Collectivisation of Agriculture

In 1926 Joseph Stalin formed an alliance with Nikolay Bukharin, Mikhail Tomsky and Alexei Rykov, on the right of the party, who wanted an expansion of the New Economic Policy that had been introduced several years earlier. Farmers were allowed to sell food on the open market and were allowed to employ people to work for them. Those farmers who expanded the size of their farms became known as kulaks. Bukharin believed the NEP offered a framework for the country's more peaceful and evolutionary "transition to socialism" and disregarded traditional party hostility to kulaks. (1)

This move upset those on the left of the party such as Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev. According to Robert Service, the author of Stalin: A Biography (2004): "Stalin and Bukharin rejected Trotsky and the Left Opposition as doctrinaires who by their actions would bring the USSR to perdition... Zinoviev and Kamenev felt uncomfortable with so drastic a turn towards the market economy... They disliked Stalin's movement to a doctrine that socialism could be built in a single country - and they simmered with resentment at the unceasing accumulation of power by Stalin." (2)

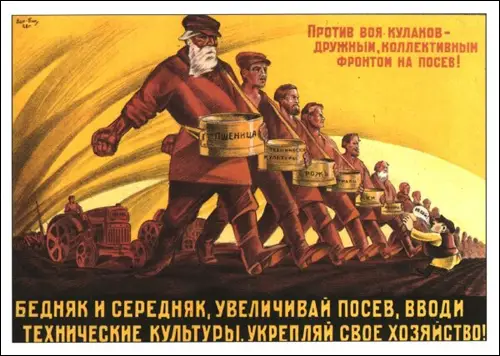

Kamenev and Zinoviev denounced the pro-Kulak policy, arguing that the stronger the big farmers grew the easier it would be for them to withhold food from the urban population and to obtain more and more concessions from the government. Eventually, they might be in a position to overthrow communism and the restoration of capitalism. Before the Russian Revolution there had been 16 million farms in the country. It now had 25 million, some of which were very large and owned by kulaks. They argued that the government, in order to undermine the power of the kulaks, should create large collective farms. (3)

Bukharin and the Kulaks

Stalin tried to give the impression he was an advocate of the middle-course. In reality, he was supporting those on the right. In October, 1925, the leaders of the left in the Communist Party submitted to the Central Committee a memorandum in which they asked for a free debate on all controversial issues. This was signed by Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Grigori Sokolnikov, the Commissar of Finance, and Nadezhda Krupskaya, the widow of Lenin. Stalin rejected this idea and continued to have complete control over government policy. (4)

On the advice of Nikolay Bukharin, all restrictions upon the leasing of land, the hiring of labour and the accumulation of capital were removed. Bukharin's theory was that the small farmers only produced enough food to feed themselves. The large farmers, on the other hand, were able to provide a surplus that could be used to feed the factory workers in the towns. To motivate the kulaks to do this, they had to be given incentives, or what Bukharin called "the ability to enrich" themselves. (5) The tax system was changed in order to help kulaks buy out smaller farms. In an article in Pravda, Bukharin wrote: "Enrich yourselves, develop your holdings. And don't worry that they may be taken away from you." (6)

At the 14th Congress of the Communist Party in December, 1925, Gregory Zinoviev spoke up for others on the left when he declared: "There exists within the Party a most dangerous right deviation. It lies in the underestimation of the danger from the kulak - the rural capitalist. The kulak, uniting with the urban capitalists, the NEP men, and the bourgeois intelligentsia will devour the Party and the Revolution." (7) However, when the vote was taken, Stalin's policy was accepted by 559 to 65. (8)

Expulsion of the Left

In September 1926 Stalin threatened the expulsion of Yuri Piatakov, Leon Trotsky, Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Mikhail Lashevich and Grigori Sokolnikov. On 4th October, these men signed a statement admitting that they were guilty of offences against the statutes of the party and pledged themselves to disband their party within the party. They also disavowed the extremists in their ranks who were led by Alexander Shlyapnikov. However, having admitted their offences against the rules of discipline, they "restated with dignified firmness their political criticisms of Stalin and Bukharin." (9)

Stalin appointed his old friend, Gregory Ordzhonikidze, to the presidency of the Central Control Commission in November 1926, where he was given responsibility for expelling the Left Opposition from the Communist Party. Ordzhonikidze was rewarded by being appointed to the Politburo in 1926. He developed a reputation for having a terrible temper. His daughter said that he "often got so heated that he slapped his comrades but the eruption soon passed." His wife Zina argued "he would give his life for one he loved and shoot the one he hated". However, others said he had great charm and Maria Svanidze described him as "chivalrous". The son of Lavrenty Beria commented that his "kind eyes, grey hair and big moustache, gave him the look of an old Georgian prince". (10)

Stalin gradually expelled his opponents from the Politburo including Trotsky, Zinoviev and Lashevich. In the spring of 1927 Trotsky drew up a proposed programme signed by 83 oppositionists. He demanded a more revolutionary foreign policy as well as more rapid industrial growth. He also insisted that a comprehensive campaign of democratisation needed to be undertaken not only in the party but also in the soviets. Trotsky added that the Politburo was ruining everything Lenin had stood for and unless these measures were taken, the original goals of the October Revolution would not be achievable. (11)

Stalin and Bukharin led the counter-attacks through the summer of 1927. At the plenum of the Central Committee in October, Stalin pointed out that Trotsky was originally a Menshevik: "In the period between 1904 and the February 1917 Revolution Trotsky spent the whole time twirling around in the company of the Mensheviks and conducting a campaign against the party of Lenin. Over that period Trotsky sustained a whole series of defeats at the hands of Lenin's party." Stalin added that previously he had rejected calls for the expulsion of people like Trotsky and Zinoviev from the Central Committee. "Perhaps, I overdid the kindness and made a mistake." (12)

According to Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996): "The opposition then organized demonstrations in Moscow and Leningrad on November 7. These were the last two open demonstrations against the Stalinist regime. The GPU, of course, knew about them in advance but allowed them to take place. In Lenin's Party submitting Party differences to the judgment of the crowd was considered the greatest of crimes. The opposition had signed their own sentence. And Stalin, of course, a brilliant organizer of demonstrations himself, was well prepared. On the morning of November 7 a small crowd, most of them students, moved toward Red Square, carrying banners with opposition slogans: Let us direct our fire to the right - at the kulak and the NEP man, Long live the leaders of the World Revolution, Trotsky and Zinoviev.... The procession reached Okhotny Ryad, not far from the Kremlin. Here the criminal appeal to the non-Party masses was to be made, from the balcony of the former Paris hotel. Stalin let them get on with it. Smilga and Preobrazhensky, both members of Lenin's Central Committee, draped a streamer with the slogan Back to Lenin over the balcony." (13)

Joseph Stalin argued that there was a danger that the party would split into two opposing factions. If this happened, western countries would take advantage of the situation and invade the Soviet Union. On 14th November 1927, the Central Committee decided to expel Leon Trotsky and Gregory Zinoviev from the party. This decision was ratified by the Fifteenth Party Congress in December. The Congress also announced the removal of another 75 oppositionists, including Lev Kamenev. (14)

The Russian historian, Roy A. Medvedev, has explained in Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971): "The opposition's semi-legal and occasionally illegal activities were the main issue at the joint meeting of the Central Committee and Central Control Commission at the end of October, 1927... The Plenum decided that Trotsky and Zinoviev had broken their promise to cease factional activity. They were expelled from the Central Committee, and the forthcoming XVth Congress was directed to review the whole issue of factions and groups." Under pressure from the Central Committee, Kamenev and Zinoviev agreed to sign statements promising not to create conflict in the movement by making speeches attacking official policies. Trotsky refused to sign and was banished to the remote area of Kazhakstan. (15)

Collective Farms

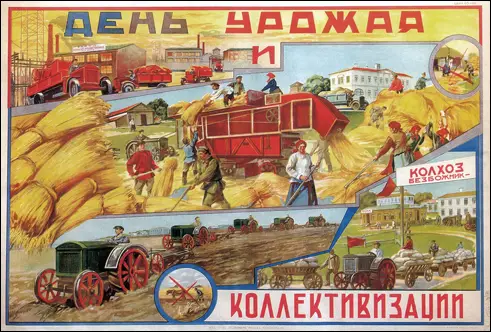

Stalin now decided to turn on the right-wing of the Politburo. He blamed the policies of Nickolai Bukharin for the failure of the 1927 harvest. By this time kulaks made up 40% of the peasants in some regions, but still not enough food was being produced. On 6th January, 1928, Stalin sent out a secret directive threatening to sack local party leaders who failed to apply "tough punishments" to those guilty of "grain hoarding". By the end of the year it was revealed that food production had been two million tons below that needed to feed the population of the Soviet Union. (16)

During that winter Stalin began attacking kulaks for not supplying enough food for industrial workers. He also advocated the setting up of collective farms. The proposal involved small farmers joining forces to form large-scale units. In this way, it was argued, they would be in a position to afford the latest machinery. Stalin believed this policy would lead to increased production. However, the peasants liked farming their own land and were reluctant to form themselves into state collectives. (17)

Stalin was furious that the peasants were putting their own welfare before that of the Soviet Union. Local communist officials were given instructions to confiscate kulaks property. This land was then used to form new collective farms. There were two types of collective farms introduced. The sovkhoz (land was owned by the state and the workers were hired like industrial workers) and the kolkhoz (small farms where the land was rented from the state but with an agreement to deliver a fixed quota of the harvest to the government). He appointed Vyacheslav Molotov to carry out the operation. (18)

Ivar Smilga and Karl Radek gave support to Stalin's policy of collectivization in 1929. As Roy A. Medvedev pointed out: "Stalin produced a split among the Trotskyites in the spring of 1929, when some of them (Smilga and Radek, for example) decided to support Stalin on the grounds that he was adopting their program of an offensive against the kulaks and a swift rate of industrialization. Trotsky himself strongly opposed Stalin's new policies, declaring that they had nothing in common with the earlier proposals of his own group." (18a)

In December, 1929, Stalin made a speech at the Communist Party Congress. He attacked the kulaks for not joining the collective farms. "Can we advance our socialised industry at an accelerated rate while we have such an agricultural basis as small-peasant economy, which is incapable of expanded reproduction, and which, in addition, is the predominant force in our national economy? No, we cannot. Can Soviet power and the work of socialist construction rest for any length of time on two different foundations: on the most large-scale and concentrated socialist industry, and the most disunited and backward, small-commodity peasant economy? No, they cannot. Sooner or later this would be bound to end in the complete collapse of the whole national economy. What, then, is the way out? The way out lies in making agriculture large-scale, in making it capable of accumulation, of expanded reproduction, and in thus transforming the agricultural basis of the national economy." (19)

Stalin then went on to define kulaks as "any peasant who does not sell all his grain to the state". Those peasants who were unwilling to join collective farms "must be annihilated as a class". As the historian, Yves Delbars, pointed out: "Of course, to annihilate them as a social class did not mean the physical extinction of the kulaks. But the local authorities had no time to draw the distinction; moreover, Stalin had issued stringent orders through the agricultural commission of the central committee. He asked for prompt results, those who failed to produce them would be treated as saboteurs." (20)

Local communist officials were given instructions to confiscate kulak property. This land would then be used to form new collective farms. The kulaks themselves were not allowed to join these collectives as it was feared that they would attempt to undermine the success of the scheme. An estimated five million were deported to Central Asia or to the timber regions of Siberia, where they were used as forced labour. Of these, approximately twenty-five per cent perished by the time they reached their destination. (21) According to the historian, Sally J. Taylor: "Many of those exiled died, either along the way or in the makeshift camps where they were dumped, with inadequate food, clothing, and housing." (22)

Ian Grey, in his book, Stalin: Man of History (1982): "The peasants demonstrated the hatred they felt for the regime and its collectivisation policy by slaughtering their animals. To the peasant his horse, his cow, his few sheep and goats were treasured possessions and a source of food in hard times... In the first months of 1930 alone 14 million head of cattle were killed. Of the 34 million horses in the Soviet Union in 1929, 18 million were killed, further, some 67 per cent of sheep and goats were slaughtered between 1929 and 1933." (23)

Walter Duranty, a journalist working for the New York Times, observed the suffering caused by collectivisation: "At the windows haggard faces, men and women, or a mother holding her child, with hands outstretched for a crust of bread or a cigarette. It was only the end of April but the heat was torrid and the air that came from the narrow windows was foul and stifling; for they had been fourteen days en route, not knowing where they were going nor caring much. They were more like caged animals than human beings, not wild beasts but dumb cattle, patient with suffering eyes. Debris and jetsam, victims of the March to Progress." (24)

Riots broke out in several regions and Joseph Stalin, fearing a civil war, and peasants threatening not to plant their spring crop, called a halt to collectivisation. During 1930 this policy led to 2,200 rebellions involving more than 800,000 people. Stalin wrote an article for Pravda where he announced that 55% of USSR agricultural households were working in collective farms. However, he did not reveal that peasant communities in Ukraine, the north Caucasus and central Asia, had taken up arms against collectivization. The Red Army was able to suppress these risings but the resentment felt by rural workers resulted in a decline of productivity. He did attack officials for being over-zealous in their implementation of collectivisation. "Collective farms," Stalin wrote, "cannot be set up by force. To do so would be stupid and reactionary." (25)

He announced that 55% of USSR agricultural households were working in collective farms. However, he did not reveal that peasant communities in Ukraine, the north Caucasus and central Asia, had taken up arms against collectivization. The Red Army was able to suppress these risings but the resentment felt by rural workers resulted in a decline of productivity.

Stalin portrayed himself in the article as the protector of the peasants. Members of the Politburo and local officials were upset that they had been blamed for a policy that had been devised by Stalin. The man who was mainly responsible for the peasants' suffering was now seen as their hero. It was reported that as peasants marched in procession out of their collective farms to return to their own land, they carried large pictures of their saviour, "Comrade Stalin". Within three months of Stalin's article appearing, the numbers of peasants in collective farms dropped from 60 to 25 per cent. It was clear that if Stalin wanted collectivisation, he could not allow freedom of choice. Once again Stalin ordered local officials to start imposing collectivisation. By 1935, 94 per cent of crops were being produced by peasants working on collective farms. The cost to the Soviet people was immense. As Stalin was to admit to Winston Churchill, approximately ten million people died as a result of collectivisation. (26)

Primary Sources

(1) Joseph Stalin, speech (27th December, 1929)

Our large-scale, centralised, socialist industry is developing according to the Marxist theory of expanded reproduction; for it is growing in volume from year to year, it has its accumulations and is advancing with giant strides. But our large-scale industry does not constitute the whole of the national economy. On the contrary, small-peasant economy still predominates in it. Can we say that our small-peasant economy is developing according to the principle of expanded reproduction? No, we cannot. Not only is there no annual expanded reproduction in the bulk of our small-peasant economy, but, on the contrary, it is seldom able to achieve even simple reproduction.

Can we advance our socialised industry at an accelerated rate while we have such an agricultural basis as small-peasant economy, which is incapable of expanded reproduction, and which, in addition, is the predominant force in our national economy? No, we cannot. Can Soviet power and the work of socialist construction rest for any length of time on two different foundations: on the most large-scale and concentrated socialist industry, and the most disunited and backward, small-commodity peasant economy? No, they cannot. Sooner or later this would be bound to end in the complete collapse of the whole national economy.

What, then, is the way out? The way out lies in making agriculture large-scale, in making it capable of accumulation, of expanded reproduction, and in thus transforming the agricultural basis of the national economy.

But how is it to be made large-scale?

There are two ways of doing this. There is the capitalist way, which is to make agriculture large-scale by implanting capitalism in agriculture - a way which leads to the impoverishment of the peasantry and to the development of capitalist enterprises in agriculture. We reject this way as incompatible with Soviet economy.

There is another way: the socialist way, which is to introduce collective farms and state farms into agriculture, the way which leads to uniting the small peasant farms into large collective farms, employing machinery and scientific methods of farming, and capable of developing further, for such farms can achieve expanded reproduction.

And so, the question stands as follows: either one way or the other, either back - to capitalism, or forward - to socialism. There is not, and cannot be, any third way.

The theory of “equilibrium” is an attempt to indicate a third way. And precisely because it is based on a third (non-existent) way, it is utopian and anti-Marxist.

You see, therefore, that all that was needed was to counterpose Marx’s theory of reproduction to this theory of “equilibrium” of the sectors for the latter theory to be wiped out without leaving a trace.

Why, then, do our Marxist students of agrarian questions not do this? In whose interest is it that the ridiculous theory of “equilibrium” should have currency in our press while the Marxist theory of reproduction is kept hidden?

(2) Ian Grey, Stalin: Man of History (1982)

The peasants demonstrated the hatred they felt for the regime and its collectivisation policy by slaughtering their animals. To the peasant his horse, his cow, his few sheep and goats were treasured possessions and a source of food in hard times... In the first months of 1930 alone 14 million head of cattle were killed. Of the 34 million horses in the Soviet Union in 1929, 18 million were killed, further, some 67 per cent of sheep and goats were slaughtered between 1929 and 1933.

(3) Walter Duranty, Write As I Please (1935) page 288

At the windows haggard faces, men and women, or a mother holding her child, with hands outstretched for a crust of bread or a cigarette. It was only the end of April but the heat was torrid and the air that came from the narrow windows was foul and stifling; for they had been fourteen days en route, not knowing where they were going nor caring much. They were more like caged animals than human beings, not wild beasts but dumb cattle, patient with suffering eyes. Debris and jetsam, victims of the March to Progress.

(4) Joseph Stalin, in conversation with Winston Churchill (August, 1942)

It was absolutely necessary for Russia, if we were to avoid periodic famines, to plough the land with tractors. When we gave tractors to the peasants they were all spoiled in a few months. Only collective farms with workshops could handle tractors. We took the greatest trouble to explain it to the peasants. It was no use arguing with them. After you have said all you can to a peasant he says he must go home and consult his wife. After he has talked it over he always answers that he does not want the collective farm and he would rather do without the tractors.

(5) Joseph Stalin, speech (22nd April, 1929)

Comrades Rykov and Bukharin apparently opposed in principle to the application of any kind of emergency measures against the Kulaks... When they want to mask their own line they usually say: "We, of course, are not opposed to pressure being exerted on the Kulak, but we are against the excesses which are being committed"... They then go on to relate stories of the horrors of these excesses, they read you letters from "peasants", panic-stricken letters from comrades... and they then draw the conclusion: the policy of bringing pressure to bear on the Kulaks should be abandoned. How do you like that? It appears that because excesses occur in carrying out a correct policy, the correct policy must be abandoned.

(6) J. N. Westwood, The Soviet Union 1927-41 (1969)

In the year 1932-33 famine raged throughout the richest agricultural regions of the USSR... Five and a half million people died in a man-made disaster unacknowledged by the Soviet leaders. Its principal cause was Stalin's collectivisation drive, which completely disrupted agriculture, and the government's requisition and export of foodstuffs to finance industrialisation. Starvation was compounded with terror - ten million peasants were killed or deported for opposing the state.

(7) Yurij Borisovich Yelagin, Memoirs (1952)

At each town along the way, we saw hundreds and thousands of starving peasants at the station - with their last ounce of strength they had come from their villages in search of a piece of stale bread. They sat against the station walls in long dreary rows, sleeping, dying, and every morning the station guard would have the corpses removed on wagons covered with canvas.

(8) Victor Kravchenko, I Chose Freedom (1947)

On a battlefield men die quickly, they fight back, they are sustained by fellowship and a sense of duty. Here I saw people dying in solitude by slow degrees, dying hideously, without the excuse of sacrifice for a cause. They have been trapped and left to starve, each in his home, by a political decision made in a far-off capital around conference and banquet tables... The most terrifying sights were the little children with skeleton limbs dangling from balloon-like abdomens.

(9) M. Maksudov, USSR 1918 -1958 (1977)

During the famine of 1933-34, an incredible number of children perished, particularly new-born infants. Of those living in the USSR at the time of the 1970 census, 12.4 million persons were born in 1929-31, but only 8.4 million in 1932-34... Bearing in mind... that birth-control methods were virtually unknown in the Russian countryside at that time, it is undoubtedly the case that no fewer than three million children born between 1932 and 1934 died of hunger.

(10) Yemelyan Yaroslavsky, Landmarks in the Life of Stalin (1940)

In a number of districts, there were not a few "Left" distorters of the Party line who decided that explanatory work was superfluous and began to introduce collectivisation in districts where the conditions for it were absolutely unripe... Stalin attacked these dangerous distortions in his article "Dizzy With Success".

(11) Yves Delbars, The Real Stalin (1951)

Stalin felt that the time had come to absolve himself once more from personal responsibility for what was happening... he addressed a severe warning to all those who had been 'intoxicated by the success of the collectivisation and had forgotten the necessity of sparing the peasants unnecessary suffering.'... Stalin thus became to the peasants a sort of 'Little Father,' who listened to their complaints and endeavoured to right their wrongs. The fact that he himself was the immediate origin of their misfortunes was beginning to escape them. An image was taking the place of reality. It is paradoxical fact that these terrible years of collectivisation saw the origin and increase of Stalin's popularity among the Russian peasants.

Student Activities

Russian Revolution Simmulation

Bloody Sunday (Answer Commentary)

1905 Russian Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Russia and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

The Life and Death of Rasputin (Answer Commentary)

The Abdication of Tsar Nicholas II (Answer Commentary)

The Provisional Government (Answer Commentary)

The Kornilov Revolt (Answer Commentary)

The Bolsheviks (Answer Commentary)

The Bolshevik Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject

References

(1) Simon Sebag Montefiore, Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar (2003) page 37

(2) Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (2004) page 229

(3) Isaac Deutscher, Stalin: A Political Biography (1949) page 304

(4) Memorandum submitted to the Central Committee of the Communist Party (October, 1925)

(5) John Simkin, Stalin (1987) page 44

(6) Nikolay Bukharin, Pravda (14th April, 1925)

(7) Gregory Zinoviev, speech, 14th Communist Party Congress (18th December, 1925)

(8) Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin (1996) page 215

(9) Isaac Deutscher, Stalin: A Political Biography (1949) page 310

(10) Sergo Beria, Beria My Father - Inside Stalin's Kremlin (2001) page 15

(11) Leon Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed (1937) pages 556-557

(12) Joseph Stalin, speech Communist Party Congress (October, 1927)

(13) Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin (1996) page 219

(14) Robert Service, Stalin: A Biography (2004) page 250

(15) Roy A. Medvedev, Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971) page 60

(16) John Simkin, Stalin (1987) page 46

(17) Isaac Deutscher, Stalin: A Political Biography (1949) page 314

(18) Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin (1996) page 239

(18a) Roy A. Medvedev, Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism (1971) page 66

(19) Joseph Stalin, speech (27th December, 1929)

(20) Yves Delbars, The Real Stalin (1951) page 162

(21) John Simkin, Stalin (1987) page 47

(22) Sally J. Taylor, Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty (1990) page 163

(23) Ian Grey, Stalin: Man of History (1982) page 250

(24) Walter Duranty, I Write As I Please (1935) page 288

(25) Joseph Stalin, Pravda (2nd March, 1930)

(26) John Simkin, Stalin (1987) page 48