Nina Allender

Nina Evans, the daughter of David Evans, a superintendent of schools, was born in Auburn, Kansas, on 25th December, 1872. Her mother, Eva Evans, worked as a prairie school teacher. (1) In 1881 Eva divorced her husband and became a government worker for the Department of the Interior. (2)

Nina wanted to become an art teacher but abandoned this idea after meeting an Englishman by the name of Charles Allender. They married in 1893 but soon afterwards Charles fled for England with another woman and a large sum of money to avoid a prison sentence for embezzlement and forgery. Nina kept the Allender name and took a job with the U.S Treasury Department. (3)

At the age of 38, Nina Allender became actively involved in the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). The leaders of this organisation include Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Chapman Catt, Frances Willard, Matilda Joslyn Gage and Anna Howard Shaw. Over the next few years she became a leading activist in the movement. (4)

In 1912, Allender had volunteered to assist NAWSA's Congressional Committee in planning their March 3, 1912 suffrage pageant in Washington. Allender was appointed chair of the committee on "outdoor meetings" as well as on "posters, post cards and colors." Soon afterwards she became president of the District of Columbia Woman Suffrage Association and was a featured speaker at numerous local gatherings. At this time she was considered to be one of the movement's finest orators. In 1913, Allender joined with Jeannette Rankin and thirteen other women representing different states to meet with President Woodrow Wilson in a suffrage deputation. (5)

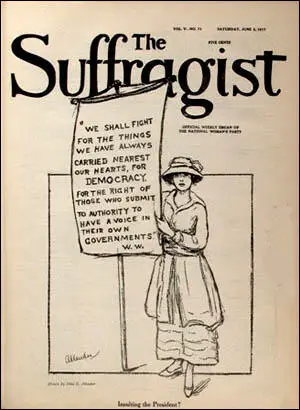

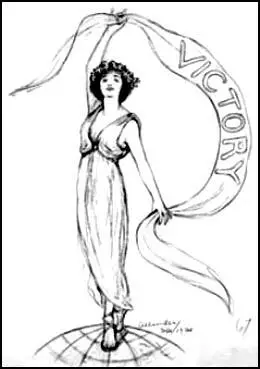

The Suffragist (18th December, 1915)

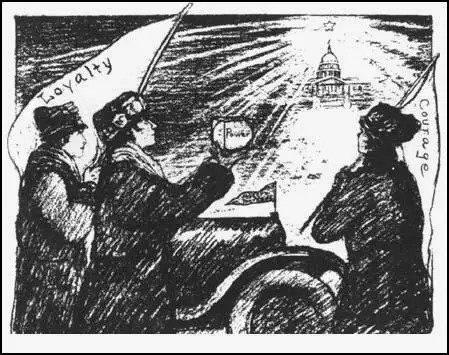

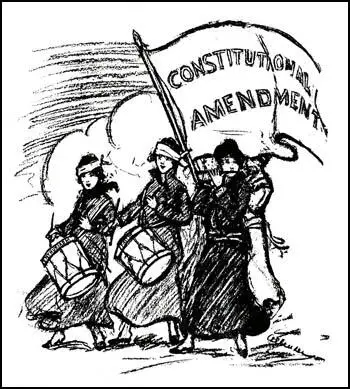

In 1913 Allender joined the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS). Later that year the CUWS started its own magazine, The Suffragist. Its first editor was the veteran muckraking journalist, Rheta Childe Dorr. The magazine published articles by leading members such as Alice Paul, Lucy Burns and Inez Milholland. Allender became Its main cartoonist. The journal also published cartoons by Cornelia Barns, Rollin Kirby and Boardman Robinson. (6)

Yolanda Reynoso Aguilar has argued: "Nina Allender viewed herself as more of a painter, there was hesitation towards the beginning of her endeavors of being a cartoonist. Though that uncertainty became quickly forgotten as her cartoons were showcased weekly on the cover of the Suffragist newspaper. Her cartoons became a trademark... Her earlier works played off traditional gender roles and she soon began to create works that featured that were then labeled as the Allender girl." (7)

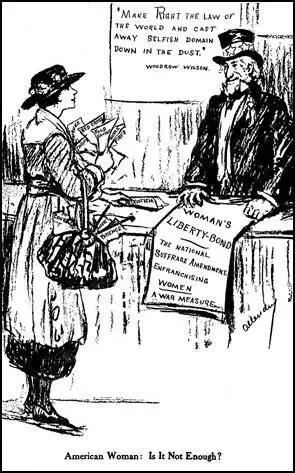

It was said: "She (Nina Allender) gave to the American public in cartoons that have been widely copied and commented on, a new type of suffragist - the young and zealous women of a new generation determined to wait no longer for a just right. It was Mrs. Allender's cartoons more than any other one thing that in the newspapers of this country began to change the cartoonist's idea of the suffragist." (8)

Laura Myers has pointed out: "Male cartoonists often drew suffragists as unattractive old maids with thick spectacles and wielding battle axes, or portrayed them as too hysterical to vote." Allender answered this with portraits of "smart modern women" seeking the vote to gain an equal voice in a male-run government. She quotes Alice Sheppard as saying "you cannot argue against a picture." (9)

It has been claimed that this was a strategy developed by Alice Paul: "When Alice Paul recruited a cartoonist for her newspaper The Suffragist in 1914, the idea of that activist was already sketched in the public mind and it was not pretty. Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, Americans had encountered countless images showing women suffragists as old, mannish and unattractive. In pursuing the vote, women were portrayed as threatening national values, the sanctity of the home and their husbands' masculinity.... Suffragist artists fought back on a black-and-white battlefield, developing imagery to subvert negative portrayals. In the 1910s, these cartoons were key to America's reimagining who a suffragist was and to winning sympathy for the cause." (10)

Allender was not the only cartoonist creating a new image of women fighting for the vote: Lou Rogers and Blanche Ames were also involved in this campaign "The three of them began to turn things around with their political cartoons that were witty, sharp, and attacking the power that was trying to silence them. This new and modern-day women that was being depicted as the Allender girl, showed a spirit of daring and pride as well as possessing youth. " (11)

Allender continued to work for women's rights after the 19th Amendment was passed. She was involved in the campaign for the Equal Rights Amendment and served on its National Council until 1946, when she resigned for health reasons. Her colleague Inez Haynes Irwin wrote: "Her (Nina Allender) work is full of the intimate everyday details of the woman's life from her little girlhood to her old age. And she translates that existence with a woman's vivacity and a woman's sense of humor.... It would be impossible for any man to have done Mrs. Allender's work. A woman speaking to women, about women, in the language of women." (12)

Nina Evans Allender died on 2nd April 1957. (13)

Primary Sources

(1) The Suffragist (23rd February, 1918)

She (Nina Allender) gave to the American public in cartoons that have been widely copied and commented on, a new type of suffragist - the young and zealous women of a new generation determined to wait no longer for a just right. It was Mrs. Allender's cartoons more than any other one thing that in the newspapers of this country began to change the cartoonist's idea of the suffragist.

(2) Yolanda Reynoso Aguilar, Nina Evans Allender (28th May, 2019)

Nina Allender was a woman inspired by her mother to become active during the first wave of feminism. Her greatest contribution was being a cartoonist and reforming how women were being viewed by the public. Allender was a woman that was a driving force in re-defining how women activists were being portrayed.

Charlie Allender is mentioned to be another reason as to why she became interested in women's suffrage. The two of them were not married very long, in fact he did not even divorce her formally. It was just another normal day in Allender's life when Charlie vanished from the bank where he was working at, along with a certain amount of money and an unnamed female coworker. There is no certainty in knowing if that was another event that was significant in her becoming active in the movement. Though according to her relatives Allender was unhappy and a depressed woman afterwards. After some time, she took comfort and followed her mother's example of being independent and strong-willed. Taking control of the life she had and getting a government job for the Treasury Department while also being active in the Arts Club of Washington.

Nina Allender viewed herself as more of a painter, there was hesitation towards the beginning of her endeavors of being a cartoonist. Though that uncertainty became quickly forgotten as her cartoons were showcased weekly on the cover of the Suffragist newspaper. Her cartoons became a trademark... Her earlier works played off traditional gender roles and she soon began to create works that featured that were then labeled as the "Allender girl."

(3) Ashley Nicole Owens and Miranda Pikaart, Nina Allender (2017)

Nina Allender was born in Auburn, Kansas in 1872 to David Evans, who moved to Kansas to be the Superintendent of Schools, and Eva Evans, who worked as a prairie school teacher. In 1881, Nina's mother divorced her father and became a government worker for the Department of the Interior. Young Nina and her mother moved in with her aunt Kate. Nina studied painting as a girl and went on to attend the Corcoran School of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. She married Charles Allender in 1893. Charles Allender accepted a banking position arranged by Nina's family, but early in their marriage Charles fled for England with a large sum of money to avoid a prison sentence for embezzlement and forgery. Nina kept the Allender name and took a job with the U.S Treasury Department.

Even though she worked full time Allender became actively involved in the suffrage movement in 1912. She was the president of the Stanton Suffrage Club in D.C. and served in the National Woman's Party by traveling to Wyoming to help with the campaign there. She also assisted in creating advertisements for parades and lectures.

Allender's primary contribution to the suffrage campaign was as the main cartoonist for The Suffragist. With this work, she helped reshape the topics that women cartoonists could take on. The majority of women cartoonists had been limited to "womanly subjects" of children and family life rather than political commentary. Many women in the field were also limited to coloring in designs created by men.

Suffragists drawn by male cartoonists for newspapers and magazines were depicted as austere, manly, or haggard troublemakers. Allender transformed the negative image of suffragists into attractive yet serious and determined young women dedicated to winning the vote. This new image was often called the "Allender girl." Nina did not shy away from political subjects at all; her main characters were the Democratic Donkey, Congress, Woodrow Wilson and Uncle Sam. She often used the president's own words in her messages for woman's suffrage, a strategy used by the National Woman's Party. Nina Allender's cartoons represented women in a positive manner, as capable of rational political thought. Members of the NWP were convinced that the cartoons were influential and persuasive in ways words and arguments were not, and they often featured her work on the cover of The Suffragist.

(4) Holly Bass, Artful Advocacy: Cartoons from the Woman Suffrage Movement (1st September, 1995)

The women's suffrage movement had a serious image problem at the turn of the century, when female activists were often portrayed as obsessed feminists out to destroy American society. From 1912-15, three women artists - Annie Lucasta "Lou" Rogers, Nina Allender, and Blanche Ames - helped turn things around with political cartoons that were sharp, witty attacks on the powers that be. These works also stand as some of the first realistic representations of the "new woman" in the popular media. The majority of the 21 works in "Artful Advocacy: Cartoons From the Woman Suffrage Movement" are by Rogers, whose smart, irreverent humor has an edge even by today's standards. "Fitting a Square Peg Into a Round Hole," for instance, depicts a group of men unsuccessfully pulling a cubical woman into a circle representing the "woman's sphere" - an act of suppression that is still all too common. At the National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1250 New York Ave. NW.

(5) Anna Diamond, New York Times (14 August 2020)

When Alice Paul recruited a cartoonist for her newspaper The Suffragist in 1914, the idea of that activist was already sketched in the public mind and it was not pretty. Throughout the 19th century and into the 20th, Americans had encountered countless images showing women suffragists as old, mannish and unattractive. In pursuing the vote, women were portrayed as threatening national values, the sanctity of the home and their husbands' masculinity.

It was impossible to miss such representations. Whether in newspapers, on posters or on buildings around town, "all Americans encountered cartoons," according to Allison K. Lange, author of Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women's Suffrage Movement.

Suffragist artists fought back on a black-and-white battlefield, developing imagery to subvert negative portrayals. In the 1910s, these cartoons were key to America's reimagining who a suffragist was and to winning sympathy for the cause.

Paul enlisted Nina Allender, an artist and women's rights activist, to shape the image of a charming and energetic suffragist for the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (a precursor to the National Woman's Party, or N.W.P.). It was important that the Allender Girl be created in a style that was widely recognizable, according to the historian Rebecca McCarron.

Following in the illustrated tradition of the independent "New Woman" and the era's iconic Gibson and Brinkley Girls, she was a stylish ideal of educated, youthful femininity and middle-class respectability. That was essential to offsetting the N.W.P.'s more militant strategies, like picketing the White House and holding hunger strikes in jail.

Other images, like those distributed by the National American Woman Suffrage Association, rebutted claims that women's voting rights endangered the home. Rose O'Neill, creator of the popular cherubic Kewpie babies, sent her characters marching under banners demanding "Votes for Our Mothers." Cartoons by artists like O'Neill, Blanche Ames Ames and Mary Ellen Sigsbee argued that women needed the vote precisely because they were caring and virtuous mothers, Lange said.

Annie Lucasta Rogers, who adopted the androgynous name Lou Rogers to advance her career, was a member of the radical feminist club Heterodoxy. (Her depiction of a woman tearing off the bonds of disenfranchisement strongly influenced the imagery of Wonder Woman, according to Jill Lepore's book "The Secret History of Wonder Woman.") She explained in a 1913 interview that her cartoons were "a chance to help women see their own problems, help bring out the things that are true in the traditions that have bound them; help show up the things that are false."

Whether the images featured girlish, maternal or symbolic figures, the protagonists, and the artists who drew them, were white. Though there were many women of color who were passionate suffragists, their absence in the cartoons spoke to a larger strategy adopted by many reformers to appease white supremacist politicians and suffragists and obscure the contributions of women who were not white.

The National Association of Colored Women produced portraits of leaders like Mary Church Terrell, but, Lange said, they lacked the same resources and infrastructure to widely shape their public image. One rare example - perhaps the only one - of a cartoon in support of Black women's suffrage was printed in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People's publication The Crisis with the title "Woman to the Rescue!" It shows a Black mother protecting her children against birds of prey representing Jim Crow and segregation.

Soon after the Allender Girl celebrated her hard-won victory in The Suffragist, her creator moved on to Paul's next pursuit - the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, in the pages of the N.W.P.'s new magazine, Equal Rights. But 100 years later, American women are still at that drawing board.