Benjamin Lucraft

Benjamin Lucraft, the second son of the eleven children, was born in Exeter on 28th November 1809.

He worked as a ploughboy as a youth, and was indentured as an apprentice in husbandry, but also gained experience in cabinet-making and established a workshop in Taunton. (1)

In 1830 he married Mary Pearce and within a year his first son was born. He established a cabinet-making business in Shoreditch. Over the next few years his wife gave birth to four more children. (2)

Lucraft joined the Temperance Society in 1846. At first temperance usually involved a promise not to drink spirits and members continued to consume wine and beer. However, by the late 1840s temperance societies began advocating teetotalism. This was a much stronger position as it not only included a pledge to abstain from all alcohol for life but also a promise not to provide it to others.

Benjamin Lucraft and Manhood Suffrage

Benjamin Lucraft became a supporter of Chartism and attended the Kennington Common demonstration on 10th April 1848. He chaired the annual Chartist conference in February 1858 when Ernest Jones was elected sole executive and laid out a political programme that looked away from inflexible six-point Chartism and moved towards co-operation with other supporters of parliamentary reform. (3)

George Howell claims that "He (Lucraft) was never a very effective speaker, but he was able always to put his points forcibly, because he knew what he wanted and could see tolerably clearly the way in which it could be obtained. In his earlier days he was thought to be an implacable Chartist, and nothing else; but he was not the man to oppose reform because all that he desired was not granted. Lucraft was sternly devoted to 'principles', but he acknowledged the value of compromise when it was a question of something or nothing. He was unswerving in his advocacy of chartism and teetotalism." (4)

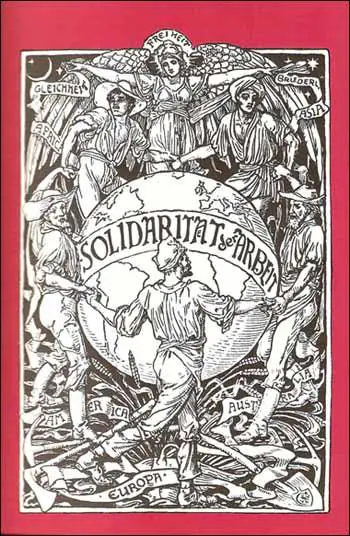

Lucraft promoted the cause of parliamentary suffrage through the Manhood Suffrage and Vote by Ballot Association. He also joined forces with a group of trade unionists that became known collectively as the "junta" urged the establishment of an international organisation. This included George Odger, Robert Applegarth, William Allan and Johann Eccarius. "The aim of the Junta was to satisfy the new demands which were being voiced by the workers as an outcome of the economic crisis and the strike movement. They hoped to broaden the narrow outlook of British trade unionism, and to induce the unions to participate in the political struggle". (5)

International Workingmen's Association

On September 28, 1864, Lucraft attended an international meeting for the reception of French trade unionists at St. Martin’s Hall in London. The meeting was organised by George Howell and attended by a wide array of radicals including Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. The historian Edward Spencer Beesly was in the chair and he advocated "a union of the workers of the world for the realisation of justice on earth". (6)

In his speech, Beesly "pilloried the violent proceedings of the governments and referred to their flagrant breaches of international law. As an internationalist he showed the same energy in denouncing the crimes of all the governments, Russian, French, and British, alike. He summoned the workers to the struggle against the prejudices of patriotism, and advocated a union of the toilers of all lands for the realisation of justice on earth." (7)

The new organisation was called the International Workingmen's Association (IWMA). Karl Marx attended the meeting and he was asked to become a member of the General Council that consisted of two Germans, two Italians, three Frenchmen and twenty-seven Englishmen (eleven of them from the building trade). Marx was proposed as President but as he later explained: "I declared that under no circumstances could I accept such a thing, and proposed Odger in my turn, who was then in fact re-elected, although some people voted for me despite my declaration." (8)

The General Council met for the first time on 5th October. George Odger was elected as President and William Cremer as Secretary. After "a very long and animated discussion" the Council could not agree on a programme. Johann Eccarius privately told Marx: "You absolutely must impress the stamp of your terse yet pregnant style upon the first-born child of the European workmen's organisation". (9)

Over the next few months other European radicals such as Wilhelm Liebknecht, August Bebel, Élisée Reclus, Ferdinand Lassalle, William Greene, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Friedrich Sorge and Louis Auguste Blanqui joined the organisation. Mikhail Bakunin was aware of the growth of the IWMA and after forming the International Alliance of Socialist Democracy, he proposed a merger between the two organisations on equal terms, where he would effectively become co-president of the IWMA. This idea was rejected but in 1868 it was agreed to allow the Alliance of Socialist Democracy to become an ordinary affiliate organisation.

Reform League

On 23rd February, 1865, Benjamin Lucraft, George Odger, George Howell, Johann Eccarius, William Cremer and several other members of the International Workingmen's Association established the Reform League, an organisation to campaign for one man, one vote. Karl Marx told Friedrich Engels "The International Association has managed so to constitute the majority on the committee to set up the new Reform League that the whole leadership is in our hands". (10)

Paul Thomas Murphy has argued that "Lucraft took his place on the militant wing of the league's executive committee, promoting continual mass agitation to achieve the goal of manhood suffrage. In April 1866 Lucraft initiated meetings on Clerkenwell Green, vowing to assemble weekly until parliament had reached a final decision on the Liberal Reform Bill. With Lucraft in the chair these meetings quickly grew in popularity. They provided Lucraft with the support of a stratum of the working class hitherto rare in Reform League demonstrations". (11)

On 2nd July 1866 the Reform League organised "a great street procession and meeting, 30,000 strong, in support of the popular demand for household suffrage... the London press for days after the procession had marched through the principal streets of the fashionable West End, teemed with half-frightened references to its military aspects, good marching, admirable order, well closed column and complete discipline." (12)

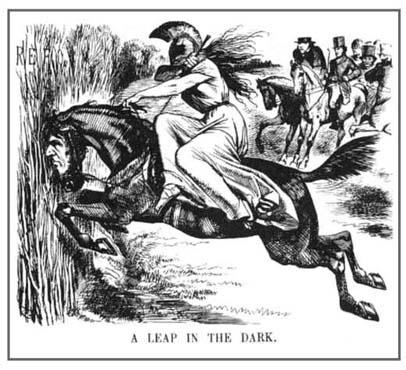

William Gladstone, the new leader of the Liberal Party, made it clear that he was in favour of increasing the number of people who could vote. Although the Conservative Party had opposed previous attempts to introduce parliamentary reform, they knew that if the Liberals returned to power, Gladstone was certain to try again. Benjamin Disraeli, leader of the House of Commons, argued that the Conservatives were in danger of being seen as an anti-reform party. In 1867 Disraeli proposed a new Reform Act. Lord Cranborne (later Lord Salisbury) resigned in protest against this extension of democracy. However, as he explained this had nothing to do with democracy: "We do not live - and I trust it will never be the fate of this country to live - under a democracy." (13)

In the House of Commons, Disraeli's proposals were supported by Gladstone and his followers and the measure was passed. The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832. (14)

In October 1869 Benjamin Lucraft helped to establish the Land and Labour League. Its formation was precipitated by discussion of the land question at the IWMA Basle Congress earlier that year. The League advocated the full nationalisation of land and was considered to be a republican working-class movement. Other members included George Odger, Charles Bradlaugh and Johann Eccarius. (15)

Schools under the control of locally elected School Boards were made possible by the 1870 Education Act. Later that year Benjamin Lucraft was elected as a member from Finsbury for the newly instituted London School Board. He was the only working-class candidate to win a seat. As a member of the board he opposed the use of the cane and campaigned against military drill in schools. He was also a leading campaigner for the introduction of a national system of free education. (16)

The IWMA gave its support to strikes taking place in Europe. The financial help given by British trade unions to the striking Paris bronze workers led to their victory. The IWMA was also involved in helping Geneva builders and Basle silk-weavers. Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel were gradually building up support for the organisation in Germany. David McLellan points out that the IWA was "steadily gaining in size, success and prestige". (17)

At first Benjamin Lucraft gave his support to the Paris Commune but was appalled by the scale of the violence. He also disagreed with the views of Karl Marx, that were expressed in The Civil War in France (1871) and along with George Odger decided to resign from the General Council of International Workingmen's Association. (18) According to Boris Nicolaevsky "as cautious and far-sighted individuals and members of royal commissions and friends of some of the very best people, had long since begun to experience a sensation of discomfort". (19)

Lucraft continued to embrace radical causes, becoming president of the Working Men's National League for the Abolition of the State Regulation of Vice and worked closely with Josephine Butler in the campaigned for the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts. He was also on the executive of the Workmen's Peace Association, which advocated international arbitration and the abolition of armed forces. He also unsuccessfully stood for parliament as a radical Liberal for Finsbury in 1874, and for Tower Hamlets in 1880, coming bottom of the poll on both occasions. (20)

In 1896 Lucraft attended a meeting of Octogenarian Teetotallers in St Martin's Hall, London. There were over forty 80-year-olds present and around 200 had actually been traced with 152 providing questionnaire answers about their lifestyle. A few months later Lucraft celebrated 50 years as a total abstainer, at a party where he was surrounded by his children, grandchildren and great grand children. (21)

Benjamin Lucraft died at his home, 18 Green Lanes, Stoke Newington, on 25th September 1897.

Primary Sources

(1) Paul Thomas Murphy, Benjamin Lucraft : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

Benjamin Lucraft worked as a ploughboy as a youth, and was indentured as an apprentice in husbandry, but also gained experience in cabinet-making, the family trade. He had established a cabinet-making workshop in Taunton by 1830 when he married, on Christmas eve, Mary Pearce. Within a year his first son was born. Soon after this the family moved to London, establishing a cabinet-making business in Shoreditch. On 27 June 1858, following the death of his first wife (with whom he had four sons and a daughter), he married at the Strand register office Mary Anne Adelaide Hitchin (1830–1877), daughter of William Hitchin, jeweller.

Little is known of Lucraft's political activities until the late 1850s, although he apparently became a Chartist in 1848, and attended the Kennington Common demonstration on 10 April 1848. Around this time he also became a confirmed advocate of temperance, and for the rest of his life he combined political and temperance activism. He chaired the annual Chartist conference in February 1858 when Ernest Jones was elected sole executive and laid out a political programme that looked away from inflexible six-point Chartism and moved towards co-operation with other supporters of parliamentary reform. Lucraft served on the executive of the organization born of this conference, the Political Reform League. During these final years of Chartism, Lucraft was active in a host of political organizations, foremost among them the North London Political Union, for which he was secretary. He took a prominent part in open-air meetings in Hyde Park and Britannia Fields, London, in 1859 and 1860, called to consider Lord John Russell's failed reform measure, honing the organizational skills that would make him a key figure during the reform agitation of 1866 and 1867.

(2) George Howell, biographical note (c. 1895)

Mr Lucraft may be described as almost the last surviving link between the old Chartist movements prior to 1850, and the newer political movements which grew out of the Chartist agitation towards the end of the fifties and onward until the Reform Act of 1884. Lucraft was one of the earliest I heard speak after coming to London, Mr Ernest Jones being the first as already stated. Often and often have I stood by Lucraft in what was then known as the Copenhagen Fields, and also in a meeting place in Chapel Street Islington. I became more closely associated with Mr Lucraft in Temperance work in 1856 and 1857, from which dates we have been old friends and close associates. He was among the first members of the Reform League and was a member of the Council and the Executive from the first. He was never a very effective speaker, but he was able always to put his points forcibly, because he knew what he wanted and could see tolerably clearly the way in which it could be obtained. In his earlier days he was thought to be an implacable Chartist, and nothing else; but he was not the man to oppose reform because all that he desired was not granted. Lucraft was sternly devoted to "principles", but he acknowledged the value of compromise when it was a question of something or nothing. He was unswerving in his advocacy of chartism and teetotalism. From 1850 to 1860 he was one of the few that kept the lingering embers of the chartist movement alive, by blowing it, so that if it did not light up very much you could still see the sparks, and feel some of its warmth. Next to chartism pure and simple, that is "the six points", he was an ardent advocate of Land Law Reform and of Technical Education...

After the dissolution of the Reform League in 1869, Lucraft became an ardent advocate of the Education policy of the National Education League, and was rewarded by being selected as on eof the candidates for, and duly elected as one of the Members of the London School Board for the Division in which he had always lived – the old Borough of Finsbury. The excellence of his work on the School Board for London is now admitted by everybody. He especially left his mark in connection with the questions of Technical Education, and the use of London Charities. Although strongly in favour of a purely secular system of education, he was a staunch supporter of the compromise arrived at in the earlier history of the Board. Mr Lucraft always took an independent view, and would not become a mere party man in all occasions.

The other question was the substitution of Arbitration in lieu of war, a Peace Policy for all nations. He was one of the first members of the Workman's Peace Association, and was for some years its chairman. Lucraft was a true and loyal colleague, in council and out of it. He would never condescend to be in cliques, though his good nature sometimes was used for such purposes. But as soon as he saw the drift he manfully resumed his independent attitude. His regularity and punctuality were proverbial. Lucraft was at his post. In the open air, at meetings, or in the Committee Room, he was on duty. I think he loved speaking for its own sake, and yet he could sit quietly and record his vote if silence was thought to be best. But "in the Park", or in Trafalgar Square, or on his own more familiar ground – Clerkenwell Green – Lucraft was always to the front, and I must add was always welcome. Lucraft was much respected for his high character in the Borough in which he lived, which was testified again and again by his repeated re-elections to the School Board for London.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)