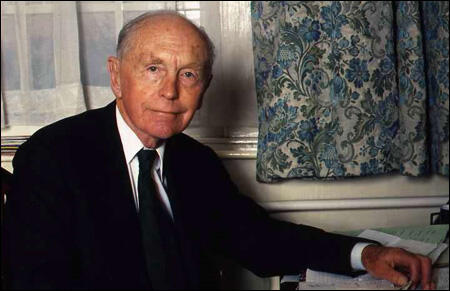

Alec Douglas-Home

Alec Douglas-Home, the son of the 13th Earl of Home, was born in London on 2nd July, 1903. Educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, he joined the Conservative Party and was elected to the House of Commons in the 1931 General Election.

Douglas-Home served as parliamentary private secretary to Neville Chamberlain and was involved in the negotiations with Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini between 1937 and 1939.

During the Second World War Douglas-Home spent time in hospital as a result of a spinal operation. He lost his seat in the 1945 General Election but returned to the House of Commons in 1950. The following year, on the death of his father, he became the 14th Earl of Home.

In 1951 Winston Churchill appointed him as Minister of State at the Scottish Office. He held the post for six years before Anthony Eden made him Commonwealth Relations Secretary (1955-1960), Lord President of the Council (1957-1960) and Foreign Secretary (1960-63). During this period he also served as leader of the House of Lords.

When Harold Macmillan resigned in October, 1963, the Earl of Home became prime minister. He immediately resigned his peerage and won a by-election at Kinross and Western Perthshire. A year later the Conservative Party was defeated at the 1964 General Election and Harold Wilson became the new prime minister.

Edward Heath replaced Douglas Home as leader of the Conservative Party in July 1965. After the 1974 General Election Douglas-Home served as Foreign Secretary in Heath's government.

In 1974 he was granted the title Baron Home of the Hirsel of Coldstream. His autobiography, The Way the Wind Blows, was published in 1976. Other books included Border Reflections (1979) and Letters to a Grandson (1983).

Alec Douglas Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel of Coldstream, died in Berwickshire, Scotland, on 9th October, 1995.

Primary Sources

(1) Margaret Thatcher, The Path to Power (1995)

Douglas-Home was a manifestly good man - and goodness is not to be underrated as a qualification for those considered for powerful positions. He was also in the best possible way 'classless'. You always felt that he treated you not as a category but as a person. And he actually listened - as I found when I took up with him the vexed question of the widowed mothers' allowance.

But the press were cruelly, ruthlessly and almost unanimously against him. He was easy to caricature as an out-of-touch aristocrat, a throwback to the worst sort of reactionary Toryism. Inverted snobbery was always to my mind even more distasteful than the straightforward self-important kind. By 1964 British society had entered a sick phase of liberal conformism passing as individual self-expression. Only progressive ideas and people were worthy of respect by an increasingly self-conscious and self-confident media class. And how they laughed when Alec said self-deprecatingly that he used matchsticks to work out economic concepts. What a contrast with the economic models with which the technically brilliant mind of Harold Wilson was familiar.

(2) Harold Wilson, Memoirs: The Making of a Prime Minister, 1916-64 (1986)

The Tories should have elected Rab Butler to succeed him. I expected them to do so and I would have enjoyed renewing the contest of the 1950s. But Rab did not have enough of the killer instinct to take over and his colleagues knew it. Instead, they chose the Earl of Home, who demoted himself to the House of Commons for the purpose. Politically I was pleased. Instead of the formidable Macmillan, with his deep knowledge of politics and administration, I was getting an opponent with very little experience of Parliament and much ignorance of economics.

He was to prove much more formidable than I expected. When the election came we only just scraped in and I am often asked whether we might have lost if Macmillan had been restored to power. It is very hard to say, but I doubt it. Macmillan had provided us with so much ammunition that I consider that we would have made mincemeat of him, whereas with Alec Douglas-Home our barrage was perhaps more subdued.

(3) Edward Heath, The Course of My Life (1988)

It is sometimes suggested that I helped to engineer Alec Douglas-Home's path to No. 10 for entirely selfish reasons, because I knew that he would lose the election and prove to be only a stop-gap, enabling me to become leader. In fact, I sincerely believed in 1963 that Alec was the only candidate capable of uniting the party. After the fuss caused by Macleod had died down, that is exactly what he succeeded in doing. Of course it is true that, had a younger candidate from my own generation succeeded Macmillan in 1963, it would obviously have been impossible for me to become leader when I did. But politics is an unpredictable business, and it would have been madness for me to assume anything about the longer-term at that stage. Moreover, Alec was a highly perceptive and shrewd politician and, had I really been playing such a game, he would have seen straight through me and would never have given me the responsibilities that he did between November 1963 and July 1965, nor would he have agreed to be my shadow Foreign Secretary after I replaced him as leader.