Rirette Maitrejean

Rirette Maitrejean (Anna Estorges) was born in Tulle in 1887. She wanted to be a teacher but her father died in 1903 and she had to abandon the idea. Rirette rejected her mother's plans for an arranged marriage and fled to Paris where she associated with a group of anarchists led by Albert Libertad.

Rirette believed in free love and gave birth to two children before marrying Louise Maitrejean in 1906. She later left Maitrejean to live with Maurice Vandamme. In July 1908 she was seriously wounded in the leg when police opened fire on demonstrators. Four men were killed and another 200 were wounded.

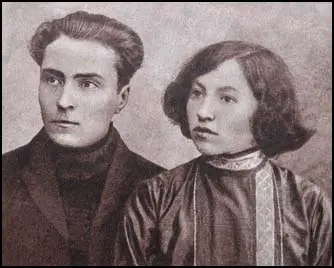

In 1909 she met Victor Serge in Lille. He described her as "short, slim, agressive girl, militant, with a Gothic profile". They fell in love and they lived together in Paris. Serge recalled how he worked as "a draughtsman in a machine-tool works, ten hours a day, twelve and a half including the journeys, starting at 6:30 a.m." After the death of Albert Libertad in a street-fight, the couple helped to edit l'Anarchie.

The execution of the non-violent anarchist, Francisco Ferrer in Barcelona on 13th October, 1909, had a profound impact on Rirette. Serge wrote: "His transparent innocence, his educational activity, his courage as an independent thinker, and even his man-in-the-street appearance endeared him infinitely to the whole of a Europe that was, at the time, liberal by sentiment and in intense ferment. A true international consciousness was growing from year to year, step by step with the progress of capitalist civilization.... From one end of the Continent to the other (except in Russia and Turkey) the judicial murder of Ferrer had, within twenty-four hours, moved whole populations to incensed protest."

One of their friends, Liabeuf, a young worker of twenty, armed himself with a revolver and open fire on the police. He wounded four policeman and after being found guilty of attempted murder, was condemned to death. It was decided to execute him at the Boulevard Arago. Serge recalled in Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "I had come with Rirette... The militants from all the groups were there, forced back by walls of black-uniformed police executing bizarre maneuvers. Shouts and angry scuffles broke out when the guillotine wagon arrived, escorted by a squad of cavalry. For some hours there was a battle on the spot, the police charges forcing us ineffectively, because of the darkness, into side streets from which sections of the crowd would disgorge once again the next minute."

Jules Bonnot arrived in Paris in 1911. According to Serge: "From the grapevine we gathered that Bonnot... had been traveling with him by car, had killed him, the Italian having first wounded himself fumbling with a revolver." Bonnot soon formed a gang that included local anarchists, Raymond Callemin, André Soudy, Stephen Monier, Octave Garnier, René Valet and Edouard Carouy. Serge was totally opposed to what the group intended to do. Callemin visited Serge when he heard what he had been saying: "If you don't want to disappear, be careful about condemning us. Do whatever you like! If you get in my way I'll eliminate you!" Serge replied: "You and your friends are absolutely cracked and absolutely finished."

On 21st December, 1911 the gang robbed a messenger of the Société Générale Bank in broad daylight and then fled in a car. As Peter Sedgwick pointed out: "This was an astounding innovation when policemen were on foot or bicycle. Able to hide, thanks to the sympathies and traditional hospitality of other anarchists, they held off regiments of police, terrorized Paris, and grabbed headlines for half a year."

The police raided the offices of l'Anarchie on 31st December, 1911. Louis Jouin, the vice-chief of the French police, told Serge: "I know you pretty well; I should be most sorry to cause you any trouble-which could be very serious. You know these circles, these men, who are very unlike you, and would shoot you in the back, basically.... they are all absolutely finished. I can assure you. Stay here for an hour and we'll discuss them. Nobody will ever know anything of it and I guarantee that there'll be no trouble at all for you." Serge and Rirette Maitrejean refused to help them and they were arrested and accused of being part of the Jules Bonnot gang. The main evidence consisted of two revolvers found on the premises of the newspaper. They spent the next fifteen months in solitary confinement.

The gang murdered a police officer at the Place du Havre on 27th February, 1912. The following month, on 25th March, two more people were killed during an attack on the office of the General Corporation in Chantilly. Serge complained in Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951): "A positive wave of violence and despair began to grow. The outlaw anarchists shot at the police and blew out their own brains. Others, overpowered before they could fire the last bullet into their own heads, went off sneering to the guillotine.... I recognized, in the various newspaper reports, faces I had met or known; I saw the whole of the movement founded by Libertad dragged into the scum of society by a kind of madness; and nobody could do anything about it, least of all myself. The theoreticians, terrified, headed for cover. It was like a collective suicide."

Raymond Callemin was arrested on 7th April, 1912, Seventeen days later, three policemen surprised Jules Bonnot in the apartment of a man known to buy stolen goods. He shot at the officers, killing Louis Jouin, the vice-chief of the French police, and wounding another officer before fleeing over the rooftops. Four days later he was discovered in a house in Choisy-le-Roi. It is claimed the building was surrounded by 500 armed police officers, soldiers and firemen. Bonnot was able to wound three officers before the house before the police used dynamite to demolish the front of the building. In the battle that followed Bonnott was shot ten times. He was moved to the Hotel-Dieu de Paris before dying the following morning. Octave Garnier and René Valet were killed during a police siege of their suburban hideout on 15th May, 1912.

The trial of Maitrejean, Serge, Raymond Callemin, Jean de Boe, Rirette Maitrejean, Edouard Carouy, André Soudy, Eugène Dieudonné, and Stephen Monier, began on 3rd February, 1913. According to Serge: "In the course of a month, 300 contradictory witnesses paraded before the bar of the court. The inconsequently of human testimony is astonishing. Only one in ten can record more or less clearly what they have seen with any accuracy, observe, and remember - and then be able to recount it, resist the suggestions of the press and the temptations of his own imagination. People see what they want to see, what the press or the questioning suggest."

Callemin, Soudy, Dieudonné and Monier were sentenced to death. When he heard the judge's verdict, Callemin jumped up and shouted: "Dieudonné is innocent - it's me, me that did the shooting!" Carouy was sentenced to hard labour for life (he committed suicide a few days later). Serge received five years' solitary confinement but Maitrejean was acquitted. Dieudonné was reprieved but Callemin, Soudy and Monier were guillotined at the gates of the prison on 21st April, 1913.

Maitrejean married Serge in prison in 1915 in order to have the right to visit and correspond. She worked as printer for various anarchist publications. After her divorce from Victor Serge she lived with Maurice Merle (an active trade unionist of the Renault factories) and wrote for the La Revue Anarchiste. She ceased political activity when she went blind in 1959.

Rirette Maitrejean died in Limeil-Brévannes on 14th June 1968.

Primary Sources

(1) Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1951)

The end of 1911 saw dramatic happenings. Joseph the Italian, a little militant with frizzled hair who dreamed of a free life in the bush of Argentina, as far away as possible from the towns, was found murdered on the Melun Road. From the grapevine we gathered that an individualist from Lyons, Bonnot by name (I did not know the man), who had been traveling with him by car, had killed him, the Italian having first wounded himself fumbling with a revolver. However it may have happened, one comrade had murdered or "done" another. An informal investigation shed no light on the matter and only annoyed the "scientific" illegalists. Since I had expressed hostile opinions towards them, I had an unexpected visit from Raymond. "If you don't want to disappear, be careful about condemning us." He added, laughingly, "Do whatever you like! If you get in my way I'll eliminate you!"

"You and your friends are absolutely cracked," I replied, "and absolutely finished." We faced each other exactly like small boys over a red cabbage. He was still squat and strapping, baby-faced and merry. "Perhaps that's true," he said, "but it's the law of nature."

A positive wave of violence and despair began to grow. The outlaw anarchists shot at the police and blew out their own brains. Others, overpowered before they could fire the last bullet into their own heads, went off sneering to the guillotine. "One against all!" "Nothing means anything to me!" "Damn the masters, damn the slaves, and damn me!" I recognized, in the various newspaper reports, faces I had met or known; I saw the whole of the movement founded by Libertad dragged into the scum of society by a kind of madness; and nobody could do anything about it, least of all myself. The theoreticians, terrified, headed for cover. It was like a collective suicide. The newspapers put out a special edition to announce a particularly daring outrage, committed by bandits in a car on the Rue Ordener in Montmartre, against a bank cashier carrying half a million francs. Reading the descriptions, I recognized Raymond and Octave Garnier, the lad with piercing black eyes who distrusted intellectuals. I guessed the logic of their struggle: in order to save Bonnot, now hunted and trapped, they had to find either money, money to get away from it all, or else a speedy death in this battle against the whole of society. Out of solidarity they rushed into this squalid, doomed struggle with their little revolvers and their petty, trigger-happy arguments. And now there were five of them, lost, and once again without money even to attempt flight, and against them towered Money - 100,000 francs' reward for the first informer.