Tank Development

Richard Lovell Edgeworth invented the Caterpillar track in 1770. In the Crimean War a small number of steam powered tractors based on this design proved very successful in the muddy terrain. He played around with for forty years but that he never successfully developed. He described it as a "cart that carries its own road". (1)

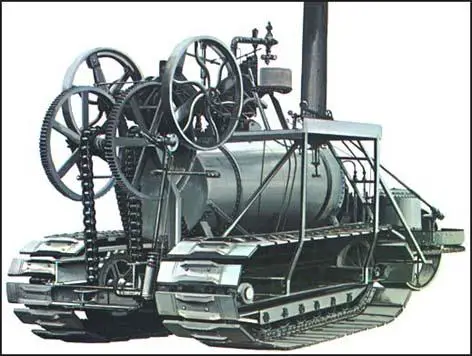

The development of the modern tank remained dormant until the arrival of the internal combustion engine, patented by Gottlieb Daimler in 1885. In the United States the Holt Company built a tractor with caterpillar tracks that was used to move over difficult territory. Although it was suggested that this machine might be adapted for military use, those in positions of authority failed to see the significance of this new development. (2)

In 1899 Frederick Richard Simms produced a design of what he called a motor-war car. This vehicle had a Daimler engine, a bulletproof shell and was armed with 2 maxim guns on revolving turrets. It was the first armoured car ever built. The British War Office rejected Simms' car and showed no interest in similar schemes. (3)

Colonel Ernest Swinton

The idea of an armoured tracked vehicle that would provide protection from machines gun fire was first discussed by army officers in 1914. Two of the officers, Colonel Ernest Swinton and Colonel Maurice Hankey, both became convinced that it was possible to develop a fighting vehicle that could play an important role in any future war. On the outbreak of the First World War Colonel Swinton was sent to the Western Front to write reports on the war. After observing early battles where machine-gunners were able to kill thousands of infantryman advancing towards enemy trenches, Swinton wrote that "petrol tractors on the caterpillar principle and armoured with hardened steel plates" would be able to counteract the machine-gunner. (4)

To maintain secrecy, Swinton coined the euphemism "tank", to describe the new weapon. However, he faced real problems from his boss, Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State of War. His style of leadership was very authoritarian and was reluctant to experiment. Swinton later argued that after putting the idea to Kitchener without getting any support he hesitated to press too hard because he dreaded a direct order to drop it. (5)

Churchill became very interested in this project and according to Boris Johnson, the author of The Churchill Factor (2014) he became part of the development team. He suggested that an experiment should be performed. He suggested that they should "take two steam rollers and yoke them together with long steel rods... so that they are to all intents and purposes one roller covering a breadth of at least 12 to 14 feet." Johnson argues that "this is Churchill at his dizzing best... An idea was being born. Perhaps without even knowing it, he was describing caterpillar tracks". (6)

Richard Hornsby & Sons also worked on the project and eventually produced the Killen-Strait Armoured Tractor. The tracks consisted of a continuous series of steel links, joined together with steel pins. In June 1915 the Killen-Strait was tested out in front of Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George at Wormwood Scrubs. The machine successfully cut through barbed wire entanglements. Churchill became convinced that this new machine would enable trenches to be crossed quite easily. (7)

Colonel Ernest Swinton persuaded the newly-formed Inventions Committee to spend money on the development of a small land-ship. and drew up specifications for this new machine. This included: (i) a top speed of 4 mph on flat ground; (ii) the capability of a sharp turn at top speed; (iii) a reversing capability; (iv) the ability to climb a 5-foot earth parapet; (v) the ability to cross a 8-foot gap; (vi) a vehicle that could house ten crew, two machine guns and a 2-pound gun. Winston Churchill wrote to H. H. Asquith, the prime minister about Swinton's ideas. (8)

In February 1915, Churchill arranged for the Admiralty to spend £70,000 on building an experimental "land ship" (Swinton insisted on calling them tanks). A month later Churchill agreed that eighteen prototypes should be built (six were to have wheels and twelve tracks). However, most of the major work was undertaken by the War Office and Ministry of Munitions. (9)

Little Willie

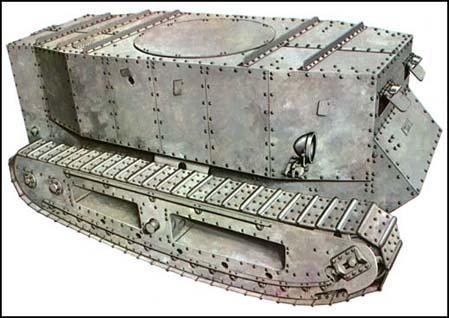

The first tank developed was given the nickname Little Willie. This prototype tank with its Daimler engine, had track frames 12 feet long, weighed 14 tons and could carry a crew of three, at speeds of just over three miles. The speed dropped to less than 2 mph over rough ground and most importantly of all, was unable to cross broad trenches. Although the performance was disappointing, Colonel Swinton remained convinced that when modified, the tank would enable the Allies to defeat the Central Powers. (10)

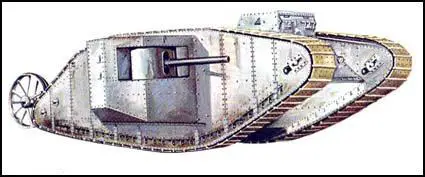

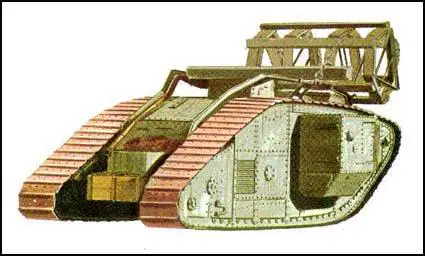

The production of Little Willie by Lieutenant Walter G. Wilson and William Tritton in the late summer of 1915 revealled several technical problems. The two men immediately began work on an improved tank. Mark I, nicknamed Mother, was much longer than the first tank they made. This kept the centre of gravity low and the extra length helped the tank grip the ground. Sponsons were also fitted to the sides to accommodate two naval 6-pound guns. In trials carried out in January 1916 the tank crossed a 9ft. wide trench with a 6ft. 6in. parapet and convinced watchers of its "obstacle-crossing ability". (11)

it was decided to demonstrate the new tank to Britain's political and military leaders. Under conditions of great secrecy, Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State of War, David Lloyd George, Minister of Munitions, and Reginald McKenna, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, were invited to Hatfield Park on 2nd February, 1916 to see Mark I in action. Lord Kitchener was unimpressed describing tanks as "mechanical toys" and asserting that "the war would never be won by such machines". Although without military experience, Lloyd George and McKenna saw their potential and placed an order for a 100 tanks. (12)

According to Colonel Charles Repington, that the government's greatest advocate of tanks, Winston Churchill, "wanted them to wait until there were something like a thousand Tanks, and then to win a great battle with them as a surprise". (13) This was acceptable to Sir Douglas Haig, Commander-in Chief of the British Army, as he had doubts about the value of tanks. However, after failing to break through German lines at the Battle of the Somme, Haig gave orders that tanks that had reached the Western Front, should be used at Flers-Coucelette on 15th July, 1916. (14)

It was not until 28th September, 1916, that the newspapers were allowed to report the use of tanks on the Western Front in France. The Manchester Guardian reported: "The British army has struck the enemy another heavy blow north of the Somme... Armoured cars (tanks) working with the infantry were the great surprise of this attack. Sinister, formidable, and industrious, these novel machines pushed boldly into No Man's Land, astonishing our soldiers no less than they frightened the enemy." (15)

The Daily Chronicle also carried news of tanks that day. "Over our own trenches in the twilight of the dawn those motor-monsters had lurched up, and now it came crawling forward to the rescue, cheered by the assaulting troops, who called out words of encouragement to it and laughed, so that some men were laughing even when bullets caught them in the throat. 'Creme de Menthe' was the name given to this particular creature, and it waddled forward right over the old German trenches. There was a whip of silence from the enemy. Then, suddenly, their machine-gun fire burst out in nervous spasms and splashed the sides of 'Creme de Menthe'. But the tank did not mind. The bullets fell from its sides harmlessly. From its sides came flashes of fire and a hose of bullets, and then it trampled around over machine emplacements 'having a grand time', as one of the men said with enthusiasm. It crushed the machine-guns under its heavy ribs, and killed machine-gun teams with deadly fire. The infantry followed in and took the place after this good help, and then advanced again round the flanks of the monster." (16)

In reality, the tanks were not a great success the first time they were used. Of the 59 tanks in France, only 49 were considered to be in good working order. Of these, 17 broke down on the way to their starting point at Flers. The sight of the tanks created panic and had a profound effect on the morale of the German Army. Colonel John Fuller, chief of staff of the Tank Corps, was convinced that these machines could win the war and persuaded Sir Douglas Haig to ask the government to supply him with another 1,000 tanks. Basil Liddell Hart argues the main problem was that "Swinton's memorandum laid down a number of conditions which were disregarded in September, 1916... The sector for tank attack was to be carefully chosen to comply with the powers and limitations of the tanks." (17)

Tanks in 1917-1918

The third major battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, took place between July and November, 1917. General Haig, the British Commander in Chief in France, was encouraged by the gains made at the offensive at Messines. Haig was convinced that the German army was now close to collapse and once again made plans for a major offensive to obtain the necessary breakthrough. The official history of the battle claimed Haig's plan "may seem super-optimistic and too far-reaching, even fantastic". Many historians have suggested that the main problem was that Haig "had chosen a field of operations where the preliminary bombardment churned the Flanders plain into impassable mud." (18)

The opening attack at Passchendaele was carried out by General Hubert Gough and the British Fifth Army with General Herbert Plumer and the Second Army joining in on the right and General Francois Anthoine and the French First Army on the left. After a 10 day preliminary bombardment, with 3,000 guns firing 4.25 million shells, the British offensive started at Ypres a 3.50 am on 31st July.

Allied attacks on the German front-line continued despite very heavy rain that turned the Ypres lowlands into a swamp. The situation was made worse by the fact that the British heavy bombardment had destroyed the drainage system in the area. This heavy mud created terrible problems for the infantry and the use of tanks became impossible. Percival Phillips of The Daily Express commented: "The weather changed for the worse last night, although fortunately too late to hamper the execution of our plans. The rain was heavy and constant throughout the night. It was still beating down steadily when the day broke chill and cheerless, with a thick blanket of mist completely shutting off the battlefield. During the morning it slackened to a dismal drizzle, but by this time the roads, fields, and footways were covered with semi-liquid mud, and the torn ground beyond Ypres had become in places a horrible quagmire." (19)

After the failure of British tanks in the thick mud at Passchendaele, Colonel John Fuller, chief of staff to the Tank Corps, suggested a massed raid on dry ground between the Canal du Nord and the St Quentin Canal. General Sir Julian Byng, commander of the Third Army, accepted Fuller's plan, although it was originally vetoed by the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig. However, he changed his mind and decided to launch the Cambrai Offensive. (20)

Haig, who was not given this information, ordered a massed tank attack at Artois. Launched at dawn on 20th November, without preliminary bombardment, the attack completely surprised the German Army defending that part of the Western Front. Employing 476 tanks, six infantry and two cavalry divisions, the British Third Army gained over 6km in the first day. It was claimed that the use of tanks in the battle was very effective. "Tanks and cavalry co-operated in this attack, and the tanks were a most powerful aid, and cruised round and through the village, where they put out nests of machine-guns." (21)

However, Philip Gibbs of the Daily Chronicle claimed that tanks were still encountering problems: "We thought these tanks were going to win the war, and certainly they helped to do so, but there were too few of them, and the secret was let out before they were produced in large numbers. Nor were they so invulnerable as we had believed. A direct hit from a field gun would knock them out, and in our battle for Cambrai in November of 1917 I saw many of them destroyed and burnt out." (22)

Progress towards Cambrai continued over the next few days but on the 30th November, 1917, twenty-nine German divisions launched a counter-offensive. This included the use of mustard gas. One of the nurses, Vera Brittain, explained to her mother about the impact of these attacks. "We have heaps of gassed cases at present : there are 10 in this ward alone. I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war, and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case - to say nothing of 10 cases of mustard gas in its early stages - could see the poor things all burnt and blistered all over with great suppurating blisters, with blind eyes - sometimes temporally, some times permanently - all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, their voices a whisper, saying their throats are closing and they know they are going to choke." (23)

By the time that fighting came to an end on 7th December, 1917, German forces had regained almost all the ground it lost at the start of the Cambrai Offensive. During the two weeks of fighting, the British suffered 45,000 casualties. Although it is estimated that the Germans lost 50,000 men, Sir Douglas Haig considered the offensive as a failure and reinforced his doubts about the ability of tanks to win the war. (24)

Allied casualties during the 2nd Battle of the Marne were heavy: French (95,000), British (13,000) and United States (12,000). The Allies also captured 609 German officers and 26,413 enlisted men, 612 enemy artillery pieces and 3,300 machine guns. It is estimated that the German Army suffered an estimated 168,000 casualties and marked the last real attempt by the Central Powers to win the First World War. (25)

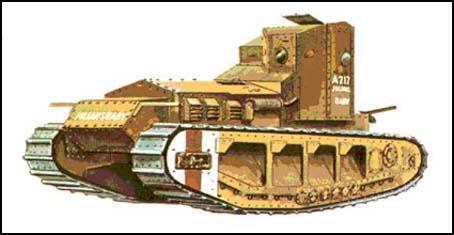

The Allied Supreme Commander, Ferdinand Foch now ordered a counter-offensive. Foch put British Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig in overall charge of the offensive and he selected General Sir Henry Rawlinson and the British Fourth Army to lead the attack. The Amiens offensive took place on 8th August 1918. Every available tank was moved to Rawlinson's sector. This included 72 Whippet and 342 Mark V tanks. Rawlinson also had 2,070 artillery pieces and 800 aircraft. The German sector chosen was defended by 20,000 soldiers and were outnumbered 6 to 1 by the attacking troops. The tanks followed by soldiers met little resistance and by mid morning allied forces had advanced 12km. The Amiens line was taken, and later, General Erich Ludendorff, the man in overall charge of German military operations, described the 8th August as "the black day of the German Army in the history of the war". (26)

Primary Sources

(1) Philip Gibbs was a journalist who reported the war on the Western Front.

It was the coming of the tanks that helped us to victory in the First World War. Many men claimed the honour of it. General Swinton established his claim and Winston Churchill was one of those to whom honour is due as patron if not part author.

It is impossible to revive the extraordinary thrill and amazement, the hilarious exultation with which these things were first seen on the fields of the Somme. It had been a secret, marvellously hidden. We war correspondents, who came to hear of most things in one way or another, had not heard a whisper about it until a few days before these strange things went into action.

(2) On 16th September 1916, Colonel Sir Maurice Hankey wrote in his diary about the tanks that were about to be used at the Battle of the Somme.

We drove on to see the 'caterpillars' of which we found about sixty-two, painted in grotesque colours. While we were there a German areoplane, flying at a great height, came overhead and the whole of the tanks took cover under trees or were covered with tarpaulins painted to resemble haystacks.

In the evening at dinner, I tackled both the chief of staff, and the sub-chief, about the 'caterpillars'. My thesis is that it is a mistake to put them into the battle of the Somme. They were built for the purpose of breaking an ordinary trench system with a normal artillery fire only, whereas on the Somme they will have to penetrate a terrific artillery barrage, and will have to operate in a broken country full of shell-craters, where they will be able to see very little.

(3) Charles Repington, diary entry (21st September 1916)

Lunched with Lady Cunard, Winston Churchill, Lord and Lady Frederick Blackwood, and Lieutenant Hermann of the French War Office. We had a great discussion about the famous Tanks, which made their first appearance in the field in last Friday's battle. Winston said that though he had in his mind H. G. Wells's predictions about them, they really developed from the armoured motor car, which trench warfare had rendered useless. They were taken up by the Admiralty. He found that he had some money to spare, and he applied it to this purpose. To that extent the initiative and responsibility rested with him. Winston had wanted them to wait until there were something like a thousand Tanks, and then to win a great battle with them as a surprise, but, as Northcliffe said the other day, nothing keeps whether in journalism or in war.

(4) The Great World War: Volume VI (1919)

Although the advance was not unexpected, it proved a day of dreadful surprise for the Germans. They had taught the Allies so many fearsome tricks of modern warfare that they regarded almost as an impertinence the mechanical monsters which now came lolloping from the British front; land Dreadnoughts which took shell-holes and trenches in their stride as though to the manner born, spreading death from armour-plated sides, and crushing everything which barred their passage like veritable juggernauts.

Yet the fundamental idea of the "Tanks", as the new armoured cars were called, was almost as old as the hills, even without the wooden horse of Troy. Rhodes was besieged some six centuries before Christ by a king of Asia whose son invented what was called the Helepolis - a movable wooden fort nine stories high, plated with iron, and manned by archers. The new machines were not so much armoured cars as forts on wheels, but of extraordinary mobility. Mr. H. G. Wells, who so vividly anticipated the war in the air, foretold them in his short story, The Land Ironclads; and many people had a hand in the elaboration of the idea in the form in which it took shape in the Somme offensive.

It was not until some months after the Germans had been introduced to these land cruisers that the War Office permitted any details, or illustrations of them, to be published. In due course, however, official photographs were issued, and discreet details given of their general appearance.

(5) In his diary, Private Charles Cole, described his first encounter with tanks on the Western Front.

Something was brought near to the reserve trench camouflaged with a big sheet. We were very curious and the Captain said, "Your are wondering what this is. Well, it is a tank", and then he took the covers off and that was the very first tank. When we made the next attack we had to wait for the tank to go by us and all we had to do was to mop up.

'Well, we were at the parapets, waiting for the tank. We heard the chunk, chunk, chunk, then silence! The tank never came. Well, we went over the top and we got cut to pieces because the plan had failed. Eventually the tank got going and went past us. The Germans ran for their lives. So the tank went on, knocking down brick walls, houses down, did what it was supposed to have done - but too late! We lost thousands and thousands of men."

(6) The Manchester Guardian (18th September 1916)

The British army has struck the enemy another heavy blow north of the Somme. Attacking shortly after dawn yesterday morning on a front of more than six miles north-east from Combles, it now occupies a new strip of reconquered territory including three fortified villages behind the German third line and many local positions of great strength…

Armoured cars (tanks) working with the infantry were the great surprise of this attack. Sinister, formidable, and industrious, these novel machines pushed boldly into "No Man's Land," astonishing our soldiers no less than they frightened the enemy. Presently I shall relate some strange incidents of their first grand tour in Picardy, of Bavarians bolting before them like rabbits and others surrendering in picturesque attitudes of terror, and the delightful story of the Bavarian colonel who was carted about for hours in the belly of one of them like Jonah in the whale, while his captors slew the men of his broken division.

(7) Percival Phillips, Daily Express (18th September, 1916)

Sinister, formidable, and industrious, these novel machines pushed boldly into No Man's Land, astonishing our soldiers no less than they frightened the enemy.

(8) The Daily Chronicle (18th September, 1916)

Over our own trenches in the twilight of the dawn those motor-monsters had lurched up, and now it came crawling forward to the rescue, cheered by the assaulting troops, who called out words of encouragement to it and laughed, so that some men were laughing even when bullets caught them in the throat. 'Creme de Menthe' was the name given to this particular creature, and it waddled forward right over the old German trenches.

There was a whip of silence from the enemy. Then, suddenly, their machine-gun fire burst out in nervous spasms and splashed the sides of 'Creme de Menthe'. But the tank did not mind. The bullets fell from its sides harmlessly. From its sides came flashes of fire and a hose of bullets, and then it trampled around over machine emplacements 'having a grand time', as one of the men said with enthusiasm. It crushed the machine-guns under its heavy ribs, and killed machine-gun teams with deadly fire. The infantry followed in and took the place after this good help, and then advanced again round the flanks of the monster.

In spite of the tank, which did grand work, the assault on Courcelette was hard and costly. Again and again the men came under machine-gun fire and rifle fire, for the Germans had dug new trenches which had not been wiped out by our artillery.

These soldiers our ours were superb in courage and stoic endurance, and pressed forward steadily in broken waves. The first news of success came through the airman's wireless, which said: "A tank is walking up the high street of Flers with the British army cheering behind."

(9) William Beach Thomas, With the British at the Somme (1917)

They (the tanks) looked like blind creatures emerging from the primeval slime. To watch one crawling round a battered wood in the half-light was to think of "the Jabberwock with eyes of flame" who "came whiffling through the tulgey wood and burbled as it came."

(10) Major William Henry Lowe Watson was in charge of the 11th Company of the Tank Corps. Watson later wrote about his experiences in his book A Company of Tanks (1920)

Bernstein's tank was within reach of the German trenches when a shell hit the cab, decapitated the driver, and exploded in the body of the tank. The corporal was wounded in the arm, and Bernstein was stunned and temporarily blinded. The tank was filled with fumes. As the crew were crawling out, a second shell hit the tank on the roof.

Birkett went forward at top speed, and, escaping the shells, entered the German trenches, where his guns did great execution. The tank was hit twice, and all the crew were wounded, but Birkett went on fighting grimly until his ammunition was exhausted and he himself was badly wounded in the leg. Then at last he turned back. Near the embankment he stopped the tank to take his bearings. As he was climbing out, a shell burst against the side of the tank and wounded him again in the leg. The tank was evacuated. Birkett was brought back on a stretcher, and wounded a third time as he lay on the sunken road outside the dressing station.

Skinner came right to the edge of an enormous crater and stopped. He tried to reverse, but he could not change gear. The tank was absolutely motionless. The Germans brought up a gun and began to shell the tank. Against field guns he was defenceless if he could not move. With great skill he evacuated his crew, taking his guns with him and the little ammunition that remained.

Swears, the section commander, left the railway embankment, and with the utmost gallantry went forward to look for Skinner. He never came back.

Such were the cheerful reports that I received in my little brick shelter by the cross-roads.

(11) The Illustrated London News (9th December 1916)

From a German communication trench had been dug a number of small trenches mostly composed of joining up shellholes, the whole providing a system of considerable strength, which would undoubtedly have cost our infantry appreciable loss, had not one of our tanks quite unexpectedly appeared on the skyline and come lumbering towards the little strong point. The enemy holding the strong point had, of course, never seen or heard of such a thing as a tank. Panic evidently seized them and a number, losing their heads completely, started running. Above the noise of the bursting shells, the machine-guns of the tank were heard to open, seemingly simultaneously. In less time than it takes to tell, the Boches had ceased to run; they all seemed to go over like shot rabbits. The tank never paused but went straight on over the trenches, firing right and left as it did so.