Clem Beckett

Clem Beckett was born in Oldham in 1906. After leaving school he became a blacksmith. He also became a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain. According to Graham Stevenson: "His trade was of a blacksmith but, faced with victimisation and depression after the late 1920s, he started riding the Dome of Death at fairgrounds. So, stunning and confident was his mastery of this feat that, in no short time he had became famous as Dare Devil Beckett, the man who rode the Wall of Death and who broke world records."

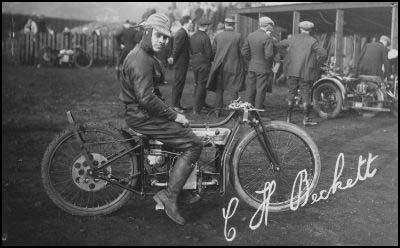

Beckett became a speedway rider for White City, a team based in London. According to David Hallam: "When speedway was first introduced to this country many greyhound stadium owners jumped on the bandwagon. Young kids were persuaded to race irrespective of their experience and many were killed or seriously injured. Clem Beckett... played a major part in setting up a trades union for riders that stopped this lethal exploitation." George Sinfield later commented: "Beneath his leather jacket beat a heart of gold. It was a heart that throbbed in rhythm with the struggle of the working people."

Jon Tait recently wrote on The Morning Star website: "Clem Beckett loved the dirty growl of his bike's engine, the smell of diesel and hot metal filling his nostrils. An enduring image for those lucky enough to see him ride was of the legendary speedway star zipping around the final corner before crossing the finish line, muck spraying up from his back tyre before he lifted his goggles, his face flecked with mud as he celebrated another win. Beckett loved the thrill of the speedway track, the rush of adrenaline as the back end of his ride slipped out, gunning the throttle and feeling the cool blast of wind in his face... The racetrack owners must have regarded Beckett as a bit of a rebel - he unionised the sport when he formed the Dirt-track Riders Association."

On 30th March 1929, Beckett joined forces with Spencer Stratton and Jimmy Hindle to establish the Sheffield Tigers. As Graham Stevenson points out: "Operating as Provincial Dirt-Tracks Ltd, the group had sunk their savings into buying land at Owlerton Meadows. Since the sport was then sweeping the country, it was perhaps not such a risky venture in retrospect but many thought not at the time. It was so new that it was only the fifth such venture in the country. Beckett now shone as the star of the new Owlerton Stadium, winning the golden helmet in front of 15,000 spectators, whereas even with a renaissance in the sport only a few thousand would now turn out."

In 1932 Clem Beckett was active in the campaign to gain access to open spaces in what is now the Peak District National Park. In 1932 he took part in what became known as the Kinder Trespass. Joseph Norman was one of those activists who worked alongside Beckett: "My first real experience of political activity was the mass trespass on Kinder Scout in Derbyshire which eventually led to the designation of the area as a National Park. Dozens of those that fought the police and landowners on that mass trespass were... men like Clem Beckett and George Brown."

According to Martin Rogers, the author of The Illustrated History of Speedway, Beckett, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, took a tour party to the Soviet Union in 1932. Despite the best efforts of Beckett, "there was no real speedway development there" until after the Second World War.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, the Communist Party of Great Britain helped establish the International Brigades. Clem Beckett was one of several members of the Manchester branch of the CPGB who volunteered to go to Spain to defend the Popular Front government. Maurice Levine later recalled: "One of the prime factors in me making an application to go to Spain was that Eddie Swindell, a glass worker friend of mine, was very friendly with Arnold Jeans who had already gone to Spain with Clem Beckett."

After failing to take Madrid by frontal assault General Francisco Franco gave orders for the road that linked the city to the rest of Republican Spain to be cut. A Nationalist force of 40,000 men, including men from the Army of Africa, crossed the Jarama River on 11th February, 1937.

General José Miaja sent three International Brigades including the Dimitrov Battalion and the British Battalion to the Jarama Valley to block the advance. Jason Gurney pointed out in his book, Crusade in Spain (1974): "I got back to Wintringham's HQ and relayed the Brigadier's orders. Runners were sent out to 1, 3 and 4 Companies to order the advance. I went up to No. 2 Company's trench to observe their movement and report back. William Briskey's No. 3 Company on the Casa Blanca hill was the first to move down the hill from its summit, followed shortly after by No. 1 Company under Kit Conway." Clem Beckett wrote to his wife from the front-line at Jarama: "I'm sure you'll realise that I should never have been satisfied had I not assisted. Only my hatred of Fascism brought me here." William Rust, the author of Britons in Spain (1939): "Even the bravest would have shuddered as they took up position in the morning, had they known what the day had in store for them."

Clem Beckett and his friend Christopher Caudwell, took control of a Charcot light machine-gun. On 12th February, 1937, at what became known as Suicide Hill, the Republicans suffered heavy casualties. Hugh Thomas, the author of The Spanish Civil War (1961) has commented: "A mere two hundred and twenty-five out of the original six hundred members of the British Battalion were left at the end of the day." Beckett's friend, George Sinfield, later pointed out: "Clem and Chris were posted at a vital point. They faced innumerable odds: artillery, planes, and howling Moors throwing hand-grenades. Their section was ordered to retire. Clem and Chris kept their machine-gun trained on the advancing fascists, as a cover to the retreat. The advance was halted, but Clem and Chris... lost their lives."

Primary Sources

(1) Jon Tait, Clem Beckett: Star of the Speedway Track (30th June, 2009)

Clem Beckett loved the dirty growl of his bike's engine, the smell of diesel and hot metal filling his nostrils. An enduring image for those lucky enough to see him ride was of the legendary speedway star zipping around the final corner before crossing the finish line, muck spraying up from his back tyre before he lifted his goggles, his face flecked with mud as he celebrated another win.

Beckett loved the thrill of the speedway track, the rush of adrenaline as the back end of his ride slipped out, gunning the throttle and feeling the cool blast of wind in his face.

The 1930s racing star felt exhilirated by the feeling of speed, only vaguely aware of the roar of the crowd, lost in the bubble that sportsmen know as "the zone."

The racetrack owners must have regarded Beckett as a bit of a rebel - he unionised the sport when he formed the Dirt-track Riders Association.

And then, in 1936, the great British rider from Oldham swapped greasing parts of his engine with an oily rag for lubricating a rifle with olive oil as he went out to Spain to fight for democracy in the international brigades.

Clem Beckett, his face, uniform and rifle powdered with the yellow dust which blew up from the Spanish plains, was one of around 500 men who took part in the British Battalion's action at Jarama in February 1937.

Indeed, Beckett's last days were as hair-raising as those that he spent on the racetrack.

The world-famous rider and his comrades climbed out of a truck at a farmhouse by the side of the road and had bread and coffee, filled their metal canteens and checked their weapons.

Up the dusty road, rust-red hills and ridges climbed to a plateau covered in olive trees and the glint of the Jarama River wound its way through the valley at the other side.

The British Battalion advanced up through the rocky, loose ground and, as they began to scramble down the slopes towards the glittering river, came under heavy fire from the forces of fascist General Franco.

Their ears were full of the noise of the rattle of small arms and the high-pitched zip of rounds flashing past and kicking up little clouds of dust with a dull thump. Heavier machine-gun bursts thumped around the valley.

Beckett shouldered his rifle and began returning fire, empty brass cases flying out and scattering the ground around him. Men began falling, spinning as they were strafed by the German-made guns.

The stench of cordite hung heavy in the air and the shouting of soldiers was drowned by muzzle flashes around the hillside.

Under a constant, relentless barrage by a much larger and better-equipped force, the British held their position at Suicide Hill for seven hours. But at a high cost - 275 of the 400 men in the Rifle Company were killed in the first day of the battle, which would rage for three days. Clem Beckett, the speedway legend - a true sporting hero - was one of them. His engine had finally fallen silent.

(2) William Rust, Britons in Spain (1939)

The 15th Brigade did not go into action until February 12th, six days after the launching of the Fascist offensive. The day before, the enemy had succeeded in crossing the Jarama river with ten thousand troops, equipped with tanks and artillery, and were thrusting three columns towards the Valencia road, one directed against Vacia-Madrid and the other two against Arganda and Morata respectively. The decisive hours in the fight for the Madrid-Valencia Road had begun and the Republican command had to fling all available troops into action. The 15th Brigade was ordered to take position between two of the advancing Fascist columns, those aiming for Morata and Arganda.

Even the bravest would have shuddered as they took up position in the morning, had they known what the day held in store for them. Six hundred Britishers, under Captain Tom Wintringham, started out in lorries from Chinchon on that raw February morning, but by nightfall there were not more than three hundred men in the ranks. All day long they fought, desperately searching for cover in furrows and streams, behind olive trees, shrubs and vines while a well-armed enemy sent over an avalanche of steel. All day long they answered back with old guns and rifles. All day long they held their ground and were not afraid, though the bullets buzzed around them like a thousand bees; fear was not felt because in such a hell it was no use being afraid. And then when they retreated at sunset these exhausted, wounded, blood-stained men disputed every yard of the way with their red-hot rifles and dragged their heavy machine guns into action against the enemy until the advance was stemmed. The first day of the British Battalion's first action is a story not even surpassed by those later battles when the men had become hardened and war experienced.

(3) George Sinfield, Challenge (15th April, 1950)

I knew Clem well. He stayed with me when visiting London. Beneath his leather jacket beat a heart of gold. It was a heart that throbbed in rhythm with the struggle of the working people. When news of his death reached speedway fans, they saw their idol in a new role. When Clem joined the International Brigade, he chummed up with a young poet and novelist, Christopher Sprigg (Caudwell). The friendship of the sturdy, keen-witted sportsman with the quiet intellectual was one of the most moving incidents in the struggle for Spain. They died together. They sacrificed their lives during the epic battle of Arganda Bridge on February 12, 1937. Clem and Chris were posted at a vital point. They faced innumerable odds: artillery, planes, and howling Moors throwing hand-grenades. Their section was ordered to retire. Clem and Chris kept their machine-gun trained on the advancing fascists, as a cover to the retreat. The advance was halted, but Clem and Chris... lost their lives."

(4) Graham Stevenson, Clem Beckett (15th April, 1950)

The then relatively new sport of speedway motorcycle racing was massively popular amongst young working class people in the 1930s. It is diffcult to imagine quite how much so; but, arguably, Clem Beckett was the David Beckham of his day. Young men aspired to his skill and daring and young women swooned over his dashing appearance!

Beckett's machine gun jammed as he was trying to keep open the Valencia-Madrid road, with the result that the position was overwhelmed by Fascist troops and he and all of his comrades were wiped out. Clem's death was front page news in some cities in Britain and many were surprised that he had even gone to fight in Spain. There's a sense in which Beckett is more representative of the daring young men of the International Brigades than the false image of pale poets that is sometimes offered up. Working class young men in the wake of the General Strike and mass unemployment did surprising things, not only to make a living but somehow the very drama of the times made for great sacrifices, too.