and sentenced to six months imprisonment, and fined £200. However in February 1878, the Court of Appeal reversed the judgement and the sentence was quashed. Annie Besant responded to this decision by writing her own book on birth control. She explained in her autobiography her reasons for this.

I wrote a pamphlet entitled The Law of Population giving the arguments which had convinced me of its truth, the terrible distress and degradation entailed on families by overcrowding and the lack of necessaries of life, pleading for early marriages that prostitution might be destroyed, and limitation of the family that pauperism might be avoided, finally giving the information which rendered early marriage without these evils possible. This pamphlet was put in circulation as representing our views on the subject.

We continued the sale of Knowlton's Fruits of Philosophy for some time until we received an intimation that no further prosecution would be attempted, and on this we at once dropped its publication, substituting for it my Law of Population.

(3) Charles Bradlaugh, The Impeachment of the House of Brunswick (1880)

Her Majesty is now enormously rich, and - as she is like her Royal grandmother - grows richer daily. She is also generous, and has recently given not quite half a day's income to the starving poor of India.

(4) Charles Bradlaugh, The Land, the People, and the Coming Struggle (1877)

The enormous estates of the few landed proprietors must not only be prevented from growing larger, they must be broken up. If they claim that in this we are unfair, our answer is ready. You have monopolized the land, and while you have got each year a wider and firmer grip, you have cast its burdens on others; you have made labour pay the taxes which land could more easily have bourne. You have been intolerant in your power, driving your tenants to the poll like cattle, keeping your labourers ignorant and demoralized.

(5) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934) page 43

In those early days I heard a number of famous people. Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant were at the height of their popularity. They had just been prosecuted for the publication of the Knowlton pamphlet on birth control. I heard Bradlaugh speak on the subject, and I can see him now as he stood on the platform. He was a massive figure, with a fine head and a powerful voice, and in declamation he was a tremendous force.

(6) Henry Snell, Men Movements and Myself (1936) page 30

The controversy which had arisen over the question of Charles Bradlaugh's claim to be admitted to Parliament had made his name a household word throughout the country, and when it was announced that he would shortly visit Nottingham I determined that I would try and see him and hear him speak. The subject of his lecture was Ireland. Bradlaugh was already speaking when I arrived, and I remember, as clearly as though it were only yesterday, the immediate and compelling impression made upon me by that extraordinary man. I have never been so influenced by a human personality as I was by Charles Bradlaugh. The commanding strength, the massive head, the imposing stature, and the ringing eloquence of the man fascinated me, and from that hour until the day of his death, ten years later, I was one of his humblest but most devoted of his followers.

Taking him all in all - as man, orator, as leader of unpopular causes, and as an incorruptible public figure, he was the most imposing human being that I have ever known, and I do not expect to look upon his like again. I have seen strong men, under the storm of his passion, rise from their seats, and sometimes weep with emotion. Like a prodigal he threw away with both hands the energies of a precious life, and he died, exhausted, by the early age of fifty-seven.

(7) Charles Bradlaugh, speech at St James’ Hall (17th April, 1884)

Friends, the distinction between myself and my antagonist is this. We both recognise - I am not quite sure from his speech how far we actually clearly recognise – we both recognise many social evils. He wants the State to remedy them, I want the individuals to remedy them. I will tell you, and I want the evil of interruption remedied by your individually holding your tongue. We recognise the most serious evils, and especially in large centres of population; arising out of the poverty already existing, aggravating and intensifying the crime, disease, and misery developed from it. My antagonist wants to cure that by some indefinite organisation. It may be definite to you. It is not to me yet - and I will show you so when I follow what he has said. I want to remedy the evil, attacking it in detail by the action of the individuals most affected by it. I do not wonder that men call themselves Socialists. The evils are grave enough to make men willing to take any name that they may connect with a possible cure. What I shall try to do is to show that the cure does not lie in the direction pointed out in the speech we have listened to, and I have to complain that we have had no definition of Socialism, that the two very vague phrases which commenced the speech were as far from being a definition as any phrases can possibly be. Unless we can understand one another there is no use in discussing with one another. I shall try at least to make the position I take clear, and I will begin by distinguishing between social reformers and Socialists. Getting the vote for women may be done without being a member of the Democratic Federation, and there are no political or social evils which have been referred to in the speech of tonight, nor any one of the remedies for them, that were not discussed so long ago that they may be found in the old Chartist Circular of 1840. I do not mean that they are less worth discussing now, but I do mean that they have not the newness that has been claimed for them in the speech to which we have just listened. Social reform is one thing because it is reform; Socialism is the opposite because it is revolution – and that I am sorry to see is approved by my antagonist. Revolution, as he says, to be effected by argument if possible. Aye, but by what if argument be not possible? Force. Yes, that is the curse, and that is why I deem it my duty to be here at the expense of much misrepresentation, for the purpose of diverting and turning away this argument of force which holds weapons to our enemies, and which hurts and damns our cause. Let me here point out that which has been already stated roughly in the speech to which have listened, namely, that no Socialistic experiment has ever yet succeeded in the world. None ever! Some have seemed to be temporarily successful, but only so long as they have been held together, either by some religious tie, and then they have broken up when the effect of the tie has failed, and of this there are numerous illustrations; or by personal devotion to some one man, and then they have broken up when that man has grown weary, or when his life has ceased; or when directed by some strong chief or chiefs, holding together only so long as the direction lasted. Then they have only been temporarily successful, while they have been very few in number. When their apparent success has tempted many to join them, then they have broken down, and I will tell you why. As long as they were few, they did not lose the sense of private property; they did not lose sight of the advantage they were gaining by their individual exertions. The small community owned its property hostile to, or at least distinct from, that of every property around it, and therefore each one knew every addition he had made to the common stock; the stock was so small that he could count his increased richness. I have complained that we have heard no definition of Socialism, and the complaint would be unfair indeed unless I were prepared to give what I believe to be a definition. I will do it at once. I say that Socialism denies individual private property. I will show you that it does in the last words which fell from the speaker when he had forgotten to speak cautiously, and it is not unnatural – I shall probably do the same – it is not unnatural that the enthusiasm of such a meeting as this should induce one not to speak cautiously. I am glad he did not, because he spoke accurately then from his own position. I say that Socialism denies all individual private property, and affirms that society organised as the State... this gentleman (Mr. Hyndman) is the representative for the moment and affirms that society organised as the State should own all wealth, direct all labour, and compel the equal distribution of all produce. I say that is what the vague, words amount to. What does the collective ownership of all the means of wealth, and of the results of labour mean, if it does not mean that? What does the organised direction of work through the State mean, if it does not mean that? If the words are only counters to jingle in the ears of the hungry, then they are not only no good, but may result in serious mischief. I say that a Socialistic state, would be that state of society in which everything would be held in common, in which the labour of every individual would be directed and controlled by the State, to which State would belong all results of labour. I urge the importance of exact definitions.

The gentleman says that he represents a body which has issued some programme. One of the persons signing that programme writes himself, and he actually complains that the opponents of Socialism want too much definition and too much explanation of what is to be done, and he says that scientific Socialism gives no details. Dare you try to organise society without discussing details? It is the details of life which make up life. The men who neglect details are lost in a fog, they have no sure path. You might as well build a house without bricks as discuss a scheme without details, and I object to vague phrases which may mean anything or nothing, and I object to being told that this is to be done by a revolution, to be effected by argument if possible.... And I object that if a Socialistic State could be realised it could only be done by revolution; that it would require in effect two revolutions, one a revolution of physical force and the other a mental revolution, and I will show you that both of them are impossible. Permit me to say, even if you are wiser than myself, you had better hear me first – to laugh at me before hearing me may be Socialistic, but it is not common sense. I object, if the two revolutions could be effected, and if Socialism could be realised, that then it would be fatal to all progress by neutralising and paralysing individual effort, and I say that civilisation has only been in proportion to the energy and enterprise of the individual. Now I have said that in order to effect Socialism in this country – and I am only dealing with this country – it would require a physical-force revolution, because you would want that physical force to make all the present property-owners who are unwilling, surrender their private property to the common fund – you would want that physical force to dispossess them.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)