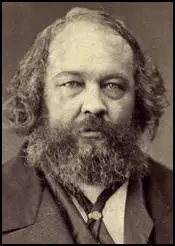

Mikhail Bakunin

Mikhail Bakunin was born in Premukhino, Russia on 30th May, 1814. The eldest son of a landowner he entered the Imperial Russian Artillery School at the age of fourteen.

Bakunin became an army officer in 1833 but after being sent to the Polish frontier he resigned his commission and began studying philosophy. As a young man he met and was deeply influenced by the radical philosopher, Alexander Herzen. He was impressed with Bakunin and later commented: "This man was born not under an ordinary star but under a comet."

Bakunin left Russia in 1842 and lived in Dresden before moving to Paris where he met Karl Marx. He participated in the 1848 French Revolution and then moved to Germany where he called for the overthrow of the Habsburg Empire. The composer, Richard Wagner met him during this period and later pointed out: "Everything about him was colossal and he was full of a primitive exuberance and strength." His biographer, Paul Avrich, added: "His broad magnanimity and childlike enthusiasm, his burning passion for liberty and equality, and his volcanic onslaughts against privilege and injustice all gave him enormous appeal in the libertarian circles of his day."

During the Dresden Insurrection in May, 1849, Bakunin was arrested and sentenced to death. He was reprieved and extradited to Austria where he was wanted for his role in the Czech Republic Revolt. He was once again found guilty and sentenced to death. This was eventually commuted and in 1851 he was passed on to the Russian government and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg. In 1854 he was transferred to to the Shlisselburg Fortress and stayed there until 1857 when he was exiled to Siberia.

In 1861 Bakunin managed to escape from Tomsk and reached Japan on 16th August. Paul Avrich has argued: "Despite his years of confinement, he still possessed much of his old vitality and exuberance. He had aged, to be sure, had lost his teeth from scurvy and grown quite fat. But the grey-blue eyes retained their penetrating brilliance; and his voice, eloquence, and physical bulk combined to make him the center of attention."

In September 1861, Bukunin arrived in San Francisco. Over the next few weeks he visited New York City and Boston, where he met John Andrew, George B. McClellan, Charles Sumner and Henry Wilson. Over the next few weeks he mixed with Radical Republicans. He wrote to his friend, Alexander Herzen, that he was very interested in the American Civil War and that "my sympathies are all with the North".

Bakunin also visited his old friend, Louis Agassiz. He introduced him to Henry Longfellow. That night he recorded in his diary: "George Sumner and Mikhail Bakunin to dinner. Mr. Bakunin is a Russian gentleman of education and ability - a giant of a man, with a most ardent, seething temperament. He was in the Revolution of Forty-eight; has seen the inside of prisons of Olmiitz, even, where he had Lafayette's room. Was afterwards four years in Siberia; whence he escaped in June last, down the Amoor, and then in an American vessel by way of Japan to California, and across the isthmus, hitherward. An interesting man." Annie, Longfellow's daughter added that Bukunin was a "big creature with a big head, wild bushy hair, big eyes, big mouth, a big voice and still bigger laugh."

Bakunin enjoyed his time in America, claiming that "the most imperfect republic is a thousand times better than the most enlightened monarchy". He added that the United States and Britain were the "only two great countries" where the people possessed genuine "liberty and political power" where even "the most disinherited and miserable foreigners".

Bakunin eventually reached London where he joined his old friend, Alexander Herzen. The two men worked together on the journal, The Bell, until 1863 when Bakunin went to join the insurrection in Poland. However, he failed to reach his destination and after a spell in Sweden he moved to Italy before settling in Geneva in 1868.

Bakunin had a great influence on radical young students in Russia. In March 1869 he met Sergi Nechayev Soon afterwards Bakunin wrote to James Guillaume that: "I have here with me one of those young fanatics who know no doubts, who fear nothing, and who realize that many of them will perish at the hands of the government but who nevertheless have decided that they will not relent until the people rise. They are magnificent, these young fanatics, believers without God, heroes without rhetoric."

In 1869 he co-wrote Catechism of a Revolutionist with Sergi Nechayev. It included the famous passage: "The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it."

In August, 1869, Nechayev returned to Russia and settled in Moscow where he set up a secret terrorist organization, People's Retribution. When one of its members, Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov, questioned Nechayev's political ideas, he murdered him. The body was weighted down with stones and dumped through an ice hole in a nearby pond. He told the rest of the group, "the ends justify the means".

Sergi Nechayev escaped from Moscow but after discovering the body, some three hundred revolutionaries were arrested and imprisoned. Nechayev arrived in Locarno, where Mikhail Bakunin was living, in January 1870. At first Bakunin was pleased to see Nechayev but the relationship soon deteriorated. According to Z.K. Ralli, Nechayev no longer showed any deference to his mentor. Nechayev told friends that Bakunin had lost the "level of energy and self-abnegation" required to be a true revolutionary. Bakunin wrote that: "If you introduce him to a friend, he will immediately proceed to sow dissension, scandal, and intrigue between you and your friend and make you quarrel. If your friend has a wife or a daughter, he will try to seduce her and get her with child in order to snatch her from the power of conventional morality and plunge her despite herself into revolutionary protest against society."

German Lopatin arrived from Russia with news that it was Nechayev was responsible for the murder of Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov. Mikhail Bakunin wrote to Sergi Nechayev: "I had complete faith in you, while you duped me. I turned out to be a complete fool. This is painful and shameful for a man of my experience and age. Worse than this, I spoilt my situation with regard to the Russian and International causes."

Bakunin completely disagreed with Nechayev's approach to anarchism which he called his "false Jesuit system". He argued that the popular revolution must be "invisibly led, not by an official dictatorship, but by a nameless and collective one, composed of those in favour of total people's liberation from all oppression, firmly united in a secret society and always and everywhere acting in support of a common aim and in accordance with a common program." He added: "The true revolutionary organization does not foist upon the people any new regulations, orders, styles of life, but merely unleashes their will and gives wide scope to their self-determination and their economic and social organization, which must be created by themselves from below and not from above.... The revolutionary organization must make impossible after the popular victory the establishment of any state power over the people - even the most revolutionary, even your power - because any power, whatever it calls itself, would inevitably subject the people to old slavery in new form."

Mikhail Bakunin told Sergi Nechayev: "You are a passionate and dedicated man. This is your strength, your valor, and your justification. If you alter your methods, I would wish not only to remain allied with you, but to make this union even closer and firmer." He wrote to N. P. Ogarev that: "The main thing for the moment is to save our erring and confused friend. In spite of all, he remains a valuable man, and there are few valuable men in the world.... We love him, we believe in him, we foresee that his future activity will be of immense benefit to the people. That is why we must divert him from his false and disastrous path."

Bakunin joined the International Working Men's Association (the First International), a federation of radical political parties that hoped to overthrow capitalism and create a socialist commonwealth. Bakunin had several disagreements with Karl Marx, the other prominent figure in the organization. Bakunin opposed Marx's ideas on state socialism, claiming that it would replace one oppressive form of government with another. Bakunin argued: "No theory, no ready-made system, no book that has ever been written will save the world. I cleave to no system."

Peter Lavrov was another member who disagreed with Bakunin about the way change will be achieved. In 1873 Lavrov argued: "The reconstruction of Russian society must be achieved not only for the sake of the people, but also through the people. But the masses are not yet ready for such reconstruction. Therefore the triumph of our ideas cannot be achieved at once, but requires preparation and clear understanding of what is possible at the given moment."

Bakunin was accused of anarchism and in 1872 he was expelled from the First International. The following year Bakunin published his major work, Statism and Anarchy. In the book Bakunin advocated the abolition of hereditary property, equality for women and free education for all children. He also argued for the transfer of land to agricultural communities and factories to labour associations.

Over the last few years of life, Bakunin continued to be active in politics, hoping that he would help to create a world revolution that would enable an international federation of autonomous communities to be created.

Mikhail Bakunin died in Berne, Switzerland, on 1st July, 1876.

Primary Sources

(1) Henry Longfellow, diary entry (27th November, 1861)

George Sumner and Mikhail Bakunin to dinner. Mr. Bakunin is a Russian gentleman of education and ability - a giant of a man, with a most ardent, seething temperament. He was in the Revolution of Forty-eight; has seen the inside of prisons of Olmiitz, even, where he had Lafayette's room. Was afterwards four years in Siberia; whence he escaped in June last, down the Amoor, and then in an American vessel by way of Japan to California, and across the isthmus, hitherward. An interesting man.

(2) Mikhail Bakunin and Sergi Nechayev, Catechism of a Revolutionist (1869)

The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it.

He despises public opinion. He hates and despises the social morality of his time, its motives and manifestations. Everything which promotes the success of the revolution is moral, everything which hinders it is immoral. The nature of the true revolutionist excludes all romanticism, all tenderness, all ecstasy, all love.

(3) Mikhail Bakunin, letter to N. P. Ogarev (2nd November, 1872)

I pity him (Sergei Nechayev) deeply. No one ever did me, and intentionally, as much harm as he did, but I pity him all the same. He was a man of rare energy, and when we met there burned in him a very ardent and pure flame for our poor, oppressed people; our historical and current national misery caused him real suffering. At that time his external behavior was unsavory enough, but his inner self had not been soiled. It was his authoritarianism and his unbridled willfulness which, very regrettably and through his ignorance together with his Machiavellianism and Jesuitical methods, finally plunged him irretrievably into the mire... However, an inner voice tells me that Nechayev, who is lost forever and certainly knows that he is lost, will now call forth from the depths of his being, warped and soiled but far from being base or common, all his primitive energy and courage. He will perish like a hero and this time he will betray nothing and no one. Such is my belief. We shall see if I am right.

(4) Mikhail Bakunin, The Paris Commune and the State Idea (1871)

Communism I abhor because it is a negation of liberty, and without liberty I cannot imagine anything truly human. I detest communism because it concentrates the strength of society in the State, and squanders that strength in its service: because it places all property in the hands of the State, whereas my principle is the abolition of the State itself, the radical extirpation of the principle of authority and tutelage which has enslaved, oppressed and exploited and depraved mankind under the pretext of moralising and civilising men. I want the organisation of society and the distribution of property to proceed from below, by the free voice of society itself; not downwards from above, by the dictate of authority. In this sense, I am a collectivist and not a communist.

(5) Mikhail Bakunin, Marxism, Freedom and the State (1871)

I am a passionate seeker after Truth and a not less passionate enemy of the malignant fictions used by the "Party of Order", the official representatives of all turpitudes, religious, metaphysical, political, judicial, economic, and social, present and past, to brutalise and enslave the world; I am a fanatical lover of Liberty; considering it as the only medium in which can develop intelligence, dignity, and the happiness of man; not official "Liberty", licensed, measured and regulated by the State, a falsehood representing the privileges of a few resting on the slavery of everybody else; not the individual liberty, selfish, mean, and fictitious advanced by the school of Rousseau and all other schools of bourgeois Liberalism, which considers the rights of the individual as limited by the rights of the State, and therefore necessarily results in the reduction of the rights of the individual to zero.

No, I mean the only liberty which is truly worthy of the name, the liberty which consists in the full development of all the material, intellectual and moral powers which are to be found as faculties latent in everybody, the liberty which recognises no other restrictions than those which are traced for us by the laws of our own nature; so that properly speaking there are no restrictions, since these laws are not imposed on us by some outside legislator, beside us or above us; they are immanent in us, inherent, constituting the very basis of our being, material as well as intellectual and moral; instead, therefore, of finding them a limit, we must consider them as the real conditions and effective reason for our liberty.

(6) Mikhail Bakunin, Marxism, Freedom and the State (1871)

This principle, which constitutes besides the essential basis of scientific Socialism, was for the first time scientifically formulated and developed by Karl Marx, the principal leader of the German Communist school. It forms the dominating thought of the celebrated "Communist Manifesto" which an international Committee of French, English, Belgian and German Communists assembled in London issued in 1848 under the slogan: "Proletarians of all lands, unite" This manifesto, drafted as everyone knows, by Messrs. Marx and Engels, became the basis of all the further scientific works of the school and of the popular agitation later started by Ferdinand Lassalle in Germany.

This principle is the absolute opposite to that recognised by the Idealists of all schools. Whilst these latter derive all historical facts, including the development of material interests and of the different phases of the economic organisation of society, from the development of Ideas, the German Communists, on the contrary, want to see in all human history, in the most idealistic manifestations of the collective as well as the individual life of humanity, in all the intellectual, moral, religious, metaphysical, scientific, artistic, political, juridical, and social developments which have been produced in the past and continue to be produced in the present, nothing but the reflections or the necessary after-effects of the development of economic facts. Whilst the Idealists maintain that ideas dominate and produce facts, the Communists, in agreement besides with scientific Materialism say, on the contrary, that facts give birth to ideas and that these latter are never anything else but the ideal expression of accomplished facts and that among all the facts, economic and material facts, the pre-eminent facts, constitute the essential basis, the principal foundation of which all the other facts, intellectual and moral, political and social, are nothing more than the inevitable derivatives.

(7) Mikhail Bakunin, Marxism, Freedom and the State (1871)

All work to be performed in the employ and pay of the State - such is the fundamental principle of Authoritarian Communism, of State Socialism. The State having become sole proprietor--at the end of a certain period of transition which will be necessary to let society pass without too great political and economic shocks from the present organisation of bourgeois privilege to the future organisation of the official equality of all--the State will be also the only Capitalist, banker, money-lender, organiser, director of all national labour and distributor of its products. Such is the ideal, the fundamental principle of modern Communism.

The Communist idea later passed into more serious hands. Karl Marx, the undisputed chief of the Socialist Party in Germany - a great intellect armed with a profound knowledge, whose entire life, one can say it without flattering, has been devoted exclusively to the greatest cause which exists to-day, the emancipation of labour and of the toilers - Karl Marx who is indisputably also, if not the only, at least one of the principal founders of the International Workingmen's Association, made the development of the Communist idea the object of a serious work. His great work, Capital, is not in the least a fantasy, an "a priori" conception, hatched out in a single day in the head of a young man more or less ignorant of economic conditions and of the actual system of production. It is founded on a very extensive, very detailed knowledge and a very profound analysis of this system and of its conditions. Karl Marx is a man of immense statistical and economic knowledge. His work on Capital, though unfortunately bristling with formulas and metaphysical subtleties which render it unapproachable for the great mass of readers, is in the highest degree a scientific or realist work: in the sense that it absolutely excludes any other logic than that of the facts.

Living for very nearly thirty years, almost exclusively among German workers, refugees like himself and surrounded by more or less intelligent friends and disciples belonging by birth and relationship to the bourgeois world, Marx naturally has managed to form a Communist school, or a sort of little Communist Church, composed of fervent adepts and spread all over Germany. This Church, restricted though it may be on the score of numbers, is skilfully organised, and thanks to its numerous connections with working-class organisations in all the principal places in Germany, it has already become a power. Karl Marx naturally enjoys an almost supreme authority in this Church, and to do him justice, it must be admitted that he knows how to govern this little army of fanatical adherents in such a way as always to enhance his prestige and power over the imagination of the workers of Germany.

(8) Mikhail Bakunin, Marxism, Freedom and the State (1871)

Any State, under pain of perishing and seeing itself devoured by neighbouring States, must tend towards complete power, and, having become powerful, it must embark on a career of conquest, so that it shall not be itself conquered; for two powers similar and at the same time foreign to each other could not co-exist without trying to destroy each other. Whoever says conquest, says conquered peoples, enslaved and in bondage, under whatever form or name it may be.

It is in the nature of the State to break the solidarity of the human race and, as it were, to deny humanity. The State cannot preserve itself as such in its integrity and in all its strength except it sets itself up as supreme and absolute be-all and end-all, at least for its own citizens, or to speak more frankly, for its own subjects, not being able to impose itself as such on the citizens of other States unconquered by it. From that there inevitably results a break with human, considered as univesrsal, morality and with universal reason, by the birth of State morality and reasons of State. The principle of political or State morality is very simple. The State, being the supreme objective, everything that is favourable to the development of its power is good; all that is contrary to it, even if it were the most humane thing in the world, is bad. This morality is called Patriotism. The International is the negation of patriotism and consequently the negation of the State. If therefore Marx and his friends of the German Socialist Democratic Party should succeed in introducing the State principle into our programme, they would kill the International.

(9) Paul Avrich, Anarchist Portraits (1990)

Bukunin's legacy has been an ambivalent one. This was because Bakunin himself was a man of paradox, possessed of an ambivalent nature. A nobleman who yearned for a peasant revolt, a libertarian with an urge to dominate others, an intellectual with a powerful anti-intellectual streak, he could preach unrestrained liberty while fabricating a network of secret organizations and demanding from his followers unconditional obedience to his will. In his Confession to the tsar, he was capable of appealing to Nicholas l to carry the banner of Slavdom into western Europe and do away with the effete parliamentary system. His pan-Slavism and anti-intellectualism, his hatred of Germans and Jews (Marx, of course, being both), his cult of violence and revolutionary immoralism, his hatred of liberalism and reformism, his faith in the peasantry and Lumpenprolctariat - all this brought him uncomfortably close to later authoritarian movements of both the left and the right, movements from which Bakunin himself ould have recoiled in horror had he lived to see their mercurial rise....

Bakunin foresaw that the great revolutions of our time would emerge from the "lower depths" of comparatively undeveloped countries. He saw decadence in advanced civilization and vitality in backward nations. He insisted that the revolutionary impulse was strongest where men had no property, no regular employment, no stake in things as they were; and this meant that the universal upheaval of his dreams would start in the south and east of Europe rather than in such prosperous and stable countries as England or Germany.

These revolutionary visions were closely related to Bakunin's early pan-Slavism. In 1848 he spoke of the decadence of western Europe and saw hope in the more primitive, less industrialized Slavs for the regeneration of the Continent. Convinced that an essential condition for a European revolution was the breakup of the Austrian Empire, he called for its replacement by independent Slavic republics, a dream realized seventy years later. He correctly anticipated the future importance of Slavic nationalism, and he saw, too, that a revolution of Slavs would precipitate the social transformation of Europe. He prophesied, in particular, a messianic role for his native Russia akin to that of the Third Rome of the past and the Third International of the future. "The star of revolution," he wrote in 1848, "will rise high above Moscow from a sea of blood and fire, and will turn into the lodestar to lead a liberated humanity."

We can see then why Bakunin, rather than Marx, can claim to be the true prophet of modern revolution. The three greatest revolutions of the twentieth century - in Russia, Spain, and China-have all occurred in relatively backward countries and have largely been "peasant wars" linked with outbursts of the urban poor, as Bakunin predicted. The peasantry and the unskilled workers, groups for whom Marx expressed disdain, have become the mass base of twentieth-century social upheavals - upheavals which, though often labeled "Marxist," are more accurately described as "Bakuninist." Bakunin's visions, moreover, have anticipated the social ferment within the Third World, the modern counterpart on a global scale of Bukunin's backward, peripheral Europe.