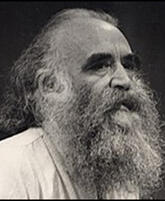

Igal Roodenko

Igal Roodenko, the son of Jewish immigrants from the Ukraine, was born on the 8th February, 1917. His father owned a small retail shop in New York City. Roodenko was raised as a Zionist and a socialist. He later recalled that at home he was taught "all the good values - humanist, anti-racist, anti-capitalist... the word socialist was a holy word to us."

Roodenko studied horticulture at Cornell University (1934-1938) with the intention of taking these skills to Palestine. He was radicalized at university and joined League for Industrial Democracy and the American Student Union. However, at university he became a pacifist and decided to stay in the United States: "aware of the conflict between my pacifism and my Zionism, and then ceased being a nationalist."

During the early stages of the Second World War Roodenko organized anti-war demonstrations. As Anne Yoder has pointed out: "Roodenko... circulated petitions, and wrote letters to Congressmen and newspaper editors urging their support of world peace. Roodenko's arguments were already incisive, showing the ability to cut through rhetoric to the root of a problem, and presented in a powerful style that not only highlighted his firm commitment to his beliefs but his ability to move others to action."

In 1942 he registered his conscientious objection to war and refused to accept being drafted into the military. In July 1943, he joined the Bureau of Land Reclamation of the Department of the Interior. Along with other pacifists he helped to erect an earth dam at the head of the Mancos River to irrigate Mancos Valley.

On 29th September, 1943, six war objectors imprisoned at Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, started a hunger strike against censorship of mail and reading material by prison authorities. The following month Roodenko began his own hunger and work strike in support of these men: "My concern was with... censorship which occasionally reached preposterous depths of pettiness and stupidity, censorship of mail and reading matter which frequently denied men the opportunity of reading and writing about those very matters which made them sacrifice comforts and respect for the ignominy and disrepute of a prison record."

Roodenko was arrested for his refusal to work and on 6th June, 1944 a Denver judge found Roodenko guilty and sentenced him to three years in a federal penitentiary. He was released from Sandstone Federal Correctional Institution in Minnesota in December 1946.

On his release he joined the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE). In early 1947, CORE announced plans to send eight white and eight black men into the Deep South to test the Supreme Court ruling that declared segregation in interstate travel unconstitutional. organized by George Houser and Bayard Rustin, the Journey of Reconciliation was to be a two week pilgrimage through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Kentucky.

Although Walter White of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) was against this kind of direct action, he volunteered the service of its southern attorneys during the campaign. Thurgood Marshall, head of the NAACP's legal department, was strongly against the Journey of Reconciliation and warned that a "disobedience movement on the part of Negroes and their white allies, if employed in the South, would result in wholesale slaughter with no good achieved."

The Journey of Reconciliation began on 9th April, 1947. The team included Igal Roodenko, George Houser, Bayard Rustin, James Peck, Joseph Felmet, Nathan Wright, Conrad Lynn, Wallace Nelson, Andrew Johnson, Eugene Stanley, Dennis Banks, William Worthy, Louis Adams, Worth Randle and Homer Jack.

Wallace Nelson, Ernest Bromley, James Peck, Igal Roodenko, Bayard Rustin,

Joseph Felmet, George Houser and Andrew Johnson.

James Peck was arrested with Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson in Durham. After being released he was arrested once again in Asheville and charged with breaking local Jim Crow laws. In Chapel Hill five members of the team was dragged off the bus and physically assaulted before being taken into custody by the local police.

Members of the Journey of Reconciliation team were arrested several times. In North Carolina, two of the African Americans, Bayard Rustin and Andrew Johnson, were found guilty of violating the state's Jim Crow bus statute and were sentenced to thirty days on a chain gang. However, Judge Henry Whitfield made it clear he found that behaviour of the white men even more objectionable. He told Igal Roodenko and Joseph Felmet: "It's about time you Jews from New York learned that you can't come down her bringing your N******* with you to upset the customs of the South. Just to teach you a lesson, I gave your black boys thirty days, and I give you ninety."

The Journey of Reconciliation achieved a great deal of publicity and was the start of a long campaign of direct action by the Congress of Racial Equality. In February 1948 the Council Against Intolerance in America gave George Houser and Bayard Rustin the Thomas Jefferson Award for the Advancement of Democracy for their attempts to bring an end to segregation in interstate travel.

Roodenko was an active member of the War Resisters League (WRL) and was a member of its Executive Committee for thirty years. During the Vietnam War he was arrested ten times while taking part in anti-war protests. In 1970 he became a full-time worker for WRL. He was also active in Men of All Colors Together, a gay men's group working against racism within the gay community.

Igal Roodenko died of a heart attack on 28th April, 1991.

Primary Sources

(1) Instructions produced by George Houser and Bayard Rustin for the Journey of Reconciliation (April, 1947)

If you are a Negro, sit in a front seat. If you are white, sit in a rear seat.

If the driver asks you to move, tell him calmly and courteously: "As an interstate passenger I have a right to sit anywhere in this bus. This is the law as laid down by the United States Supreme Court".

If the driver summons the police and repeats his order in their presence, tell him exactly what you said when he first asked you to move.

If the police asks you to "come along," without putting you under arrest, tell them you will not go until you are put under arrest.

If the police put you under arrest, go with them peacefully. At the police station, phone the nearest headquarters of the NAACP, or one of your lawyers. They will assist you.