The 1864 Andersonville Prison Camp Atrocity

During the early stages of the American Civil War the federal government refused to negotiate the exchange of prisoners as it did not recognize the Confederacy as a nation. In July, 1862, General John Dix of the Union Army and General D. H. Hill met and agreed an exchange. They decided that the rate of exchange was one general for every 60 enlisted men, a colonel for 15, a lieutenant for 4 and a sergeant for 2.

In 1863 General Henry Halleck became the Union representative involved in the exchange of prisoners. Under pressure from Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War, these exchanges became less frequent. When Ulysses S. Grant became overall commander of the Union Army he brought an end to exchanges. General Benjamin F. Butler later said what Grant had told him: "He (Grant) said that I would agree with him that by the exchange of prisoners we get no men fit to go into our army, and every soldier we gave the Confederates went immediately into theirs, so that the exchange was virtually so much aid to them and none to us."

The decision of Ulysses S. Grant resulted in a rapid increase in the number of prisoners and so it was decided to build Andersonville Prison in Georgia. It was to be the Confederate's largest prison for captured soldiers. In April, 1864, General John Henry Winder, who was now in charge of all Union Army prisoners east of the Mississippi, appointed Henry Wirz as commandant of this new prison camp.

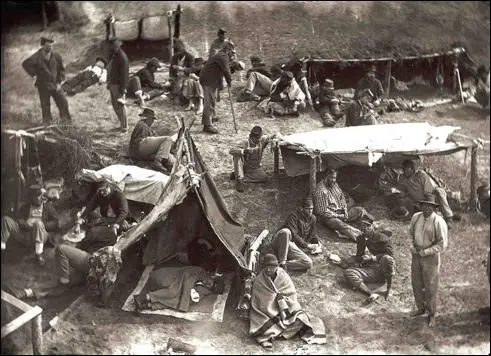

By August, 1864, there were 32,000 Union Army prisoners in Andersonville. The Confederate authorities did not provide enough food for the prison and men began to die of starvation. The water became polluted and disease was a constant problem. Of the 49,485 prisoners who entered the camp, nearly 13,000 died from disease and malnutrition.

When the Union Army arrived in Andersonville in May, 1865, photographs of the prisoners were taken and the following month they appeared in Harper's Weekly. The photographs caused considerable anger and calls were made for the people responsible to be punished for these crimes. It was eventually decided to charge General Robert Lee, James Seddon, the Secretary of War, and several other Confederate generals and politicians with "conspiring to injure the health and destroy the lives of United States soldiers held as prisoners by the Confederate States".

In August, 1865 President Andrew Johnson ordered that the charges against the Confederate generals and politicians should be dropped. However, he did give his approval for Henry Wirz to be charged with "wanton cruelty". Wirz appeared before a military commission headed by Major General Lew Wallace on 21st August, 1865. During the trial a letter from Wirz was presented that showed that he had complained to his superiors about the shortage of food being provided for the prisoners. However, former inmates at Andersonville testified that Wirz inspected the prison every day and often warned that if any man escaped he would "starve every damn Yankee for it." When Wirz fell ill during the trial Wallace forced to attend and was brought into court on a stretcher.

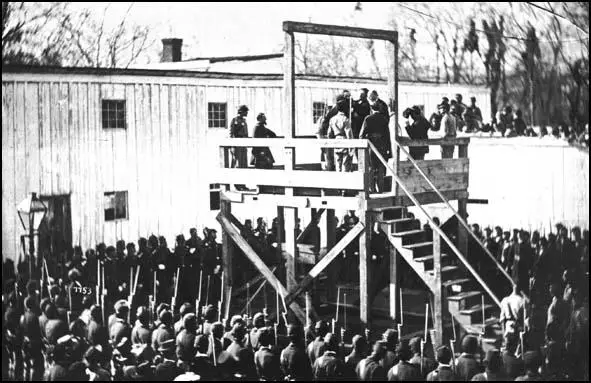

Henry Wirz was found guilty on 6th November and sentenced to death. He was taken to Washington to be executed in the same yard where those involved in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln had died. Alexander Gardner, the famous photographer, was invited to record the event.

The execution took place on the 10th November. The gallows were surrounded by Union Army soldiers who throughout the procedure chanted "Wirz, remember, Andersonville." Accompanied by a Catholic priest, Wirz refused to make a last minute confession, claiming he was not guilty of committing any crime.

the death warrant to Henry Wirz on the gallows at Washington Penitentiary.

Major Russell read the death warrant and then told Henry Wirz he "deplored this duty."Wirz replied that: "I know what orders are, Major. And I am being hanged for obeying them."

After a black hood was placed over his head, and the noose adjusted, a spring was touched and the trap door opened. However, the drop failed to break his neck and it took him two minutes to die. During this time the soldiers continued to chant: "Wirz, remember, Andersonville."

Primary Sources

(1) H. J. Winser, New York Times (26th November, 1864)

The past few days have been fraught with a very painful interest to everybody who has been connected in any way whatever with the exchange of our sick and wounded prisoners now in progress on the Savannah River. Colonel Mulford began to receive our poor fellows last Friday, and the delivery is to continue at the rate of from eight hundred to twelve hundred per day, until the aggregate number of the wretched suffering creatures, estimated at ten thousand, return to our welcome keeping. I shall attempt in this letter to give some idea of the outward appearance, physical condition, animating spirit and expression of opinion of these soldiers of the Republic who have escaped from unutterable misery, with the sole object of presenting facts to the county which must result in the release of their fifty thousand comrades who cannot survive the coming Winter, under the conditions in which they are kept through the unparalleled vindictiveness of the Southern authorities. This is a hard charge, but I make it deliberately. The irrefragable proof is lying before me not alone in the ex parte testimony and wasted hungry aspect of the sufferers, whose filth and squalor and skeleton frames appeal for justice to the God of justice, but in the official papers of the rebel surgeons at Andersonville and the records of the charnel-houses, miscalled hospitals, at that terrestrial hell - records never meant to pass the limits of the Confederacy, but which a merciful Providence has brought to light, that out of their own mouths these barbarians, with whom we are at war, should be convicted.

When the rebel boat moves off and the men are huddled together on the decks of our own vessels, all fully understand that the last link which bound them to rebeldom has been severed, then rises hearty shouting and cheering, which only can be given under these circumstances. There is the music of intense gratefulness in it. Three cheers and a tiger for the old flag; there more and a tiger for Colonel Mulford; then comes a burst of song, most often the words being "Rally round the flag, boys, from near and from far, down with the traitor and up with the star," the rebels still within hearing, probably gnashing their teeth at the pointed personal allusion, but everybody else feeling that the bad taste of the happy fellow is excusable, even though exhibited under the sacred folds of a flag of truce. Then vermin infested rags, till now highly prized as the only cover for nakedness, are rudely torn off and flung into the water or cast with glee into the flaming furnaces of the steamers, and new clothes are issued, and a general cleaning-time inaugurated. But the bathing has long been needed and scarcely comes soon enough. Many of the men, through illness or carelessness, are so begrimed with filth, that, were it not for the dead color of the blackened epidermis, they might be taken for the sons of Ham.

It is a touching sight to see them, each with his quart can, file by the steaming coffee barrels, and receive the refreshing draught whose taste has long been unfamiliar. It seems scarcely possible that men should feel such childish joy as they express in once more receiving this common stimulant. And then, the eager, hungry glare which their glassy eyes cast upon the chunks of ham as they clutch and devour their allowance with a wolf-like avidity.

Such is the condition of the men whom we are now receiving out of chivalrous Dixie. These the sons, brothers, husbands and fathers of the North. Men reduced to living skeletons; men almost naked; shoeless men, shirtless men, hatless men; men with no other garment than an overcoat; men whose skins are blackened by dirt and hang on their protruding bones loosely as bark on a tree; men whose very presence is simply disgusting, exhaling an odor so fetid that it almost stops the breath of those unaccustomed to it, and causes an involuntary brushing of the garments if with them there is accidental contact.

(2) Dr. John Bates was assistant surgeon at Andersonville and gave evidence for Henry Wirz at his trial.

Upon going to the hospital I went immediately to the ward to which I was assigned, and, although I am not an over-sensitive man, I must confess I was rather shocked at the appearance of things. The men were lying partially nude and dying, and lousy, a portion of them in the sand and others upon boards which had been stuck up on little props, pretty well crowded together, a majority of them in small tents that were not very serviceable at best. I went around and examined all that were placed in my charge. That was the condition of the men. By and by, as I became familiarized with the condition of affairs, the impressions which were at first produced upon me wore off, more or less. I became familiar with scenes of misery and they did not affect me so much. I inquired into the rations of the men; I felt disposed to do my duty; and after the men found out that I was inclined to aid them so far as I could in my sphere of action, the frequently asked me for a teaspoonful of salt, or an order for a little siftings that came out of the meal, I would ask them what they wanted the siftings for; some of them wished them to make some bread. I would inquire into the state of their disease, and if what they asked for would injure them, I would not allow them to have it. I would give them an order for sifted meal where I found that the condition of the patient required something better than siftings. They would come at times in considerable numbers to get these little orders for an extra ration, or if not a ration, whatever portion they could get.

The meat ration was cooked at a different part of the hospital; and when I would go up there, especially when I was a medical officer of the day, the men would gather around me and ask me for a bone. I would grant their requests so far as I saw bones. I would give them whatever I could find at my disposition without robbing others. I well knew that an appropriation of one ration took it from the general issue; that when I appropriated an extra ration to one man, some one else would fall minus upon that ration. I then fell back upon the distribution of bones. They did not presume to ask me for meat at all. So far as rations are concerned, that is about the way matters went along for some time after I went there.

Clothing we had none; they could not be furnished with any clothing, except that the clothing of the dead was generally appropriated to the living. We thus helped the living as well as we could. Of vermin or lice there was a very prolific crop there. I got to understand practically the meaning of the term "lousy"; I would generally find some upon myself upon returning to my quarters; they were so that it was impossible for a surgeon to enter the hospital without having some upon him when he came out, if he touched anybody or anything save the ground, and very often if he merely stood still any considerable length of time he would get them upon him.

When I went to the hospital I found the men destitute of clothing and bedding; there was a partial supply of fuel, but not sufficient to keep the men warm and prolong their existence. Shortly after I arrived there I was appointed office of the day. I learned that the officer of the day was in supreme command of all pertaining to the hospital, and that it was my duty as such to go into the various wards and divisions of the hospital and rectify anything that needed to be cared for. In visiting the hospital I made a pretty thorough examination. As a general thing, the patients were destitute; they were filthy and partly naked. There seemed to be a disposition only to get something to eat. The clamor all the while was for something to eat. They asked me for orders for this that and the other - peas or rice, or salt, or beef tea, or a potato, or a biscuit, or a piece of corn bread, or siftings, or meal.

Medicines were scarce ; we could not get what we wished. We drew upon the indigenous remedies; they did not seem to answer. We gathered up large quantities of them, but very few served for medicines as we wished. We wanted the best powerful anti-scorbutics, as well as something that was soothing and healing, especially to the lining membrane of the alimentary canal, and such things as were calculated to counteract a dropsical disposition and a gangrenous infection. Those were prominent things in the hospital. We had not at all times the proper remedies to administer, and the indigenous remedies did not serve us, and could not serve us in those complaints. We were obliged to do the best we could.

There was in my ward a boy of fifteen or sixteen years, in whom I felt a particular interest. My attention was more immediately called to him from his youth, and he appealed to me in such a way that I could not well avoid heeding him. He would often ask me to bring him a potato, a piece of bread, a biscuit, or something of that kind, which I did; I would put them in my pocket and give them to him. I would sometimes give him a raw potato, and as he had the scurvy, and also gangrene, I would advise him not to cook the potato at all, but to eat it raw, as an anti-scorbutic. I supplied him in that way for some time, but I could not give him a sufficiency. He became bed-ridden upon the hips and back, lying upon the ground; we afterwards got him some straw. Those bed-ridden sores had become gangrenous. He became more and more emaciated, until he died. The lice, the want of bed and bedding, of fuel and food, were the cause of his death.

We had cases of chilblains or frost-bitten feet. Most generally, in addition to what was said to be frost-bite, there was gangrene. I did not see the sores I the original chilblains. I do not think I can say if there were any amputations or any deaths resulting from suffering of that character, not having charged my mind as to whether the amputations were in consequence of chilblains, or because, from accidental abrading of the surface, gangrene set in. But for a while amputations were practiced in the hospital almost daily, arising from a gangrenous and scorbutic condition, which, in many cases, threatened the saturation of the whole system with gangrenous or offensive matter, unless the limb was amputated. In cases of amputation of that sort, it would sometimes became necessary to reamputate, from gangrene taking hold of the stump again. Some few successful amputations were made. I recollect two or three which were successful. I kept no statistics; those were kept by the prescription clerks and forwarded to headquarters. I did not think at the time that the surgeon-in-chief did all in his power to relieve the condition of those men, and I made my report accordingly.

In visiting the wards in the morning I would find persons lying dead; sometimes I would find them lying among the living. I recollect on one occasion telling my steward to go and wake up a certain one, and when I went myself to wake him up he was taking his everlasting sleep. That occurred in another man's ward, when I was officer of the day. Upon several occasions, on going into my own wards, I found men whom we did not expect to die, dead from the sensation of chilblains produced during the night. This was in the hospital. I was not so well acquainted with how it was in the stockade. I judge, though, from what I saw, that numbers suffered in the same way there.

The effect of scurvy upon the systems of the men as it developed itself there was the next thing to rottenness. Their limbs would become drawn up. It would manifest itself constitutionally. It would draw them up. They would go on crutches sideways, or crawl upon their hands and knees or on their haunches and feet as well as they could. Some could not eat unless it was something that needed no mastication. Sometimes they would be furnished beef tea or boiled rice, or such things as that would be given them, but not to the extent which I would like to see. In some cases they could not eat corn bread; their teeth would be loose and their gums all bleeding. I have known cases of that kind. I do not speak of it as a general thing. They would ask me to interest myself and get them something which they could swallow without subjecting them to so much pain in mastication. It seemed to me I did express my professional opinion that men died because they could not eat the rations they got.

I cannot state what proportion of the men in whose cases it became necessary to amputate from gangrenous wounds, and also to reamputate from the same cause, recovered. Never having charged my mind on the subject, and not expecting to be called upon in such a capacity, I cannot give an approximate opinion which I would deem reliable. In 1864, amputations from that cause occurred very frequently indeed; during the short time in 1865 that I was there, amputations were not frequent.

The prisoners in the stockade and the hospital were not very well protected from the rain; only by their own meager means, their blankets, holes in the earth, and such things. In the spring of 1865, when I was in the stockade, I saw a shed thirty feet wide and sixty feet long--the sick principally were in that. They were in about the same condition as those in the hospital. As to the prisoners generally, their only means of shelter from the sun and rain were their blankets, if they carried any along with them. I regarded that lack of shelter as a source of disease.

Rice, peas, and potatoes were the common issue from the Confederate government; but as to turnips, carrots, tomatoes, and cabbage, of that class of vegetables, I never saw any. There was no green corn issued. Western Georgia is generally considered a pretty good corn-growing country. Green corn could have been used as an anti-scorbutic and as and antidote. A vegetable diet, so far as it contains any alterative or medical qualities, serves as an anti-scorbutic.

The ration issued to the patients in the hospital was corn meal, beef, bacon - pork occasionally but not much of it; at times, green corn, peas, rice, salt, sugar, and potatoes. I enumerate those as the varieties served out. Potatoes were not a constant ration; at times they were sent in, perhaps a week or two weeks at a time, and then they would drop off. The daily rations was less from the time I went there in September, through October, November, and December, than it was from January till March 26th, the time I left. I never made a calculation as to the number of rations intended for each man; I was never called to do that. So far as I saw, I believe I would feel safe in saying that, while there might have been less, the amount was not over twenty ounces for twenty-four hours.

(3) John L. Ranson, Andersonville Diary (July, 1864)

6th July: Boiling hot, camp reeking with filth, and no sanitary privileges; men dying off over 140 per day. Stockade enlarged, taking in eight or ten more acres, giving us more room, and stumps to dig up for wood to cook with. Jimmy Devers has been a prisoner over a year and, poor boy, will probably die soon. Have more mementos than I can carry, from those who have died, to be given to their friends at home. At least a dozen have given me letters, pictures, etc., to take North. Hope I shan't have to turn them over to someone else.

7th July: Having formed a habit of going to sleep as soon as the air got cooled off and before fairly dark. I wake up at 2 or 3 o'clock and stay awake. I then take in all the horrors of the situation. Thousands are groaning, moaning, and crying, with no bustle of the daytime to drown it.

9th July: One-half the men here would get well if they only had something in the vegetable line to eat. Scurvy is about the most loathsome disease, and when dropsy takes hold with the scurvy, it is terrible. I have both diseases but keep them in check, and it only grows worse slowly. My legs are swollen, but the cords are not contracted much, and I can still walk very well.

10th July: Have bought (from a new prisoner) a large blank book so as to continue my diary. Although it is a tedious and tiresome task, am determined to keep it up. Don't know of another man in prison who is doing likewise. Wish I had the gift of description that I might describe this place.

Nothing can be worse kind of water. Nothing can be worse or nastier than the stream drizzling its way through this camp. And for air to breathe, it is what arises from this foul place. On al four sides of us are high walls and tall tress, and there is apparently no wind or breeze to blow away the stench, and we are obliged to breathe and live in it. Dead bodies lay around all day in the broiling sun, by the dozen and even hundreds, and we must suffer and live in this atmosphere.

12th July: I keep thinking our situation can get no worse, but it does get worse every day, and not less than 160 die each twenty-four hours. Probably one-forth or one-third of these die inside the stockade, the balance in the hospital outside. All day and up to 4 o'clock p.m., the dead are being gathered up and carried to the south gate and placed in a row inside the dead line. As the bodies are stripped of their clothing, in most cases as soon as the breath leaves and in some cases before, the row of dead presents a sickening appearance.

At 4 o'clock, a four or six mule wagon comes up to the gate, and twenty or thirty bodies are loaded onto the wagon and they are carried off to be put in trenches, one hundred in each trench, in the cemetery. It is the orders to attach the name, company, and regiment to each body, but it is not always done. My digging days are over. It is with difficulty now that I can walk, and only with the help of two canes.

(4) Some captured Union Army prisoners in Andersonville began stealing from fellow inmates. Henry Wirz gave instructions for the men to be arrested and tried. John L. Ranson recorded in his diary how six of the men were executed.

This morning, lumber was brought into the prison by the Rebels, and near the gate a gallows erected for the purpose of executing the six condemned Yankees. At about 10 o'clock they were brought inside by Captain Wirtz and some guards. Wirtz then said a few words about their having been tried by our own men and for us to do as we choose with them. I have learned by inquiry their names, which are as follows: John Sarsfield, 144th New York; William Collins, 88th Pennsylvania; Charles Curtiss, 5th Rhode Island Artillery; Pat Delaney, 83rd Pennsylvania; A. Munn, U.S. Navy and W.R. Rickson of the U.S. Navy.

All were given a chance to talk. Munn, a good-looking fellow in Marine dress, said he came into the prison four months before, perfectly honest and as innocent of crime as any fellow in it. Starvation, with evil companions, had made him what he was. He spoke of his mother and sisters in New York, that he cared nothing as far as he himself was concerned, but the news that would be carried home to his people made him want to curse God he had ever been born.

Delaney said he would rather be hung than live here as the most of them lived on the allowance of rations. If allowed to steal could get enough to eat, but as that was stopped had rather hang. He said his name was not Delaney and that no one knew who he really was, therefore his friends would never know his fate, his Andersonville history dying with him.

Curtiss said he didn't care a damn only hurry up and not be talking about it all day; making too much fuss over a very small matter. William Collins said he was innocent of murder and ought not be hung; he had stolen blankets and rations to preserve his own life, and begged the crowd not to see him hung as he had a wife and child at home.

Collins, although he said he had never killed anyone, and I don't believe he ever did deliberately kill a man, such as stabbing or pounding a victim to death, yet he has walked up to a poor sick prisoner on a cold night and robbed him of blanket, or perhaps his rations, and if necessary using all the force necessary to do it. These things were the same as life to the sick man, for he would invariably die.

Sarsfield made quite a speech; he had studied for a lawyer; at the outbreak of the rebellion he had enlisted and served three years in the army, being wounded in battle. Promoted to first sergeant and also commissioned as a lieutenant. He began by stealing parts of rations, gradually becoming hardened as he became familiar with the crimes practised; evil associates had helped him to go downhill.

At about 11 o'clock, they were all blindfolded, hands and feet tied, told to get ready, nooses adjusted, and the plank knocked from under. Munn died easily, as also did Delaney; all the rest died hard, and particularly Sarsfield, who drew his knees nearly to his chin and then straightened them out with a jerk, the veins in his neck swelling out as if they would burst.

Collins' rope broke and he fell to the ground, with blood spurting from his ears, mouth and nose. As they was lifting him back to the swinging-off place, he revived and begged for his life, but no use, was soon dangling with the rest, and died hard.

(5) Edward Kellogg, of the 20th New York Regiment, arrived in Andersonville on 1st March, 1864. He gave evidence at Henry Wirz's trial.

I saw the cripple they called "Chickamauga" shot; he was shot at the south gate. He was in the habit of going off, I believe, to the outside of the gate to talk to officers and the guard, and he wanted to go off this day for something or other. I believe that he was afraid of some of our own men. He went inside the dead-line and asked to be let out. The refused to let him out, and he refused to go outside the dead-line. Captain Wirz came in on his horse and told the man to go outside the dead-line, and went off. After Captain Wirz rode out of the gate the man went inside the dead-line, and Captain Wirz ordered the guard to shoot him, and he shot him. The man lost his right leg, I believe, just above the knee. They called him "Chickamauga." I think he belonged to the Western army and was captured at Chickamauga. I think that was in May. I will not be certain as to the time.

I saw other men shot while I was there. I do not know their names. They were Federal prisoners. The first man I saw shot was shortly after the dead-line was established. I think it was in May. He was shot near the brook, on the east side of the stockade. At that time there was no railing; there was simply posts struck along where they were going to put the dead-line, and this man, in crossing, simply stepped inside one of the posts, and the sentry shot him. He failed to kill him, but wounded him. I don't know his name. I saw a man shot at the brook; he had just come in. He belonged to some regiment in Grant's army. I think this was about the first part of July or the latter part of June. He had just come in and knew nothing about the dead-line. There was no railing across the brook, and nothing to show that there was any such thing as a dead-line there. He came into the stockade, and after he had been shown his place where he was to sleep he went along to the brook to get some water. It was very dark, and a number of men were there, and he went above the rest so as to get better water. He went beyond the dead-line, and two men fired at him and both hit him. He was killed and fell right into the brook. I do not know the man's name. I saw other men shot. I do not know exactly how many. I saw several. It was a common occurrence.

(6) Ole Steensland recalled what it was like when he was released from Andersonville Prison in Georgia (1865)

We were a hard looking bunch. Some of us almost naked, unshaved, with our louse eaten hair hanging down to our shoulders. My ankles were so stiff and my feet so swollen that I could hardly hobble around.

(7) A. G. Blair, who was captured at the battle of the Wilderness gave evidence at Henry Wirz's trial.

Captain Wirz planted a range of flags inside the stockade, and gave the order, just inside the gate, "that if a crowd of two hundred (that was the number) should gather in any one spot beyond those flags and near the gate, he would fire grape and canister into them. I think that the number of men shot during my imprisonment ranged from twenty-five to forty. I do not know that I can give any of their names. I did know them at the time, because they had tented right around me, or messed with me, but their names have slipped my mind. Two of them belonged to the 40th New York Regiment. Those two men were shot just after I got there, in the latter part of June, 1864.

I saw the sentry raise his gun. I shouted to the man. I and several of the rest gave the alarm, but it was to late. Both of these men did not die; one was shot through the arm; the other died; he was shot in the right breast. I did not see Captain Wirz present at the time. I did not hear any orders given to the sentinels, or any words from the sentinels when they fired; nothing more than they often said that it was done by orders from the commandant of the camp, and that they were to receive so many days furlough for every Yankee devil they killed. Those twenty-five or forty men were shot from the middle of June, 1864, until the 1st of September. There were men shot every month. I cannot say that I ever saw Captain Wirz present when any of these men were shot. The majority of those whom I saw shot were killed outright; expired in a few moments.

(8) Robert E. Lee was cross-examined by Jacob Howard, the senator from Michigan, as a Congressional committee held on 17th February, 1866. Howard questioned Lee about what happened at Andersonville Prison Camp.

I suppose they suffered from want of ability on the part of the Confederate States to supply them with their wants. At the very beginning of the war there was suffering of prisoners on both sides, but as far as I could I did everything in my power to establish the cartel (of prisoner exchange) as agreed upon. I made several efforts to exchange the prisons after the cartel was suspended. I offered to General Grant, around Richmond, that we should ourselves exchange all the prisoners in our hands. I offered to send to City Point all the prisoners in Virginia and North Carolina over which my command extended, provided they returned an equal number of mine, man for man. I reported this to the War Department, and received an answer that they could place at my command all the prisoners at the South if the proposition was accepted. I heard nothing more on the subject.