Kurt Eisner

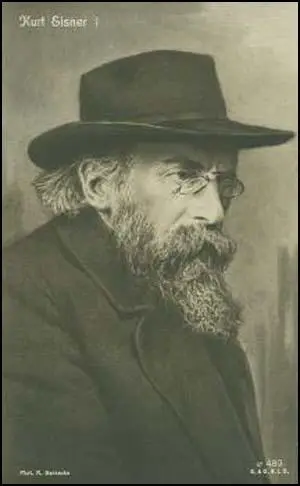

Kurt Eisner, the son of a successful Jewish businessman, was born in Berlin on 14th May, 1867. After studying literature and philosophy at Marburg he published Friedrich Nietzsche and the Apostle of the Future (1892). Later that year he married the artist, Elisabeth Hendrich. Over the next few years she gave birth to five children.

Eisner worked as a journalist in Marburg. In 1890 he became a contributing editor of the Frankfurter Zeitung. A critical article on Kaiser Wilhelm II resulted in him spending nine months in prison.

In 1898 Eisner joined the Social Democratic Party (SDP). After the death of Wilhelm Liebknecht he became editor of Der Volksstaat. The SDP was deeply divided over policy. Eduard Bernstein, a member of the SDP, became convinced that the best way to obtain socialism in an industrialized country was through trade union activity and parliamentary politics. He published a series of articles where he argued that the predictions made by Karl Marx about the development of capitalism had not come true. He pointed out that the real wages of workers had risen and the polarization of classes between an oppressed proletariat and capitalist, had not materialized. Nor had capital become concentrated in fewer hands. Bernstein's revisionist views appeared in his extremely influential book Evolutionary Socialism (1899). His analysis of modern capitalism undermined the claims that Marxism was a science and upset leading revolutionaries such as Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky. During this period Eisner was a supporter of Bernstein.

August Bebel, the leader of SDP, disagreed with Bernstein's ideas. Paul Frölich has argued: "The SPD divided into three clear tendencies: the reformists, who tended increasingly to espouse the ruling-class imperialist policy; the so-called Marxist Centre, which claimed to maintain the traditional policy, but in reality moved closer and closer to Bernstein's position; and the revolutionary wing, generally called the Left Radicals (Linksradikale)." Eisner identified with the Left Radicals. Headed by Rosa Luxemburg it included Karl Liebknecht, Clara Zetkin, Franz Mehring, Karl Radek and Anton Pannekoek. In 1905 Eisner was forced to resign as editor of the Der Volksstaat. He became chief editor for the Fränkische Tagespost in Nuremberg from 1907 to 1910 and afterwards became a freelance journalist in Munich.

On the outbreak of the First World War, the SDP leader, Friedrich Ebert, ordered members in the Reichstag to support the war effort. Karl Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the war. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy."

Eisner supported Ebert until documents were published suggesting that Wilhelm II was responsible for starting the conflict. In April 1917 left-wing members of the Social Democratic Party formed the Independent Socialist Party. Members included Eisner, Karl Kautsky, Rudolf Breitscheild, Julius Leber, Ernst Thälmann and Rudolf Hilferding. Later that year Eisner was arrested and charged with inciting a strike of munitions workers. He spent 9 months in Stadelheim Prison, before being released during the General Amnesty in October, 1918.

On 28th October, 1918, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhardt Scheer, planned to dispatch the fleet for a last battle against the British Navy in the English Channel. Navy soldiers based in Wilhelmshaven, refused to board their ships. The next day the rebellion spread to Kiel when sailors refused to obey orders. The sailors in the German Navy mutinied and set up councils based on the soviets in Russia. By 6th November the revolution had spread to the Western Front and all major cities and ports in Germany.

Eisner, the leader of the Independent Socialist Party in Munich, called for a general strike. As Paul Frölich has pointed out: "They (Eisner and his political supporters) were enthusiastic about the idea of the political strike especially because they regarded it as a weapon which could take the place of barricade-fighting, and it seemed a peaceable weapon into the bargain."

Konrad Heiden wrote: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds."

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter & Facebook, make a donation to Spartacus Education and subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Chris Harman, the author of The Lost Revolution (1982), has argued: "On 7th November, 1918, the city was paralysed by the strike. Auer (the SDP leader) turned up to address what he expected to be a peaceful demonstration, to find the most militant section of it composed of armed soldiers and sailors, gathered behind the bearded Bohemian figure of Eisner and a huge banner reading Long Live the Revolution. While the Social Democrat leaders stood aghast, wondering what to do, Eisner led his group off, drawing much of the crowd behind it, and made a tour of the barracks. Soldiers rushed to the windows at the sound of the approaching turmoil, exchanged quick words with the demonstrators, picked up their guns and flocked in behind."

Eisner led the large crowd into the local parliament building, where he made a speech where he declared Bavaria a Socialist Republic. Eisner made it clear that this revolution was different from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and announced that all private property would be protected by the new government. Eisner explained that his program would be based on democracy, pacifism and anti-militarism. The King of Bavaria, Ludwig III, decided to abdicate and Bavaria was declared a republic.

Eisner wrote in a letter dated 14th November to Gustav Landauer: "What I want from you is to advance the transformation of souls as a speaker." Others who arrived in the city to support the new regime included Erich Mühsam, Ernst Toller, Otto Neurath, Silvio Gesell and Ret Marut. Landauer became a member of several councils established to both implement and protect the revolution.

Eisner had the support of the 6,000 workers of the munitions factory in Munich that was owned by Gustav Krupp. Many of them had come from northern Germany and were much more radical than those of Bavaria. The city was also a staging post for troops withdrawing from the Western Front. It is estimated that the majority of the 50,000 soldiers also supported Eisner's revolution. The anarcho-communist poet, Erich Mühsam, and the left-wing playwright, Ernst Toller, were other important figures in the rebellion.

On 9th November, 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and the Chancellor, Max von Baden, handed power over to Friedrich Ebert, the leader of the German Social Democrat Party. At a public meeting, one of Ebert's most loyal supporters, Philipp Scheidemann, finished his speech with the words: "Long live the German Republic!" He was immediately attacked by Ebert, who was still a strong believer in the monarchy and was keen for one of the his grandsons to replace Wilhelm.

In Germany elections were held for a Constituent Assembly to write a new constitution for the new Germany. As a believer in democracy, Rosa Luxemburg assumed that her party would contest these universal, democratic elections. However, other members were being influenced by the fact that Lenin had dispersed by force of arms a democratically elected Constituent Assembly in Russia. Luxemburg rejected this approach and wrote in the party newspaper: "The Spartacus League will never take over governmental power in any other way than through the clear, unambiguous will of the great majority of the proletarian masses in all Germany, never except by virtue of their conscious assent to the views, aims, and fighting methods of the Spartacus League."

Paul Frölich has argued: "The enemies of the revolution had worked circumspectly and cunningly. On 10th November Ebert and the General Army Headquarters concluded a pact whose preliminary aim was to defeat the revolution. During that month there were bloody clashes between workers. During this month there were bloody clashes between workers and returning front-line soldiers who had been stirred up by the authorities. On military drill-grounds special troops, in strict isolation from the civilian population, were being ideologically and militarily trained for civil war."

On 29th December, 1918, Friedrich Ebert gave permission for the publishing of a Social Democratic Party leaflet that attacked the activities of the Spartacus League, led by Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Leo Jogiches and Clara Zetkin: "The shameless doings of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg besmirch the revolution and endanger all its achievements. The masses cannot afford to wait a minute longer and quietly look on while these brutes and their hangers-on cripple the activity of the republican authorities, incite the people deeper and deeper into a civil war, and strangle the right of free speech with their dirty hands. With lies, slander, and violence they want to tear down everything that dares to stand in their way. With an insolence exceeding all bounds they act as though they were masters of Berlin."

In Bavaria Eisner was forced to form a coalition government with the Social Democratic Party. During this period the living conditions of the Munich workers and soldiers were rapidly deteriorating. It was not a surprise when at the election on 12th January, 1919, in Bavaria, Eisner and the Independent Socialist Party received only 2.5 per cent of the total vote.

Eisner remained in power by granting concessions to the SDP. This included agreeing to the establishment of a regular security force to maintain order. As Chris Harman pointed out: "In office without any power base of his own, he was forced to behave in an increasingly arbitrary and apparently irrational manner". On 21st February, 1919, Eisner decided to resign. On his way to parliament he was assassinated by Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley. It is claimed that before he killed the leader of the ISP he said: "Eisner is a Bolshevist, a Jew; he isn't German, he doesn't feel German, he subverts all patriotic thoughts and feelings. He is a traitor to this land."

Konrad Heiden wrote in his biography of Adolf Hitler: "Like Lenin, he had the peasants and workers on his side, but all the educated classes, the officers, officials, students, against him; in such a case there is no difference between Christian and Jew. Belatedly the intellectuals grew ashamed of their cowardice; they grew ashamed when they perceived that there was no danger. Their radical hatred found its embodiment in leagues like the Thule Society. While the Rosenbergs, the Hesses, the Eckarts, and others whose names have been forgotten were still planning - such an act, after all, was dangerous - a man whom they had insulted and cast aside got ahead of them. The League had rejected Count Anton Arco-Valley, a young officer, for being of Jewish descent on one side. Determined to shame his insulters by an example of courage, he shot Eisner down in the midst of his guards on the open street. A second later he himself lay on the ground, with a bullet through his chest. Eisner's secretary, Fechenbach, sprang forward and saved the assassin from being trampled by the boots of the infuriated soldiers. A mass insurrection broke out, a soviet republic was proclaimed."

The novelist, Heinrich Mann, a supporter of the Independent Socialist Party, spoke at Eisner's funeral and at his memorial three weeks later. Thomas Mann, who was deeply opposed to socialism, commented that Heinrich claimed that "Eisner had been the first intellectual at the head of a German state... in a hundred days he had had more creative ideas than others in fifty years, and... had fallen as a martyr to truth. Nauseating!"

Primary Sources

(1) Kurt Eisner, Die Neue Zeit (1914)

Who in Germany exercises the decisive influence upon the course of foreign policy? For a quarter of a century none but the Pan-Germans. They have attained a greater influence on the direction of policy than even the powerful associations of landlords and capitalists. In the course of this time they have achieved more than all the political parties and all the parliamentary groups in Germany put together. From the first naval measure to the last army bill, all the armament plans originated in the circles of the Pan-Germans. They were the shock troops.

(2) Konrad Heiden, Der Führer – Hitler's Rise to Power (1944)

Now the Thule Society prepared to act. They decided to kill Premier Eisner. Kurt Eisner was a Socialist writer, the leader of the Bavarian Revolution. On November 6, 1918, he was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds. When the news came the Minister of War cried out: "Revolution, oh, my God, and here I am, still in uniform!"Unlike Lenin, Eisner really was a Jew. Like Lenin, he had the peasants and workers on his side, but all the educated classes, the officers, officials, students, against him; in such a case there is no difference between Christian and Jew. Belatedly the intellectuals grew ashamed of their cowardice; they grew ashamed when they perceived that there was no danger. Their radical hatred found its embodiment in leagues like the Thule Society. While the Rosenbergs, the Hesses, the Eckarts, and others whose names have been forgotten were still planning - such an act, after all, was dangerous - a man whom they had insulted and cast aside got ahead of them. The League had rejected Count Anton Arco-Valley, a young officer, for being of Jewish descent on one side. Determined to shame his insulters by an example of courage, he shot Eisner down in the midst of his guards on the open street. A second later he himself lay on the ground, with a bullet through his chest. Eisner's secretary, Fechenbach, sprang forward and saved the assassin from being trampled by the boots of the infuriated soldiers. A mass insurrection broke out, a soviet republic was proclaimed. The Communists seized power-without bloodshed. In the place where Eisner fell, his picture was pasted to the wall; a Red Army man stood beside it, and all passers-by had to salute the picture. The members of the Thule Society soaked a bag of flour in the sweat of two bitches in heat, someone "accidentally" dropped the bag in front of the picture, the flour clung to the ground and the walls; dogs gathered by the dozens, the picture and the guards silently vanished. This repulsive story is told here only because those responsible publicly boasted of it.

An army marched against revolutionary Munich. It was a motley troop: remnants of disbanding regiments; free corps, newly formed of unemployed soldiers and young people eager for adventure. In a village south of Munich a labour battalion of Russian war prisoners, forgotten though peace had been signed with Russia months before, fell into their hands. Russians? Must be Bolsheviki. What else would they be? Fifty-three Russian prisoners met their death in a sandpit over this misapprehension. In another village a lieutenant asked the priest on whom he was billeted if he didn't know a few Red suspects in his community. Oh, yes, he knew some, and he named twelve, all of whom, as came to light in a later trial, were quite harmless individuals, who in the troubled times had somehow frightened the priest. On its march the troop dragged along twelve workers, drove them into the courtyard of the Munich slaughter-house, and shot them against a wall with several hundred other unfortunates. The slaughter lasted for several days.

(3) Chris Harman, The Lost Revolution (1982)

On 7th November, 1918, the city was paralysed by the strike. Auer (the SDP leader) turned up to address what he expected to be a peaceful demonstration, to find the most militant section of it composed of armed soldiers and sailors, gathered behind the bearded Bohemian figure of Eisner and a huge banner reading Long Live the Revolution. While the Social Democrat leaders stood aghast, wondering what to do, Eisner led his group off, drawing much of the crowd behind it, and made a tour of the barracks. Soldiers rushed to the windows at the sound of the approaching turmoil, exchanged quick words with the demonstrators, picked up their guns and flocked in behind.