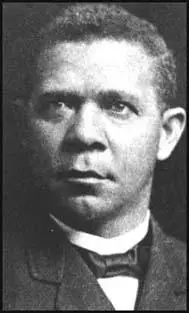

Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro was born a mulatto slave in Franklin Country on 5th April, 1856. His father was an unknown white man and his mother, the slave of James Burroughs, a small farmer in Virginia. Later, his mother married the slave, Washington Ferguson. When Booker entered school he took the name of his stepfather and became known as Booker T. Washington.

After the Civil War the family moved to Malden, West Virginia. Ferguson worked in the salt mines and at the age of nine Booker found employment as a salt-packer. A year later he became a coal miner (1866-68) before going to work as a houseboy for the wife of Lewis Ruffner, the owner of the mines. She encouraged Booker to continue his education and in 1872 he entered the Hampton Agricultural Institute.

The principal of the institute was Samuel Armstrong, an opponent of slavery who had been commander of African American troops during the Civil War. Armstrong believed that it was important that the freed slaves received a practical education. Armstrong was impressed with Washington and arranged for his tuition to be paid for by a wealthy white man.

Armstrong became Washington's mentor. Washington described Armstrong in his autobiography as "a great man - the noblest rarest human being it has ever been my privilege to meet". Armstrong's views of the development of character and morality and the importance of providing African Americans with a practical education had a lasting impact on Washington's own philosophy.

After graduating from the Hampton Agricultural Institute in 1875 Washington returned to Malden and found work with a local school. After a spell as a student at Wayland Seminary in 1878 he was employed by Samuel Armstrong to teach in a program for Native Americans.

In 1880, Lewis Adams, a black political leader in Macon County, agreed to help two white Democratic Party candidates, William Foster and Arthur Brooks, to win a local election in return for the building of a Negro school in the area. Both men were elected and they then used their influence to secure approval for the building of the Tuskegee Institute.

Samuel Armstrong, principal of the successful Hampton Agricultural Institute, was asked to recommend a white teacher to take charge of this school. However, he suggested that it would be a good idea to employ Washington instead.

The Tuskegee Negro Normal Institute was opened on the 4th July, 1888. The school was originally a shanty building owned by the local church. The school only received funding of $2,000 a year and this was only enough to pay the staff. Eventually Washington was able to borrow money from the treasurer of the Hampton Agricultural Institute to purchase an abandoned plantation on the outskirts of Tuskegee and built his own school.

The school taught academic subjects but emphasized a practical education. This included farming, carpentry, brickmaking, shoemaking, printing and cabinetmaking. This enabled students to become involved in the building of a new school. Students worked long-hours, arising at five in the morning and finishing at nine-thirty at night.

By 1888 the school owned 540 acres of land and had over 400 students. Washington was able to attract good teachers to his school such as Olivia Davidson , who was appointed assistant principal, and Adella Logan. Washington's conservative leadership of the school made it acceptable to the white-controlled Macon County. He did not believe that blacks should campaign for the vote, and claimed that blacks needed to prove their loyalty to the United States by working hard without complaint before being granted their political rights.

Southern whites, who had previously been against the education of African Americans, supported Washington's ideas as they saw them as means of encouraging them to accept their inferior economic and social status. This resulted in white businessmen such as Andrew Carnegie and Collis Huntington donating large sums of money to his school.

In September, 1895, Washington became a national figure when his speech at the opening of the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta was widely reported by the country's newspapers. Washington's conservative views made him popular with white politicians who were keen that he should become the new leader of the African American population. To help him in this President William McKinley visited the Tuskegee Institute and praised Washington's achievements.

In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Washington to visit him in the White House. To southern whites this was going too far. One editor wrote: "With our long-matured views on the subject of social intercourse between blacks and whites, the least we can say now is that we deplore the President's taste, and we distrust his wisdom."

Washington now spent most of his time on the lecture circuit. His African American critics who objected to the way Washington argued that it was the role of blacks to serve whites, and that those black leaders who demanded social equality were political extremists.

In 1900 Washington helped establish the National Negro Business League. Washington, who served as president, ensured that the organization concentrated on commercial issues and paid no attention to questions of African American civil rights. To Washington, the opportunity to earn a living and acquire property was more important than the right to vote. Like those who helped fund the Tuskegee Institute, Washington was highly critical of the emerging trade union movement in the United States.

Washington worked closely with Thomas Fortune, the owner of The New York Age. He regularly supplied Fortune with news stories and editorials favourable to himself. When the newspaper got into financial difficulties, Washington became secretly one of its principal stockholders.

Washington's autobiography was published in The Outlook magazine and was eventually published as Up From Slavery in 1901. His critics argued that the views expressed in his books, articles and lectures were essentially the prevailing views of white Americans.

In 1903 William Du Bois joined the attack on Washington with his essay on his work in The Soul of Black Folks. Washington retaliated with criticisms of Du Bois and his Niagara Movement. The two men also clashed over the establishment of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in 1909.

The following year, William Du Bois and twenty-two other prominent African Americans signed a statement claiming: "We are compelled to point out that Mr. Washington's large financial responsibilities have made him dependent on the rich charitable public and that, for this reason, he has for years been compelled to tell, not the whole truth, but that part of it which certain powerful interests in America wish to appear as the whole truth."

Although he now had a large number of critics, Washington continued to be consulted by powerful white politicians and had a say in the African American appointments made by Theodore Roosevelt (1901-09) and William H. Taft (1909-13).

Booker Taliaferro Washington was taken ill and entered St. Luke's Hospital, New York City, on 5th November, 1915. Suffering from arteriosclerosis he was warned that he did not have long to live. He decided to travel to Tuskegee where he died on 14th November. Over 8,000 people attended his funeral held in the Tuskegee Institute Chapel.

Primary Sources

(1) Booker T. Washington, The Educational Outlook of the South (1884)

Any movement for the elevation of the Southern Negro in order to be successful, must have to a certain extent the cooperation of the Southern whites. They control government and own the property - whatever benefits the black man benefits the white man. The proper education of all the whites will benefit the Negro as much as the education of the Negro will benefit the whites.

I repeat for emphasis that any work looking towards the permanent improvement of the Negro South, must have for one of its aims the fitting of him to live friendly and peaceably with his white neighbors both socially and politically. In spite of all talk of exodus, the Negro's home is permanently in the South; for coming in the bread-and-meat side of the question, the white man needs the Negro, and the Negro needs the white man. His home being permanently in the South, it is our duty to help him prepare himself to live there an independent, educated citizen.

(2) Booker T. Washington, Up from Slavery: An Autobiography (1901)

I believe it is the duty of the Negro - as the greater part of the race is already doing - to deport himself modestly in regard of political claims, depending upon the slow but sure influences that proceed from the possessions of property, intelligence, and high character for the full recognition of his political rights. I think that the according of the full exercise of political rights is going to be a matter of natural, slow growth, not an overnight gourdvine affair.

As a rule I believe in universal, free suffrage, but I believe that in the South we are confronted with peculiar conditions that justify the protection of the ballot in many of the states, for a while at least, either by an educational test, a property test, or by both combined; but whatever tests are required, they should be made to apply with equal and exact justice to both races.

(3) William Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folks (1903)

Easily the most striking thing in the history of the American Negro since 1876 is the ascendancy of Mr. Booker T. Washington. It began at the time when war memories and ideals were rapidly passing; a day of astonishing commercial development was dawning; a sense of doubt and hesitation overtook the freedmen's sons - then it was his leading began. His program of industrial education, conciliation of the South, and submission and silence as to civil and political rights, was not wholly original; the Free Negroes from 1830 up to wartime had striven to build industrial schools, and the American Missionary Association had from the first taught various trades. But Mr. Washington first indissolubly linked these things; he put enthusiasm, unlimited energy, and perfect faith into this program, and changed it from a bypath into a veritable Way of Life.

(4) Booker T. Washington, The Future of the American Negro (1899)

I see no way out of the Negro's condition in the South by returning to Africa. Aside from other insurmountable obstacles, there is no place in Africa for him to go where his condition would be improved. All Europe - especially England, France and Germany - has been running a mad race for the last twenty years, to see which could gobble up the greater part of Africa; and there is practically nothing left. In a talk with Henry M. Stanley, the explorer, he told me that he knew no place in Africa where the Negroes of the United States might go to advantage.

(5) Statement on Booker T. Washington signed by William Du Bois and twenty-two other African Americans (26th October, 1910)

The undersigned Negro-Americans have heard, with great regret, the recent attempt to assure England and Europe that their condition in America is satisfactory. They sincerely wish that such were the case, but it becomes their plan duty to say that Mr. Booker T. Washington, or any other person, is giving the impression abroad that the Negro problem in America is in process of satisfactory solution, he is giving an impression which is not true.

We say this without personal bitterness toward Mr. Washington. He is a distinguished American and has a perfect right to his opinions. But we are compelled to point out that Mr. Washington's large financial responsibilities have made him dependent on the rich charitable public and that, for this reason, he has for years been compelled to tell, not the whole truth, but that part of it which certain powerful interests in America wish to appear as the whole truth.

Today in eight states where the bulk of the Negroes live, black men of property and university training can be, and usually are, by law denied the ballot, while the most ignorant white man votes. This attempt to put the personal and property rights of the best of the blacks at the absolute political mercy of the worst of the whites is spreading each day.

(6) Oswald Garrison Villard wrote a letter of protest to Booker T. Washington about speeches he had been making in Europe about African American civil rights in the United States (January, 1910)

From my point of view your philosophy is wrong. You are keeping silent about evils in regard to which you should speak out, and you are not helping the race by portraying all the conditions as favorable. If my grandfather had gone to Europe, say in 1850, and dwelt in his speeches on slavery upon certain encouraging features of it, such as the growing anger and unrest of the poor whites, and stated the number of voluntary liberations and number of escapes to Canada, as evidence that the institution was improving, he never would have accomplished what he did, and he would have hurt, not helped, the cause of freedom. It seems to me that the parallel precisely affects your case. It certainly cannot be unknown to you that a greater and greater percentage of the intellectual colored people are turning from you, and becoming your opponents, and with them a number of white people as well.

(7) Booker T. Washington reply to Oswald Garrison Villard about his lecture tour of Europe (January, 1910)

There is little parallel between conditions in your grandfather had to confront and those facing us now. Your grandfather faced a great evil which was to be destroyed. Ours is a work of construction rather than a work of destruction. My effort in Europe was to show to the people that the work of your grandfather was not wasted and that the progress the Negro has made in America justified the words and work of your grandfather. You of course, labour under the disadvantage of not knowing as much about the life of the Negro race as if you were a member of the race yourself.

(8) Ray Stannard Baker, American Magazine (1908)

Nothing has been more remarkable in the recent history of the Negro than Washington's rise to influence as a leader, and the spread of his ideals of education and progress. It is noteworthy that he was born in the South, a slave, that he knew intimately the common struggling life of the people and the attitude of the white race toward them. The central idea of his doctrine is work. He teaches that if the Negro wins by real worth a strong economic position in the country, other rights and privileges will come to him naturally. He should get his rights, not by gift of the white man, but by earning them himself.

Whenever I found a prosperous Negro enterprise, a thriving business place, a good home, there I was almost sure to find Booker T. Washington's picture over the fireplace or a little framed motto expressing his gospel of work and service. Many highly educated Negroes, especially, in the North, dislike him and oppose him, but he has brought new hope and given new courage to the masses of his race. He has given them a working plan of life. And is there a higher test of usefulness? Measured by any standard, white or black, Washington must be regarded today as one of the great men of this country: and in the future he will be so honored.

(9) Ida Wells was one of the first members of the NAACP. In her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928), Wells points out that the NAACP was concerned about the activities of Booker T. Washington in the struggle for racial equality.

There was an uneasy feeling that Mr. Booker T. Washington and his theories, which seemed for the moment to dominate the country, would prevail in the discussion as to what ought to be done. Although the country at large seemed to be accepting and adopting Mr. Washington's theories of industrial education, a large number agreed with Dr. Du Bois that it was impossible to limit the aspirations and endeavors of an entire race within the confines of the industrial education program.

(10) When Booker T. Washington died, William Du Bois wrote an article about him in The Crisis (14th November, 1915)

Booker T. Washington was the greatest Negro leader since Frederick Douglass, and the most distinguished man, white or black who has come out of the South since the Civil War. On the other hand, in stern justice, we must lay on the soul of this man, a heavy responsibility for the consummation of Negro disfranchisement, the decline of the Negro college and the firmer establishment of color caste in this land.