Wall Street Crash

The United States entered the 1920's in a strong economic position. The economies of her European rivals had been severely disrupted by the First World War and the United States had been able to capture markets which had previously been supplied by countries like Britain, France and Germany.

However, some of the improvements in the American economy that had taken place could be traced back to changes that took place before the war. Henry Ford moved his operations to the specially built Highland Park Ford Plant. Over 120 acres in size it was the largest manufacturing facility in the world at the time of its opening. In 1913, the Highland Park Ford Plant became the first automobile production facility in the world to implement the assembly line. (1)

Ford had been influenced by the ideas of Frederick Winslow Taylor who had published his book, Scientific Management in 1911. Peter Drucker has pointed out: "Frederick W. Taylor was the first man in recorded history who deemed work deserving of systematic observation and study." (2) Ford took on Taylor's challenge: "It is only through enforced standardization of methods, enforced adoption of the best implements and working conditions, and enforced cooperation that this faster work can be assured. And the duty of enforcing the adoption of standards and enforcing this cooperation rests with management alone." (3)

Initially it had taken 14 hours to assemble a Model T car. By improving his mass production methods, Ford reduced this to 1 hour 33 minutes. This lowered the overall cost of each car and enabled Ford to undercut the price of other cars on the market. By 1914 Ford had made and sold 250,000 cars. Those manufactured amounted for 45% of all automobiles made in the USA that year. (4)

Fordism

On 5th January 1914, on the advice of James Couzens, the Ford Motor Company announced that the following week, the work day would be reduced to eight hours and the Highland Park factory converted to three daily shifts instead of two. The basic wage was increased from three dollars a day to an astonishing five dollars a day. This was at a time when the national average wage was $2.40 a day. A profit-sharing scheme was also introduced. This high-production, generous wage system became known as Fordism. (5)

Henry Ford took the credit for this bold move calling it "the greatest revolution in the matter of rewards for workers ever known to the industrial world." (6) The Wall Street Journal complained about the decision. They accused Ford of injecting "Biblical or spiritual principles into a field where they do not belong" which would result in "material, financial, and factory disorganization." (7)

Other industrialists followed Henry Ford's example. Between 1919 and 1929 output per worker increased by 43%. This increase enabled America to produce items that were cheaper than those manufactured by her European competitors. This enabled employers to pay higher wages. One politician pointed out: "I think our people have long realized the advantages of large business operations in improving and cheapening the cost of manufacture and distribution…. The more goods produced, the more share there is to distribute." (8)

By 1926 the average daily wage of a Ford worker was $10 and the Model T sold for only $350. (9) The distribution of this new wealth was very unequal: "The average industrial wage rose from 1919's $1,158 to $1,304 in 1927, a solid if unspectacular gain, during a period of mainly stable prices... The twenties brought an average increase in income of about 35%. But the biggest gain went to the people earning more than $3,000 a year.... The number of millionaires had risen from 7,000 in 1914 to about 35,000 in 1928." (10)

.

The United States also pioneered techniques in persuading people to buy the latest products. The development of commercial radio meant that companies could communicate information about their goods to a mass audience. In order to encourage people to purchase expensive goods like motor cars, refrigerators and washing machines, the system of hire-purchase was introduced which allowed customers to pay for these goods by installments. This had first been introduced by Isaac Merritt Singer in an effort to sell expensive sewing machines. It was known as the Hire Purchase Plan: "By advancing a certain percentage of the total price of the machine, a customer could hire a sewing machine, make monthly payments to it, and eventually own it." Singer only charged $5 for the initial payment, but as soon as they failed to make the monthly payments, the machine was repossessed. This method of selling goods was a great success and sales soared. (11)

Andre Siegfried, a French visitor pointed out: "In America the daily life of the majority is conceived on a scale that is reserved for the privileged classes anywhere else... The use of the telephone, for instance, is very widespread. In 1925 there were 15 subscribers for every 100 inhabitants as compared with 2 in Europe, and some 49,000,000 conversations per day.... Wireless is rapidly winning a similar position for itself, for even in 1924 the farmers alone possessed over 550,000 radios.... Statistics for 1925 show that... the United States owned 81 per cent of all the automobiles in existence, or one for every 5.6 people, as compared with one for every 49 and 54 in Great Britain and France." (12)

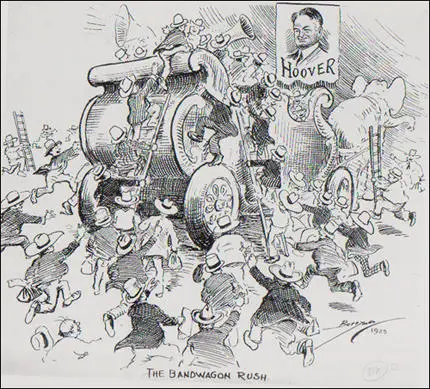

Herbert Hoover and the Economy

The American economy appeared to be in such a healthy state that during the 1928 Presidential Election, the Republican candidate, Herbert Hoover, claimed that: "We in America are nearer to the financial triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of our land. The poor house is vanishing from among us. Under these impulses, and the Republican protective system our industrial output has increased as never before and our wages have grown steadily in buying power. Our workers, with their average weekly wages, can today buy two and even three times more bread and butter than any other earner in Europe." (13)

Herbert Hoover easily defeated Al Smith, the Democratic Party candidate (21,427,123 votes to 15,015,464) in the election. An editorial in the New York Times in January, 1929, quoted President Hoover as saying: "It has been twelve months of unprecedented advance, of wonderful prosperity. If there is any way of judging the future by the past, this New Year will be one of felicitation and hopefulness." (14)

One way of making money during the 1920's was to buy stocks and shares. Prices of these stocks and shares constantly went up and so investors kept them for a short-term period and then sold them at a good profit. As with consumer goods, such as motor cars and washing machines, it was possible to buy stocks and shares on credit. This was called buying on the "margin" and enabled "speculators" to sell off shares at a profit before paying what they owed. In this way it was possible to make a considerable amount of money without a great deal of investment. During the first week of December, 1927, "more shares of stock had changed hands than in any previous week in the whole history of the New York Stock Exchange." (15)

The share price of Montgomery Ward, the mail-order company, went from $132 on 3rd March, 1928, to $466 on 3rd September, 1928. Whereas Union Carbide & Carbon for the same period went from $145 to $413; American Telephone & Telegraph from $77 to $181; Westinghouse Electric Corporation from $91 to $313 and Anaconda Copper from $54 to $162. (16)

John J. Raskob, a senior executive at General Motors, published an article, Everybody Ought to be Rich in August, 1929, where he pointed out: "The common stocks of their country have in the past ten years increased enormously in value because the business of the country has increased. Ten dollars invested ten years ago in the common stock of General Motors would now be worth more than a million and a half dollars. And General Motors is only one of may first-class industrial corporations." He then went on to say: "If a man saves $15 a week, and invests in good common stocks, and allows the dividends and rights to accumulate, at the end of twenty years he will have at least $80,000 and an income from investments of around $400 a month. He will be rich. And because income can do that, I am firm in my belief that anyone not only can be rich, but ought to be rich." (17)

Cecil Roberts, a British journalist working in the United States, pointed out that the stock market hysteria reached its apex in the summer of 1929. "Everyone gave you tips for a rise. Every was playing the market. Stocks soared dizzily. I found it hard not to be engulfed. I had invested my American earnings in good stocks. Should I sell for a profit? Everyone said, 'Hang on - it's a rising market'. On my last day in New York I went down to the barber. As he removed the sheet he said softly, 'Buy Standard Gas. I've doubled. It's good for another double.' As I walked upstairs, I reflected that if the hysteria had reached the barber-level, something must soon happen." (18)

Alec Wilder, the songwriter, became concerned about the value of his shares: "I knew something was terribly wrong because I heard bellboys, everybody, talking about the stock market. In August 1929 I persuaded my mother in Rochester to let me talk to our family adviser. I wanted to sell stock which had been left me by my father.... I talked to this charming man and told him I wanted to unload this stock. Just because I had this feeling of disaster. He got very sentimental: 'Oh your father wouldn't have liked you to do that.' He was so persuasive, I said O.K. I could have sold it for $160,000. Four years later, I sold it for $4,000." (19)

Wall Street Crash

On 3rd September 1929 the stock market reached an all-time high. In the weeks that followed prices began to slowly decline. Later that month, an incident took place in London that caused major problems on Wall Street. In April 1929 Clarence Hatry, the former owner of Leyland Motors, acquired control of United Steel by borrowing "£789,000 from banks on the security of forged Corporation and General scrip certificates ascribed to the municipalities of Gloucester, Wakefield, and Swindon. £822,000 was withheld from these three corporations and another £700,000 was raised by duplicating shares in other companies he had promoted. As rumours about the Hatry companies circulated in the City, he spent large sums vainly trying to support their share values." (20)

On 20th September Hatry voluntarily confessed his frauds to Sir Archibald Bodkin, director of public prosecutions. The economist John Kenneth Galbraith, described Hatry as "one of those curiously un-English figures with whom the English periodically find themselves unable to cope." (21) The news of this corrupt activity caused the London Stock Exchange to crash. This greatly weakened the optimism of American investment in markets overseas and caused further falls in the value of shares on Wall Street. (22)

Efforts were made to regain confidence in the state of the American economy. Irving Fisher, professor of political economy at Yale University, was considered the most important economist of the 1920s. His research on the quantity theory of money inaugurated the school of macroeconomic thought known as monetarism. On 17th October, 1929 he was reported as telling the Purchasing Agents Association that stock prices had reached "what looks like a permanently high plateau". He added that he expected to see the stock market, within a few months, "a good deal higher than it is today." (23)

Despite Fisher's prediction, on 24th October, over 12,894,650 shares were sold. Prices fell dramatically as sellers tried to find people willing to buy their shares. That evening, five of the country's bankers, led by Charles Edward Mitchell, chairman of the National City Bank, issued a statement saying that due to the heavy selling of shares, many were now under-priced. This statement failed to halt the reduction in demand for shares. (24)

The New York Times reported: "The most disastrous decline in the biggest and broadest stock market of history rocked the financial district yesterday.... It carried down with it speculators, big and little, in every part of the country, wiping out thousands of accounts. It is probable that if the stockholders of the country's foremost corporations had not been calmed by the attitude of leading bankers and the subsequent rally, the business of the country would have been seriously affected. Doubtless business will feel the effects of the drastic stock shake-out, and this is expected to hit the luxuries most severely." (25)

On the opening of the Wall Street Stock Exchange on 29th October, 1929, John D. Rockefeller, the American oil industry business magnate and successful industrialist, issued a statement which attempted to regain confidence in the state of the economy: "Believing that fundamental conditions of the country are sound and that there is nothing in the business situation to warrant the destruction of values that has taken place on the exchanges during the past week, my son and I have for some days been purchasing sound common stocks." (26)

This did not have the desired impact on the market for that day over 16 million shares were sold. The market had lost 47 per cent of its value in twenty-six days. "Efforts to estimate yesterday's market losses in dollars are futile because of the vast number of securities quoted over the counter and on out-of-town exchanges on which no calculations are possible. However, it was estimated that 880 issues, on the New York Stock Exchange, lost between $8,000,000,000 and $9,000,000,000 yesterday. Added to that loss is to be reckoned the depreciation on issues on the Curb Market, in the over the counter market and on other exchanges." (27)

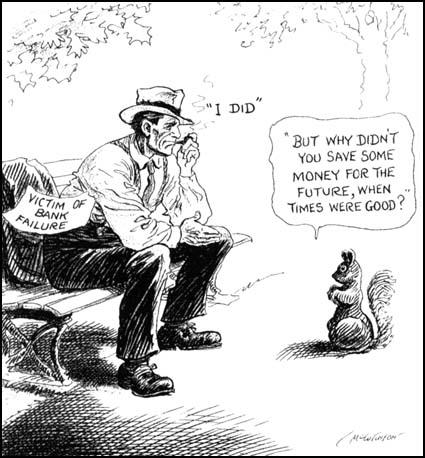

Although less than one per cent of the American people actually possessed stocks and shares, the Wall Street Crash was to have a tremendous impact on the whole population. The fall in share prices made it difficult for entrepreneurs to raise the money needed to run their companies. Frederick Lewis Allen pointed out: "Billions of dollars' of profits - and paper profits - had disappeared. The grocer, the window-cleaner, and the seamstress had lost their capital. In every town there were families which had suddenly dropped from showy affluence into debt. Investors who had dreamed of retiring to live on their fortunes now found themselves back once more at the very beginning of the long road to riches. Day by day the newspapers printed the grim reports of suicides." (28)

Within a short time, 100,000 American companies were forced to close and consequently many workers became unemployed. As there was no national system of unemployment benefit, the purchasing power of the American people fell dramatically. This in turn led to even more unemployment. Yip Harburg pointed out that before the Wall Street Crash, the American citizen thought: "We were the prosperous nation, and nothing could stop us now.... There was a feeling of continuity. If you made it, it was there forever. Suddenly the big dream exploded. The impact was unbelievable." (29)

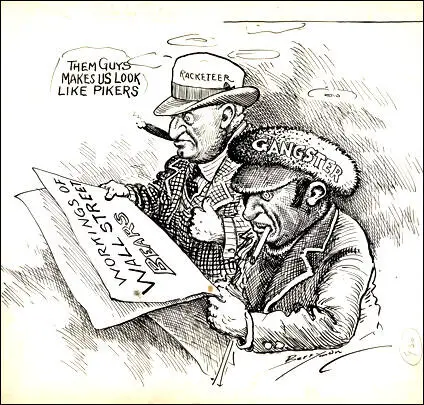

It was later discovered that some Wall Street bankers had been partly responsible for the crash. It was pointed out that from September 1929, Albert H. Wiggin had begun selling short his personal shares in Chase National Bank at the same time he was committing his bank's money to buying. As Michael Perino pointed out: "In the midst of the 1929 crash, Wiggen was part of the group of Wall Street leaders who tried to prop up the market. Or at least that was what the public thought.... Wiggen was actually shorting Chase's stock (in effect betting that the price of the stock would continue to drop) on money borrowed from Chase". He shorted over 42,000 shares, earning him over $4 million. His earning were tax-free since he used a Canadian shell company to buy the stocks. (30)

As William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963) pointed out: "At a time when millions lived close to starvation, and some even had to scavenge for food, bankers like Wiggin and corporation executives like George Washington Hill of American Tobacco drew astronomical salaries and bonuses. Yet many of these men, including Wiggin, manipulated their investments so that they paid no income tax at all. In Chicago, where teachers, unpaid for months, fainted in classrooms for want of food, wealthy citizens of national reputation brazenly refused to pay taxes or submitted falsified statements." (31)

Senator Burton Wheeler of Montana argued: "The best way to restore confidence in the bank would be to take these crooked presidents out of the banks and treat them the same way as we treated Al Capone when he failed to pay his income-tax." Senator Carter Glass of Virginia joked in bad taste: "There is a big scandal down in Georgia. The fact has just been discovered that a white woman is married to a banker." He added that in his state people usually lynched black men, but now they were "lynching bankers." (32)

After the Wall Street Crash, the leading utility magnate, Samuel Insull, fled the United States to France. Insull was the chairman of the boards of sixty-five companies that folded, wiping out the life savings of 600,000 shareholders. When the United States asked French authorities that he be extradited, Insull moved on to Greece, where there was not yet an extradition treaty with the United States. He later moved to Turkey where he was arrested and extradited back to the United States. He was defended by famous Chicago lawyer Floyd Thompson and found not guilty on all counts. (33)

Unemployment

In 1929 only 1.5 million people in the United States were out of work; by 1931 it had reached 8 million. In many areas the situation was even worse than these figures imply. In industrial cities like Chicago, for example, over 40% of the work-force was unemployed. Edmund Wilson observed: "There is not a garbage-dump in Chicago which is not diligently haunted by the hungry. Last summer the hot weather when the smell was sickening and the flies were thick, there were a hundred people a day coming to one of the dumps... a widow who used to do housework and laundry, but now had no work at all, fed herself and her fourteen-year-old son on garbage. Before she picked up the meat, she would always take off her glasses so that she couldn't see the maggots." (34)

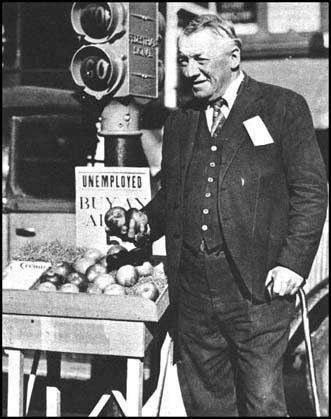

forced to sell apples after the Wall Street Crash.

At first President Herbert Hoover refused to take action, claiming that it was only a temporary problem that American businessmen would eventually solve. Hoover then decided to take dramatic action. He authorized the Mexican Repatriation program to force unemployed Mexican citizens to return home. Estimates of how many were repatriated range from 500,000 to 2,000,000, of whom perhaps 60% were US citizens by birth. As the forced migration was based on race, and ignored citizenship, Kevin Johnson has argued that today this policy would be classified as a form of "ethnic cleansing." (35)

In 1930 President Hoover attempted to give businessmen some help by raising custom duties to record levels. Europe retaliated by increasing its custom duties and this resulted in a further decline in world trade. By 1932 the number of people unemployed reached 12 million. America was in a deep depression and the Hoover administration seemed to have little idea how to solve it. These actions lost Hoover the support of progressive Republicans such as William Borah and undermined his authority in the party. (36)

Primary Sources

(1) Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday (1931)

Throughout 1927 speculation had been increasing. The amount of money loaned to brokers to carry margin accounts for traders had risen during the year from $2,818,561,000 to $3,558,355,000 - a huge increase. During the week of December 3, 1927, more shares of stock had changed hands than in any previous week in the whole history of the New York Stock Exchange. One did not have to listen long to an after-dinner conversation, whether in New York or San Francisco or the lowliest village of the plain, to realize that all sorts of people to whom the stock ticker had been a hitherto alien mystery were carrying a hundred shares of Studebaker or Houston Oil, learning the significance of such recondite symbols as GL and X and ITT, and whipping open the early editions of afternoon papers to catch the 1.30 quotations from Wall Street.

(2) Cecil Roberts, The Bright Twenties (1938)

The stock market hysteria reached its apex in 1929. Everyone gave you tips for a rise. Everyone gave you tips for a rise. Every was playing the market. Stocks soared dizzily. I found it hard not to be engulfed. I had invested my American earnings in good stocks. Should I sell for a profit? Everyone said, "Hang on - it's a rising market". On my last day in New York I went down to the barber. As he removed the sheet he said softly, "Buy Standard Gas. I've doubled. It's good for another double." As I walked upstairs, I reflected that if the hysteria had reached the barber-level, something must soon happen.

(3) John J. Raskob, Everybody Ought to be Rich, Ladies Home Journal (August, 1929)

The common stocks of their country have in the past ten years increased enormously in value because the business of the country has increased. Ten dollars invested ten years ago in the common stock of General Motors would now be worth more than a million and a half dollars. And General Motors is only one of may first-class industrial corporations.

If a man saves $15 a week, and invests in good common stocks, and allows the dividends and rights to accumulate, at the end of twenty years he will have at least $80,000 and an income from investments of around $400 a month. He will be rich. And because income can do that, I am firm in my belief that anyone not only can be rich, but ought to be rich.

(4) Alec Wilder was interviewed by Studs Terkel in Hard Times (1970)

I knew something was terribly wrong because I heard bellboys, everybody, talking about the stock market. About six weeks before the Wall Street Crash, I persuaded my mother in Rochester to let me talk to our family adviser. I wanted to sell stock which had been left me by my father. He got very sentimental: "Oh your father wouldn't have liked you to do that." He was so persuasive, I said O.K. I could have sold it for $160,000. Four years later, I sold it for $4,000.

(5) New York Times (25th October, 1929)

The most disastrous decline in the biggest and broadest stock market of history rocked the financial district yesterday. In the very midst of the collapse five of the country's most influential bankers hurried to the office of J. P. Morgan & Co., and after a brief conference gave out word that they believe the foundations of the market to be sound, that the market smash has been caused by technical rather than fundamental considerations, and that many sound stocks are selling too low.

Suddenly the market turned about on buying orders thrown into the pivotal issues, and before the final quotations were tapped out, four hours and eight minutes after the 3 o'clock bell, most stocks had regained a measurable part of their losses.

The break was one of the widest in the market's history, although the losses at the close were not particularly large, many having been recouped by the afternoon rally.

It carried down with it speculators, big and little, in every part of the country, wiping out thousands of accounts. It is probable that if the stockholders of the country's foremost corporations had not been calmed by the attitude of leading bankers and the subsequent rally, the business of the country would have been seriously affected. Doubtless business will feel the effects of the drastic stock shake-out, and this is expected to hit the luxuries most severely.

The total losses cannot be accurately calculated, because of the large number of markets and the thousands of securities not listed on any exchange. However, they were staggering, running into billions of dollars. Fear struck the big speculators and little ones, big investors and little ones. Thousands of them threw their holdings into the whirling Stock Exchange pit for what they would bring. Losses were tremendous and thousands of prosperous brokerage and bank accounts, sound and healthy a week ago were completely wrecked in the strange debacle, due to a combination of circumstances, but accelerated into a crash by fear.

Under these circumstances of late tickers and spreads of 10, 20, and at times 30 points between the tape prices and those on the floor of the Exchange, the entire financial district was thrown into hopeless confusion and excitement. Wild-eyed speculators crowded the brokerage offices, awed by the disaster which had overtaken many of them. They followed the market literally "in the dark," getting but meager reports via the financial news tickers which printed the Exchange floor prices at ten-minute intervals.

Rumors, most of them wild and false, spread throughout the Wall Street district and thence throughout the country. One of the reports was that eleven speculators had committed suicide. A peaceful workman atop a Wall Street building looked down and saw a big crowd watching him, for the rumor had spread that he was going to jump off. Reports that the Chicago and Buffalo Exchanges had closed spread throughout the district, as did rumors that the New York Stock Exchange and the New York Curb Exchange were going to suspend trading. These rumors and reports were all found, on investigation, to be untrue.

(6) John D. Rockefeller, statement (29th October, 1929)

Believing that fundamental conditions of the country are sound and that there is nothing in the business situation to warrant the destruction of values that has taken place on the exchanges during the past week, my son and I have for some days been purchasing sound common stocks.

(7) New York Times (30th October, 1929)

Stock prices virtually collapsed yesterday, swept downward with gigantic losses in the most disastrous trading day in the stock market's history. Billions of dollars in open market values were wiped out as prices crumbled under the pressure of liquidation of securities which had to be sold at any price.

There was an impressive rally just at the close, which brought many leading stocks back from 4 to 14 points from their lowest points of the day.

Efforts to estimate yesterday's market losses in dollars are futile because of the vast number of securities quoted over the counter and on out-of-town exchanges on which no calculations are possible. However, it was estimated that 880 issues, on the New York Stock Exchange, lost between $8,000,000,000 and $9,000,000,000 yesterday. Added to that loss is to be reckoned the depreciation on issues on the Curb Market, in the over the counter market and on other exchanges.

Banking support, which would have been impressive and successful under ordinary circumstances, was swept violently aside, as block after block of stock, tremendous in proportions, deluged the market. Bid prices placed by bankers, industrial leaders and brokers trying to halt the decline were crashed through violently, their orders were filled, and quotations plunged downward in a day of disorganization, confusion and financial impotence.

Groups of men, with here and there a woman, stood about inverted glass bowls all over the city yesterday watching spools of ticker tape unwind and as the tenuous paper with its cryptic numerals grew longer at their feet their fortunes shrunk. Others sat stolidly on tilted chairs in the customers' rooms of brokerage houses and watched a motion picture of waning wealth as the day's quotations moved silently across a screen.

It was among such groups as these, feeling the pulse of a feverish financial world whose heart is the Stock Exchange, that drama and perhaps tragedy were to be found. The crowds about the ticker tape, like friends around the bedside of a stricken friend, reflected in their faces the story the tape was telling. There were no smiles. There were no tears either. Just the cameraderie of fellow-sufferers. Everybody wanted to tell his neighbor how much he had lost. Nobody wanted to listen. It was too repetitious a tale.

(8) Selected share prices from the The Wall Street Journal (1928-1929)

Company 3-3-1928

3-9-1928

3-9-1929

13-11-1929

$

$

$

$

Montgomery Ward 132

466

137

49

New York Central Railroad 160

256

256

160

Union Carbide & Carbon 145

413

137

59

American Telephone & Telegraph 77

181

304

197

Anaconda Copper 54

162

131

70

Westinghouse Electric Corporation 91

313

289

102

Electric Bond Holding Company 89

203

186

50

(9) Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday (1931)

The New York Times averages for fifty leading stocks had been almost cut in half, falling from a high of 311.90 in September to a low of 164.43 on November 13th; and the Times averages for twenty-five leading industrials had fared still worse, diving from 469.49 to 220.95. The Big Bull Market was dead. Billions of dollars' of profits - and paper profits - had disappeared. The grocer, the window-cleaner, and the seamstress had lost their capital. In every town there were families which had suddenly dropped from showy affluence into debt. Investors who had dreamed of retiring to live on their fortunes now found themselves back once more at the very beginning of the long road to riches. Day by day the newspapers printed the grim reports of suicides.

(10) Yip Harburg was interviewed by Studs Terkel in Hard Times (1970)

We thought American business was the Rock of Gibraltar. We were the prosperous nation, and nothing could stop us now. A brownstone house was forever. You gave it to your kids and they put marble fronts on it. There was a feeling of continuity. If you made it, it was there forever. Suddenly the big dream exploded. The impact was unbelievable.

I was walking along the street at that time, and you'd see the bread lines. The biggest one in New York City was owned by William Randolph Hearst. He had a big truck with several people on it, and big cauldrons of hot soup, bread. Fellows with burlap on their shoes were lined up all around Columbus Circle, and went for blocks and blocks around the park, waiting.

(11) M. A. Hamilton, In America Today (1932)

For years it has been an article of faith with the normal American that America, somehow, was different from the rest of the world. The smash of 1929 did not, of itself, shake this serene conviction. It looked, at the time, lust because it was so spectacular and catastrophic, like a shooting star disconnected with the fundamental facts. So the plain citizen, no matter how hard hit, believed. His dreams were shattered; but after all they had been only dreams; he could settle back to hard work and win out.

Then he found his daily facts reeling and swimming about him, in a nightmare of continuous disappointment. The bottom had fallen out of the market, for good. And that market had a horrid connection with his bread and butter, his automobile, and his installment purchases. Worst of all, unemployment became a hideous fact, and one that lacerated and tore at self-respect.

That is the trouble that lies at the back of the American mind. If America really is not "different," then its troubles, the same as those of Old Europe, will not be cured automatically. Something will have to be done - but what?

(12) New York Times (5th June, 1932)

Darwin's theory that man can adapt himself to almost any new environment is being illustrated, in this day of economic change, by thousands of New Yorkers who have discovered new ways to live and new ways to earn a living since their formerly placid lives were thrown into chaos by unemployment or kindred exigencies. Occupations and duties which once were scorned have suddenly attained unprecedented popularity

Two years ago citizens shied at jury duty. John Doe and Richard Roe summoned to serve on a jury, thought of all sorts of excuses. They called upon their ward leaders and their lawyers for aid in getting exemption, and when their efforts were rewarded they sighed with relief But now things are different.

The Hall of Jurors in the Criminal Courts Building is jammed and packed on court days. Absences of talesmen are infrequent. Why? Jurors get $4 for every day they serve.

Once the average New Yorker got his shine in an established bootblack parlor paying 10 cents, with a nickel tip. But now, in the Times Square and Grand Central zones, the sidewalks are lined with neophyte "shine boys," drawn from almost all walks of life. They charge a nickel and although a nickel tip is welcomed it is not expected.

In one block, on West Forty-third Street, a recent count showed nineteen shoe-shiners. They ranged in age from a 16-year-old, who should have been in school, to a man of more than 70, who said he had been employed in a fruit store until six months ago. Some sit quietly on their little wooden boxes and wait patiently for the infrequent customers. Others show true initiative and ballyhoo their trade, pointing accusingly at every pair of unshined shoes that passes.

Shining shoes, said one, is more profitable than selling apples - and he's tried them both.

"You see, when you get a shine kit it's a permanent investment," he said, "and it doesn't cost as much as a box of apples anyway."

According to the Police Department, there are approximately 7,000 of these "shine boys" making a living on New York streets at present. Three years ago they were so rare as to be almost non-existent, and were almost entirely boys under 17.

To the streets, too, has turned an army of new salesmen, peddling everything from large rubber balls to cheap neckties. Within the past two years the number of these hawkers has doubled. Fourteenth Street is still the Mecca of this type of salesmen; thirty-eight were recently counted between Sixth Avenue and Union Square and at one point there was a cluster of five.

Unemployment has brought back the newsboy in increasing numbers. He avoids the busy corners, where news stands are frequent, and hawks his papers in the side streets with surprising success. His best client is the man who is "too tired to walk down to the corner for a paper."

Selling Sunday papers has become a science. Youngsters have found that it is extremely profitable to invade apartment houses between 11 and 12 o'clock Sunday morning, knock on each apartment door, and offer the Sunday editions. Their profits are usually between $1.50 and $2.

(13) Edmund Wilson, New Republic (February, 1933)

There is not a garbage-dump in Chicago which is not diligently haunted by the hungry. Last summer the hot weather when the smell was sickening and the flies were thick, there were a hundred people a day coming to one of the dumps. A widow who used to do housework and laundry, but now had no work at all, fed herself and her fourteen year old son on garbage. Before she picked up the meat, she would always take off her glasses so that she couldn't see the maggots.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the United States in the 1920s (Answer Commentary)

Volstead Act and Prohibition (Answer Commentary)

The Ku Klux Klan (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject