European Recruits in the American Civil War

Rhode Island abolished slavery in 1774. It was followed by Vermont (1777), Pennsylvania (1780), Massachusetts (1781), New Hampshire (1783), Connecticut (1784), New York (1799) and New Jersey (1804). The new states of Maine, Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, Indiana, Kansas, Oregon, California and Illinois also did not have slaves. The importation of slaves from other countries was banned in 1808. However, the selling of slaves within the southern states continued.

Conflict grew between the northern and southern states over the issue of slavery. The northern states were going through an industrial revolution and desperately needed more people to work in its factories. Industrialists in the North believed that, if freed, the slaves would leave the South and provide the labour they needed. The North also wanted tariffs on imported foreign goods to protect their new industries. The South was still mainly agricultural and purchased a lot of goods from abroad and was therefore against import tariffs.

The vast majority of European immigrants that arrived at the beginning of the 19th century opposed slavery. Leaders of immigrant organizations such as Carl Schurz (Germany),Tufve Nilsson Hasselquist (Sweden) and Hans Christian Heg (Norway) became involved in the struggle for abolition.

Abraham Lincoln, a northern opponent of slavery, was elected as president in 1861. It has been pointed out that without the support of an overwhelming number of immigrants, Lincoln would have lost the election. After Lincoln became president eleven southern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia) decided to leave the Union and form their own separate government in the South.

This resulted in the outbreak of the American Civil War. European immigrants joined the Union Army in large numbers. Over 6,000 Germans in New York immediately responded to Lincoln's call for volunteers. Another 4,000 Germans in Pennsylvania also joined. The French community were keen to show its support of the Union. The Lafayette Guards, an entirely French company, was led by Colonel Regis de Trobriand. The 55th New York Volunteers was also mainly composed of Frenchmen.

It is estimated that over 400,000 immigrants served with the Union Army. This included 216,000 Germans and 170,000 Irish soldiers. There were several important German born military leaders such as August Willich, Carl Schurz, Alexander Schimmelfennig, Peter Osterhaus, Franz Sigel and Max Weber. One Irish immigrant, Thomas Meagher, became a highly successful commander in the war. Another important military figure was the Norwegian soldier, Hans Christian Heg, who was mainly responsible for establishing the Fifteenth Wisconsin Volunteers (also known as the Scandinavian Regiment).

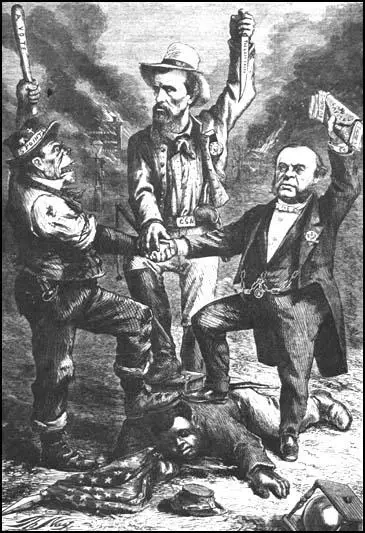

Weekly suggesting that the Irish were joining with Southern slaveholders and New York capitalists to deny African Americans their freedom.

An estimated 4,000 Swedes fought in the Union Army. Hans Mattson had a successful career as a colonel in the Union Army and later became Secretary of State for Minnesota (1870-1872).

At Chickamauga 63% of the Scandinavian Regiment were killed, wounded or captured. This included Colonel Hans Christian Heg, the highest ranking officer in Wisconsin to die in the war. Heavy losses were also experienced by the Scandinavian Regiment at Pickett's Mill (27th May, 1864).

The Confederate Army had few foreign-born soldiers. There main support came from Irish immigrants and an estimated 40,000 joined the forces fighting the Union Army. The Irish tended to support the Democratic Party rather than the Republican Party. This led to the Irish taking part in draft riots in Boston and New York City during the summer of 1863.

The Irish had little sympathy for slaves as they feared that if they were given their freedom they would move north and threaten the jobs being done by Irish immigrants. One leading Irish-American politician, John Mitchel, wrote in his newspaper, The Citizen in 1856: "He would be a bad Irishman who voted for principles which jeopardized the present freedom of a nation of white men, for the vague forlorn hope of elevating blacks to a level for which it is at least problematical whether God and nature ever intended them."

Primary Sources

(1) John Mitchel, The Citizen (1856)

He would be a bad Irishman who voted for principles which jeopardized the present freedom of a nation of white men, for the vague forlorn hope of elevating blacks to a level for which it is at least problematical whether God and nature ever intended them.

(2) Samuel Gompers and his family emigrated to the United States in the summer of 1863.

It became harder and harder to get along as our family increased and expenses grew. London seemed to offer no response to our efforts towards betterment. About this time we began to hear more and more about the United States. The great struggle against human slavery which was convulsing America was of vital interest to wage-earners who were everywhere struggling for industrial opportunity and freedom. My work in the cigar factory gave me a chance to hear the men discuss this issue. Youngster that I was, I was absorbed in listening to this talk and made my little contribution by singing with all the feeling in my little heart the popular songs, "The Slave Ship" and "To the West, To the West, To the Land of the Free".

The sympathy of English wage-earners was with the cause of the Union which was bound up with the anti-slavery struggle. We heard the story from the Abolitionists. This was true of all the workers of Great Britain even though their own industrial welfare was menaced as was that of the textile workers who were dependent upon cotton shipped from our southern ports. Even against their own economic interests the British textile workers were opposed to the Palmerston diplomatic policy of recognition for the Confederacy and the plan of the British and French governments to raise the blockage of the cotton ports.

The Cigarmakers' Society Union of England, whose members were frequently unemployed and suffering, established an emigration fund - that is, instead of paying the members unemployment benefits, a sum of money was granted to help passage from England to the United States. The sum was not large, between five and ten pounds. This was a very practical method which benefited both the emigrants and those who remained by decreasing the number seeking work in their trade. After much discussion and consultation father decided to go to the New World. He had friends in New York City and a brother-in-law who proceeded us by six months to whom father wrote we were coming.

There came busy days in which my mother gathered together and packed our household belongings. Father secured passage on the City of London, a sailing vessel which left Chadwick Basin, June 10, 1863, and reached Castle Garden, July 29, 1863, after seven weeks and one day.

Our ship was the old type of sailing vessel. We had none of the modern comforts of travel. The sleeping quarters were cramped and we had to had to do our own cooking in the gallery of the boat. Mother had provided salt beef and other preserved meats and fish, dried vegetables, and red pickled cabbage which I remember most vividly. We were all seasick except father, mother the longest of all. Father had to do all the cooking in the meanwhile and take care of the sick. There was a Negro man employed on the boat who was very kind in many ways to help father. Father did not know much about cooking.

When we reached New York we landed at the old Castle Garden of lower Manhattan, now the Aquarium, where we were met by relatives and friends. As we were standing in a little group, the Negro who had befriended father on the trip, came off the boat. Father was grateful and as a matter of courtesy, shook hands with him and gave him his blessing. Now it happened that the draft and negro rights were convulsing New York City. Only that very day Negroes had been chased and hanged by mobs. The onlookers, not understanding, grew very much excited over father's shaking hands with this Negro. A crowd gathered round and threatened to hang both father and the Negro to the lamp-post.

(3) An anonymous letter from a Norwegian immigrant in Dodge County, Minnesota, appeared in Morgenbladet, a newspaper in Norway on 22nd November, 1862.

At this time life is not very pleasant in this so-called wonderful America. The country is full of danger, and at no time do we feel any security for our lives or property. Next month (October) there is to be a levy of soldiers for military service, and our county alone is to supply 118 men, in addition to those who have already enlisted as volunteers.

Last week we, therefore, all had to leave our harvesting work and our weeping wives and children and appear at the place of enlistment, downcast and worried. We waited until 6 o'clock in the afternoon. Then, finally, the commissioner arrived, accompanied by a band, which continued playing for a long time to encourage us and give us a foretaste of the joys of war. But we thought only of its sorrows, and despite our reluctance, had to give our name and age. To tempt people to enlist as volunteers, everybody who would volunteer was offered $225, out of which $125 is paid by the county and $100 by the state.

Several men then enlisted, Yankees and Norwegians; and we others, who preferred to stay at home and work for our wives and children, were ordered to be ready at the next levy. Then who is to go will be decided by drawing lots. In the meantime, we were forbidden to leave the country without special permission, and we were also told that no one would get a passport to leave the country. Dejected, we went home, and now we are in a mood of uncertainty and tension, almost like prisoners of war in the formerly do free country. Our names have been taken down - perhaps I shall be a soldier next month and have to leave my home, my wife, child, and everything I have been working for over so many years.

But this is not the worst of it. We have another and far more cruel enemy nearby, namely, the Indians. They are raging, especially in northwestern Minnesota, and perpetrate cruelties which no pen can describe. Every day, settlers come through here who have had to abandon everything they owned to escape a most painful death. Several Norwegians have been killed and many women have been captured.

From this you may see how we live: on the one hand, the prospect of being carried off as cannon fodder to the South; on the other, the imminent danger of falling prey to the Indians; add to this the heavy war tax and everybody has to pay whether he is enlisted as a soldier or not. You are better off who can live at home in peaceful Norway. God grant us patience and fortitude to bear these heavy burdens.

(4) Carl Schurz, Autobiography of Carl Schurz (1906)

Abraham Lincoln appointed General Franz Sigel as the commander of the First Army Corps of the Army of Virginia. The German-American troops welcomed Sigel with great enthusiasm, which the rank and file of the native American regiments at least seemed to share. He brought a splendid military reputation with him. He had bravely fought for liberty in Germany, and conducted there the last operations of the revolutionary army in 1849. He had been one of the foremost to organize and lead that force of armed men, mostly Germans, that seemed suddenly to spring out of the pavements of St. Louis, and whose prompt action saved that city and the State of Missouri to the Union. On various fields, especially at Pea Ridge, he had distinguished himself by personal gallantry as well as by skillful leadership.

(5) John Peter Altgeld, Forum Magazine (February, 1890)

The question whether immigration shall be encouraged or restricted, and whether naturalization shall be made more difficult or not, must be considered both from the political and from an industrial point of view; and in each case it is necessary to glance back and see what have been the character, the conduct, and the political leaning of the immigrant, and what he has done to develop and enrich our country.

If we look at the political side first, and, as our space is limited, we will go back to 1860, calling attention, however, to the fact that up to that time, no matter from what cause, the immigration had been almost entirely to the Northern and free States, and not to the slave States. These, when carefully examined in connection with election returns, will show that but for the assistance of the immigrant the election of Abraham Lincoln as president of the United States would have been an impossibility, and the nineteenth century would never have seen the great free republic we see, and the shadow of millions of slaves would today darken and curse the continent.

The Scandinavians have always, nearly to a man, voted the Republican ticket. The Germans, likewise, were nearly always Republicans. In fact, the States having either a large Scandinavian or a large German population have been distinguished as the banner Republican States. Notably is this true of Iowa, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan, which has a large Scandinavian population; and of Illinois, Ohio and Pennsylvania, which have a very large German population.