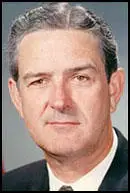

John Connally

John Bowden Connally, one of eight children, was born at Floresville, Texas, on 27th February, 1917. After obtaining a law degree from the University of Texas he joined the staff of Lyndon B. Johnson as legislative assistant.

In December, 1940, Connally married Idanell (Nellie) Brill of Austin. Over the next few years the couple had four children. During the Second World War he joined the U.S. Navy and served as a fighter director aboard aircraft carriers in the Pacific. By the end of the war Connally had reached the rank of lieutenant commander.

A member of the Democratic Party, Connally continued to help run the political campaigns of Lyndon B. Johnson. In 1948 he was accused of being involved in a voting scandal when 200 votes for Johnson arrived late from Jim Wells County. It was these votes that gave Johnson an eighty-seven-vote victory.

Connally became a member of what became known as the Suite 8F Group. The name comes from the room in the Lamar Hotel in Houston where they held their meetings. Members of the group included Lyndon B. Johnson, George Brown and Herman Brown (Brown & Root), Jesse H. Jones (multi-millionaire investor in a large number of organizations and chairman of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation), Gus Wortham (American General Insurance Company), Robert Kerr (Kerr-McGee Oil Industries), James Slither Abercrombie (Cameron Iron Works), William Hobby (Governor of Texas), Richard Russell (chairman of the Committee of Manufactures, Committee on Armed Forces and Committee of Appropriations) and Albert Thomas (chairman of the House Appropriations Committee). Alvin Wirtz and Edward Clark, were also members of the Suite 8F Group.

Connally also ran a radio station in Austin and also worked as legal counsel to oilman Sid Richardson (1951-59). When John F. Kennedy was elected president he appointed Connally as Secretary of the Navy. He held the post until being elected Governor of Texas in January, 1963.

On 22nd November, 1963, President John F. Kennedy arrived in Dallas. It was decided that Kennedy and his party, including his wife, Jacqueline Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Governor John Connally and Senator Ralph Yarborough, would travel in a procession of cars through the business district of Dallas. A pilot car and several motorcycles rode ahead of the presidential limousine. As well as Kennedy the limousine included John Connally, his wife Nellie Connally, Roy Kellerman, head of the Secret Service at the White House and the driver, William Greer. The next car carried eight Secret Service Agents. This was followed by a car containing Johnson and Yarborough.

At about 12.30 p.m. the presidential limousine entered Elm Street. Soon afterwards shots rang out. John Kennedy was hit by bullets that hit him in the head and the left shoulder. Another bullet hit John Connally in the back. Ten seconds after the first shots had been fired the president's car accelerated off at high speed towards Parkland Memorial Hospital. Both men were carried into separate emergency rooms. Connally had wounds to his back, chest, wrist and thigh. Kennedy's injuries were far more serious. He had a massive wound to the head and at 1 p.m. he was declared dead.

Nellie Connally, who was sitting next to her husband in the presidential limousine, always maintained that two bullets struck John F. Kennedy and a third hit her husband. "The first sound, the first shot, I heard, and turned and looked right into the President's face. He was clutching his throat, and just slumped down. He Just had a - a look of nothingness on his face. He-he didn't say anything. But that was the first shot. The second shot, that hit John - well, of course, I could see him covered with - with blood, and his - his reaction to a second shot. The third shot, even though I didn't see the President, I felt the matter all over me, and I could see it all over the car."

John Connally agreed with his wife: "Beyond any question, and I'll never change my opinion, the first bullet did not hit me. The second bullet did hit me. The third bullet did not hit me." As the Warren Commission concluded there also was a bullet that missed the car entirely. Some conspiracy theorists argue that if three bullets struck the men, as the Connallys insisted, and a fourth missed, then there must have been a second gunman because no one person could have fired four rounds from Oswald's bolt-action rifle so quickly.

John Connally made a full recovery and was reelected in 1964 and 1966 when he obtained 72% of the vote. During his period of office he was associated with increased spending on education and the library system. He is also credited with developing Texas as a tourist destination. Connally, who was a right-wing member of the Democratic Party, was involved in a long-term dispute with the more left-wing Ralph Yarborough.

After leaving office Connally worked for the law firm of Vinson and Elkins in Houston. He left the Democratic Party and became a member of the Republican Party. He worked closely with President Richard Nixon and in 1971 was appointed Secretary of the Treasury. When Spiro Agnew was forced to resign Connally was expected to be appointed as Vice President. However, eventually the post went to Gerald Ford.

Connally went into business but his reputation was badly damaged when he became involved in a milk-price bribery scandal. In 1975 Connally accused by Jake Jacobsen of taking bribes while working as Secretary of the Treasury. He was defended by Edward Bennett Williams, who managed to prevent the jury from hearing a recording of a conversation that took place between Connally and Richard Nixon in March 1971. On the tape Connally says to Nixon:"It's on my honor to make sure that there's a very substantial amount of oil in Texas that will be at your discretion," the treasury secretary said. "Fine," said Nixon. "This is a cold political deal," Nixon continued. "They're very tough political operators." "And they've got it," Connally said. "They've got it," Nixon agreed. "Mr. President," Connally concluded, "I really think you made the right decision."

Connally was not found guilty. He later said that: "To be accused of taking a goddamned $10,000 bribe offended me beyond all reason." According to Evan Thomas (The Man to See: Edward Bennett Williams): "Among cynics in the firm, there was a sneaking suspicion that Connally's indignation stemmed from the fact that he had been indicted for taking such a small payoff. The joke around the firm was that if the bribe had been $200,000, Williams would have believed the government, since, in Texas politics, $10,000 was a mere tip."

Connally ran for president in 1980 but was defeated for the nomination. Connally was convinced his involvement in the Watergate Scandal was to blame for this poor result and decided to retire from politics.

Doug Thompson later revealed that in 1982 he asked Connally if he was convinced that Lee Harvey Oswald fired the gun that killed John F. Kennedy. "Absolutely not," Connally said. "I do not, for one second, believe the conclusions of the Warren Commission." Thompson asked why he had not spoken out about this. Connally replied: "Because I love this country and we needed closure at the time. I will never speak out publicly about what I believe."

In the 1980s Connally started his own real estate company. He did very well at first but at the end of the decade he was forced to declare bankruptcy and held a highly publicized auction of his belongings.

John Connally died of pulmonary fibrosis on 15th June, 1993, at the Methodist Hospital of Houston.

Primary Sources

(1) Hugh Aynesworth, JFK: Breaking the News (2003)

Liberal Ralph Yarborough, for example, detested centrists such as Connally and Johnson - and with some reason. The governor and the vice president were never seen doing the senator any favors. Just the opposite. On this trip they seemed determined to put Yarborough in his place.

Connally was scheduled to host a private reception for JFK at the governor's mansion in Austin that Friday night: Yarborough was absent from the guest list.

Yarborough's response to that snub: "I want everybody to join hands in harmony for the greatest welcome to the President and Mrs. Kennedy in the history of Texas." Then: "Governor Connally is so terribly uneducated governmentally, how could you expect anything else?"

On Thursday afternoon in Houston, Yarborough had defied Kennedy by refusing to ride in the same car with LBJ. He chose instead to be seen with Congressman Albert Thomas. In San Antonio that morning, Secret Service Agent Rufus Youngblood was gently nudging the senator toward Johnson's limo when Yarborough saw Congressman Henry Gonzalez, a political blood brother, and bolted toward him. "Can I ride with you, Henry?" he asked.

That evening, employees at Houston's Rice Hotel heard JFK and LBJ arguing over Yarborough in the presidential suite. Kennedy reportedly informed Johnson in strong terms that he felt Yarborough-who had much better poll numbers in Texas than Kennedy-was being mistreated, and the president was unhappy about that.

(2) The Warren Commission Report (September, 1964)

When Governor Connally called at the White House on October 4 to discuss the details of the visit, it was agreed that the planning of events in Texas would be left largely to the Governor. At the White House, Kenneth O'Donnell, special assistant to the President, acted as coordinator for the trip.

Everyone agreed that, if there was sufficient time, a motorcade through downtown Dallas would be the best way for the people to see their President. When the trip was planned for only 1 day, Governor Connally had opposed the motorcade because there was not enough time. The Governor stated, however, that "once we got San Antonio moved from Friday to Thursday afternoon, where that was his initial stop in Texas, then we had the time, and I withdrew my objections to a motorcade." According to O'Donnell, "we had a motorcade wherever we went," particularly in large cities where the purpose was to let the President be seen by as many people as possible. In his experience, "it would be automatic" for the Secret Service to arrange a route which would, within the time allotted, bring the President "through an area which exposes him to the greatest number of people."

(3) The Warren Commission Report (September, 1964)

Governor Connally testified that he recognized the first noise as a rifle shot and the thought immediately crossed his mind that it was an assassination attempt. From his position in the right jump seat immediately in front of the President, he instinctively turned to his right because the shot appeared to come from over his right shoulder. Unable to see the President as he turned to the right, the Governor started to look back over his left shoulder, but he never completed the turn because he felt something strike him in the back. In his testimony before the Commission, Governor Connally was certain that he was hit by the second shot, which he stated he did not hear.

Mrs. Connally, too, heard a frightening noise from her right. Looking over her right shoulder, she saw that the President had both hands at his neck but she observed no blood and heard nothing. She watched as he slumped down with an empty expression on his face. Roy Kellerman, in the right front seat of the limousine, heard a report like a firecracker pop. Turning to his right in the direction of the noise, Kellerman heard the President say "My God, I am hit," and saw both of the President's hands move up toward his neck. As he told the driver, "Let's get out of here; we are hit," Kellerman grabbed his microphone and radioed ahead to the lead car, "We are hit. Get us to the hospital immediately."

The driver, William Greer, heard a noise which he took to be a backfire from one of the motorcycles flanking the Presidential car. When he heard the same noise again, Greer glanced over his shoulder and saw Governor Connally fall. At the-sound of the second shot he realized that something was wrong, and he pressed down on the accelerator as Kellerman said, "Get out of here fast." As he issued his instructions to Greer and to the lead car, Kellerman heard a "flurry of shots" Within 5 seconds of the first noise. According to Kellerman, Mrs. Kennedy then cried out: "What are they doing to you!" Looking back from the front seat, Kellerman saw Governor Connally in his wife's lap and Special Agent Clinton J. Hill lying across the trunk of the car.

Mrs. Connally heard a second shot fired and pulled her husband down into her lap. Observing his blood-covered chest as he was pulled into his wife's lap, Governor Connally believed himself mortally wounded. He cried out, "Oh, no, no, no. My God, they are going to kill us all." At first Mrs. Connally thought that her husband had been killed, but then she noticed an almost imperceptible movement and knew that he was still alive. She said, "It's all right. Be still." The Governor was lying with his head on his wife's lap when he heard a shot hit the President.At that point, both Governor and Mrs. Connally observed brain tissue splattered over the interior of the car. According to Governor and Mrs. Connally, it was after this shot that Kellerman issued his emergency instructions and the car accelerated.

(4) John Connally, The Warren Report: Part 2, CBS Television (26th June, 1967)

All of the shots came from the same place, from back over my right shoulder. They weren't in front of us, or they weren't at the side of us. There were no sounds like that emanating from those directions.

(5) The Warren Report: Part 2, CBS Television (26th June, 1967)

Walter Cronkite: The most persuasive critic of the single-bullet theory is the man who might be expected to know best, the victim himself, Texas Governor John Connally. Although he accepts the Warren Report's conclusion, that Oswald did all the shooting, he has never believed that the first bullet could have hit both the President and himself.

John Connally: The only way that I could ever reconcile my memory of what happened and what occurred, with respect to the one bullet theory, is that it had to be the second bullet that might have hit us both.

Eddie Barker: Do you believe, Governor Connally, that the first bullet could have missed, the second one hit both of you, and the third one hit President Kennedy?

John Connally: That's possible. That's possible. Now, the best witness I know doesn't believe that.

Eddie Barker: Who is the best witness you know?

John Connally: Nellie was there, and she saw it. She believes the first bullet hit him, because she saw him after he was hit. She thinks the second bullet hit me, and the third bullet hit him.

Nellie Connally: The first sound, the first shot, I heard, and turned and looked right into the President's face. He was clutching his throat, and just slumped down. He Just had a - a look of nothingness on his face. He-he didn't say anything. But that was the first shot.

The second shot, that hit John - well, of course, I could see him covered with - with blood, and his - his reaction to a second shot. The third shot, even though I didn't see the President, I felt the matter all over me, and I could see it all over the car.

So I'll just have to say that I think there were three shots, and that I had a reaction to three shots. And - that's just what I believe.

John Connally: Beyond any question, and I'll never change my opinion, the first bullet did not hit me. The second bullet did hit me. The third bullet did not hit me.

Now, so far as I'm concerned, all I can say with any finality is that if there is - if the single-bullet theory is correct, then it had to be the second bullet that hit President Kennedy and me.

(6) The Houston Chronicle (15th November, 1998)

Nellie Connally, the last surviving passenger of the car in which President Kennedy was assassinated, is reasserting her belief that the Warren Commission was wrong about one bullet striking both JFK and her husband, former Governor John Connally.

"I will fight anybody that argues with me about those three shots," she told Newsweek magazine in its Nov. 23 issue. "I do know what happened in that car. Fight me if you want to."

The Warren Commission concluded in 1964 that one bullet passed through Kennedy's body and wounded Connally, and that a second bullet struck Kennedy's head, killing him. It concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald was the lone gunman.

The Connallys maintained that two bullets struck the president in Dealey Plaza 35 years ago and a third hit the governor. John Connally died in 1993 at age 75.

The Warren Commission concluded there also was a bullet that missed the car entirely. Some conspiracy theorists argue that if three bullets struck the men, as the Connallys insisted, and a fourth missed, then there must have been a second gunman because no one person could have fired four rounds from Oswald's bolt-action rifle so quickly.

Mrs. Connally says in Newsweek that personal notes she wrote a few weeks after the assassination reaffirm her belief of the number of shots.

Mrs. Connally wrote that after hearing the first shot, John Connally turned to his right to look back at Kennedy "and then wheeled to the left to get another look at the President. He could not, so he realized the President had been shot."

Then, she wrote, John Connally "was hit himself by the second shot and said, `My God, they are going to kill us all!'"

According to her notes, that was followed by the third shot that passed through Kennedy's head.

She wrote: "With John in my arms and still trying to stay down ... I felt something falling all over me. ... My eyes saw bloody matter in tiny bits all over the car. Mrs. Kennedy was saying, 'Jack! Jack! They have killed my husband! I have his brains in my hand.' "

(7) Michael Granberry interviewed Nellie Connally for the Dallas Morning News (22nd November, 2003)

"It kept going through my mind like a phonograph record playing over and over and over. But for John, it was even worse. His first night home, he cried out in his sleep. I would just pat him on the shoulder, and he'd go back to sleep. Ten days after, I asked him, 'What is it you dream, dear?' And he said, 'Nellie, somebody's always after me. With a gun.' So I just let him cry out. He did that for a month or six weeks and they were always after him."

Her own waking nightmare "has us all in the car. Everyone's having a wonderful time. Everyone's being so good, and then all of a sudden the horror starts. There is never anything good after that happening in that car. The car is filled with yellow roses, red roses and blood. And pieces of the president's brain."

Connally regrets that President Kennedy's legacy - and, by extension, the nation's - could have been so much brighter in the years ahead. "We were all in our 40s," she says of the passengers in the top car of VIP's. "We all had so much to give."

But Dealey Plaza would come to dictate an entirely different reality.

"For the first time in my life, I feared for my family," she said. "And I never had before. Mark, our youngest, was 11 at the time. There was this wall at the governor's mansion (in Austin) that he loved to walk around. Well, he could no longer walk around that wall. We were afraid somebody would snatch him off of it. Sharon, 14 at the time, could no longer go anywhere without someone going with her. It became, in some ways, a difficult life for us, and for me. And even to this day, I still take a glance behind me, just to make sure."

Governor Connally, who survived his wounds, went on to serve as Treasury secretary in the Nixon administration and ran unsuccessfully for president in 1980. He died in 1993.

Mrs. Connally, who lives in Houston, says Nov. 22 will always be a part of her. "I push it to the back of my head. I can bring it out any time I want, but I know it's not constructive. It was such a sad day. We all wanted to be there to begin with, but if you'd been in that car, believe me, you would never ever want to be there again."

(8) Evan Thomas, Washington Monthly (October, 1991)

Connally's highly publicized trial in the spring of 1975 would reestablish Williams as the nation's preeminent trial lawyer. To his law partners - and to Williams himself - the defense of Connally would be remembered not just as a successful day in court but as a work of art. At the very least, it was a how-to guide for the defense of politicians accused of corruption.

Connally, former secretary of the treasury under Nixon, former governor of Texas, Lyndon Johnson's right-hand man, was not known for humility. The first time the Watergate special prosecutor asked him to testify before the grand jury, he "didn't pay a hell of a lot of attention to it," Connally recalled. The prosecutor was probing political payoffs to the Nixon administration from the milk producers, one of the most generous lobbies in Washington. Had Connally been offered $10,000 by a middleman named Jake Jacobsen to help the milk lobby? Connally dismissed the question. He couldn't recall "a dang thing" about any such conversation. A few months later, however, when he was called again before the grand jury, his memory improved. He had discussed such a contribution with Jacobsen, he conceded, but he swore that he had turned down the money.

The Watergate special prosecutor's office had become omnivorous, but Connally was too busy plotting his own political future to notice. He was on a 36-state speaking tour, a warm-up for a presidential run in 1976, when the grand jury leaks began. Columnist Jack Anderson and Daniel Schorr of CBS reported that Jake Jacobsen was singing to the grand jury, testifying that he had given Connally a $10,000 payoff. It began to dawn on Connally that the relaxed standards common in Texas did not apply in Washington. Watergate had "poisoned the atmosphere," he said.

Williams took Connally's call late on a Friday night in June 1974. "I'm at the Mayflower Hotel," Connally told him. "You've got to come over right now." Taking the first subtle step in his minuet of control, Williams told Connally he would see him--the next morning in Williams's office. Accustomed to lawyers who groveled for their clients, Connally did not realize that Williams would insist on reversing the roles. After the briefest consideration, Williams set his fee: $400,000.

On July 19, Connally was indicted for taking a $10,000 illegal gratuity from Jacobsen and then lying to the grand jury about it. Several weeks later, on the day that Richard Nixon succumbed to the Watergate onslaught and resigned as president, Williams accompanied Connally to the federal courthouse, where he was arraigned and fingerprinted. Afterward, the two men sat in Williams's office watching television as Nixon awkwardly waved from his helicopter and flew off into exile and disgrace. "You could feel what everyone in the office was thinking but nobody was saying," said Mike Tigar, the associate who was helping Williams on the case. Had it not been for the milk fund and the aggressive Watergate prosecutor, Connally believed, he would have been sworn in that day as president of the United States. Before the grand jury called him, Connally had fully expected Nixon to ask him to be his vice president, succeeding Spiro Agnew, who had resigned to avoid bribery charges in 1973. Now Connally faced a jail term, and only Williams could save him.

Williams's initial strategy was the same one he invariably employed in major criminal cases: delay. To mute the reverberations of Watergate, Williams wanted to put as much time as possible between Richard Nixon's resignation and Connally's trial. Williams knew that he could not make the case quietly go away by cutting a favorable deal with the prosecutor. His cagey charm was useless with the prosecutor assigned to the case, Frank Tuerkheimer, an upright and wooden law school professor who was wary of his famous opponent. The judge, however, was a more promising target. Frail and slight, with wispy hair, a pinched face, an arthritic hands, Judge George Hart was a Nixon appointee and Republican hard-liner. A few years before, he had sent Williams a friendly note praising him for his pro-law-and-order remarks during a TV interview...

"To be accused of taking a goddamned $10,000 bribe offended me beyond all reason," Connaly later protested. Among cynics in the firm, there was a sneaking suspicion that Connally's indignation stemmed from the fact that he had been indicted for taking such a small payoff. The joke around the firm was that if the bribe had been $200,000, Williams would have believed the government, since, in Texas politics, $10,000 was a mere tip...

There was no mention of payoffs on the tapes, however, no "smoking gun" - at least not on the tapes the jury heard. The jury was not allowed to hear a recording of a far more damaging conversation that took place between Connally and the president. After the formal meeting on milk price supports broke up that day in March 1971, Connally had asked to speak privately with Nixon. "It's on my honor to make sure that ther's a very substantial amount of oil in Texas that will be at your discretion," the treasury secretary said. "Fine," said Nixon. "This is a cold political deal," Nixon continued. "They're very tough political operators." "And they've got it," Connally said. "They've got it," Nixon agreed. "Mr. President," Connally concluded, "I really think you made the right decision."

In many ways, Jacobsen was just like Bobby Baker, a slick and ubiquitous hanger-on to Lyndon Johnson. He had been a "high-rent valet" for LBJ, picking out the right music to play on the presidential yacht, making sure Johnson's tailor arrived on time. Jacobsen himself was always tanned and carefully groomed. He was honey-voiced, quietly smarmy. "He looks like a guy who has just had his fingernails polished," wrote The Washington Star. He wanted to be seen as a Texas wheeler-dealer but he had grown up a poor Jewish boy in New Jersey. His first name was really Emmanuel, but when he moved to Texas he changed his name to E. Jake Jacobsen; "Manny" had become "Jake." In 1973, Jacobsen went bankrupt, unable to pay $12 million in bills. The same year he was charged with defrauding a savings and loan in San Angelo. Faced with up to 35 years in jail, Jacobsen had made a deal: In exchange for leniency, he would testify against John Connally. He grew solemn: "Have we reached the point in our society where scoundrels can escape their punishment if only they inculpate others? If so we should mark it well. Today it is John Connally. Tomorrow it may be you or me." As he usually did, he quoted from the Bible, likening his cross-examination of Jacobsen to the story of Susanna and the Elders in the Book of Daniel - the "first recorded cross-examination," as he put it. His final plea was straight out of 30 years of closing arguments: "I ask you to lift at last the pain and anguish, the humiliation, the ostracism and suffering, the false accusation, the innuendo, the vilification and slander for John Connally and his family. And if you do, the United States will win the day."

The jury deliberated six hours. The first vote was nine to three to acquit; by day's end, the jury was unanimous.

As Foreman O'Toole read the verdict, Williams grabbed Tigar's leg under the table. "This makes up for the last time," he said in a fierce whisper. The shame of Bobby Baker had been expunged; Williams was, in his own phrase, "numero uno" again. Nellie Connally hugged Williams; her husband thanked the jury and began discussing his political future with reporters.

(9) Doug Thompson, Is Deception the Best Way to Serve Your Country? (30th March, 2006)

The handwritten note lay in the bottom drawer of my old rolltop desk, one I bought for $50 in a junk store in Richmond, VA, 39 years ago.

"Dear Doug & Amy," it read. "Thanks for dinner and for listening." The signature was a bold "John" and the letterhead on the note simply said "John B. Connally" and was dated July 14, 1982.

I met John Connally on a TWA flight from Kansas City to Albuquerque earlier that year. The former governor of Texas, the man who took one of the bullets from the assassination that killed President John F. Kenney, was headed to Santa Fe to buy a house.

The meeting wasn't an accident. The flight originated in Washington and I sat in the front row of the coach cabin. During a stop in Kansas City, I saw Connally get on the plane and settle into a first class seat so I walked off the plane and upgraded to a first class seat right ahead of the governor. I not only wanted to meet the man who was with Kennedy on that day in Dallas in 1963 but, as the communications director for the re-election campaign of Congressman Manuel Lujan of New Mexico, I thought he might be willing to help out on what was a tough campaign.

When the plane was in the air, I introduced myself and said I was working on Lujan's campaign. Connally's face lit up and he invited me to move to the empty seat next to him.

"How is Manuel? Is there anything I can do to help?"

By the time we landed in Albuquerque, Connally had agreed to do a fundraiser for Lujan. A month later, he flew back into New Mexico where Amy and I picked him up for the fundraiser. Afterwards, we took him to dinner.

Connolly was both gracious and charming and told us many stories about Texas politics. As the evening wore on and the multiple bourbon and branch waters took their effect, he started talking about November 22, 1963, in Dallas.

"You know I was one of the ones who advised Kennedy to stay away from Texas," Connally said. "Lyndon (Johnson) was being a real asshole about the whole thing and insisted."

Connally's mood darkened as he talked about Dallas. When the bullet hit him, he said he felt like he had been kicked in the ribs and couldn't breathe. He spoke kindly of Jackie Kennedy and said he admired both her bravery and composure.

I had to ask. Did he think Lee Harvey Oswald fired the gun that killed Kennedy?

"Absolutely not," Connally said. "I do not, for one second, believe the conclusions of the Warren Commission."

So why not speak out?

"Because I love this country and we needed closure at the time. I will never speak out publicly about what I believe."

We took him back to catch a late flight to Texas. He shook my hand, kissed Amy on the cheek and walked up the ramp to the plane.

We saw Connally and his wife a couple of more times when they came to New Mexico but he sold his house a few years later as part of a bankruptcy settlement. He died in 1993 and, I believe, never spoke publicly about how he doubted the findings of the Warren Commission.

Connnally's note serves as yet another reminder that in our Democratic Republic, or what's left of it, few things are seldom as they seem. Like him, I never accepted the findings of the Warren Commission. Too many illogical conclusions.

John Kennedy's death, and the doubts that surround it to this day, marked the beginning of the end of America's idealism. The cynicism grew with the lies of Vietnam and the senseless deaths of too many thousands of young Americans in a war that never should have been fought. Doubts about the integrity of those we elect as our leaders festers today as this country finds itself embroiled in another senseless war based on too many lies.

John Connally felt he served his country best by concealing his doubts about the Warren Commission's whitewash but his silence may have contributed to the growing perception that our elected leaders can rewrite history to fit their political agendas.

Had Connally spoken out, as a high-ranking political figure with doubts about the "official" version of what happened, it might have sent a signal that Americans deserve the truth from their government, even when that truth hurts.