Wladyslaw Moes

Władysław Moes was born near Wierbka, in southern Poland, on 17th November, 1900. He was the second son of the six children of Count Aleksander Juliusz Moes and his wife Countess Janina Miączyńska. The family was a large landowner and lived in Moes Palace.

In the summer of 1911 the Moes family were on holiday in Venice. Also staying at the Hotel des Bains was the author Thomas Mann. He later admitted that he became fascinated by the ten-year-old Moes "dressed in a sailor suit and of unusual beauty". (1)

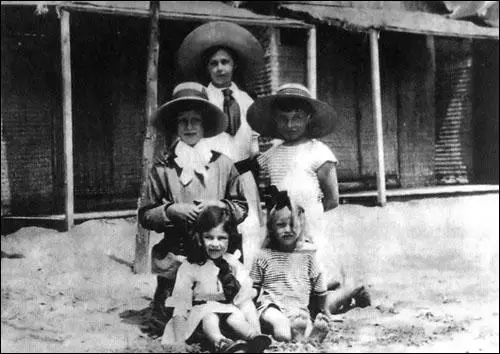

Thomas Mann's wife, Kania, later recalled: "In the dining-room, on the very first day, we saw the Polish family, which looked exactly the way my husband described them: the girls were dressed rather stiffly and severely, and the very charming, beautiful boy of about 13 was wearing a sailor suit with an open collar and very pretty lacings. He caught my husband's attention immediately. This boy was tremendously attractive, and my husband was always watching him with his companions on the beach. He didn't pursue him through all of Venice - that he didn't do but the boy did fascinate him, and he thought of him often." (2) Wladyslaw Moes confirmed that he was aware that while at the hotel he was conscious of an "old man" watching them attentively. (3)

Mann heard rumours that there was cholera in the city. British travel agent advises him to leave straight away. He agrees that this is the safest option and booked tickets to take him back to Pola. On his return to Germany he read about the death of his friend, Gustav Mahler. He then began a new novel about Gustav von Aschenbach, a famous author in his early fifties who has recently been knighted in honor of his artistic achievements. Mann borrowed Mahler's physical features and name for his main character. However, most critics believe the man is actually based on himself. "He lent to Aschenbach many of his intimate personal habits: the three morning hours devoted to writing, the essential midday nap, the indispensable teatime, the afternoon walk that would refresh him for his evening bout of letter writing... He also allotted to Aschenbach his special tenderness for prepubescent boys." (4)

Janek Fudowski (top) and his three sisters in Venice (1911)

Thomas Mann wrote to his friend, Philip Witkop, that during his holiday he had been working on a new novel "serious and pure in tone, concerning a case of pederasty in an aging artist. You will say: hum, hum, but it is very decent". (5) Richard Winston, who has studied Mann's diaries, and believes the story had been developing for some time as "he had long been intrigued by the concept of an older man who has given himself single mindedly to high achievements, only to be seized late in life by love of an inappropriate object who will prove his downfall." (6)

The boy in Death in Venice, Tadzio, is the boy in the sailor suit he saw in the Hotel des Bains. Mann later acknowledged: "Nothing is invented in Death in Venice.... The dreary Pola boat, the grey-haired rake, the sinister gondolier, Tadzio and his family, the journey interrupted by a mistake about the luggage, the cholera, the upright clerk at the travel bureau, the rascally ballad singer, all that and anything else you like, they were all there. I had only to arrange them when they showed at once and in the oddest way their capacity as elements of composition." (7)

The critic, Erich Heller, has successfully summarized the story in the following way: "The writer Gustave von Aschenbach tired by years of uninterrupted work, decides to travel. His journey leads him to Venice. Guests at the same Lido hotel are a Polish family. The youngest child, a boy of about fourteen called Tadzio, strikes Aschenbach as possessing perfect beauty. His admiration gradually grows into passion. As he keeps the secret of his love, so Venice seeks to guard its own: a spreading epidemic of Asiatic cholera. Yet Aschenbach discovers it. Instead of warning the Polish family and departing himself, he yields to the hypnosis of his passion. Staying on, he joins with his own the sinister secret of Venice. With his moral will broken and his soul deranged, he dies on the beach in the sight of Tadzio, who stands Hermes-like on the fringe of the sea, silhouetted against the blue horizon." (8)

The humid weather begins to affect Aschenbach's health, and he decides to leave Venice. On the morning of his planned departure, he sees Tadzio again, and decides to stay. Over the next days and weeks, Aschenbach's interest in the beautiful boy develops into an obsession. He watches him constantly and secretly follows him around the city. A British travel agent warns him that the authorities had suppressed news of a serious cholera epidemic in Venice. Aschenbach considers warning Tadzio's mother of the danger, but eventually decides against this, knowing that if he does, the family will leave the hotel and he will never see the boy again.

Aschenbach strong feelings for the young boy, makes him aware of his aging body. In an attempt to look more attractive, he visits the hotel's barber shop and his face painted to look more youthful. A few days later he discovers the family plan to leave after lunch. He goes down to the beach to his usual deck chair. He sits watching Tadzio, who is looking out to sea. He then turns around and looks at Aschenbach. He thinks he is suggesting he joins him. He tries to rise and follow, only to collapse into his chair where he dies, a victim of cholera.

Death in Venice was initially serialised in a magazine in October and November 1912 and published as a book in February 1913. It received great reviews and was clearly Mann's greatest success since Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family. Over the next few years it would be published in twenty countries, in thirty-seven editions. Anthony Heilbut has argued: "The history of its reception comprises an astonishing chapter of sexual politics... Thus the fact that Mann, a treatise whose subject is a matter of indifference." (9)

Stefan Kanfer has pointed out. "In the novella, the aging Author-Philosopher Gustave Aschenbach seeks renewal in Venice. But like the fugitive with an appointment in Samarra, he finds death awaiting him. An elusive and beautiful youth, Tadzio, attracts the writer. Though he never touches his beloved, never even speaks to him. Aschenbach is rendered immobile by his platonic affair. A plague of cholera racks the city. At any time the writer is free to leave, but he cannot. Eventually, rouged and dyed in imitation of youth, Aschenbach assumes the aspect of a broken clown." Kanfer goes on to argue: "Mann's Death in Venice is, in fact, no more about homosexuality than Kafka's The Metamorphosis is about entomology." (10)

Wladyslaw Moes studied at Saint Stanislaus Kostka's Gymnasium in Warsaw. In 1920 Moes joined the White Army during the Russian Civil War. After the death of his father in 1928 he ran the family estate. In 1935 he married a noblewoman, Anna Belina-Brzozowska. The couple had two children, Aleksander and Maria.

The German Army invaded Poland in September, 1939. Wladyslaw Moes was taken prisoner and sent to Oflag, where he spent the rest of the Second World War.

Joseph Stalin established a communist dominated coalition in Poland after the war. Moes was deprived of his land and he was forced to earn his living mainly as a translator. He later moved to France where he lived with his daughter.

Władysław Moes died in Warsaw on 17th December 1986.

Primary Sources

(1) Katia Mann, Unwritten Memories (1975)

All the details of the story... are taken from experience... In the dining-room, on the very first day, we saw the Polish family, which looked exactly the way my husband described them: the girls were dressed rather stiffly and severely, and the very charming, beautiful boy of about 13 was wearing a sailor suit with an open collar and very pretty lacings. He caught my husband's attention immediately. This boy was tremendously attractive, and my husband was always watching him with his companions on the beach. He didn't pursue him through all of Venice - that he didn't do but the boy did fascinate him, and he thought of him often.

(2) Erich Heller, Thomas Mann: The Ironic German (1958)

The story (Death in Venice) is as well-known as it is simple. The writer Gustave von Aschenbach tired by years of uninterrupted work, decides to travel. His journey leads him to Venice. Guests at the same Lido hotel are a Polish family. The youngest child, a boy of about fourteen called Tadzio, strikes Aschenbach as possessing perfect beauty. His admiration gradually grows into passion. As he keeps the secret of his love, so Venice seeks to guard its own: a spreading epidemic of Asiatic cholera. Yet Aschenbach discovers it. Instead of warning the Polish family and departing himself, he yields to the hypnosis of his passion. Staying on, he joins with his own the sinister secret of Venice. With his moral will broken and his soul deranged, he dies on the beach in the sight of Tadzio, who stands Hermes-like on the fringe of the sea, silhouetted against the blue horizon.

(3) Stefan Kanfer, Time Magazine (5th July, 1971)

Vladimir Nabokov called it "posh-lost," a Russian term he translates as "crude pseudo literature." Thomas Mann called it Death in Venice, perhaps the most celebrated novella of the 20th century.

One can understand the great Russian's distaste for the work of the great German. In the story, the sun does not rise and set; instead "the naked god with cheeks aflame drove his four fire-breathing steeds through heaven's spaces." Venice is not a city, but "the fallen Queen of the Seas." The symbolism accompanying the dense, involuted prose is no less affected. But Death in Venice works, as a tale, a moral instruction and as art. Of all authors, Mann was the least ingenuous. He deliberately chose the Romantic mode to bid adieu to the romantic mood. Through the spacious andante of Death in Venice, one can hear the contrapuntal knell of the 19th century with all its values, poses and styles.

In his film adaptation, Luchino Visconti (The Damned) pays his utmost disrespect to the original by maintaining Mann's fustian and removing his intention. In the novella, the aging Author-Philosopher Gustave Aschenbach seeks renewal in Venice. But like the fugitive with an appointment in Samarra, he finds death awaiting him. An elusive and beautiful youth, Tadzio, attracts the writer. Though he never touches his beloved, never even speaks to him.

Aschenbach is rendered immobile by his platonic affair. A plague of cholera racks the city. At any time the writer is free to leave, but he cannot. Eventually, rouged and dyed in imitation of youth, Aschenbach assumes the aspect of a broken clown. At beachside, he finally succumbs, still gazing at the elusive figure of Tadzio. "And before nightfall a shocked and respectful world received the news of his decease."

Those events would be difficult to render in the best of cinematic circumstances. Director Visconti provides the worst. Mann is supposed to have based his hero on Gustav Mahler. So Visconti, ruthlessly deleting Mann's imagination, makes the neoclassic author a Romantic musician - accompanied by plaintive strains of Mahler's Fifth Symphony, emphasized until it becomes as banal as the theme from Love Story. Mann's Aschenbach was a harrowed spent figure with a dead wife and a grown daughter. Visconti's is played by Dirk Bogarde, a man barely into middle age. Accordingly, he is equipped, like Mahler, with a young wife and a deceased child.

Most important, Mann's treatment of the unconsummated affair of man and boy was a metaphor for Europe's decaying society. But Visconti takes the veneer and calls it furniture. With infinite tedium, he pores over every facet of Tadzio's Botticelli visage; with stupid distortion, he makes the boy, played by Bjorn Andresen, a flirt whose eyes flash a come-on to his helpless elder, like some midnight cowboy off the Via Veneto. He even concocts an elaborate bordello scene in which Aschenbach is shown as a heterosexual failure - a moment that proves as barren of meaning as it is of style.

It must be acknowledged that even at his worst, Visconti remains a master of surfaces. The city's astonishing Adriatic streets, its gleaming planes and squares have never been so lovingly rendered. The epoch, with beautiful women haloed by immense hats and men elegantly attired merely for a saunter through the palm court, is flawlessly but tediously recreated. Still, there is no substance beneath the moving images. Adolescent Bjorn Andresen is properly androgenous but no more mysterious than a lump of sugar. Dirk Bogarde is miscast and misdirected - all hurt looks and empty cackle. The prize for most voluble player must, however, go to Mark Burns as the musician's friend. Invented for the film, he shrieks such Viscontian art-and-life lines as "Do you know what lies at the bottom of the mainstream? Mediocrity!"

This film is worse than mediocre; it is corrupt and distorted. It is one thing to change an author's lines or his characters. It is quite another to destroy his soul. Mann's Death in Venice is, in fact, no more about homosexuality than Kafka's The Metamorphosis is about entomology. Visconti's poshlost may aspire to tragedy, but it does not even achieve melancholia; it is irredeemably, unforgivably gay.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the German Workers' Party (Answer Commentary)

Sturmabteilung (SA) (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler the Orator (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)