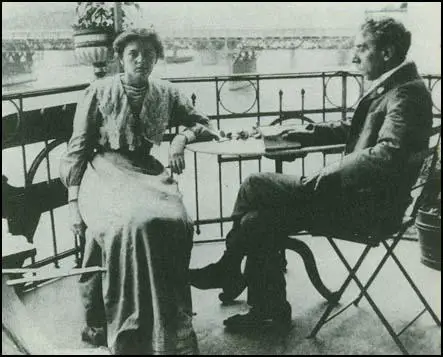

Edith Zangwill

Edith Ayrton, the daughter of the physicist William Edward Ayrton and Matilda Chaplin Ayrton, was born in 1879. Her mother had been a doctor and a member of the London National Society for Women's Suffrage, but died in 1883.

In 1885 Edith's father married Hertha Ayrton. Her stepmother was an important scientist and worked from a laboratory in her house. She was also an active member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.

According to Joseph Udelson, the author of Dreamer of the Ghetto (1990), Hertha Ayrton sent copies of Edith's early short stories to the successful novelist Israel Zangwill. Hertha said to her stepdaughter, "it is very good of him (Zangwill) to look after them, and very nice of him to write to you every day, though I cannot say I think he displays a large amount of self-denial in this. I have no doubt he gets some small modicum of enjoyment out of it, too."

Edith attended Bedford College before marryingIsrael Zangwill, in November 1903. With her husband's encouragement she published a novel, Barbarous Babe in 1904. This was followed by The First Mrs Mollivar (1905). Edith shared her stepmother's support for women's suffrage and became a member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.

The couple had three children: George (born 1906), who became an engineer and worked in Mexico; Margaret (1910), who suffered from a mental condition and was institutionalized and Oliver (1913), who became professor of experimental psychology at the University of Cambridge.

Frustrated by the lack of progress in achieving the vote Edith and Hertha Ayrton accepted that a more militant approach was needed and in 1907 they joined the Women Social & Political Union. In a letter she wrote to Maud Arncliffe Sennett, Hertha admitted: "I made up my mind some time ago that as I am unable to be militant myself, from reasons of health, and as I believe most fully in the necessity for militancy, I was bound to give every penny I can afford to the militant union that is bearing the brunt of the battle, namely the WSPU."

On 9th February 1907, Israel Zangwill shared a platform with Keir Hardie on the subject of women's suffrage. Sylvia Pankhurst recorded: "When Mr. Zangwill came to speak, he.... declared himself to be a supporter of the militant tactics and the anti-Government policy, and the same Liberal ladies (who had hissed Keir Hardie), although they had themselves asked him to speak for them, expressed their dissent and disapproval as audibly as though they had been Suffragettes and he a Cabinet Minister."

Zangwill was criticised for supporting the militant tactics of the Women Social & Political Union. To the charge that members were "unwomanly" he replied that "ladylike means are all very well if you are dealing with gentlemen; but you are dealing with politicians". He added that "for every government - Liberal or Conservative - that refuses to grant female suffrage is ipso facto the enemy."

Hertha Ayrton was left a considerable amount of money by Barbara Bodichon and she gave generously to the WSPU. The 1909-10 WSPU accounts show that she gave £1,060 in that year. In March 1912 the British government made it clear that they intended to seize the assets of the WSPU. According to Evelyn Sharp Hertha Ayrton helped to "launder" through her bank account the funds of the WSPU. The WSPU bank manager was subpoenaed to appear at the conspiracy trial and revealed that £7,000 had been paid to "someone named Ayrton".

In November 1912 Edith Zangwill helped form the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage. The main objective was "to demand the Parliamentary Franchise for women, on the same terms as it is, or may be, granted to men." One member wrote that "it was felt by a great number that a Jewish League should be formed to unite Jewish Suffragists of all shades of opinions, and that many would join a Jewish League where, otherwise, they would hesitate to join a purely political society." Other members included Henrietta Franklin, Hugh Franklin, Lily Montagu, Inez Bensusan and Israel Zangwill.

Militants in the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage disrupted Sabbath worship services in several synagogues in London from early 1913 until the outbreak of First World War, demanding religious as well as political suffrage for women. These women were forcibly removed from synagogues for disrupting services and castigated in the Anglo-Jewish press as “blackguards in bonnets.”

In February 1914 Edith became a leading member of the United Suffragists. The group were disillusioned by the lack of success of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and disapproved of the arson campaign of the Women Social & Political Union, decided to form a new organisation. Membership was open to both men and women, militants and non-militants. Members included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Evelyn Sharp, Henry Nevinson, Margaret Nevinson, Hertha Ayrton, Israel Zangwill, Lena Ashwell, Louisa Garrett Anderson, Eveline Haverfield, Maud Arncliffe Sennett, John Scurr, Julia Scurr and Laurence Housman.

In 1924 Edith Zangwill published the novel, The Call. It was dedicated "To all those who fought for the Freedom of Women". The story tells of a woman scientist who is also a militant suffragette and the character is clearly based on the life of her step-mother, Hertha Ayrton. Her final novel, The House, was published in 1928.

Edith Zangwill died in 1945.

Primary Sources

(1) Joseph Udelson, Dreamer of the Ghetto (1990)

It was the young author Edith Chaplin Ayrton whom Israel Zangwill would eventually choose to marry. She was the daughter of two quite remarkable people, William E. Ayrton and his first wife, Matilda Chaplin. W. E. Ayrton was a prominent electrical engineer and physicist who in 1871 wed his cousin, a pioneering woman medical doctor in Britain; she had, in fact, been encouraged by her feminist husband to enter this profession. Edith, the couple's only child, born 1 October 1875, was prematurely orphaned of her mother when the latter died in 1883. Two years later Ayrton married his Jewish student, Phoebe Sarah (Hertha) Marks.

Miss Marks was a remarkable woman. Born in 1854 in Portsea, at the age of nine she was sent to live in London with her mother's sister; this aunt, Marion (Moss) Hartog, ran a school and wrote several undistinguished books of poetry and of Jewish history. During the course of her girlhood, Hertha, as Miss Marks preferred to be called, abandoned Jewish religious practices, although not the ethnic label. Through the Hartogs she became acquainted with Barbara Leigh-Smith, Madame Bodichon, a cousin of Florence Nightingale, founder of Girton College, Cambridge, a leading figure in the women's movement, and a confidante of George Eliot. In 1873 Madame Bodichon introduced Hertha to the renowned author, who took an interest in her and endeavored to further her education. This latter acquaintance later occasioned rumors that Mirah, the Jewish heroine of Daniel Deronda, was modeled on Hertha, an opinion no longer seriously entertained.

In 1876 Hertha entered Cambridge, where she concentrated her studies on the physical sciences. During the course of these studies she became acquainted with Professor W. E. Ayrton, and in 1885 the two married, much to the consternation of Hertha's widowed mother, who disliked her daughter's intermarrying. The couple then moved to London, where Hertha began lecturing and writing on the theory of electricity. There she also became a prominent suffragette, and to this movement she eventually attracted her stepdaughter, Edith, and her own daughter, Barbara, who had married the poet and author Gerald Gould. In the suffragette campaigns the three worked closely with Christabel Pankhurst, although only Barbara was an activist in the more militant Women's Social and Political Union founded by Pankhurst in 1906.

The Ayrtons first became acquainted with Israel Zangwill at a reception for the famous writer given by the Hartogs in 1895. Edith Ayrton, a budding author attending Bedford College, and Zangwill soon became friends.

By 1901 Hertha, having sent copies of Edith's early short stories to Zangwill, coyly wrote her stepdaughter: "it is very good of him (Zangwill) to look after them, and very nice of him to write to you every day, though I cannot say I think he displays a large amount of self-denial in this. I have no doubt he gets some small modicum of enjoyment out of it, too."

Israel and Edith were married in a civil ceremony at the London registry office on 26 November 1903. Prior to the honeymoon in Spain, a reception for the newlyweds was hosted by the Ayrtons and attended by Zangwill's closest literary friends, Jerome K. Jerome and T. Hall Crane. Notable from the guest list is the absence of most of the groom's Jewish associates.