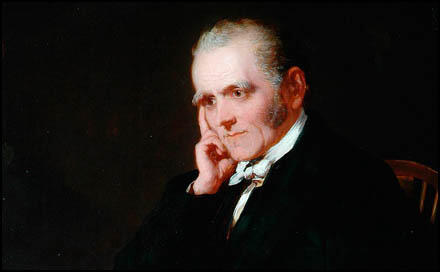

John Fielden

John Fielden, the third son of Joshua Fielden, was born in Todmorden on 17th January, 1784. Joshua Fielden was the owner of a small textile business.

At the age of ten John was required to work in his family's cotton factory for ten hours a day. When he had served his apprenticeship his father made John and his four brothers, partners in Joshua Fielden & Sons. Once a week Joshua and his sons would take their cloth to Manchester, 20 miles away, and collect the bags of imported cotton. This journey became easier with the building of the Rochdale Canal in 1804.

Fielden pointed out: "In the counties of Derbyshire, Nottingham, and, more particularly, in Lancashire the newly-invented machinery was used in large factories built on the side of rivers capable of turning the water-wheel. Thousands of hands were suddenly required in these places, remote from towns. The small and nimble fingers of little children being by far the most in request."

When Joshua Fielden died in 1811, the business was still fairly small. Joshua left £200 in cash and the property and machinery was estimated to be worth £5000. Jointly run by John and his four brothers, Samuel, Joshua, James and Thomas, the business expanded rapidly over the next few years.

John married Ann Grindrod, the daughter of a Rochdale grocer in 1811. The couple had seven children: Jane (1814), Samuel (1816), Mary (1817), Ann (1819), John (1822), Joshua (1827) and Ellen (1829). John Fielden's wife died of a heart-attack in 1831 after seeing a child drown in the local canal.

Brought up as a Quaker, Fielden had been taught at an early age to be concerned about the welfare of the people the company employed. In 1816 the four brothers presented a petition to Parliament that argued for factory legislation to protect child workers. In 1822 Fielden was a founder member of the Todmorden Unitarian Society, a religious group active in the social reform movement. Two years later, Fielden funded the building of the Unitarian Chapel. Fielden also established and taught at the Unitarian School in the village.

When the wages of factory workers began to fall in the 1820s, Fielden started advocating the introduction of a minimum wage. Fielden argued that if workers were paid a decent wage, this would be good for the British economy as it was increase spending on manufactured goods. He also believed that low wages and long hours had a disastrous effect on the health of the workers. As an employer Fielden practised what he preached and paid good wages to his workers. In an attempt to improve wages Fielden gave support to John Doherty and his Grand Union of Operative Spinners. Fielden also worked with Doherty in the formation of the Society for the Protection of Children Employed in Cotton Factories.

Fielden explained in one speech: "At a meeting in Manchester a man claimed that a child in one mill walked twenty-four miles a day. I was surprised by this statement, therefore, when I went home, I went into my own factory, and with a clock beside me, I watched a child at her work, and having watched her for some time, I then calculated the distance she had to go in a day, and to my surprise, I found it to be nothing short of twenty miles."

By 1832 Fielden Brothers was one of the largest textile companies in Britain. The company owned 684 power looms and was responsible for about one per cent of the total cloth being produced in Yorkshire and Lancashire.

John Fielden believed that adult men should have the vote and was active in the Manchester Political Union. He established the Todmorden Political Union and in 1831 Fielden and William Cobbett were selected as Radical candidates for Oldham in the election that followed the passing of 1832 Reform Act. Cobbett and Fielden both won easily and became the leaders of the reform movement in the House of Commons.

After the death of William Cobbett in 1835, reformers relied heavily on John Fielden to put their case in the House of Commons. Campaigns supported by Fielden included the six demands of the Chartist movement and opposition to the 1834 Poor Law Act. Fielden also campaigned against the payment of compensation to slave owners and supported revision of the Corn Laws. Fielden was also in favour of a national system of education under public control and always voted against measures that attempted to give financial aid to church schools.

John Fielden main political activity concerned factory legislation. Although Fielden personally believed that a ten hour day was too long for children, he supported the campaign for a ten hour day as he was aware this was the only thing that Parliament would accept. It was a long hard struggle and it was not until 1847 that Parliament passed the Ten Hours Act. As Lord Ashley had been defeated in the General Election earlier that year, John Fielden had the task of taking the act through Parliament. Although Ashley had been the official leader of the factory reformers, no one had done more than Fielden to obtain this reform.

By the 1840s, John Fielden's son, Samuel Fielden, became the dominant figure in the Fielden Brothers company. In 1845 Fielden purchased a small country estate, Skeynes, near Edenbridge in Kent. John Fielden died at Skeynes on 29th May, 1849. He is buried in a simple grave at the Unitarian Chapel in Todmorden.

Primary Sources

(1) John Fielden, The Curse of the Factory System (1836)

In the counties of Derbyshire, Nottingham, and, more particularly, in Lancashire the newly-invented machinery was used in large factories built on the side of rivers capable of turning the water-wheel. Thousands of hands were suddenly required in these places, remote from towns. The small and nimble fingers of little children being by far the most in request.

(2) Samuel Fielden, Autobiography of Samuel Fielden (1887)

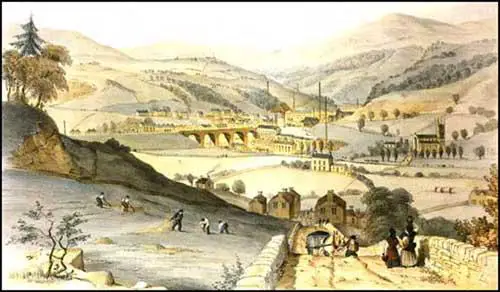

Todmorden lies in a beautiful valley, and on the hillsides are small farms; back about a mile are the moorlands, which could be made into fine farms, as the topography of the moors is more level generally than the enclosed land. But though thousands of starving Englishmen would be very glad to work them, they must be kept for the grouse and the gamekeeper and the gentry. Grouse sport for the privileged classes being esteemed of more importance than the happiness of thousands of human beings. The farms are all dairy, the milk all being sold in town. There are numerous large mills in the town, Fielden Brothers being the largest; it contains about 2,000 looms.

When I arrived at the mature age of 8 years I, as was usual with the poor people's children in Lancashire, went to work in a cotton mill, and if there is any of the exuberance of childhood about the life of a Lancashire mill-hand's child it is in spite of his surroundings and conditions, and not in consequence of it. As I look back on my experience at the tender age I am filled with admiration at the wonderful vitality of these children. I think that if the devil had a particular enemy whom he wished to unmercifully torture the best thing for him to do would be to put his soul into the body of a Lancashire factory child and keep him as a child in a factory the rest of his days. The mill into which I was put was the mill established by John Fielden, M.P., who fought so valiantly in the ten-hour movement.

The infants, when first introduced to these abodes of torture, are put at stripping the full spools from the spinning jennies and replacing them with empty spools. They are put to work in a long room where there are about twenty machines. The spindles are apportioned to each child, and woe be to the child who shall be behind in doing its allotted work. The machine will be started and the poor child's fingers will be bruised and skinned with the revolving spools. while the children try to catch up to their comrades by doing their work with the speed of the machine running, the brutal overlooker will frequently beat them unmercifully, and I have frequently seen them strike the children, knocking them off their stools and sending them spinning several feet on the greasy floor.

When the ten-hour movement was being agitated in England my father was on the committee of agitation in my native town, and I have heard him tell of sitting on the platform with Earl Shaftesbury, John Fielden, Richard Ostler, and other advocates of that cause. I always thought he put a little sarcasm into the word earl, at any rate he had but little respect for aristocracy and royalty. He was also a Chartist and I have heard him tell of many incidents connected with the Chartist agitation and movement.

(3) John Fielden, speech in the House of Commons (9th May, 1836)

At a meeting in Manchester a man claimed that a child in one mill walked twenty-four miles a day. I was surprised by this statement, therefore, when I went home, I went into my own factory, and with a clock beside me, I watched a child at her work, and having watched her for some time, I then calculated the distance she had to go in a day, and to my surprise, I found it to be nothing short of twenty miles.

(4) Charles Wing, Evils of the Factory System (1837)

Mr. Fielden's cotton-mill at Todmorden employs 840 hands. The labour is sixty-seven hours and a half week, being an hour and a half less than most others. No children were employed under nine. A school is attached to the mill. If the liberal management pursued in Mr. Fielden's mill were generally adopted, there would be few evils to complain of.