Matthew Brady

Matthew Brady was born in Warren County, in about 1823 (the exact place and year is not known). As a young man Brady moved to New York City and became a jewel-case manufacturer. Soon afterwards Brady met the inventor Samuel Morse who taught him about the daguerreotype process. In 1843 Brady began making special cases for daguerreotypes and the following year opened the Daguerreotype Miniature Gallery in New York.

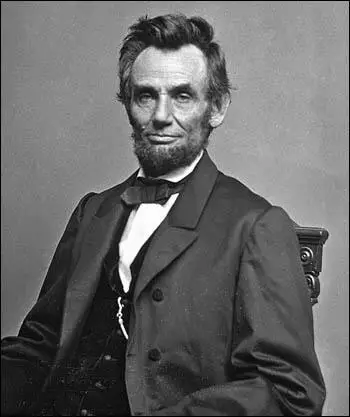

In 1844 Brady opened a gallery in Washington and began his Illustrious Americans project. This included taking the portraits of people such as Abraham Lincoln, Stephen Douglass, Thaddeus Stevens, John Calhoun, Daniel Webster, Horace Greeley, Edwin Stanton, Charles Sumner and William Seward. Brady sent twenty of these daguerreotypes to the Great Exhibition in London, where he won a medal for his achievements.

Brady toured Europe in 1851 but when he returned he found his failing eyesight made taking photographs very difficult. He began to rely heavily on his chief assistant, Alexander Gardner, who was a leading expert in the new collodion (wet-plate process) that was rapidly displacing the daguerreotype.

Gardner specialized in making what became known as Imperial photographs. These large prints (17 by 20 inches) were very popular and Brady was able to sell them for between $50 and $750, depending on the amount of retouching with india ink that was required. In the 1850s Brady's eyesight became so bad that Gardner ran his business. In February, 1858, Gardner was put in charge of Brady's gallery in Washington. He quickly developed a reputation as an outstanding portrait photographer. He also trained the young apprentice photographer, Timothy O'Sullivan.

A supporter of the Republican Party, Brady made 35 portraits of Abraham Lincoln during the 1860 presidential campaign. After his victory Lincoln told friends that "Brady and the Copper Union speech made me President."

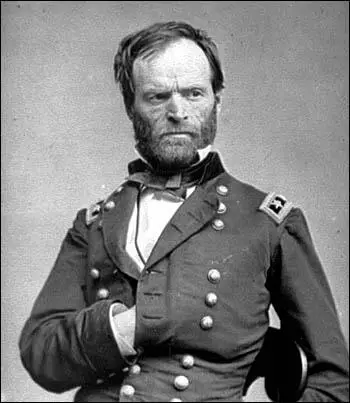

On the outbreak of the American Civil War there was a dramatic increase in the demand for work at Brady's studios as soldiers wanted to be photographed in uniform before going to the front-line. The following officers in the Union Army were all photographed at the Matthew Brady Studio: Nathaniel Banks, Don Carlos Buell, Ambrose Burnside, Benjamin Butler, George Custer, David Farragut, John Gibbon, Winfield Hancock, Samuel Heintzelman, Joseph Hooker, Oliver Howard, David Hunter,John Logan, Irvin McDowell, George McClellan, James McPherson, George Meade, David Porter, William Rosecrans, John Schofield, William Sherman, Daniel Sickles, George Stoneman, Edwin Sumner, George Thomas, Emory Upton, James Wadsworth and Lew Wallace.

In July, 1861 Brady and Alfred Waud, an artist working for Harper's Weekly, travelled to the front-line and witnessed Bull Run, the first major battle of the war. The battle was a disaster for the Union Army and Brady came close to being captured by the enemy.

Soon after arriving back from the front Brady decided to make a photographic record of the American Civil War. He sent Alexander Gardner, James Gardner, Timothy O'Sullivan, William Pywell, George Barnard, and eighteen other men to travel throughout the country taking photographs of the war. Each one had his own travelling darkroom so that that collodion plates could be processed on the spot. This included Gardner's famous President Lincoln on the Battlefield of Antietam and Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter (1863).

Brady spent most of the time organizing his cameramen from his office in Washington. However, Brady did take photographs at Bull Run. One observer claimed that Brady at Bull Run showed "more pluck than many of the officers and soldiers who were in the fight." He photographed the retreat and another witness pointed out that Brady "has fixed the cowards beyond the possibility of a doubt."

During the American Civil War Brady spent over $100,000 in obtaining 10,000 prints. He expected the government to buy the photographs when the war ended. When the government refused to do this he was forced to sell his New York City studio and go into bankruptcy.

Congress granted Brady $25,000 in 1875 but he remained deeply in debt. Depressed by his financial situation, Matthew Brady became an alcoholic and died the charity ward of Presbyterian Hospital in New York on 15th January, 1896.

Primary Sources

(1) Article about Matthew Brady's work in the Photographic Art Journal (1851)

Mr. Brady is not operating himself, a failing eyesight precluding the possibility of his using the camera with any certainty. But he is an excellent artist, nevertheless, understands his business perfectly, and gathers about him the finest talent to be found. Brady's proverbial enterprise is not to be questioned and his gallery is the most fashionable in the city.

(2) Advert in the Washington Daily National Intelligencer (26th January, 1858)

M. B. Brady respectfully announces that he has established a Gallery of Photographic Art in Washington. he is prepared to execute commissions for the Imperial Photograph, hitherto made only at his well-known establishment in New York. A variety of unique and rare photographic specimens are included in his collection, together with portraits of many of the most distinguished citizens of the United States.

(3) Photographic Art Journal (August, 1861)

Brady, the irrepressible photographer, who like the war horse, sniffs the battle from afar. He got as far as the smoke of Bull Run and was aiming his nevertheless tube at friends and foe alike, when with the rest of our Grand Army they were completely routed and took to their heels, losing their photographic accouterments on the ground, which the Rebels no doubt pounced upon as trophies of victory. Perhaps they considered the camera as an infernal machine. The soldiers live to fight another day, our special friends to make again their photographs. When will photographers have another chance in Virginia.

(4) A review of the exhibition of the photographs of Peninsula Campaign called Scenes and Incidents appeared in the New York World in July, 1862.

Brady's Photographic Corps, heartily welcomed in each of our armies, has been a feature as distinct and omnipresent as the corps of balloon, telegraph, and signal operators. They have threaded the weary stadia of every march; have hung on the the skirts of every battle scene; have caught the compassion of the hospital, the romance of the bivouac, the pomp and panoply of the field review.

(5) The New York Times on an exhibition of photographs taken by Matthew Brady, Alexander Gardner , James Gardner, George Barnard and Timothy O'Sullivan (21st July, 1862)

Brady's artists have accompanied the army on nearly all its marches, planting their sun batteries by the side of our Generals' more deathful ones, and taking towns, cities and forts with much less noise and vastly more expedition. The result is a series of pictures christened Incidents of War, and nearly as interesting as the war itself: for they constitute the history of it, and appeal directly to the great throbbing hearts of the north.

(6) After seeing the photographs taken by Alexander Gardner at of the battle at Antietam, the writer, Oliver Wendell Holmes recorded his views on the nature of war.

Let him who wishes to know what war is look at this series of illustrations. It is so nearly like visiting the battlefield to look over these views that all the emotions excited by the actual sight of the stained and sordid scene, stewed with rags and wrecks, come back to us, and we buried them in the recesses of our cabinet as we would have buried the mutilated remains of the dead they too vividly represented. The sight of these pictures is a commentary on civilization such as the savage might well triumph to show its missionaries.

(7) The New York Times on the photographs of Matthew Brady (20th October, 1862)

Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them on our dooryard and along the streets, he has done something very like it. It seems somewhat singular that the same sun that looked down on the faces of the slain, blistering them, blotting out from the bodies all the semblance to humanity, and hastening corruption, should have thus caught their features upon canvas, and given them perpetuity for ever.