Hubert Llewellyn Smith

Hubert Llewellyn Smith, the youngest son of Samuel Wyatt Smith, a partner in a wholesale tea business, and his wife, Louisa Scholefield, was born in Bristol on . He was educated at Bristol Grammar School and Corpus Christi College. While at university he became involved in the social reform movement and became a disciple of John Ruskin.

In 1884 an article by Samuel Augustus Barnett in the Nineteenth Century Magazine suggested the idea of university settlements. The idea was to create a place where students from Oxford University and Cambridge University could work among, and improve the lives of the poor during their holidays. According to Barnett, the role of the students was "to learn as much as to teach; to receive as much to give". This article resulted in the formation of the University Settlements Association.

Later that year Barnett and his wife Henrietta Barnett established Toynbee Hall, Britain's first university settlement. Most residents held down jobs in the City, or were doing vocational training, and so gave up their weekends and evenings to do relief work. This work ranged from visiting the poor and providing free legal aid to running clubs for boys and holding University Extension lectures and debates; the work was not just about helping people practically, it was also about giving them the kinds of things that people in richer areas took for granted, such as the opportunity to continue their education past the school leaving age.

Toynbee Hall served as a base for Charles Booth and his group of researchers working on the Life and Labour of the People in London. Other individuals who worked at Toynbee Hall include Llewellyn-Smith, Richard Tawney, Clement Attlee, Alfred Milner, William Beveridge and Robert Morant. Other visitors included Guglielmo Marconi who held one of his earliest experiments in radio there, and Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games, was so impressed by the mixing and working together of so many people from different nations that it inspired him to establish the games. Georges Clemenceau visited Toynbee Hall in 1884 and claimed that Samuel Augustus Barnett was one of the "three really great men" he had met in England.

In 1884 and 1886 Llewellyn Smith obtained a double first in mathematics. His growing interest in politics was shown when he won the Cobden prize for an essay on The Economic Aspects of State Socialism. According to his biographer, R. Norman Davidson: "This reflected a social radicalism that rejected both free-market and socialist dogma. Instead he advocated a mix of ethical and market imperatives in shaping economic and welfare policy." It was clear that he now considered himself to be a socialist. In a speech in Bradford in 1887 he stated that he "would rather be wrong with Karl Marx than right with David Ricardo".

In 1885 Charles Booth became angry about the claim made by H. H. Hyndman, the leader of the Social Democratic Federation, that 25% of the population of London lived in abject poverty. Bored with running his successful business, Booth decided to investigate the incidence of pauperism in the East End of the city. He recruited a team of researchers that included Llewellyn-Smith. His main contribution to the survey concerned the relationship between migration, the labour market, and social deprivation.

The result of Booth's investigations, Life and Labour of the People in London, was published in 1889. Booth's book revealled that the situation was even worse than that suggested by Hyndman. Booth research suggested that 35% rather than 25% were living in abject poverty. Booth now decided to expand his research to cover the rest of London. He continued to run his business during the day and confined his writing to evenings and weekends. In an effort to obtain a comprehensive and reliable survey Booth and his small team of researchers made at least two visits to every street in the city. Over a twelve year period (1891 to 1903) Booth published 17 volumes of the book. Booth argued that the stare should assume responsibility for those living in poverty. One of the proposals he made was for the introduction of Old Age Pensions. A measure that he described as "limited socialism". Booth believed that if the government failed to take action, Britain was in danger of experiencing a socialist revolution.

Samuel Augustus Barnett and Henrietta Barnett carried out their own survey and set out their ideas in the book, Practicable Socialism: Essays on Social Reform (1888). The couple described in detail the poverty they had witnessed in Whitechapel. They concluded the problem was being caused by low wages: "The body's needs are the most exacting; they make themselves felt with daily recurring persistency, and, while they remain unsatisfied, it is hard to give time or thought to the mental needs or the spiritual requirements; but if our nation is to be wise and righteous, as well as healthy and strong, they must be considered. A fair wage must allow a man, not only to adequately feed himself and his family, but also to provide the means of mental cultivation and spiritual development."

The Barnetts argued that the working-class should form trade unions. Llewellyn Smith agreed with this approach and he became increasingly involved in union agitation. In 1888, Clementina Black gave a speech on "Female Labour" at a Fabian Society meeting in London. Annie Besant, a member of the audience, was horrified when she heard about the pay and conditions of the women working at the Bryant & May match factory. The next day, Besant went and interviewed some of the people who were employed by the company. She discovered that the women worked fourteen hours a day for a wage of less than five shillings a week. However, they did not always received their full wage because of a system of fines, ranging from three pence to one shilling, imposed by the Bryant & May management. Offences included talking, dropping matches or going to the toilet without permission. The women worked from 6.30 am in summer (8.00 in winter) to 6.00 pm. If workers were late, they were fined a half-day's pay.

Annie Besant also discovered that the health of the women had been severely affected by the phosphorous that they used to make the matches. This caused yellowing of the skin and hair loss and phossy jaw, a form of bone cancer. The whole side of the face turned green and then black, discharging foul-smelling pus and finally death. Although phosphorous was banned in Sweden and the USA, the British government had refused to follow their example, arguing that it would be a restraint of free trade.

On 23rd June 1888, Beasant wrote an article in her newspaper, The Link. The article, entitled White Slavery in London, complained about the way the women at Bryant & May were being treated. The company reacted by attempting to force their workers to sign a statement that they were happy with their working conditions. When a group of women refused to sign, the organisers of the group was sacked. The response was immediate; 1400 of the women at Bryant & May went on strike. strike.

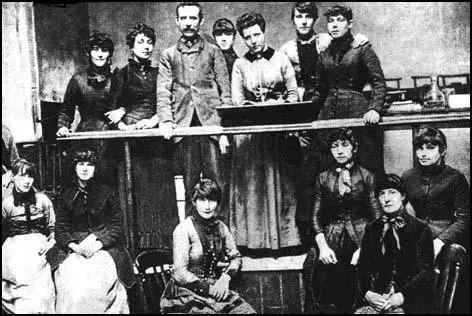

William Stead, the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, Henry Hyde Champion of the Labour Elector and Catharine Booth of the Salvation Army joined Besant in her campaign for better working conditions in the factory. So also did Hubert Llewellyn Smith, Sydney Oliver, Stewart Headlam, Hubert Bland, Graham Wallas and George Bernard Shaw. However, other newspapers such as The Times, blamed Besant and other socialist agitators for the dispute.

Besant, Stead and Champion used their newspapers to call for a boycott of Bryant & May matches. The women at the company also decided to form a Matchgirls' Union and Besant agreed to become its leader. After three weeks the company announced that it was willing to re-employ the dismissed women and would also bring an end to the fines system. The women accepted the terms and returned in triumph. The Bryant & May dispute was the first strike by unorganized workers to gain national publicity. It was also successful at helped to inspire the formation of unions all over the country.

In 1889 Ben Tillett, the General Secretary of the Gasworkers' Union became involved in the London Dock Strike. The dockers demanded four hours continuous work at a time and a minimum rate of sixpence an hour. Tillett soon emerged with Tom Mann and John Burns as one of the three main leaders of the strike. The employers hoped to starve the dockers back to work but people such as Hubert Llewellyn Smith, Will Thorne, Eleanor Marx, James Keir Hardie and Henry Hyde Champion, gave valuable support to the 10,000 men now out on strike. Organizations such as the Salvation Army and the Labour Church raised money for the strikers and their families. Trade Unions in Australia sent over £30,000 to help the dockers to continue the struggle. After five weeks the employers accepted defeat and granted all the dockers' main demands. Llewellyn Smith published The Story of the Dockers' Strike in 1891..

R. Norman Davidson, the author of Whitehall and the Labour Problem in Late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain (1984) has pointed out: "Llewellyn Smith's connections with the trade union movement and with the social scientific community, coupled with his strong involvement with the progressive wing of the Liberal Party, led to his appointment as the first labour commissioner of the Board of Trade in 1893, in charge of a newly established labour department. Although its initial terms of reference were largely that of a statistical bureau, as labour commissioner (1893–7)" It has been argued that along with George Askwith, Llewellyn Smith "laid the foundations for twentieth-century state intervention in British industrial relations".

Hubert Llewellyn Smith helped draft the 1896 Conciliation (Trade Disputes) Act which established a voluntary framework for government conciliation and arbitration in strikes and lock-outs. Llewellyn Smith was also deputy comptroller-general and comptroller-general of the commercial, labour, and statistical branch (1897–1906). Finally he became permanent secretary of the Board of Trade in 1907.

Hubert Llewellyn Smith had married Edith Weekley in 1901. Over the next few years they had four sons and two daughters. He continued to work at the Board of Trade and contributed significantly to the introduction and development of minimum wage legislation under the Trade Boards Act of 1909. To achieve this he had to work closely with Winston Churchill, the president of the Board of Trade, and leading experts in the field of unskilled labour and low-income destitution, including Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, Charles W. Dilke and George Askwith.

Llewellyn Smith was an important figure in the First World War. He was primarily responsible for the economic preparations for war. He devised the valuable system of war-risk insurance and in 1915 organized, under David Lloyd George, the new Ministry of Munitions. He did much to relieve the critical shortage of skilled labour by decentralizing munitions production, ending indiscriminate military recruitment, and securing an agreement with the engineering unions on the wartime suspension of industrial militancy and restrictive practices.

In 1918–19 he headed the British economic section at the Paris Peace Conference and drafted many of the economic provisions of the treaty. In 1919 Llewellyn Smith was elevated to the newly created post of chief economic adviser to the government. He was a strong supporter of the League of Nations, and was the British member of the economic committee from 1920 to 1927. He was also a leading personality in all negotiations affecting international trade and the commercial repercussions of the war. The Labour Party politician, Alfred Salter, claimed that "Hubert Llewellyn Smith... was beyond question one of the great civil servants of his time… who not only administered policy but exercised a powerful influence in its formation".

In 1927 Llewellyn Smith retired from his government post. Over the next few years he organised a survey of working class households in London. It was based at the London School of Economic. The main objective was to measure poverty in city in order to chart the changes in living standards (and other aspects of working class life) since the survey carried out by Charles Booth in the 1880s. The results of the investigation were published in nine volumes between 1930 and 1935 as The New Survey of London Life and Labour.

Hubert Llewellyn Smith died at Church Farmhouse, Tytherington, Wiltshire, on .

Primary Sources

(1) Samuel Augustus Barnett and Henrietta Barnett, Practicable Socialism: Essays on Social Reform (1888)

It would be wise to promote the organisation of un-skilled labour. The mass of applicants last winter belonged to this class, and in one report it is distinctly said that the greater number were born within the demoralising influence of the intermittent and irregular employment given by the Dock Companies, and who have never been able to rise above

their circumstances... If, by some encouragement, these men could be induced to form a union, and if by some pressure the Docks could be induced to employ a regular gang, much would be gained. The very organisation would be a lesson to these men in self-restraint and in fellowship. The substitution of regular hands at the Docks for those who now, by waiting and scrambling, get a daily ticket would give to a large number of men the help of settled employment and take away the dependence on chance which makes many careless.... A possible loss of profit is not comparable to an actual loss of life, and the labourers do lose life and more than life that the dividend or salaries may be increased.

(2) Annie Besant, The Link (23rd June, 1888)

Born in slums, driven to work while still children, undersized because under-fed, oppressed because helpless, flung aside as soon as worked out, who cares if they die or go on to the streets provided only that Bryant & May shareholders get their 23 per cent and Mr. Theodore Bryant can erect statutes and buy parks?

Girls are used to carry boxes on their heads until the hair is rubbed off and the young heads are bald at fifteen years of age? Country clergymen with shares in Bryant & May's draw down on your knee your fifteen year old daughter; pass your hand tenderly over the silky clustering curls, rejoice in the dainty beauty of the thick, shiny tresses.