Lou Rogers

Annie (Lou) Rogers, the daughter of Luther Bailey Rogers and Mary Elizabeth Barker, was born in Patten, Maine in 1879. Her father had been a colonel in the Union Army during the American Civil War. As a child she loved to draw producing sketches and caricatures. (1)

Mary Rogers later recalled: "Annie (Lou) was born with a grievance - namely, being a mere girl when she would so much rather be a boy! She consoled herself with dressing in her brother's clothing and taking a boy's part in all their games." (2)

After studying at Massachusetts Art School and Arts Students League in New York she attempted to become a cartoonist. In 1908 an editor said there were "no women cartoonists... "they said women couldn't even draw jokes. They hadn't any humor". (3)

Rogers refused to be beaten. "I came to New York without a cent and without knowing a soul. I was unskilled. I had not the slightest idea of how to tap the city's resources. I was certain of only one thing: I would be a cartoonist.... I used the name Lou, which turned out to be a tremendous help in the days when editors were so prejudiced they could not see humor in a cartoon if they first saw a feminine name attached." (4)

Some of her first cartoons appeared in New York Call. Established in 1908 it eventually became America's leading socialist newspaper. Charles Edward Russell became associate editor and he recruited radicals such as Agnes Smedley, Margaret Sanger, Kate Richards O'Hare, Eugene Debs and Elizabeth Flynn.to write articles for the newspaper. Lou Rogers and Robert Minor provided the cartoons. (5)

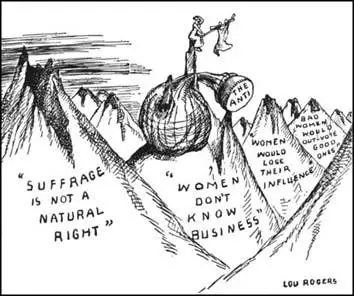

Rogers also had her cartoons published in the Ladies' Home Journal and the New York Tribune. During this period Rogers became one of the first women to develop a career as a cartoonist. (6) Her greatest success came with the popular humor magazine, The Judge where they launched a feature page, "The Modern Woman" on behalf of suffrage. It contained jokes and anecdotes on the campaigns around a central cartoon produced by Rogers. (7)

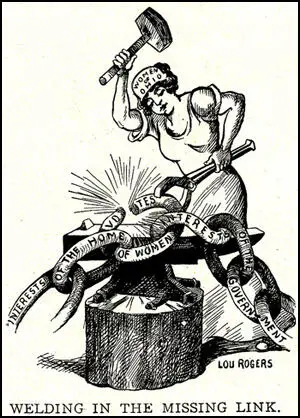

In August 1912, Lou Rogers published Welding in the Missing Link. (8) She explained in a 1913 interview that her cartoons were "a chance to help women see their own problems, help bring out the things that are true in the traditions that have bound them; help show up the things that are false." (9)

Rogers took a keen interest in politics and was a committed supporter of women's suffrage and saw her cartoons as a means of educating the public. As she pointed out in an article A Woman Destined to Do Big Things (1913): "Better than almost any other medium, the picture can make a woman see the truth about the conditions into which her daughter and her neighbor's daughter go, and into which, through changes of circumstances, she herself may be forced to go." (10)

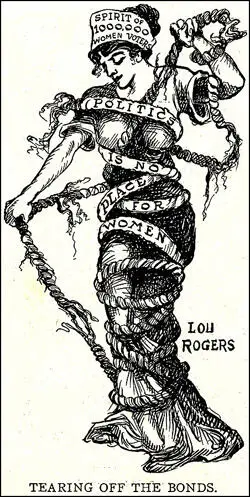

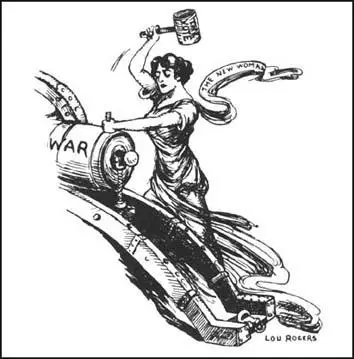

In October, 1912, Lou Rogers published Tearing off the Bonds. (11) Mary Anne Carter argued: "It is easy to see why Rogers enjoyed such a successful career. Her images are not only appealing but they also are suffused with a sense of empowerment. The women in her cartoons in Judge magazine all take decisive action to correct whatever wrong they are being faced with, literally breaking free from shackles, disciplining bad politicians, vacuuming away old-fashioned ideas, and engaging in other empowering activities." (12)

It has been claimed by Jill Lepore in her book The Secret History of Wonder Woman (2015) the Rogers's cartoons influenced the imagery of Wonder Woman. (13) This idea is reinforced by the fact that Harry G. Peter, who produced the first drawings for the Wonder Woman character worked alongside Rogers at The Judge magazine. (14)

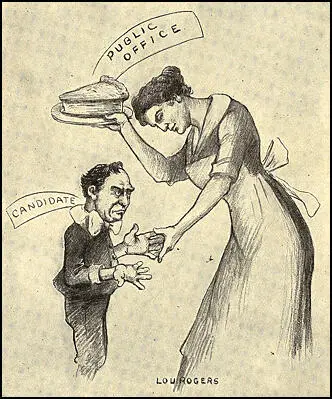

Another important cartoon during this period was Transferring the Mother Habit to Politics. (15) She was skilled in symbolic imagery and adapted nineteenth-century cartooning conventions to convey her message. Transferring the Mother Habit to Politics relies on the traditional woman's role as housekeeper/mother to extract virtue from her reluctant son (the politician). The female figure embodies strength and competence and, appropriate to the parent-child dyad, she is considerably larger than the male. In this cartoon and others Rogers incorporated a housekeeping motif to show how women would end corruption and purify the government." (16)

Rogers contributed cartoons to the Suffragist, Woman Citizen, Women Voter and the Woman's Journal. Rogers also took part in suffrage lecture tours and was a well-known soap-box orator in Times Square. Blanche Ames and Nina Allender were also important cartoonists at the time. "The three of them began to turn things around with their political cartoons that were witty, sharp, and attacking the power that was trying to silence them. This new and modern-day women that was being depicted as the Allender girl, showed a spirit of daring and pride as well as possessing youth." (17)

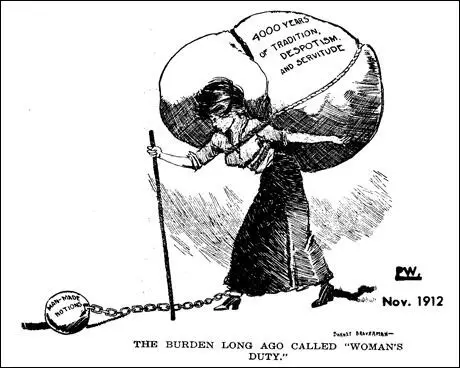

As Holly Bass has pointed out: "The women's suffrage movement had a serious image problem at the turn of the century, when female activists were often portrayed as obsessed feminists out to destroy American society. From 1912-15, three women artists - Annie Lucasta "Lou" Rogers, Nina Allender, and Blanche Ames - helped turn things around with political cartoons that were sharp, witty attacks on the powers that be. These works also stand as some of the first realistic representations of the 'new woman' in the popular media." (18)

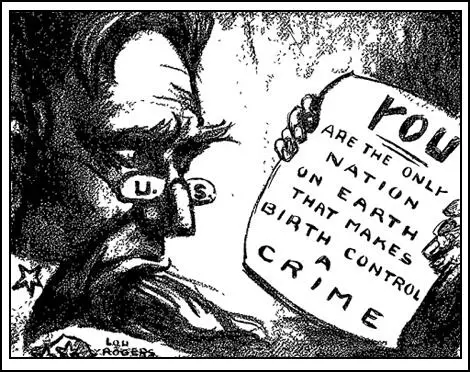

Rogers was a close associate of Margaret Sanger and in 1918 she joined her Birth Control Review as one of three art editors. Birth control was legal in the U.S. for much of the 19th century, but the 1873 Comstock Act had made contraception and the dissemination of information about birth control illegal. Sanger published her journal in violation of the act, and Rogers contributed full-page cartoons in the publication. Alice Sheppard has argued: "To be a woman in turn-of-the-century America was, for Rogers, to be powerless, oppressed, and exploited. She interpreted democracy to imply freedom, justice, and equality - ideals which men had subverted for their use alone." (19)

Rogers created a full-color children's feature called "The Gimmicks" for Ladies' Home Journal. In the 1920s, Rogers married Howard Smith, the colorist for the Gimmicks and some of her later works. For the next several decades, the couple continued to collaborate on illustration projects at their beloved farm near Brookfield, Connecticut. (20)

Lou Rogers died of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis on 11th March 1952.

Primary Sources

(1) Lou Rogers, A Woman Destined to Do Big Things (1913)

Better than almost any other medium, the picture can make a woman see the truth about the conditions into which her daughter and her neighbor's daughter go, and into which, through changes of circumstances, she herself may be forced to go.

(2) Lou Rogers, Lewiston Daily Sun (28th January, 1924)

I decided to be a cartoonist. I came to New York without a cent and without knowing a soul. I was unskilled. I had not the slightest idea of how to tap the city's resources. I was certain of only one thing: I would be a cartoonist.... I used the name Lou, which turned out to be a tremendous help in the days when editors were so prejudiced they could not see humor in a cartoon if they first saw a feminine name attached...

(3) Alice Sheppard, Suffrage Art and Feminism (1990)

Rogers was a largely self-taught artist who contributed work to suffrage and socialist pages, as well as to the popular humor magazine, Judge. She was skilled in symbolic imagery and adapted nineteenth-century cartooning conventions to convey her message. Transferring the Mother Habit to Politics relies on the traditional woman's role as housekeeper/mother to extract virtue from her reluctant son (the politician). The female figure embodies strength and competence and, appropriate to the parent-child dyad, she is considerably larger than the male. In this cartoon and others Rogers incorporated a housekeeping motif to show how women would end corruption and purify the government… Lou Rogers traced the position of women through various concrete issues – labor, government, economy, taxation, peace. She appealed to universal principles of humanity and foresaw a new social era accompanying women's participation in politics.

(4) Mary Anne Carter, Creativity and Persistence: Art that Fuelled the Fight for Women's Suffrage (August 2020)

The first decades of the 20th century were also notable for the rise of the woman cartoonist. A number of trained women artists - who were also suffragist - were recognized for their talents and published in newspapers and magazines around the country. Most importantly, these cartoons were not one-offs; many artists were valued enough that they were retained as regular contributors, enabling them the latitude to develop a distinct creative style and messaging aesthetic. Lou Rogers was one of the most notable of these early woman cartoonists, and one of the very first American women to make a career as a cartoonist. She was also a suffragist who was actively involved in the National Woman Suffrage Association. She regularly contributed to the Woman's Journal among other publications and was eventually hired as the main cartoonist for Judge magazine's "Modern Woman" section. It is easy to see why Rogers enjoyed such a successful career. Her images are not only appealing but they also are suffused with a sense of empowerment. The women in her cartoons in Judge magazine all take decisive action to correct whatever wrong they are being faced with, literally breaking free from shackles, disciplining bad politicians, vacuuming away old-fashioned ideas, and engaging in other empowering activities. Rogers also created satirical images, like her Dispossessed (fig. 58) in which a hen appears at a "government demonstration" on "how to run a nest without waste" and finds a rooster there.

(5) Holly Bass, Artful Advocacy: Cartoons from the Woman Suffrage Movement (1st September, 1995)

The women's suffrage movement had a serious image problem at the turn of the century, when female activists were often portrayed as obsessed feminists out to destroy American society. From 1912-15, three women artists - Annie Lucasta "Lou" Rogers, Nina Allender, and Blanche Ames - helped turn things around with political cartoons that were sharp, witty attacks on the powers that be. These works also stand as some of the first realistic representations of the "new woman" in the popular media. The majority of the 21 works in "Artful Advocacy: Cartoons From the Woman Suffrage Movement" are by Rogers, whose smart, irreverent humor has an edge even by today's standards. "Fitting a Square Peg Into a Round Hole," for instance, depicts a group of men unsuccessfully pulling a cubical woman into a circle representing the "woman's sphere" - an act of suppression that is still all too common. At the National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1250 New York Ave. NW.

(6) Anna Diamond, New York Times (14 August 2020)

When Alice Paul recruited a cartoonist for her newspaper The Suffragist in 1914, the idea of that activist was already sketched in the public mind and it was not pretty. Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, Americans had encountered countless images showing women suffragists as old, mannish and unattractive. In pursuing the vote, women were portrayed as threatening national values, the sanctity of the home and their husbands' masculinity.

It was impossible to miss such representations. Whether in newspapers, on posters or on buildings around town, "all Americans encountered cartoons," according to Allison K. Lange, author of Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women's Suffrage Movement.

Suffragist artists fought back on a black-and-white battlefield, developing imagery to subvert negative portrayals. In the 1910s, these cartoons were key to America's reimagining who a suffragist was and to winning sympathy for the cause.

Paul enlisted Nina Allender, an artist and women's rights activist, to shape the image of a charming and energetic suffragist for the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (a precursor to the National Woman's Party, or N.W.P.). It was important that the Allender Girl be created in a style that was widely recognizable, according to the historian Rebecca McCarron.

Following in the illustrated tradition of the independent "New Woman" and the era's iconic Gibson and Brinkley Girls, she was a stylish ideal of educated, youthful femininity and middle-class respectability. That was essential to offsetting the N.W.P.'s more militant strategies, like picketing the White House and holding hunger strikes in jail.

Other images, like those distributed by the National American Woman Suffrage Association, rebutted claims that women's voting rights endangered the home. Rose O'Neill, creator of the popular cherubic Kewpie babies, sent her characters marching under banners demanding "Votes for Our Mothers." Cartoons by artists like O'Neill, Blanche Ames Ames and Mary Ellen Sigsbee argued that women needed the vote precisely because they were caring and virtuous mothers, Lange said.

Annie Lucasta Rogers, who adopted the androgynous name Lou Rogers to advance her career, was a member of the radical feminist club Heterodoxy. (Her depiction of a woman tearing off the bonds of disenfranchisement strongly influenced the imagery of Wonder Woman, according to Jill Lepore's book "The Secret History of Wonder Woman.") She explained in a 1913 interview that her cartoons were "a chance to help women see their own problems, help bring out the things that are true in the traditions that have bound them; help show up the things that are false."

Whether the images featured girlish, maternal or symbolic figures, the protagonists, and the artists who drew them, were white. Though there were many women of color who were passionate suffragists, their absence in the cartoons spoke to a larger strategy adopted by many reformers to appease white supremacist politicians and suffragists and obscure the contributions of women who were not white.

The National Association of Colored Women produced portraits of leaders like Mary Church Terrell, but, Lange said, they lacked the same resources and infrastructure to widely shape their public image. One rare example - perhaps the only one - of a cartoon in support of Black women's suffrage was printed in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People's publication The Crisis with the title "Woman to the Rescue!" It shows a Black mother protecting her children against birds of prey representing Jim Crow and segregation.

Soon after the Allender Girl celebrated her hard-won victory in The Suffragist, her creator moved on to Paul's next pursuit - the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, in the pages of the N.W.P.'s new magazine, Equal Rights. But 100 years later, American women are still at that drawing board.

(7) Maren Williams, She Changed Comics: Lou Rogers, Advocate for Women's Rights (17th March, 2017)

Annie Lucasta Rogers was one of seven siblings raised on a farm in northern Maine, where their father owned several logging camps. Their mother, observed Rogers' reporter friend in the Lewiston Daily Sun in 1924, was "the sort of woman who would have made a remarkable journalist had that opportunity been open to her." Rogers herself showed an early talent for caricature, becoming "the bane of teachers and the delight of her classmates," she recalled later in an autobiographical essay for The Nation. She taught school in rural Maine just long enough to save up money to enroll at the Massachusetts Normal Art School (now the Massachusetts College of Art and Design) in Boston.

Rogers' college fund lasted for a year and a half, but she admitted to the Daily Sun reporter that she was not a very disciplined student: "I don't remember that I learned much about drawing. The life of the city was far too enthralling to my backwood eyes, people, street happenings, circus parades, were a heap sight more fascinating than trying to draw pots and pans with charcoal."

In Boston Rogers also developed a keen interest in physical culture, an early fitness movement that promoted exercise among the masses. Along with a classmate, she left art school and embarked on what she later called a "tramp adventure," teaching fitness classes in Chicago and points west...

Rogers' pet issue, unsurprisingly for an independent woman in the 1910s, was women's suffrage. Around this time she undertook another extraordinary journey, traveling around New York and New Jersey for several months, giving what she called "cartoon speeches" for the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA).

Armed with a folding platform-and-easel contraption built by her brother, she expounded on votes for women while also drawing cartoons "in simple Sunday comic style with a wide, flat grease crayon line, black enough to carry two blocks." This was "a most thrilling exhausting job," she told the Sun: "Every ounce of strength one had seemed to be required to hurl the voice into the outskirts of the great crowds that naturally gathered when a woman in an orange smock and cap set up this amazing apparatus….On top of this nervous expenditure the drawing had to be swift and telling and the talk as straight cut as the picture."

Rogers was accustomed to being heckled or even pelted with eggs during her cartoon speeches, but even her detractors were soon captivated by the show since "all people are like little children when it comes to watching a picture grow on a piece of white paper," she observed (Sheppard 1985).

Back in New York City, Rogers landed regular gigs in NWSA's Woman's Journal and the New York Call. In 1912, when Judge started a "Modern Woman" page about suffrage issues, Rogers was the main cartoonist. The publication's art editor Grant Hamilton enthused that "she has what ninety-nine out of a hundred lack, the ability to see the way to get the idea into the picture" (Sheppard 1985).

Rogers' work at Judge may have helped shape one of today's most popular superheroes (Lepore 2014). While at Judge, Rogers worked alongside Harry George Peter, who would occasionally create pieces for "Modern Woman" when Rogers was overbooked. Peter was the original artist behind William Moulton Marston's Wonder Woman. Both Marston and Peter were inspired by the suffrage movement in the creation of the character, and while it cannot be determined whether Peter was influenced directly by Rogers work, it still showed the hallmarks of suffrage artwork.

Rogers' devotion to feminist causes wasn't limited to the 19th Amendment. In 1918 she joined Margaret Sanger's Birth Control Review as one of three art editors. Birth control was legal in the U.S. for much of the 19th century, but the 1873 Comstock Act had made contraception and the dissemination of information about birth control illegal. Sanger published Birth Control Review in violation of the act, and Rogers contributed spot art, full-page cartoons, and spreads to the publication.

After leaving Birth Control Review in 1922, Rogers created a full-color children's feature called "The Gimmicks" for Ladies' Home Journal. Inspired by her fascination with cityscapes that began back in Boston, the Gimmicks were Rogers' idea of uniquely American elves "with the character that would develop from living up high and around queer roof things" such as drainspouts and fire escapes.

In the 1920s, Rogers married Howard Smith, the colorist for the Gimmicks and some of her later works. For the next several decades, the couple continued to collaborate on illustration projects at their beloved farm near Brookfield, Connecticut. Rogers died of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in 1952 at age 72.