The General Strike

In early 1914 the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) and the National Transport Workers' Federation (later the Transport & General Workers Union) had several meetings. In April the three unions announced that they had decided to form a Triple Industrial Alliance. It was a step toward "one-big-union" and toward industrial action of such a "magnitude that it could pose a straightforward challenge to State power." (1)

George Dangerfield, the author of The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935) wrote: "In July, the coal-owners declared that they could no longer pay their district minimum day-wage of 7s. - that they would be obliged to reduce it, in most localities, to 6s. To the miners' rank and file this was the final challenge. It was evident that the Miners' Federation of Great Britain would take issue with the Scottish coal-owners; that the transport workers and railwaymen would join in; and that - in September or, at latest, October - there would be an appalling national struggle over the question of the living wage." (2)

The strike did not take place because of the outbreak of the First World War. It was very important for the government to avoid strikes during the war and with the help of the Labour Party and the Trade Union Congress an "Industrial Truce" was announced. A further agreement in March 1915, committed the unions for the duration of hostilities to the abandonment of strike action and the acceptance of government arbitration in disputes. In return the government announced its limitation of profits of firms engaged in war work, "with a view to securing that benefits resulting from the relaxation of trade restrictions or practices shall accrue to the State". (3)

In January 1921, Arthur J. Cook, the left-wing union leader from South Wales became a member of the executive of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB). "A month later the decontrol of the mining industry was announced, with a consequent end to a national wages agreement and wage reductions. A three-month lock-out from April 1921 ended in defeat for the miners; at its end Cook was again gaoled for two months' hard labour for incitement and unlawful assembly". (4)

In 1922 Herbert Smith was elected as president of the MFGB. At a Special Conference on 18th March, Smith and Frank Hodges, general secretary of the MFGB, favoured a temporary return to district agreements so that area associations would be free to negotiate the best terms possible. However, Arthur J. Cook, called for national negotiations. Smith was outvoted and commented that this was "a declaration of war" against the colliery owners. (5)

Frank Hodges, general secretary of the MFGB was elected for Litchfield in the 1923 General Election. Under the rules of the union he now had to resign his post but he initially refused. It was not until he was appointed as Civil Lord of the Admiralty in the Labour Government that he agreed to go. However, his time in Parliament did not last long and he was defeated in the 1924 General Election. (6)

Arthur J. Cook went on to secure the official South Wales nomination and subsequently won the national ballot by 217,664 votes to 202,297. Fred Bramley, general secretary of the TUC, was appalled at Cook's election. He commented to his assistant, Walter Citrine: "Have you seen who has been elected secretary of the Miners' Federation? Cook, a raving, tearing Communist. Now the miners are in for a bad time." However, his victory was welcomed by Arthur Horner who argued that Cook represented “a time for new ideas - an agitator, a man with a sense of adventure”. (7)

Will Paynter was one of Cook's supporters but admitted that he "did not regard him as a good negotiator at pit level." However, "Cook had been a union leader at the colliery next down the valley to where I worked and we heard much of his exploits there as a fighter for wages and particularly for pit safety... He was, however, a master of his craft on the platform. I attended many of his meetings when he came to the Rhondda and he was undoubtedly a great orator, and had terrific support throughout the coalfields." (8)

Cook, a member of the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and The National Council of Action, an organisation formed to campaign against the possible British intervention in the Soviet Union. As a result MI5 kept a close watch on Cook, and his two friends, Noah Ablett and William H. Mainwaring: "A.J. Cook is prime mover in the Rhondda Council, and in conjunction with Davies and Ablett, will use the new movement as a preliminary to the establishment of the Soviet system of government." (9)

Cook, Ablett and Mainwaring were the authors of the pamphlet, The Miners' Next Step, that caused the government to be deeply concerned about the future direction of the MFGB. It stated: "That the organisation shall engage in political action, both local and national, on the basis of complete independence of, and hostility to all capitalist parties, with an avowed policy of wresting whatever advantage it can for the working class... Today the shareholders own and rule the coalfields. They own and rule them mainly through paid officials. The men who work in the mine are surely as competent to elect these, as shareholders who may never have seen a colliery. To have a vote in determining who shall be your fireman, manager, inspector, etc., is to have a vote in determining the conditions which shall rule your working life. On that vote will depend in a large measure your safety of life and limb, of your freedom from oppression by petty bosses, and would give you an intelligent interest in, and control over your conditions of work. To vote for a man to represent you in Parliament, to make rules for, and assist in appointing officials to rule you, is a different proposition altogether." (10)

Red Friday

On 30th June 1925 the mine-owners announced that they intended to reduce the miner's wages. Will Paynter later commented: "The coal owners gave notice of their intention to end the wage agreement then operating, bad though it was, and proposed further wage reductions, the abolition of the minimum wage principle, shorter hours and a reversion to district agreements from the then existing national agreements. This was, without question, a monstrous package attack, and was seen as a further attempt to lower the position not only of miners but of all industrial workers." (11)

On 23rd July, 1925, Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), moved a resolution at a conference of transport workers pledging full support to the miners and full co-operation with the General Council in carrying out any measures they might decide to take. A few days later the railway unions also pledged their support and set up a joint committee with the transport workers to prepare for the embargo on the movement of coal which the General Council had ordered in the event of a lock-out." (12) It has been claimed that the railwaymen believed "that a successful attack on the miners would be followed by another on them." (13)

In an attempt to avoid a General Strike, the prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, invited the leaders of the miners and the mine owners to Downing Street on 29th July. The miners kept firm on what became their slogan: "Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay". Herbert Smith, the president of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain, told Baldwin: "We have now to give". Baldwin insisted there would be no subsidy: "All the workers of this country have got to take reductions in wages to help put industry on its feet." (14)

The following day the General Council of the Trade Union Congress triggered a national embargo on coal movements. On 31st July, the government capitulated. It announced an inquiry into the scope and methods of reorganization of the industry, and Baldwin offered a subsidy that would meet the difference between the owners' and the miners' positions on pay until the new Commission reported. The subsidy would end on 1st May 1926. Until then, the lockout notices and the strike were suspended. This event became known as Red Friday because it was seen as a victory for working class solidarity. (15)

Herbert Smith pointed out that the real battle was to come: "We have no need to glorify about a victory. It is only an armistice, and it will depend largely how we stand between now and May 1st next year as an organisation in respect of unity as to what will be the ultimate results. All I can say is, that it is one of the finest things ever done by an organisation." (16)

Red Friday was a great success for Smith and Arthur J. Cook. However, Margaret Morris has argued that they had a difficult relationship: "Smith was temperamentally and politically the antithesis of Cook. Where Cook was emotional and voluble, Smith was dour and short of words. He was an old-style union leader, used to dominating the miners in Yorkshire... Relations between Smith and Cook were not always harmonious; neither of them really trusted the other's judgement, but each could respect that the other was dedicated to serving the miners. Neither of them was a very good negotiator: Cook was too excitable, and Smith perhaps a little too defensive in his tactics." (17)

Samuel Royal Commission

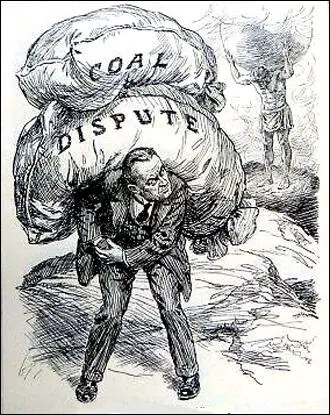

The Royal Commission was established under the chairmanship of Sir Herbert Samuel, to look into the problems of the Mining Industry. The commissioners took evidence from nearly eighty witnesses from both sides of the industry. They also received a great mass of written evidence, and visited twenty-five mines in various parts of Great Britain. The Samuel Commission published its report on 10th March 1926. Interest in it was so great that it sold over 100,000 copies. (18)

The Samuel Report was critical of the mine owners: "We cannot agree with the view presented to us by the mine owners that little can be done to improve the organization of the industry, and that the only practical course is to lengthen hours and to lower wages. In our view huge changes are necessary in other directions, and the large progress is possible". The report recognised that the industry needed to be reorganised but rejected the suggestion of nationalization. However, the report also recommended that the Government subsidy should be withdrawn and the miners' wages should be reduced. (19)

Herbert Smith rejected the Samuel Report and told a meeting with representatives of the colliery owners: "We are willing to do all we can to help this industry, but it is with this proviso, that when we have worked and given our best, we are going to demand a respectable day's wage for a respectable day's work; and that is not your intention." He added: "Not a penny off the pay, not a second on the day." (20)

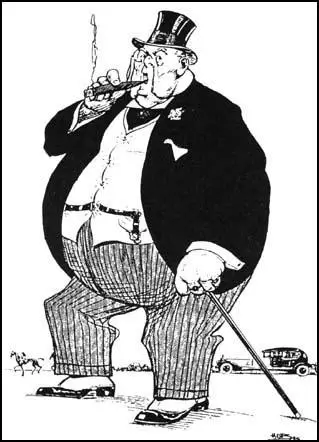

Trade Union Unity Magazine (1925)

The National Union of Mineworkers was put in a difficult position when Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), welcomed the Samuel Report as a "wonderful document". A. J. Cook, at the MFGB conference advised delegates not to reject the report outright, so as not to jeopardise the support of the TUC. He was aware of the need to appear reasonable, but he also reaffirmed his opposition to wage reductions: "I am of the opinion we have got the biggest fight of our lives in front of us, but we cannot fight alone." (21)

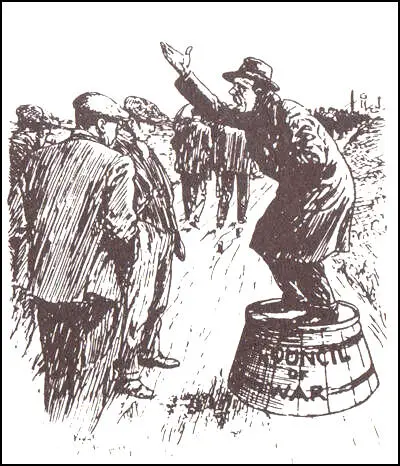

Cook toured the mining areas in an attempt to gain support for the proposed strike. It is claimed that he made as many as six speeches a day in an attempt to keep up the spirits of the miners. One former miner remembered: "Never were such vast crowds seen in the coalfields – perhaps never in Britain – as that which the Miners’ General Secretary, Mr. A.J. Cook addressed... He got, and held, the crowds. It was unusual to have a miners’ official going through the coalfields in this way... That Mr. Cook was a subject of great devotion was undeniable. He was a prophet among them. To this day men speak of those gatherings with awe." (22)

Arthur Horner later recalled: "We spoke together at meetings all over the country. We had audiences, mostly of miners, running into thousands. Usually I was put on first. I would make a good, logical speech, and the audience would listen quietly, but without any wild enthusiasm. Then Cook would take the platform. Often he was tired, hoarse and sometimes almost inarticulate. But he would electrify the meeting. They would applaud and nod their heads in agreement when he said the most obvious things. For a long time I was puzzled, and then one night I realised why it was. I was speaking to the meeting. Cook was speaking for the meeting. He was expressing the thoughts of his audience, I was trying to persuade them. He was the burning expression of their anger at the iniquities which they were suffering." (23)

Kingsley Martin, a journalist with the Manchester Guardian, was a supporter of the miners but was not convinced that Cook was the best person to negotiate an end to the dispute: "Cook made a most interesting study - worn-out, strung on wires, carried in the rush of the tidal wave, afraid of the struggle, afraid, above all, though, of betraying his cause and showing signs of weakness. He'll break down for certain, but I fear not in time. He's not big enough, and in an awful muddle about everything. Poor devil and poor England. A man more unable to conduct a negotiation I never saw. Many Trade Union leaders are letting the men down; he won't, but he'll lose. And Socialism in England will be right back again." (24)

David Kirkwood, took a different view of the general secretary of the MFGB: "The purpose of the General Strike was to obtain justice for the miners. The method was to hold the Government and the nation up to ransom. We hoped to prove that the nation could not get on without the workers. We believed that the people were behind us. We knew that the country had been stirred by our campaign on behalf of the miners. Arthur Cook, who talked from a platform like a Salvation Army preacher, had swept over the industrial districts like a hurricane. He was an agitator, pure and simple. He had no ideas about legislation or administration. He was a flame. Ramsay MacDonald called him a guttersnipe. That he certainly was not. He was utterly sincere, in deadly earnest, and burnt himself out in the agitation." (25)

The Daily Mail Strike

Stanley Baldwin and his ministers had several meetings with both sides in order to avoid the strike. Thomas Jones, the Deputy Secretary to the Cabinet, pointed out: "It is possible not to feel the contrast between the reception which Ministers give to a body of owners and a body of miners. Ministers are at ease at once with the former, they are friends jointly exploring a situation. There was hardly any indication of opposition or censure. It was rather a joint discussion of whether it was better to precipitate a strike or the unemployment which would result from continuing the present terms. The majority clearly wanted a strike." (26)

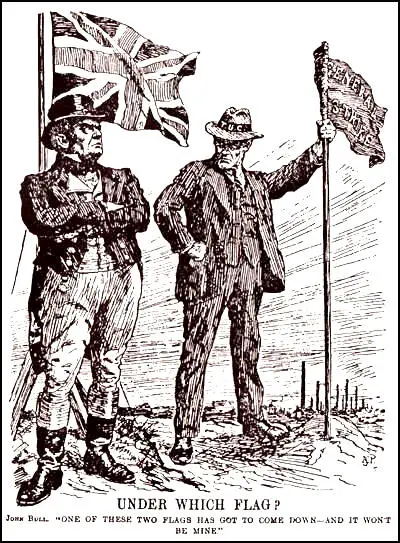

Considering themselves in a position of strength, the Mining Association now issued new terms of employment. These new procedures included an extension of the seven-hour working day, district wage-agreements, and a reduction in the wages of all miners. Depending on a variety of factors, the wages would be cut by between 10% and 25%. The mine-owners announced that if the miners did not accept their new terms of employment then from the first day of May they would be locked out of the pits. (27)

At the end of April 1926, the miners were locked out of the pits. A Conference of Trade Union Congress met on 1st May 1926, and afterwards announced that a General Strike "in defence of miners' wages and hours" was to begin two days later. The leaders of the Trade Union Council were unhappy about the proposed General Strike, and during the next two days frantic efforts were made to reach an agreement with the Conservative Government and the mine-owners. (28)

Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party refused to support the General Strike. MacDonald argued that strikes should not be used as a political weapon and that the best way to obtain social reform was through parliamentary elections. He was especially critical of A. J. Cook. He wrote in his diary: "It really looks tonight as though there was to be a General Strike to save Mr. Cook's face... The election of this fool as miners' secretary looks as though it would be the most calamitous thing that ever happened to the T.U. movement." (29)

The Trade Union Congress called the General Strike on the understanding that they would then take over the negotiations from the Miners' Federation. The main figure involved in an attempt to get an agreement was Jimmy Thomas. Talks went on until late on Sunday night, and according to Thomas, they were close to a successful deal when Stanley Baldwin broke off negotiations as a result of a dispute at the Daily Mail. (30)

What had happened was that Thomas Marlowe, the editor the newspaper, had produced a provocative leading article, headed "For King and Country", which denounced the trade union movement as disloyal and unpatriotic.The workers in the machine room, had asked for the article to be changed, when he refused they stopped working. Although, George Isaacs, the union shop steward, tried to persuade the men to return to work, Marlowe took the opportunity to phone Baldwin about the situation. (31)

The strike was unofficial and the TUC negotiators apologized for the printers' behaviour, but Baldwin refused to continue with the talks. "It is a direct challenge, and we cannot go on. I am grateful to you for all you have done, but these negotiations cannot continue. This is the end... The hotheads had succeeded in making it impossible for the more moderate people to proceed to try to reach an agreement." A letter was handed to the TUC negotiators that stated that the "gross interference with the freedom of the press" involved a "challenge to the constitutional rights and freedom of the nation". (32)

The General Strike

The General Strike began on 3rd May, 1926. Arthur Pugh, the chairman of the TUC, was put in charge of the strike. John Hodge believed that Pugh was ambivalent about the dispute. "I have never heard him say that he was in favour of it, but I have never heard him say that he was against it." (33) Hamilton Fyfe, the editor of the Daily Herald, was never convinced by him as a committed trade unionist and that given different circumstances "he would have made a fortune as a chartered accountant". (34)

Paul Davies, went further and claimed that Pugh was a reluctant participant in this conflict: "Pugh confessed that the SIC had no policy with which to conduct negotiations. The SIC reluctance to prepare was based on a complex mixture of moderation, defeatism and realism, but above all fear: fear of losing, fear of winning, fear of bloodshed, fear of unleashing forces that union leaders could not control." (35)

The Trade Union Congress adopted the following plan of action. To begin with they would bring out workers in the key industries - railwaymen, transport workers, dockers, printers, builders, iron and steel workers - a total of 3 million men (a fifth of the adult male population). Only later would other trade unionists, like the engineers and shipyard workers, be called out on strike. Ernest Bevin, the general secretary of the Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), was placed in charge of organising the strike. (36)

The TUC decided to publish its own newspaper, The British Worker, during the strike. Some trade unionists had doubts about the wisdom of not allowing the printing of newspapers. Workers on the Manchester Guardian sent a plea to the TUC asking that all "sane" newspapers be allowed to be printed. However, the TUC thought it would be impossible to discriminate along such lines. Permission to publish was sought by George Lansbury for Lansbury's Labour Weekly and H. N. Brailsford for the New Leader. The TUC owned Daily Herald also applied for permission to publish. Although all these papers could be relied upon to support the trade union case, permission was refused. (37)

The government reacted by publishing The British Gazette. Baldwin gave permission to Winston Churchill to take control of this venture and his first act was commandeer the offices and presses of The Morning Post, a right-wing newspaper. The company's workers refused to cooperate and non-union staff had to be employed. Baldwin told a friend that he gave Churchill the job because "it will keep him busy, stop him doing worse things". He added he feared that Churchill would turn his supporters "into an army of Bolsheviks". (38)

Churchill, along with Frederick Smith, Lord Birkenhead, were members of the government who saw the strike as "an enemy to be destroyed." Lord Beaverbrook described him as being full of the "old Gallipoli spirit" and in "one of his fits of vainglory and excessive excitement". Thomas Jones attempted to develop a plan that would bring the dispute to an end. Churchill was furious and said that the government should reject a negotiated settlement. Jones described Churchill as a "cataract of boiling eloquence" and told him that "we are at war" and the battle should continue until the government won. (39)

John C. Davidson, the chairman of the Conservative Party, commented that Churchill was "the sort of man whom, if I wanted a mountain to be moved, I should send for at one. I think, however, that I should not consult him after he had moved the mountain if I wanted to know where to put it." (40) Neville Chamberlain found Churchill's approach unacceptable and wrote in his diary that "some of us are going to make a concerted attack on Winston... he simply revels in this affair, which he will continually treat and talk of as if it were 1914." (41)

Davidson, who had been put in overall charge of the government's media campaign, grew increasingly frustrated by Churchill's willingness to distort or suppress any item which might be vaguely favourable to "the enemy". Davidson argued that Churchill's behaviour became so extreme that he lost the support of the previously loyal Lord Birkenhead: "Winston, who had it firmly in his mind that anybody who was out of work was a Bolshevik; he was most extraordinary and never have I listened to such poppycock and rot." (42)

Churchill called for the government to seize union funds. This was rejected and Churchill was condemned for his "wild ways". John Charmley has argued that "Churchill had a sentimentalist upper-class view of grateful workers co-operating with their betters for the good of the nation; he neither understood, nor realised that he did not understand, the Labour movement. To have written about the TUC leaders as though they were potential Lenins and Trotskys said more about the state of Churchill's imagination than it did about his judgment." (43)

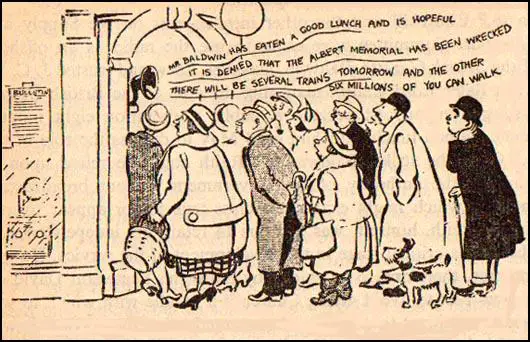

The government relied on volunteers to do the work of the strikers. Cass Canfield, worked in publishing until the strike began. "The British General Strike, which occurred in 1926, completely tied up the nation until the white-collar class went to work and restored some of the services. I remember watching gentlemen with Eton ties acting as porters in Waterloo Station; other volunteers drove railroad engines and ran buses. I was assigned to delivering newspapers and would report daily, before dawn, at the Horse Guards Parade in London. As time passed, the situation worsened; barbed wire appeared in Hyde Park, and big guns. Winston Churchill went down to the docks in an attempt to quell the rioting. For a couple of days there were no newspapers, and that was hardest of all to bear for no one knew what was going to happen next and everyone feared the outbreak of widespread violence. Finally, a single-sheet government handout appeared - the British Gazette - and people breathed easier, but settlement of the issues dividing labor and the government appeared to be insoluble." (44)

However, most members of the Labour Party supported the strikers. This included Margaret Cole, who worked for the Fabian Research Department, pointed out: "Some members of the Labour Club formed a University Strike Committee, which set itself three main jobs; to act as liaison between Oxford and Eccleston Square, then the headquarters of the TUC and the Labour Party, to get out strike bulletins and propaganda leaflets for the local committees, and to spread them and knowledge of the issues through the University and the nearby villages." (45)

The Media and the General Strike

In his book on the the General Strike, the historian Christopher Farman, studied the way the media dealt with this important industrial dispute. John C. Davidson, the Chairman of the Conservative Party, was given responsibility for the way the media should report the strike. "As soon as it became evident that newspaper production would be affected by the strike, Davidson arranged to bring the British Broadcasting Company under his effective control... no news was broadcast during the crisis until it had first been personality vetted by Davidson... Each of the five daily news bulletins plus a daily 'appreciation of the situation', which took the place of newspaper editorials, were drafted by Gladstone Murray in conjunction with Munro and then submitted to Davidson for his approval before being transmitted from the BBC's London station at Savoy Hill." (46)

As part of the government propaganda campaign, the BBC reported that public transport was functioning again and after the first week of the strike it announced that most railmen had returned to work. This was in fact untrue as 97% of National Union of Railwaymen members remained on strike. It was true that volunteers were emerging from training and that more trains were in service. However, there was a sharp increase in accidents and several passengers were killed during the strike. Unskilled volunteers were also accused of causing thousands of pounds' worth of damage. (47)

Several politicians representing the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party, appeared on BBC radio and made vicious attacks on the trade union movement. William Graham, the Labour Party MP for Edinburgh Central, wrote to John Reith, the BBC's managing director, suggesting that he should allow "a representative Labour or Trade Union leader to state the case for the miners and other workers in this crisis". (48)

Ramsay MacDonald, the leader of the Labour Party, also contacted Reith and asked for permission to broadcast his views. Reith recorded in his diary: "He (MacDonald) said he was anxious to give a talk. He sent a manuscript along... with a friendly note offering to make any alterations which I wanted... I sent it at once to Davidson for him to ask the Prime Minister, strongly recommending that he should allow it to be done." The idea was rejected and Reith argued: "I do not think that they treat me altogether fairly. They will not say we are to a certain extent controlled and they make me take the onus of turning people down. They are quite against MacDonald broadcasting, but I am certain it would have done no harm to the Government. Of course it puts me in a very awkward and unfair position. I imagine it comes chiefly from the PM's difficulties with the Winston lot." (49)

When he heard the news, MacDonald, wrote Reith an angry letter, calling "for an opportunity for the fair-minded and reasonable public to hear Labour's point of view". Anne Perkins, the author of A Very British Strike: 3 May-12 May 1926 (2007) has argued that if the government had accepted the proposal and people had "heard an Opposition voice would certainly have done something to restore the faith of millions of working-class people who had lost confidence in the BBC's potential to be a national institution and a reliable and trustworthy source of news." (50)

At the same time Stanley Baldwin was allowed to make several broadcasts on the BBC. Baldwin "had recognized the importance of the new medium from its inception... now, with an expert blend of friendliness and firmness, he repeated that the strike had first to be called off before negotiations could resume, but repudiated the suggestion that the Government was fighting to lower the standard of living of the miners or of any other section of the workers". (51)

In one broadcast Baldwin argued: "A solution is within the grasp of the nation the instant that the trade union leaders are willing to abandon the General Strike. I am a man of peace. I am longing and working for peace, but I will not surrender the safety and security of the British Constitution. You placed me in power eighteen months ago by the largest majority accorded to any party for many years. Have I done anything to forfeit that confidence? Cannot you trust me to ensure a square deal, to secure even justice between man and man?" (52)

By 12th May, 1926, most of the daily newspapers had resumed publication. The Daily Express reported that the "strike had a broken back" and it would be all over by the end of the week. (53) Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere, was extremely hostile to the strike and all his newspapers reflected this view. The Daily Mirror stated that the "workers have been led to take part in this attempt to stab the nation in the back by a subtle appeal to the motives of idealism in them." (54) The Daily Mail claimed that the strike was one of "the worst forms of human tyranny". (55)

Negotiations with the TUC

Walter Citrine, the general secretary of the Trade Union Congress (TUC), was desperate to bring an end to the General Strike. He argued that it was important to reopen negotiations with the government. His view was "the logical thing is to make the best conditions while our members are solid". Baldwin refused to talk to the TUC while the General Strike persisted. Citrine therefore contacted Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), who shared this view of the strike, and asked him to arrange a meeting with Herbert Samuel, the Chairman of the Royal Commission on the Coal Industry. (56)

Without telling the miners, the TUC negotiating committee met Samuel on 7th May and they worked out a set of proposals to end the General Strike. These included: (i) a National Wages Board with an independent chairman; (ii) a minimum wage for all colliery workers; (iii) workers displaced by pit closures to be given alternative employment; (iv) the wages subsidy to be renewed while negotiations continued. However, Samuel warned that subsequent negotiations would probably mean a reduction in wages. These terms were accepted by the TUC negotiating committee, but were rejected by the executive of the Miners' Federation. (57)

Herbert Smith was furious with the TUC for going behind the miners back. One of those involved in the negotiations, John Bromley of the NUR, commented: "By God, we are all in this now and I want to say to the miners, in a brotherly comradely spirit... this is not a miners' fight now. I am willing to fight right along with them and suffer as a consequence, but I am not going to be strangled by my friends." Smith replied: "I am going to speak as straight as Bromley. If he wants to get out of this fight, well I am not stopping him." (58)

Walter Citrine wrote in his diary: "Miner after miner got up and, speaking with intensity of feeling, affirmed that the miners could not go back to work on a reduction in wages. Was all this sacrifice to be in vain?" Citrine quoted Cook as saying: "Gentleman, I know the sacrifice you have made. You do not want to bring the miners down. Gentlemen, don't do it. You want your recommendations to be a common policy with us, but that is a hard thing to do." (59)

Herbert Smith asked Arthur Pugh if the decision was "the unanimous decision of your Committee?" Pugh replied that it was the view that the General Strike should come to an end. Smith pleaded for further negotiations. However, Pugh was insistent: "That is it. That is the final decision, and that is what you have to consider as far as you are concerned, and accept it." (60)

On the 11th May, at a meeting of the Trade Union Congress General Committee, it was decided to accept the terms proposed by Herbert Samuel and to call off the General Strike. The following day, the TUC General Council visited 10 Downing Street and attempted to persuade the Government to support the Samuel proposals and to offer a guarantee that there would be no victimization of strikers.

Baldwin refused but did say if the miners returned to work on the current conditions he would provide a subsidy for six weeks and then there would be the pay cuts that the Mine Owners Association wanted to impose. He did say that he would legislate for the amalgamation of pits, introduce a welfare levy on profits and introduce a national wages board. The TUC negotiators agreed to this deal. As Lord Birkenhead, a member of the Government was to write later, the TUC's surrender was "so humiliating that some instinctive breeding made one unwilling even to look at them." (61)

Baldwin already knew that the Mine Owners Association would not agree to the proposed legislation. They had already told Baldwin that he must not meddle in the coal industry. It would be "impossible to continue the conduct of the industry under private enterprise unless it is accorded the same freedom from political interference that is enjoyed by other industries." (62)

To many trade unionists, Walter Citrine had betrayed the miners. A major factor in this was money. Strike pay was haemorrhaging union funds. Information had been leaked to the TUC leaders that there were cabinet plans originating with Winston Churchill to introduce two potentially devastating pieces of legislation. "The first would stop all trade union funds immediately. The second would outlaw sympathy strikes. These proposals would... make it impossible for the trade unions' own legally held and legally raised funds to be used for strike pay, a powerful weapon to drive trade unionists back to work." (63)

Seven Month Lockout

Arthur Pugh, the President of the Trade Union Congress, and Jimmy Thomas, the general secretary of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR), informed the Miners' Federation of Great Britain leaders, that if the General Strike was terminated the government would instruct the owners to withdraw their notices, allowing the miners to return to work on the "status quo" while the wage reductions and reorganisation machinery were negotiated. A. J. Cook asked what guarantees the TUC had that the government would introduce the promised legislation, Thomas replied: "You may not trust my word, but will not accept the word of a British gentleman who has been Governor of Palestine". (64)

Jennie Lee, was a student at Edinburgh University when her father, a miner in Lochgelly in Scotland. During the lock-out she returned to help her family. "Until the June examinations were over I was chained to my books, but I worked with a darkness around me. What was happening in the coalfield? How were they managing? Once I was free to go home to Lochgelly my spirits rose. When you are in the thick of a fight there is a certain exhilaration that keeps you going." (65)

When the General Strike was terminated, the miners were left to fight alone. Cook appealed to the public to support them in the struggle against the Mine Owners Association: "We still continue, believing that the whole rank and file will help us all they can. We appeal for financial help wherever possible, and that comrades will still refuse to handle coal so that we may yet secure victory for the miners' wives and children who will live to thank the rank and file of the unions of Great Britain." (66)

On 21st June 1926, the British Government introduced a Bill into the House of Commons that suspended the miners' Seven Hours Act for five years - thus permitting a return to an 8 hour day for miners. In July the mine-owners announced new terms of employment for miners based on the 8 hour day. As Anne Perkins has pointed out this move "destroyed any notion of an impartial government". (67)

A. J. Cook toured the coalfields making passionate speeches in order to keep the strike going: "I put my faith to the women of these coalfields. I cannot pay them too high a tribute. They are canvassing from door to door in the villages where some of the men had signed on. The police take the blacklegs to the pits, but the women bring them home. The women shame these men out of scabbing. The women of Notts and Derby have broken the coal owners. Every worker owes them a debt of fraternal gratitude." (68)

Hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of August, 80,000 miners were back, an estimated ten per cent of the workforce. 60,000 of those men were in two areas, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. "Cook set up a special headquarters there and rushed from meeting to meeting. He was like a beaver desperately trying to dam the flood. When he spoke, in, say, Hucknall, thousands of miners who had gone back to work would openly pledge to rejoin the strike. They would do so, perhaps for two or three days, and then, bowed down by shame and hunger, would drift back to work." (69)

Herbert Smith and Arthur Cook had a meeting with government representatives on 26th August, 1926. By this stage Cook was willing to do a deal with the government than Smith. Cook asked Winston Churchill: "Do you agree that an honourably negotiated settlement is far better than a termination of struggle by victory or defeat by one side? Is there no hope that now even at this stage the government could get the two sides together so that we could negotiate a national agreement and see first whether there are not some points of agreement rather than getting right up against our disagreements." (70) According to Beatrice Webb "if it were not for the mule-like obstinacy of Herbert Smith, A. J. Cook would settle on any terms." (71)

This meeting revealed the differences between Smith and Cook. "After a wary start the two seem to have developed a mutual respect during their many hours of shared stress. By the middle of the lock-out, however, they seem to have drifted on to different. wavelengths. Undoubtedly Cook felt Smith's obstinacy to be impractical and damaging. Smith, however, as MFGB President, was the Federation's chief spokesman, and Cook could not officially or openly dissociate himself from Smith's position. The MFGB special conference had granted the officials unfettered negotiating power, but Smith seems to have grown more stubborn as the miners' bargaining position worsened. One may admire his spirit, but not his wisdom. It is likely that by this time Smith reflected a minority view within the Federation Executive, but as President his position was unchallengeable, and there was no public dissent at his inflexibility. Cook, meanwhile, had embraced a conciliatory, face-saving position: he was only too aware of the drift back to work in some areas; he saw the deteriorating condition of many miners and their families." (72)

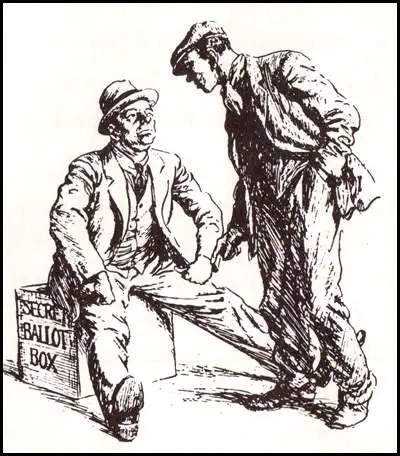

Bernard Partridge, Secret Ballot (13th October 1926)

In October 1926 hardship forced men to begin to drift back to the mines. By the end of November most miners had reported back to work. Will Paynter remained loyal to the strike although he knew they had no chance of winning. "The miners' lock-out dragged on through the months of 1926 and really was petering-out when the decision came to end it. We had fought on alone but in the end we had to accept defeat spelt out in further wage-cuts." (73)

when you can starve for mine" (13th October 1926)

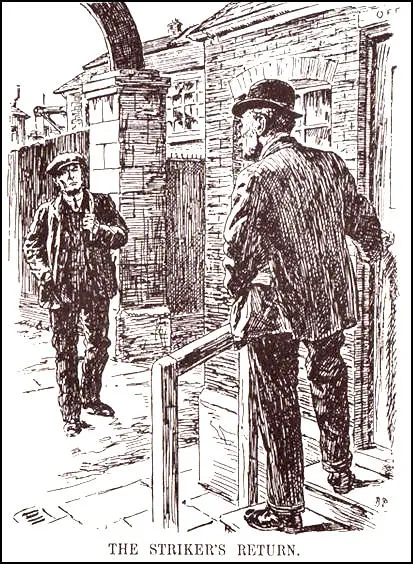

As one historian pointed out: "Many miners found they had no jobs to return to as many coal-owners used the eight-hour day to reduce their labour force while maintaining productions levels. Victimisation was practised widely. Militants were often purged from payrolls. Blacklists were drawn up and circulated among employers; many energetic trade unionists never worked in a pit again after 1926. Following months of existence on meague lockout payments and charity, many miners' families were sucked by unemployment, short-term working, debts and low wages into abject poverty." (74)

The Aftermath

At the end of the strike some people were highly critical of the way the government had used its control of the media to spread false news. This included an attack on the The British Gazette. One journalist wrote: "One of the worst outrages which the country had to endure - and to pay for - in the course of the strike, was the publication of the British Gazette. This organ, throughout the seven days of its existence, was a disgrace alike to the British Government and to British journalism." (75)

The vast majority of newspapers supported the government during the dispute. This was especially true of the newspapers owned by Lord Rothermere. The Daily Mail suggested that "the country has come through deep waters and it has come through in triumph, setting such an example to the world as has not been seen since the immortal hours of the War. It has fought and defeated the worst forms of human tyranny. This is a moment when we can lift up our head and our hearts." (76) The Daily Mirror compared the strikers to a foreign enemy: "The unconquerable spirit of our people has been aroused again in self-defence - as it was against the foreign foe in 1914." (77) The Times took a similar line arguing that the General Strike was "a fundamental struggle between right and wrong... victory was won... by the splendid courage and self-sacrifice of the nation itself." (78)

The Manchester Guardian disagreed and condemned the right-wing press for comparing strikers to a foreign enemy and urging the government to "teach the workmen the lesson they deserve". The newspaper reminded those editors like Thomas Marlowe, that many of these men had a few years earlier been praised for bravery during the First World War. It added the "comradeship" developed during the war "was a big factor in the unparalleled pacific character of this great conflict". (79)

John Reith, the BBC's managing director, was concerned about the way the government had controlled what it was able to broadcast. In a confidential letter sent to senior BBC staff, Reith wrote. "The attitude of the BBC during the crisis caused pain and indignation to many subscribers. I travelled by car over two thousand miles during the strike and addressed very many meetings. Everywhere the complaints were bitter that a national service subscribed to by every class should have given only one side during the dispute. Personally, I feel like asking the Postmaster-General for my licence fee back." (80)

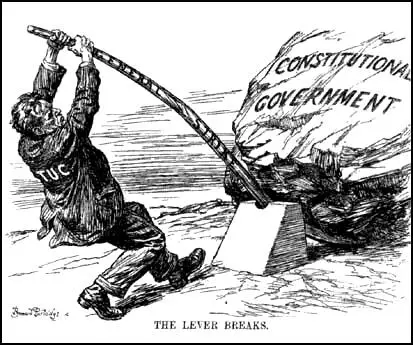

In 1927 the British Government passed the Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act. This act made all sympathetic strikes illegal, ensured the trade union members had to voluntarily 'contract in' to pay the political levy to the Labour Party, forbade Civil Service unions to affiliate to the TUC, and made mass picketing illegal. As A. J. P. Taylor has pointed out: "The attack on Labour party finance came ill from the Conservatives who depended on secret donations from rich men." (81)

The legislation defined all sympathetic strikes as illegal, confining the right to strike to "the trade or industry in which the strikers are engaged". The funds of any union engaging in an illegal strike was liable in respect of civil damages. It also limited the right to picket, in terms so vague that almost any form of picketing might be liable to prosecution. As Julian Symons has pointed out: "More than any other single measure, the Trade Disputes Act caused hatred of Baldwin and his Government among organized trade unionists." (82)

One of the results of this legislation was that trade union membership fell below the 5,000,000 mark for the first time since 1926. However, despite its victory over the trade union movement, the public turned against the Conservative Party. Over the next three years the Labour Party won all the thirteen by-elections that took place. In the 1929 General Election Labour won 287 seats and its leader, Ramsay MacDonald, formed the next government.

Primary Sources

(1) Kingsley Martin first met Winston Churchill while teaching at the London School of Economics. Martin wrote about Churchill and the General Strike in his book, Father Figures (1966)

The General Strike of 1926 was an unmitigated disaster. Not merely for Labour but for England. Churchill and other militants in the cabinet were eager for a strike, knowing that they had built a national organisation in the six months' grace won by the subsidy to the mining industry. Churchill himself told me this on the first occasion I met him in person. I asked Winston what he thought of the Samuel Coal Commission. When Winston said that the subsidy had been granted to enable the Government to smash the unions, unless the miners had given way in the meantime, my picture of Winston was confirmed.

(2) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934)

During the nine days of the strike I remained silent. From one point of view I was not sorry that this experiment had been tried. The Trade Unions needed a lesson of the futility and foolishness of such a trial of strength. A general strike could in no circumstances be successful. A general strike is an attempt to hold up the community, and against such an attempt the community will mobilize all its resources. There is no country in the world which has proportionally such a large middle-class population as Great Britain. They with the help of governmental organisation, with a million motor-cars at their service, could defeat any strike on a large scale which threatened the vital services.

(3) Ramsay MacDonald, diary entry (2nd May, 1926)

Wonderfully serious and spiritually united Conference sat for two days in Memorial Hall... Miners' plea that they were defending general standard of life of workers has united T.U.'s with them, and as the real problem of breakdown of mining industry has been dealt with in propaganda minds and by stunt phrases, we are up against the hard face of impossibility as miners cannot budge from "not a shilling and not a minute" formula. The Government has woefully mismanaged the whole business... But the T.Us have been equally blameworthy: 1. Miners' impossible formula. 2. Allowing themselves to fall into general strike psychology. General Strike declared and at the meeting of T.U. General Council yesterday evident no forethought. No definite idea of what they are to consider as satisfactory to enable them to finish and go back to work. Position wonderfully like 1914. Strike cannot settle purely economic problem of bankruptcy of industry. Were it to be "won" industry remains bankrupt. Employers in the various trades may not remain passive, but may raise own trade matters. Will strike continue to help section after section? At T.U. General Council Meetings men like Bevin, Thomas etc. saw this and were plainly trying to avoid it. Question raised: How far could they pledge miners to accept a readjustment of wages. But alas, miners' executive gone home and Cook who alone is in town declined responsibility of answering for them. Rightly! It really looks tonight as though there was to be a General Strike to save Mr. Cook's face. Important man! The election of this fool as miners' secretary looks as though it would be the most calamitous thing that ever happened to the T.U. movement.

(4) Kingsley Martin , diary entry (26th April, 1926)

Cook made a most interesting study - worn-out, strung on wires, carried in the rush of the tidal wave, afraid of the struggle, afraid, above all, though, of betraying his cause and showing signs of weakness. He'll break down for certain, but I fear not in time. He's not big enough, and in an awful muddle about everything. Poor devil and poor England. A man more unable to conduct a negotiation I never saw. Many Trade Union leaders are letting the men down; he won't, but he'll lose. And Socialism in England will be right back again.

(5) Jennie Lee, was a student at Edinburgh University when her father, a miner, was involved in the General Strike. She wrote about it in her book, My Life With Nye (1980).

Although the General Strike lasted only ten days the miners held out from April until December. Until the June examinations were over I was chained to my books, but I worked with a darkness around me. What was happening in the coalfield? How were they managing? Once I was free to go home to Lochgelly my spirits rose. When you are in the thick of a fight there is a certain exhilaration that keeps you going.

Stanley Baldwin promised that there would be no victimization when the miners went back to work. That was one more piece of deliberate deception. My father was not reinstated - from four months he trudged from pit to pit, turned away everywhere. Uncle Michael was also victimized, and so sadly he came to the decision that the only thing to do was to go off to America.

(6) Margaret Cole, Growing up into Revolution (1949)

Some members of the Labour Club formed a University Strike Committee, which set itself three main jobs; to act as liaison between Oxford and Eccleston Square, then the headquarters of the TUC and the Labour Party, to get out strike bulletins and propaganda leaflets for the local committees, and to spread them and knowledge of the issues through the University and the nearby villages. My job was to be liaison officer, and half-a-dozen times during those nine days I was driven up to London by Hugh Gaitskill or John Dugdale to Eccleston Square, to collect supplies of the British Worker, any other news or instructions that were going, and while we were there to have a look at the centre of things; and to transport anyone who happened to require transport about the city.

The Government had made up its mind that "direct action" must be scotched once and for all, and, that being so, the Unions had no choice between surrendering and going on to civil war and revolution, which was the last thing they had envisaged or desired. They surrendered, ingloriously, but with the ranks unbroken; and though the immediate outcome was, naturally, a falling-off of membership, and a good deal of angry recrimination, the absence of any real revanche, any sacking of the leaders who had patently failed to lead, showed that the movement, when it had time to think things over, realised that it had in effect made a challenge to the basis of British society which it was not prepared to see through and that, therefore, post-mortems on who was to blame was unprofitable.

The industrial workers forgave their leaders. But they did not so easily forgive their enemies, particularly when the Government, to punish them for their insubordination, rushed through the 1927 Trade Union Act. This was a piece of political folly; it did not (because it could not) prevent strikes; what it did was to make it more easy to victimize local strike-leaders and also to put obstacles in the way of the Unions contributing to the funds of their own political Party.

(7) Henry Hamilton Fyfe, My Seven Selves (1935)

It is still frequently asserted, and perhaps by many believed, that this abortive attempt by Trade Unionists to assist their comrades, the miners, was an attack on the Constitution, a blow aimed at the State, a revolutionary act. It is natural enough for opponents of Labour, whether political or industrial, to misrepresent the General Strike in that way, but a number of writers of books have erred through ignorance.

No one who was acquainted with the Trade Union leaders at that period, no one who watched from inside the day-to-day development of the affair, can think of this assertion with anything but amusement. There was not a single member of the General Council of the Trade Union Congress who would not have shrunk with horror from the idea of overturning the established order - if it had occurred to him. I am certain there was no one to whom it did occur. They decided on the strike in desperation. They had promised support to the miners, and they did not know what else to do.

(8) David Kirkwood, My Life of Revolt (1935)

The purpose of the General Strike was to obtain justice for the miners. The method was to hold the Government and the nation up to ransom. We hoped to prove that the nation could not get on without the workers. We believed that the people were behind us. We knew that the country had been stirred by our campaign on behalf of the miners.

Mr Arthur Cook, who talked from a platform like a Salvation Army preacher, had swept over the industrial districts like a hurricane. He was an agitator, pure and simple. He had no ideas about legislation or administration. He was a flame. Ramsay MacDonald called him a guttersnipe. That he certainly was not. He was utterly sincere, in deadly earnest, and burnt himself out in the agitation.

I was heartily in favour of the General Strike. I believed we should see such an uprising of the people that the Government would be forced to grant our demands.

(9) Helen Crawfurd, The Woman Worker (August 1926)

To the women in the coalfields, whether wife, sister or mother of the miner miner, the present situation gives food for thought.

Along with the menfolk; she has faced hunger, uncertainty and the knowledge of debts mounting up and of health and strength going down. Her own hunger has been bad enough, but that of her children has been infinitely more terrible.

Sunshine and the company of her fellows in meeting or demonstration;has kept alive in her spark of hope. Financial, help from workers in all lands, especially from Soviet Russia has proved to her the fellow feeling of the international working class. Red Friday of last year had encouraged her to hope, that the bitter lessons learned by the 1921 betrayal (Black Friday), and the subsequent reductions of all workers’ wages during 1922 (£,600,000,000) had been effective.

Whatever the leaders of the General Council may say, the fact remains that the magnificent solidarity shown by the organised workers during the nine days of the General Strike, was in support of the miners’ slogan, “Not a penny off the Pay. Not a Minute on the day.” They had learned that if the miners’ conditions were worsened theirs would follow as in 1922. The magnificent solidarity shown during those nine days gave promise of the struggle being, short and decisive. The calling off of the strike and the subsequent weeks of slow torture and suffering of the miners, their wives and children, are something that will go down in history as an infinitely greater betrayal than that of 1921. Not only was it a betrayal of the miners, but it was a gross betrayal of the whole Trade Union Movement. If Thomas and the other members of the General Council thought the Strike was wrong why did they not denounce it? Why did they not resign before leading their men into it? And why, having led them into it and having definitely promised in their directions sent out that:

“The General Council further direct that Executives of the Unions concerned shall definitely declare that in the event of any action being taken and trade union agreements being placed in jeopardy, it be definitely agreed that there will be no general resumpution of work until those agreements are fully recognised.” (Memorandum sent out by T.U.C., 30th April, 1926; signed A. Pugh, Chairman, Walter Citrine, Secretary.)

Why, having made this promise, did they allow their members to be humiliated by signing in their name the most grovelling and humiliating terms of peace, while still in a position to gain honourable terms.

The General Council of the Trades Union Congress, in order to save their miserable faces and to whitewash themselves, must needs find a scapegoat and put their sins upon it and send it out into the wilderness - and they foolishly imagine that in their recent attempt to vilify the leaders of the miners, they have as easily hoodwinked the British workers as the children of Israel fondly imagined they could hoodwink their God. Well, it won’t just work, and the day of reckoning is approaching!!! The rank and file of the workers did not betray the miners, neither in the General Strike, nor even in the present situation which calls for an embargo in handling of all coal. Again, it is the weak and vacillating, leadership which is proving itself Capitalism’s most valuable ally. Baldwin must go, and so must his allies.

If Cook could be made to hear the voice of the whole working class, who are solidly behind him and the miners, they would never hesitate. Only the operation of the embargo without waiting for a decision by the men who betrayed the General Strike will assure them of this support.

The leaders, like Clynes, MacDonald Thomas and Cramp, declare that the workers are not ready to give active support. This is not true. The workers are always in front of their Right-wing “leaders,” and the Dockers’ Strike in Plymouth and Boulogne, the Railwaymen’s Delegate Conference in South Wales, the resolution of the Manchester Railway Shopmen, have all shown that the mass of workers are profoundly dissatisfied with the unjustifiable calling off the Strike before justice was secured for the miners, and the other workers safeguarded against victimisation.

The workers realise that if the miners go back to work with lower wages and longer hours that will be only the first of a series of defeats inflicted on the whole working class. Next it will be the turn of the railwaymen, then the transport workers and dockers. Only a victory for the miners will protect wages. Only the embargo will enforce a victory for the miners.

And now the Bishops have appeared on the scene. Have they come to tell their fellow Bishops, who live largely on mining royalties to disgorge their ill-gotten gains? (The Bishop of Durham has £7,000 a year.) No, again it is the Baldwin slogan set to celestial music. “ The wages of all workers must come down” and again the miners must be the first victims. Arbitration and a promise to submit in advance to the findings of this arbitration court, is more dangerous ground than the workers have hitherto been called to traverse.

We Communists believe that capitalism can only continue to exist at the expense of the increasing misery of the working class. We also believe that only by loyalty and solidarity and organisation, can the workers triumph. The Bishops “whether consciously or unconsciously” to give them the benefit of the doubt, are simply another move in the capitalist game.

To you, women, the dark night seems long. But the organised might of the working class, under the courageous leadership of the Communist Party alone can bring the dawn and freedom to the struggling working class internationally.

(10) Henry Hamilton Fyfe helped to edit the Daily Worker during the General Strike.

The Government organ was called the British Gazette. We named ours the British Worker. Churchill ran theirs in his flamboyant style. We kept ours moderate in statement and strictly matter-of-fact. The Times paid us this tribute: "Although frankly propagandist, the British Worker has on the whole been a straightforward and moderate influence."

The TUC appointed censors to sit in the office and read the proofs. But these were easily managed. Our real difficulty was lack of paper. We were printing numbers far in excess of the Herald circulation. We went up actually to seven hundred and fifty thousand copies. Even then a cry arose from many parts of the country: "Give us more: we can sell them."

In the hope of shutting us down, or at any rate lowering our circulation. Baldwin meanly interfered with our paper supplies. I learned during the strike and the events which led to it how deceptive was the appearance of good humour and honest frankness which this adroit politician maintained.

(11) Herbert Morrison, An Autobiography (1960)

The story of the strike has been told so often that it is unnecessary to repeat it here. Suffice it to say that in Hackney, as in every working-class area, there was great sympathy for the miners, who had been treated abominably, and there was a universal and reasonably justified feeling that the mineowners were a wicked lot. But there was also some feeling among the basically law-abiding and sensible working people of our country that political power could not, and should not, be won by industrial action. However, the strike call met with a loyal response.

(12) Walter Citrine, Men and Work (1964)

I do not regard for General Strike as a failure. It is true that it was ill-prepared and that it was called off without any consultation with those who took part in it. The fact is that the theory of the General Strike had never been thought out. The machinery of the trade unions was not adapted for it. Their rules had to be broken for the executives to give power to the General Council to declare the strike. However illogical it may seem for me to say so, it was never aimed against the state as a challenge to the Constitution. It was a protest against the degradation of the standards of life of millions of good trade unionists. It was a sympathetic strike on a national scale. It was full of imperfections in concept and method. No General Strike could ever function without adequate local organization, and the trade unions were not ready to devolve such necessary powers on the only local agents which the T.U.C. has, the Trades Councils.

(13) Cass Canfield, Up and Down and Around (1971)

The British General Strike, which occurred in 1926, completely tied up the nation until the white-collar class went to work and restored some of the services. I remember watching gentlemen with Eton ties acting as porters in Waterloo Station; other volunteers drove railroad engines and ran buses. I was assigned to delivering newspapers and would report daily, before dawn, at the Horse Guards Parade in London. As time passed, the situation worsened; barbed wire appeared in Hyde Park, and big guns. Winston Churchill went down to the docks in an attempt to quell the rioting. For a couple of days there were no newspapers, and that was hardest of all to bear for no one knew what was going to happen next and everyone feared the outbreak of widespread violence. Finally, a single-sheet government handout appeared - the British Gazette - and people breathed easier, but settlement of the issues dividing labor and the government appeared to be insoluble. The strike dragged on for a fortnight, with apparently no end in sight. Then, one day, the skies cleared; a compromise was reached and the workers returned to their jobs. It was remarkable that no bad feeling persisted between the opposing camps in view of the fact that the Country had faced a possible revolution.

Student Activities

The Outbreak of the General Strike (Answer Commentary)

The 1926 General Strike and the Defeat of the Miners (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)