Irish Home Rule

In 1823 Daniel O'Connell, Richard Lalor Sheil and Thomas Wyse formed the Catholic Association. As Vincent Comerford has pointed out: "At O'Connell's insistence the new body had a stated objective much wider than the simple ‘relief’ or emancipation which would allow a small minority of Catholics like himself to proceed to inner bar, bench, or parliament: it was to address all the concerns of the Roman Catholic collectivity. This signalled the start of a mobilization of the populace for constitutional political ends which had little precedent anywhere, was contrary to the instincts of contemporary Liberals, and was to make O'Connell a historical figure of European significance." (1)

In its first manifesto the Catholic Association argued: "The catholics of Ireland have long been engaged in a painful and anxious struggle to attain, by peaceful and constitutional means, those civil rights, to which every subject of these realms is entitled, and of which our forefathers were basely... deprived ... At no former period of this protracted struggle had the catholic people of Ireland so little reason to entertain hope of immediate success... but they do not dare to despair. They know that their cause is just and holy. It is the cause of religion and liberty. It is the cause of their country and their God." (2)

O'Connell turned the Catholic Association into a mass organisation by inviting the poor to become associate members for a shilling a year. Catholic priests were encouraged to advertise the Catholic Association and were employed as recruiting agents. "The Association had a ready network of agents in every parish to stir opinion and to collect the penny a month Catholic Rent to finance the agitation." (3)

Catholic Emancipation

The Catholic Association campaigned for the repeal of the Act of Union, the end of the Irish tithe system, universal suffrage and a secret ballot for parliamentary elections. Although O'Connell rejected the use of violence he constantly warned the British government that if reform did not take place, the Irish masses would start listening to the "counsels of violent men". (4)

By 1826 the Catholic Association began supporting candidates in parliamentary elections. They had some spectacular victories, including Daniel O'Connell defeating C. E. Vesty Fitzgerald, President of the Board of Trade, in a County Clare by-election. However, as a Catholic, O'Connell could not take the Oath of Supremacy, which was incompatible with Catholicism and so could not take his seat in the House of Commons. (5)

Radical MPs such as Sir Francis Burdett and Joseph Hume, had been arguing for some years that Parliament should bring an end to anti-Catholic legislation. After O'Connell's victory, even Tories such as Sir Robert Peel and Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, began arguing for reform. They warned their Conservative colleagues that here would be civil war in Ireland unless the law was changed. The Roman Catholic Relief Bill was published in March 1829. O'Connell wrote to his wife: "Peel's bill for Emancipation, is good - very good, frank, direct, complete; no veto, no control". (6)

In 1829 the British Parliament passed the Roman Catholic Relief Act, which granted Catholic Emancipation. O'Connell was less pleased with the Irish Parliamentary Election Bill, that raised the threshold for the county franchise from 40s. to £10, thereby disenfranchising the bulk of his electoral support. As a result of this legislation the Irish electorate was reduced from 200,000 to 26,000. (7)

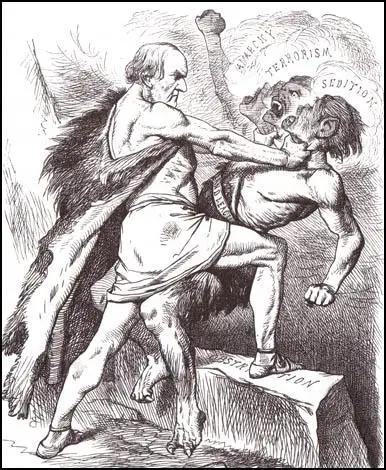

Daniel O'Connell celebrating Catholic Emancipation (1829)

The government also outlawed the Catholic Association. However, on 30th May, 1829, O'Connell was returned unopposed for County Clare and he took his seat on 4th February 1830. Over the next few years O'Connell became a major figure in the House of Commons. He was active in the campaigns for prison and law reform, free trade, the abolition of slavery and Jewish emancipation. He was also a prominent figure in the campaign for universal suffrage. After the disappointment of the 1832 Reform Act, British Radicals adopted the tactics that had been used by O'Connell successfully in Ireland. Organizations such as the Chartists used O'Connell's methods of organizing and applying the pressure of public opinion while implying that if this was not successful, the movement might resort to violence. (8)

O'Connell had a major influence on MPs. Of the105 Irish MPs, 45 loyally supported O'Connell, including Feargus O'Connor, who was later to become one of the main leaders of the Chartist movement. O'Connell's control over this group enabled him to exert considerable pressure on the government. In 1835 O'Connell and fellow Catholic MPs agreed to support Lord Melbourne and his Whig government in return for significant Irish reforms. Although the Whig government passed the Tithe Commutation Bill and the Irish Municipal Reform Act, O'Connell thought this was inadequate. He was also totally opposed to the passing of the Irish Poor Law and when the Whigs refused to change it, O'Connell withdrew his group's support for the government. (9)

The Corn Laws and the Rise of Irish Nationalism

Sir Robert Peel attempted to overcome the religious conflict in Ireland by setting up the Devon Commission to inquire into the "state of the law and practice in respect to the occupation of land in Ireland." However, Peel's attempts to improve the situation in Ireland was severely damaged by the 1845 potato blight. The Irish crop failed, therefore depriving the people of their staple food. Peel was informed that three million poor people in Ireland who had previously lived on potatoes would require cheap imported corn. Peel realised that they only way to avert starvation was to remove the duties on imported corn. (10)

The first months of 1846 were dominated by a battle in Parliament between the free traders and the protectionists over the repeal of the Corn Laws. William Gladstone gave Peel his loyal support. Benjamin Disraeli became the leader of the group that opposed Peel. He was accused of using this difficult situation to undermine the Prime Minister. However, he later told a fellow MP that he did this "because, from my earliest years, my sympathies had been with the landed interest of England". (11) Disraeli made a stinging attack on Peel when he accusing him of betraying "the independence of party" and thus "the integrity of public men, and the power and influence of Parliament itself". (12)

An alliance of free-trade Conservatives (Peelites), Radicals, and Whigs assured the repeal of the Corn Laws. However, it caused a split in the Conservative Party. "It was not a straight division of landed gentry against the rest. It was a division between those who considered that the retention of the corn laws was an essential bulwark of the order of society in which they believed and those who considered that the Irish famine and the Anti-Corn Law League had made retention even more dangerous to that order than abandonment." (13)

The Irish famine increased support for radical figures in the country. This included John Mitchel, who formed a new newspaper, The United Irishmen and issued a manifesto that stated: "Our independence must be had at all hazards. If the men of property will not support us, they must fall; we can support ourselves by the aid of that numerous and respectable class of the community, the men of no property.. To enforce and apply these principles - to make Irishmen thoroughly understand them, lay them up to their hearts, and practise them in their lives - will be the sole and constant study of the United Irishman". (14)

Mitchel urged a change of policy: "Give us war in our time, O'Lord... the legal and constant agitation in Ireland, is a delusion... every man ought to have arms and to promote their use of them" and he called for a war of vengeance against England in order to achieve "an Irish Republic, one and indivisible". Michel also wanted to remove absentee landlords on the grounds that the land belonged to the Irish people. He wanted "a nation of independent peasant proprietors". (15)

Edward Stanley, the future 15th Earl of Derby, argued in the House of Lords that Mitchel was encouraging "sedition and rebellion among her Majesty's subjects in Ireland". He added that he would not have been so worried if Mitchel's articles had been published in England: "But this language is addressed, not to the sober-minded and calm-thinking people of England, but to a people, hasty, excitable, enthusiastic and easily stimulated, smarting under great manifold distresses, and who have been for years excited to the utmost pitch to which they could go consistently with their own safety, by the harangues of democrats and revolutionists". (16)

On 13th May 1848, Mitchel was served a warrant for his arrest under the recently passed Treason Felony Act. The warrant stated that "John Mitchel... did wilfully and feloniously compass, imagine, invent, devise, and intend to deprive and depose our most Gracious Lady the Queen, from the style, honour, and royal name of the imperial crown of the United Kingdom, and levy war against her Majesty, in order, by force and constraint, to compel her to change her measures and counsels; and such compassings, imaginations, inventions, devices, and intentions, did... express, utter and declare, by publishing certain printings in a certain news paper called The United Irishman." (17)

Mitchel was convicted of treason and sentenced to be transported to Australia for 14 years. Mitchel stated in court: "The law has now done its part, and the Queen of England, her crown and Government in Ireland, are now secure pursuant to Act of Parliament. I have done my part also.... My lord, I knew I was setting my life on that cast; but I warned him that in either event the victory would be with me, and the victory is with me. Neither the jury, nor the judges, nor any other man in this court, presumes to imagine that it is a criminal who stands in this dock.... I have shown that her Majesty's Government sustains itself in Ireland by packed juries by partisan judges, by perjured sheriffs. I have acted all through this business, from the first, under a strong sense of duty. I do not repent anything I have done." (18)

Mitchel then went on to say: "I believe that the course which I have opened is only commenced, The Roman who saw his hand burning to ashes before the tyrant, promised that three hundred should follow out his enterprise, Can I not promise for one, for two, for three, aye, for hundreds". His speech did trigger a rebellion in Ireland in July, 1848, led by William Smith O'Brien. It was all over in a few weeks. Paul Adelman has commented: "It was a hopeless affair from the start. It was badly led and badly organised; there was no mass support from a half-starved and demoralised." (19)

Church Tithes

In December, 1867, Lord John Russell resigned and William Ewart Gladstone became the leader of the Liberal Party. He immediately announced that he intended to tackle the problem of Church Tithes. The law at that time stated that all landowners and farmers had to pay money to the Church of England every year. The amount depended on the amount of land you had. These payments were called tithes. English farmers complained about this tax but as most of them were Protestants they accepted it. In Ireland most people were Roman Catholics, "so they were having to pay money to a church which they did not belong to, and going to a church which they did not belong to... so what was fair in England was most unfair in Ireland." (20)

In February, 1868, Gladstone moved and carried a bill to abolish compulsory church rates, an issue which united radicals, libertarians, nonconformists and those Anglicans unwilling to defend the status-quo. Gladstone followed this by carrying with a majority of sixty-five votes the first of three resolutions to abolish the Anglican establishment in Ireland. By taking this action Gladstone was able to heal the divisions in the Liberal Party, that had been divided over the issue of parliamentary reform. However, the House of Lords blocked the measure. (21)

Gladstone later argued that the decision publicly to advocate Irish disestablishment was an example of "a striking gift" endowed on him by Providence, which enabled him to identify a question whose moment for public discussion and action had come. Henry Labouchere, a fellow Liberal MP, responded by saying that he "did not object to the old man always having a card up his sleeve, but he did object to his insinuating that the Almighty had placed it there." (22)

In the 1868 General Election, Gladstone made Church tithes a major issue in the campaign. The Liberals won 387 seats against the 271 of the Conservatives. Robert Blake believes the Irish issue was an important factor in Gladstone's victory. "Gladstone could not have selected a better issue on which to unify his own party and divide his opponents". The Liberals did especially well in the cities because of the "existence of a large Irish immigrant population". (23)

Gladstone told the House of Commons that he intended to make changes in the law which said that all Irishmen had to pay tithes to the Established Church. As he pointed out, as around 90% of the population were Catholics, it was unfair that this money went to the Protestant Church. He announced that in future the Protestant Church of Ireland would have to pay for itself out of what its members gave it. Protestants held protest meetings and Gladstone was described as "a traitor to his Queen, his country and his God". (24)

The Conservatives in the House of Lords resisted the Irish Church Bill, forcing a compromise on the financial terms but without rejecting it in principle. This was followed by an Irish Land Bill in 1870. "The fact of the passing of the bill was important, but its complexity bewildered as much as appealed; it alarmed the propertied classes but did not gain the sort of enthusiastic Irish response of the church bill a year earlier". (25)

Irish Land Act

The 1880 General Election was a great victory for the Liberal Party who won 352 seats with 54.7% of the vote. Benjamin Disraeli resigned and William Ewart Gladstone became prime minister. Gladstone's first Irish Land Act had been a failure. He was now coming under pressure from the Irish Land League that had been taking the law into their own hands and in the last three months of 1880, 1,696 crimes against Irish landlords took place. In February 1881 Gladstone asked Parliament to pass a Coercion Act, which meant that people suspected of crimes could be arrested and kept in jail without trial. (26)

In April 1881 Gladstone introduced his Second Land Bill in the House of Commons. It included three of the demands advocated by the Land League: (a) Fair Rents: To be decided by a court if the landlord and the tenant could not agree on what was fair. (b) Fixture of Tenure: The Tenant could stay in his farm as long as he wished, provided he paid the rent. (c) Free Sale: If a tenant left his farm he would be paid for any improvements he had made to it. Despite opposition from the House of Lords the bill became law in August 1881. (27)

Historians have been highly critical of this measure. Paul Adelman, the author of Great Britain and the Irish Question (1996) has pointed out: "Despite his masterly performance in pushing the complicated Land bill through the Commons in the summer of 1881, recent historians have argued that Gladstone again failed to face up to the economic realities of rural Ireland. For in the west of Ireland particularly, it was the lack of cultivable land rather than the problem of rents that was the fundamental problem for the smallholders." (28)

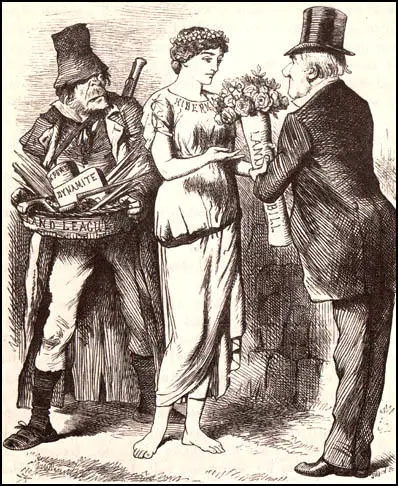

Charles Stewart Parnell, the leader of the Irish Land League, criticised several aspects of the Act (such as the exclusion of tenants in arrears from its provisions). In a speech in October 1881, Gladstone warned Parnell of taking direct action. "If there is to be fought a final conflict in Ireland between law on the one side and sheer lawlessness on the other... then I say... the resources of civilisation are not exhausted." (29) Parnell responded by denouncing the Liberal leader as "a masquerading knight errant, the pretending champion of the rights of every other nation except those of the Irish nation". (30)

Irish Home Rule

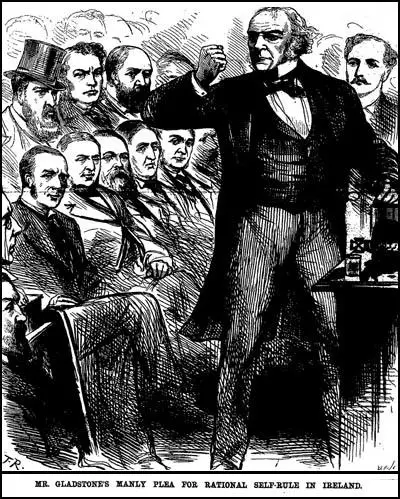

Gladstone and the Liberals won the 1885 General Election, with a majority of seventy-two over the Tories. However, the Irish Nationalists could cause problems because they won 86 seats. On 8th April 1886, Gladstone announced his plan for Irish Home Rule. Mary Gladstone Drew wrote: "The air tingled with excitement and emotion, and when he began his speech we wondered to see that it was really the same familiar face - familiar voice. For 3 hours and a half he spoke - the most quiet earnest pleading, explaining, analysing, showing a mastery of detail and a grip and grasp such as has never been surpassed. Not a sound was heard, not a cough even, only cheers breaking out here and there - a tremendous feat at his age... I think really the scheme goes further than people thought." (31)

The Home Rule Bill said that there should be a separate parliament for Ireland in Dublin and that there would be no Irish MPs in the House of Commons. The Irish Parliament would manage affairs inside Ireland, such as education, transport and agriculture. However, it would not be allowed to have a separate army or navy, nor would it be able to make separate treaties or trade agreements with foreign countries. (32)

The Conservative Party opposed the measure. So did some members of the Liberal Party, led by Joseph Chamberlain, also disagreed with Gladstone's plan. Chamberlain main objection to Gladstone's Home Rule Bill was that as there would be no Irish MPs at Westminster, Britain and Ireland would drift apart. He added that this would be amounting to the start of the break-up of the British Empire. When a vote was taken, there were 313 MPs in favour, but 343 against. Of those voting against, 93 were Liberals. They became known as Liberal Unionists. (33)

Gladstone responded to the vote by dissolving parliament rather than resign. During the 1886 General Election he had great difficultly leading a divided party. According to Colin Matthew: "So dedicated was Gladstone to the campaign that he agreed to break the habit of the previous forty years and cease his attempts to convert prostitutes, for fear, for the first time, of causing a scandal (Liberal agents had heard that the Unionists were monitoring Gladstone's nocturnal movements in London with a view to a press exposé)". (34)

In the election the number of Liberal MPs fell from 333 in 1885 to 196, though no party gained an overall majority. Gladstone resigned on 30th July. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, once again became prime minister. Queen Victoria wrote him a letter where she said she always thought that his Irish policy was bound to fail and "that a period of silence from him on this issue would now be most welcome, as well as his clear patriotic duty." (35)

William Gladstone refused to retire and continued as leader of the opposition. He wrote several articles on the subject of Home Rule and questioned the idea that the House of Lords should be able to block government legislation. Although he remained active in politics, a decline in his hearing and eyesight made life difficult. "His memory, particularly for names but also for recent events, although not for more distant ones, showed signs of fading... On the other hand his physical stamina remained formidable. He felled his last tree a few weeks before his eighty-second birthday." (36)

In the 1892 General Election held in July, Gladstone's Liberal Party won the most seats (272) but he did not have an overall majority and the opposition was divided into three groups: Conservatives (268), Irish Nationalists (85) and Liberal Unionists (77). Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, refused to resign on hearing the election results and waited to be defeated in a vote of no confidence on 11th August. Gladstone, now 84 years old, formed a minority government dependent on Irish Nationalist support. (37)

A Second Home Rule Bill was introduced on 13th February 1893. Gladstone personally took the bill through the "committee stage in a remarkable feat of physical and mental endurance". (38) After eighty-two days of debate it was passed in the House of Commons on 1st September by 43 votes (347 to 304). Gladstone wrote in his diary, "This is a great step. Thanks be to God." (39)

On 8th September, 1893, after four short days of debate, the House of Lords rejected the bill, by a vote of 419 to 41. "It was a division without precedent, both for the size of the majority and the strength of the vote. There were only 560 entitled to vote, and 82 per cent of them did did so, even though there was no incentive of uncertainty to bring remote peers to London." (40)

It is s alleged that Gladstone considered resigning and calling a new general election on the issue. However, he suspected that he could not mount a successful electoral indictment of the House of Lords on Irish Home Rule. He therefore pushed ahead with the Workmen's Compensation Act, a measure that was extremely unpopular with employers. The act dealt with the right of workers for compensation for personal injury. It replaced the Employer's Liability Act 1880, which required the injured worker the right to sue the employer and put the burden of proof on the employee. Gladstone thought that when the Lords blocked the bill he could call an election and win.

However, in December 1893, Gladstone came into conflict with his own party over the issue of defence spending. The Conservative Party began arguing for an expansion of the Royal Navy. Gladstone made it clear that he was opposed to this policy. William Harcourt, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was willing to increase naval expenditure by £3 million. John Poyntz Spencer, the First Lord of the Admiralty, agreed with Harcourt. Gladstone refused to budge on the issue and wrote that he would not "break to pieces the continuous action of my political life, nor trample on the tradition received from every colleague who has ever been my teacher" by supporting naval rearmament. (41)

Conservatives continued to block the government's legislation. After accepting the Lords' amendments to the Local Government Bill "under protest" he decided to resign. In his last speech to the House of Commons on 1st March, 1894, he suggested that the time had come to change the rules of the British Parliament so that the House of Lords would no longer have the power to refuse to pass Bills which had been passed by the House of Commons. (42)

Primary Sources

(1) The Committee of the Catholic Association (1824)

The catholics of Ireland have long been engaged in a painful and anxious struggle to attain, by peaceful and constitutional means, those civil rights, to which every subject of these realms is entitled, and of which our forefathers were basely... deprived ... At no former period of this protracted struggle had the catholic people of Ireland so little reason to entertain hope of immediate success... but they do not dare to despair. They know that their cause is just and holy. It is the cause of religion and liberty. It is the cause of their country and their God... But, in order effectively to exert the energies of the Irish people, pecuniary resources are absolutely necessary... Your committee propose: that a monthly subscription should be raised throughout Ireland, to be denominated "The monthly catholic rent" ... care to be taken to publish in or near each catholic chapel as may be permitted by the clergy, the particulars of the sums subscribed ... and that the amount expected from each individual shall not exceed one penny per month.

(2) Lord Edward Stanley, speech in the House of Lords (24th February, 1848)

The purpose of exciting sedition and rebellion among her Majesty's subjects in Ireland… it is language used in no common way, and for this reason I have called the attention of her Majesty's Government to it. This is not a mere casual article in a newspaper - it is the declaration of the aim and object for which it is established, and of the design with which its promoters have set out; that object being to do everything possible to drive the people of Ireland to sedition, to urge them into open rebellion, and to promote civil war for the purpose of exterminating every Englishman in Ireland. I hope, my Lords, her Majesty's Government will not say that this is a matter quite in theory - that it is below contempt, and that we should allow it to pass by in silence. If such a publication had appeared in England, I should have been very much inclined to think the good sense and sound judgment of the people would have rejected the article at once as a seditious invective, whose very violence, like an overdose of poison, prevented its effect.

But this language is addressed, not to the sober-minded and calm-thinking people of England, but to a people, hasty, excitable, enthusiastic and easily stimulated, smarting under great manifold distresses, and who have been for years excited to the utmost pitch to which they could go consistently with their own safety, by the harangues of democrats and revolutionists.

This paper was published at five pence, but, as I am informed, when the first number appeared, so much was it sought after, that, on its first appearance, it was eagerly bought in the streets of Dublin at one shilling and sixpence and two shillings a number. With the people of Ireland, my lords, this language will tell; and I say it is not safe for you to disregard it. These men are honest; they are not the kind of men who make their patriotism the means of barter for place or pension. They are not to be bought off by the Government of the day for a colonial place, or by a snug situation in the customs or excise. No; they honestly repudiate this course; they are rebels at heart, and they are rebels avowed, who are in earnest in what they say and propose to do.

My Lords, this is not a fit subject, at all events, for contempt. My belief is, that these men are dangerous - my belief is, that they are traitors in intent already, and if occasion offers, they will be traitors in fact. You may prosecute them—you may convict them; but depend upon it, my Lords, it is neither just to them, nor safe for yourselves, to allow such language to be indulged in. I believe, because I have this strong persuasion of the earnestness and honesty of these men, that it is my duty to call your Lordships' attention to the first number of this paper, called The United Irishman, which is intended to produce an excitement leading to rebellion, for the purpose of showing you the language held forth, and the object avowed by these men, to whom a large portion of the people of Ireland look up with confidence, and for the purpose of asking her Majesty's Government if this paper has come under their consideration, and if so, whether the Law Officers in Ireland have been consulted, and if it is the intention of the Government to take any notice of it.

(3) John Mitchel, speech in court (27th May 1848)

The law has now done its part, and the Queen of England, her crown and Government in Ireland, are now secure pursuant to Act of Parliament. I have done my part also. Three months ago I promised Lord Clarendon, and his government, in this country, that I would provoke him into his courts of justice, as places of this kind are called, and that I would force him publicly and notoriously to pack a Jury against me to convict me, or else that if I would walk out a free man from this dock, to meet him in another field. My lord, I knew I was setting my life on that cast; but I warned him that in either event the victory would be with me, and the victory is with me. Neither the jury, nor the judges, nor any other man in this court, presumes to imagine that it is a criminal who stands in this dock.

I have kept my word. I have shown what the law is made of in Ireland. I have shown that her Majesty's Government sustains itself in Ireland by packed juries by partisan judges, by perjured sheriffs. I have acted all through this business, from the first, under a strong sense of duty. I do not repent anything I have done: and I believe that the course which I have opened is only commenced, The Roman who saw his hand burning to ashes before the tyrant, promised that three hundred should follow out his enterprise, Can I not promise for one, for two, for three, aye, for hundreds.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)