Stokely Carmichael

Stokely Carmichael was born in the Port of Spain, Trinidad, on 29th June, 1941. Carmichael moved to the United States in 1952 and attended high school in New York City. He entered Howard University in 1960 and soon afterwards joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

In 1961 Carmichael became a member of the Freedom Riders. After training in non-violent techniques, black and white volunteers sat next to each other as they travelled through the Deep South. Local police were unwilling to protect these passengers and in several places they were beaten up by white mobs. In Jackson, Mississippi, Carmichael was arrested and jailed for 49 days in Parchman Penitentiary. Carmichael also worked on the Freedom Summer project and in 1966 became chairman of SNCC.

On 5th June, 1966, James Meredith started a solitary March Against Fear from Memphis to Jackson, to protest against racism. Soon after starting his march he was shot by sniper. When they heard the news, other civil rights campaigners, including Carmichael, Martin Luther King and Floyd McKissick, decided to continue the march in Meredith's name.

When the marchers got to Greenwood, Mississippi, Carmichael and some of the other marchers were arrested by the police. It was the 27th time that Carmichael had been arrested and on his release on 16th June, he made his famous Black Power speech. Carmichael called for "black people in this country to unite, to recognize their heritage, and to build a sense of community". He also advocated that African Americans should form and lead their own organizations and urged a complete rejection of the values of American society.

The following year Carmichael joined with Charles V. Hamilton to write the book, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America (1967). Some leaders of civil rights groups such as the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) and Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), rejected Carmichael's ideas and accused him of black racism.

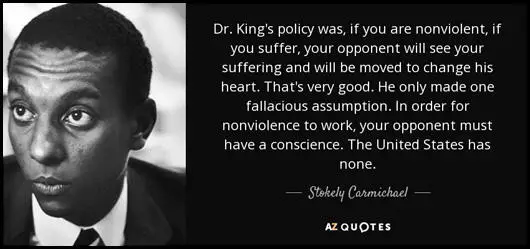

Carmichael also adopted the slogan of "Black is Beautiful" and advocated a mood of black pride and a rejection of white values of style and appearance. This included adopting Afro hairstyles and African forms of dress. Carmichael began to criticize Martin Luther King and his ideology of nonviolence. He eventually joined the Black Panther Party where he became "honorary prime minister".

When Carmichael denounced United States involvement in the Vietnam War, his passport was confiscated and held for ten months. When his passport was returned, he moved with his wife, Miriam Makeba, to Guinea, where he wrote the book, Stokely Speaks: Black Power Back to Pan-Africanism (1971).

Carmichael, who adopted the name, Kwame Ture, also helped to establish the All-African People's Revolutionary Party and worked as an aide to Guinea's prime minister, Sekou Toure. After the death of Toure in 1984 Carmichael was arrested by the new military regime and charged with trying to overthrow the government. However, he only spent three days in prison before being released.

Stokely Carmichael died of cancer on 15th November, 1998.

Primary Sources

(1) Stokely Carmichael, interviewed by Gordon Parks, Life Magazine (1967)

When I first heard about the Negroes sitting in at lunch counters down South, I thought they were just a bunch of publicity hounds. But one night when I saw those young kids on TV, getting back up on the lunch counter stools after being knocked off them, sugar in their eyes, ketchup in their hair -- well, something happened to me. Suddenly I was burning.

(2) Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America (1966)

One of the tragedies of the struggle against racism is that up to this point there has been no national organization which could speak to the growing militancy of young black people in the urban ghettos and the black-belt South. There has been only a "civil rights" movement, whose tone of voice was adapted to an audience of middle-class whites. It served as a sort of buffer zone between that audience and angry young blacks. It claimed to speak for the needs of a community, but it did not speak in the tone of that community. None of its so-called leaders could go into a rioting community and be listened to. In a sense, the blame must be shared-along with the mass media-by those leaders for what happened in Watts, Harlem, Chicago, Cleveland, and other places. Each time the black people in those cities saw Dr. Martin Luther King get slapped they became angry. When they saw little black girls bombed to death in a church and civil rights workers ambushed and murdered, they were angrier; and when nothing happened, they were steaming mad. We had nothing to offer that they could see, except to go out and be beaten again.

We had only the old language of love and suffering. And in most places-that is, from the liberals and middle class-we got back the old language of patience and progress. Such language, along with admonitions to remain non-violent and fear the white backlash, convinced some that that course was the only course to follow. It misled some into believing that a black minority could bow its head and get whipped into a meaningful position of power. The very notion is absurd.

(3) Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America (1966)

According to its advocates, social justice will be accomplished by "integrating the Negro into the mainstream institutions of the society from which he has been traditionally excluded." This concept is based on the assumption that there is nothing of value in the black community and that little of value could be created among black people. The thing to do is to siphon off the "acceptable" black people into the surrounding middle-class white community. The goals of integrationists are middle-class goals, articulated primarily by a small group of Negroes with middle-class aspirations or status.

There is no black man in the country who can live "simply as a man." His blackness is an everpresent fact of this racist society, whether he recognizes it or not. It is unlikely that this or the next generation will witness the time when race will no longer be relevant in the conduct of public affairs and in public policy decision-making.

"Integration" as a goal today speaks to the problem of blackness not only in an unrealistic way but also in a despicable way. It is based on complete acceptance of the fact that in order to have a decent house or education, black people must move into a white neighborhood or send their children to a white school. This reinforces, among both black and white, the idea that "white" is automatically superior and "black" is by definition inferior. For this reason, "integration" is a subterfuge for the maintenance of white supremacy.

(4) Cleveland Sellers was a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. His autobiography, The River of No Return, was published in 1973.

We had our first major trouble with the police on June 17, in Greenwood. It began when a contingent of state troopers arbitrarily decided that we could not put up our sleeping tent on the grounds of a black high school. When Stokely attempted to put the tent up anyway, he was arrested. Within minutes, word of his arrest had spread all over town. The rally that night, which was held in a city park, attracted almost three thousand people - five times the usual number.

Stokely, who'd been released from jail just minutes before the rally began, was the last speaker. He was preceded by McKissick, Dr. King and Willie Ricks. Like the rest of us, they were angry about Stokely's unnecessary arrest. Their speeches were particularly militant. When Stokely moved forward to speak, the crowd greeted him with a huge roar. He acknowledged his reception with a raised arm and clenched fist.

Realizing that he was in his element, with his people, Stokely let it all hang out. "This is the twenty-seventh time I have been arrested - and I ain't going to jail no more!" The crowd exploded into cheers and clapping.

"The only way we gonna stop them white men from whuppin' us is to take over. We been saying freedom for six years and we ain't got nothin'. What we gonna start saying now is Black Power!"

The crowd was right with him. They picked up his thoughts immediately.

"BLACK POWER!" they roared in unison.

(5) Stokely Carmichael, New York Review of Books (22nd September, 1966)

One of the tragedies of the struggle against racism is that up to now there has been no national organization which could speak to the growing militancy of young black people in the urban ghetto. There has been only a civil rights movement, whose tone of voice was adapted to an audience of liberal whites. It served as a sort of buffer zone between them and angry young blacks. None of its so-called leaders could go into a rioting community and be listened to. In a sense, I blame ourselves - together with the mass media - for what has happened in Watts, Harlem, Chicago, Cleveland, Omaha. Each time the people in those cities saw Martin Luther King get slapped, they became angry; when they saw four little black girls bombed to death, they were angrier; and when nothing happened, they were steaming. We had nothing to offer that they could see, except to go out and be beaten again. We helped to build their frustration.

An organization which claims to be working for the needs of a community - as SNCC does - must work to provide that community with a position of strength from which to make its voice heard. This is the significance of black power beyond the slogan.

Black power can be clearly defined for those who do not attach the fears of white America to their questions about it. We should begin with the basic fact that black Americans have two problems: they are poor and they are black. All other problems arise from this two-sided reality: lack of education, the so-called apathy of black men. Any program to end racism must address itself to that double reality.

(6) New York Times (16th November, 1998)

Kwame Ture, the flamboyant civil rights leader known to most Americans as Stokely Carmichael, died Sunday in Conakry, Guinea. He was 57 and is best remembered for his use of the phrase "black power," which in the mid-1960's ignited a white backlash and alarmed an older generation of civil rights leaders, including the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Ture, who changed his name in 1978 to honor Kwame Nkrumah and Ahmed Sekou Toure, two African socialist leaders who had befriended him, spent most of the last 30 years in Guinea, calling himself a revolutionary and advocating a Pan-African ideology that evoked few resonances in the United States, or, for that matter, Africa.

Ture's advocacy of Pan-Africanism was the last phase in a political evolution that passed from indifference to the civil rights movement when he was a high school student to emergence as an effective nonviolent volunteer risking his life against segregation to honorary prime minister of the Black Panther Party.

Stokely Carmichael was inspired to participate in the civil rights movement by the bravery of those blacks and whites who protested segregated service with sit-ins at lunch counters in the South.

Rejecting scholarships from several white universities, he entered Howard University in Washington in 1960. By the end of his freshman year, he had joined the Freedom Rides of the Congress of Racial Equality, hazardous bus trips of blacks and whites that challenged segregated interstate travel in the South. The Freedom Riders often met with violence, and at their destinations Carmichael and the others were arrested and jailed, the first incarcerations he experienced. One early arrest brought him a particularly harsh 49-day sentence in Parchman Penitentiary in Mississippi.

The young Carmichael was radicalized by his experiences working in the segregated South, where peaceful protesters were beaten, brutalized and sometimes killed for seeking the ordinary rights of citizens. He once recalled watching from his hotel room in a little Alabama town while nonviolent black demonstrators were beaten and shocked with cattle prods by the police.

Carmichael was arrested so often as a nonviolent volunteer that he lost count after 32. His growing impatience with the tactics of passive resistance was gaining support, and in 1966 he was chosen as chairman of SNCC, replacing John Lewis, a hardworking integrationist who is now a Congressman from Georgia.

Barely a month after his selection, Carmichael, then just 25, raised the call for black power, thereby signaling a crossroads in the civil rights struggle. Increasingly uncomfortable with Dr. King's resolute nonviolence, he sensed a shift among some younger blacks in the direction of black separatism. Many were listening sympathetically to the urgings of Malcolm X, who had been assassinated a year and a half earlier, that the struggle should be carried out by any means necessary.

It was June 16, 1966, and Carmichael, a spellbinding orator, was addressing a crowd of 3,000 in a park in Greenwood, Mississippi. James Meredith, who had integrated the University of Mississippi, was wounded on his solitary "Walk Against Fear" from Memphis to Jackson, and volunteers were marching in his place. When they set up camp in Greenwood, Carmichael was arrested and his frustration was obvious.

"This is the 27th time," he said in disgust after his release. "We been saying 'Freedom' for six years," he continued, referring to the chant that movement protesters used as they stood up to racist politicians and hostile policemen pointing water hoses and unleashing snarling dogs. "What we are going to start saying now is 'Black Power!' "

The crowd quickly took up the phrase. "Black Power!" it repeated in a cry that would soon be echoed in communities from Oakland to Newark. But if Carmichael's call for black power galvanized many young blacks, it troubled others, who thought it sounded anti-white, provocative and violent. And it struck fear into many whites.

(7) C. L. R. James, speech on Black Power in London in 1967.

Black Power. I believe that this slogan is destined to become one of the great political slogans of our time. Of course, only time itself can tell that. Nevertheless, when we see how powerful an impact this slogan has made it is obvious that it touches very sensitive nerves in the political consciousness of the world today. This evening I do not intend to tell you that it is your political duty to fight against racial consciousness in the British people; or that you must seek ways and means to expose and put an end to the racialist policies of the present Labour government. If you are not doing that already I don't see that this meeting will help you to greater political activity. That is not the particular purpose of this meeting though, as you shall hear, there will be specific aims and concrete proposals. What I aim to do this evening is to make clear to all of us what this slogan Black Power means, what it does not mean, cannot mean; and I say quite plainly, we must get rid, once and for all, of a vast amount of confusion which is arising, copiously, both from the right and also from the left. Now I shall tell you quite precisely what I intend to do this evening. The subject is extremely wide, comprising hundreds of millions of people, and therefore in the course of an address of about an hour or so, we had better begin by being very precise about what is going to be said and what is not going to be said.

But before I outline, so to speak, the premises on which I will build, I want to say a few words about Stokely Carmichael: I think I ought to say Stokely because everybody, everywhere, calls him Stokely which I think is a political fact of some importance. The slogan Black Power, beginning in the United States and spreading from there elsewhere, is undoubtedly closely associated with him and with those who are fighting with him. But for us in Britain his name, whether we like it or not, means more than that. It is undoubtedly his presence here, and the impact that he has made in his speeches and his conversations, that have made the slogan Black Power reverberate in the way that it is doing in political Britain - and even outside of that, in Britain in general. And I want to begin by making a particular reference to Stokely which, fortunately, I am in a position to make. And I do this because on the whole in public speaking, in writing (and also to a large degree in private conversation), I usually avoid, take great care to avoid placing any emphasis on a personality in politics.

I was reading the other day Professor Levi-Strauss and in a very sharp attack on historical conceptions prevalent today, I saw him say that the description of personality, or of the anecdote (which so many people of my acquaintance historically and politically live by) were the lowest forms of history. With much satisfaction I agreed; I have been saying so for nearly half a century. But then he went on to place the political personality within a context that I thought was misleading, and it seemed to me that in avoiding it as much as I have done, I was making a mistake, if not so much in writing, certainly in public speech. And that is why I begin what I have to say, and will spend a certain amount of time, on one of the most remarkable personalities of contemporary politics. And I am happy to say that I did not have to wait until Stokely came here to understand the force which he symbolizes.

I heard him speak in Canada at Sir George Williams University in March of this year. There were about one thousand people present, chiefly white students, about sixty or seventy Negro people, and I was so struck by what he was saying and the way he was saying it (a thing which does not happen to me politically very often) that I sat down immediately and took the unusual step of writing a letter to him, a political letter. After all, he was a young man of twenty-three or twenty-four and I was old enough to be his grandfather and, as I say, I thought I had a few things to tell him which would be of use to him and, through him, the movement he represented.