1884 Reform Act

The 1880 General Election was won by William Gladstone and the Liberal Party that had successfully obtained 352 seats with 54.7% of the vote. The party had gained from an increase in the number of working-class male voters. As Paul Foot has pointed out, this was not reflected in the newly formed government: "In the Cabinet of fourteen members, there were six earls (Selborne, Granville, Derby, Kimberley, Northbrook and Spencer), a marquis (Hartington), a baron (Carlingford), two baronets (Harcourt and Dilke) and only four commoners (Gladstone, Childers, Dodson and Joseph Chamberlain)." Only one working man, the trade union leader, Henry Broadhurst, joined the government as a junior minister for trade. (1)

Queen Victoria and Gladstone were in constant conflict during his premiership. She often wrote to him complaining about his progressive policies. When he became prime minister in 1880 she warned him about the appointment of Radicals such as Joseph Chamberlain, Charles Wentworth Dilke, Henry Fawcett, James Stuart, Thorold Rogers and Anthony Mundella, The Queen was also disappointed that Gladstone had not found a place for George Goschen, in his government, a man who she knew was strongly against parliamentary reform. (2)

Conservative Party and Parliamentary Reform

Queen Victoria was especially opposed to parliamentary reform. In November, 1880, Queen Victoria she told him that he should be careful about making statements about future political policy: "The Queen is extremely anxious to point out to Mr. Gladstone the immense importance of the utmost caution on the part of all the Ministers but especially of himself, at the coming dinner in the City. There is such danger in every direction that a word too much might do irreparable mischief." (3) The following year she made a similar comment: "I see you are to attend a great banquet at Leeds. Let me express a hope that you will be very cautious not to say anything which could bind you to any particular measures." (4)

Philip Guedalla, the author of The Queen and Mr. Gladstone (1958), has pointed out: "The tragedy of Queen Victoria's relations with Mr. Gladstone was a tragedy of growth. Time and growth altered both of them... Such changes are inevitable, and they might both have aged together without uncomfortable consequences. But unhappily the processes of growth took them in opposite directions, and they grew away from one another. As the years went by, Gladstone moved steadily towards the Left in politics, while by a sad mischance his soverign inclined towards the Right. Worse still, Gladstone did not stop growing... Mr. Gladstone continued to grow visibly more Radical." (5)

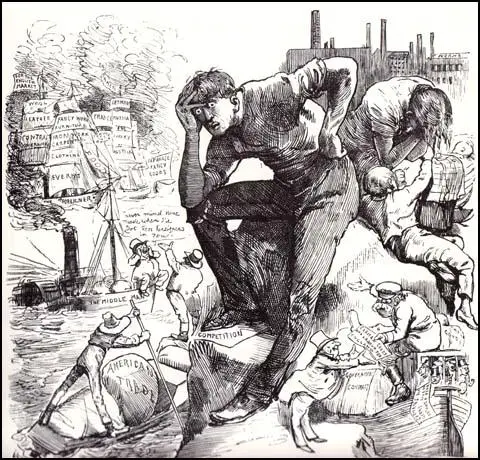

William Gladstone, but not most of his cabinet, was committed to parliamentary reform. The 1867 Reform Act had granted the vote to working class males in the towns but not in the counties. Gladstone argued that people living in towns and in rural areas should have equal rights. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, leader of the Conservative Party, opposed any increase in the number of people who could vote in parliamentary elections. Salisbury's critics claimed that he feared that this reform would reduce the power of the Tories in rural constituencies. (6)

John Eldon Gorst, the Conservative MP for Chatham, disagreed with Salisbury about all resistance to change. "Unfortunately for Conservatism, its leaders belong solely to one class; they are a clique composed of members of the aristocracy, land-owners, and adherents whose chief merit is subserviency. The party chiefs live in an atmosphere in which a sense of their own importance and of the importance of their class interests and privileges is exaggerated, and to to which the opinions of the common people can scarcely penetrate.... If the Tory party is to continue to exist as a power in the State, it must become a popular party... The days are past when an exclusive class, however great its ability, wealth, and energy, can command a majority in the electorate." (7)

In 1884 William Gladstone introduced his proposals that would give working class males the same voting rights as those living in the boroughs. The bill faced serious opposition in the House of Commons. The Tory MP, William Ansell Day, argued: "The men who demand it are not the working classes... It is the men who hope to use the masses who urge that the suffrage should be conferred upon a numerous and ignorant class." (8)

Gladstone told the House of Commons "that every Reform Bill had improved the House as a Representative Assembly". When opponents of the proposed bill cried "No, no !" Gladstone "insisted that whatever might be the effect on the House from some points of view, it was past doubt that the two Reform Acts had made the House far more adequate to express the wants and wishes of the nation as a whole". He added that when the House of Lords had blocked the Liberal's 1866 Reform Bill the following year "the Conservatives found it absolutely necessary to deal with the question, and so it would be again". (9)

Votes for Women

Left-wing members of the Liberal Party, such as James Stuart, urged Gladstone to give the vote to women. Stuart wrote to Gladstone's daughter, Mary Gladstone Drew: "To make women more independent of men is, I am convinced, one of the great fundamental means of bringing about justice, morality, and happiness both for married and unmarried men and women. If all Parliament were like the three men you mention, would there be no need for women's votes? Yes, I think there would. There is only one perfectly just, perfectly understanding Being - and that is God.... No man is all-wise enough to select rightly - it is the people's voice thrust upon us, not elicited by us, that guides us rightly." (10)

A total of 79 Liberal MPs asked Gladstone to recognize the claim of women's householders to the vote. Gladstone replied that if votes for women was included Parliament would reject the proposed bill: "The question with what subjects... we can afford to deal in and by the Franchise Bill is a question in regard to which the undivided responsibility rests with the Government, and cannot be devolved by them upon any section, however respected , of the House of Commons. They have introduced into the Bill as much as, in their opinion, it can safely carry." (11)

Queen Victoria strongly expressed herself to Gladstone against this "mad folly of Women's Rights." (12) Gladstone authorized his Chief Whip to tell Liberal MPs that if the votes-for-women amendment were carried the bill would be dropped and the government would resign. He explained that "I am myself not strongly opposed to every form and degree of the proposal, but I think that if put into the Bill it would give the House of Lords a case for postponing it and I know not how to incur such a risk." (13)

Gladstone and the House of Lords

George Goschen had been one of the leading Liberal opponents to the 1867 Reform Act. However, he supported the 1884 Reform Act: "The argument against the enfranchisement of the working class was this - and no doubt it is a very strong argument - the power they would have in any election if they combined together on questions of class interest. We are bound not to put that risk out of sight. Well, at the last election, I carefully watched the various contests that were taking place and I am bound to admit that I saw no tendency on the part of the working classes to combine on any special question where their pecuniary interests were concerned. On the contrary, they seemed to me to take a genuine political interest in public questions ... The working classes have given proofs that they are deeply desirous to do what is right." (14)

The bill was passed by the Commons on 26th June, with the opposition did not divide the House. The Conservatives were hesitant about recording themselves in direct hostility to franchise enlargement. However, Gladstone knew he would have more trouble with the House of Lords. Gladstone wrote to twelve of the leading bishops and asked for their support in passing this legislation. Ten of the twelve agreed to do this. However, when the vote was taken the Lords rejected the bill by 205 votes to 146.

Queen Victoria thought that the Lords had every right to reject the bill and she told Gladstone that they represented "the true feeling of the country" better than the House of Commons. Gladstone told his private secretary, Edward Walter Hamilton, that if the Queen had her way she would abolish the Commons. Over the next two months the Queen wrote sixteen letters to Gladstone complaining about speeches made by left-wing Liberal MPs. (15)

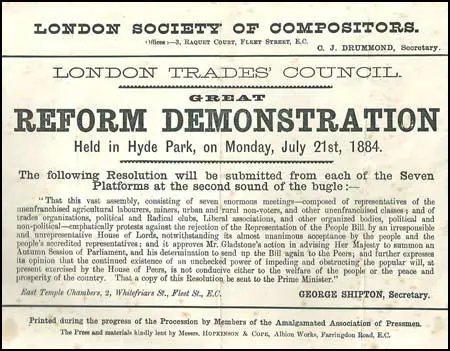

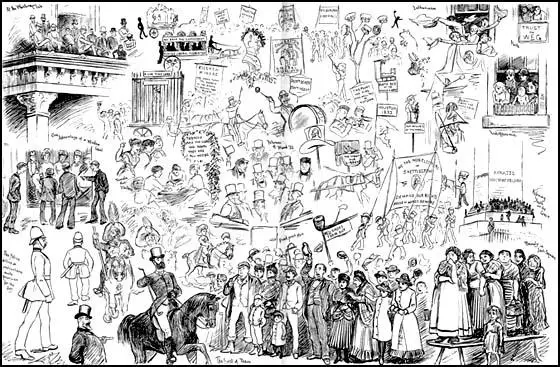

The London Trades Council quickly organized a mass demonstration in Hyde Park. On 21st July, an estimated 30,000 people marched through the city to merge with at least that many already assembled in the park. Thorold Rogers, compared the House of Lords to "Sodom and Gomorrah" and Joseph Chamberlain told the crowd: "We will never, never, never be the only race in the civilized world subservient to the insolent pretensions of a hereditary caste". (16)

Queen Victoria was especially angry about the speech made by Chamberlain, who was President of the Board of Trade in Gladstone's government. She sent letters to Gladstone complaining about Chamberlain on 6th, 8th and 10th August, 1884. (17) Edward Walter Hamilton, Gladstone's private secretary replied to the Queen explaining that the Prime Minister "has neither the time nor the eyesight to make himself acquainted by careful perusal with all the speeches of his colleagues." (18)

In August 1884, William Gladstone sent a long and threatening memorandum to the Queen: "The House of Lords has for a long period been the habitual and vigilant enemy of every Liberal Government... It cannot be supposed that to any Liberal this is a satisfactory subject of contemplation. Nevertheless some Liberals, of whom I am one, would rather choose to bear all this for the future as it has been borne in the past, than raise the question of an organic reform of the House of Lords... I wish (an hereditary House of Lords) to continue, for the avoidance of greater evils... Further; organic change of this kind in the House of Lords may strip and lay bare, and in laying bare may weaken, the foundations even of the Throne." (19)

Other politicians began putting pressure on Victoria and the House of Lords. One of Gladstone's MPs advised him to "Mend them or end them." However, Gladstone liked "the hereditary principle, notwithstanding its defects, to be maintained, for I think it in certain respects an element of good, a barrier against mischief". Gladstone was also secretly opposed to a mass creation of peers to give it a Liberal majority. However, these threats did result in conservative leaders being willing to negotiate over this issue. Hamilton wrote in his diary that "the atmosphere is full of compromise". (20)

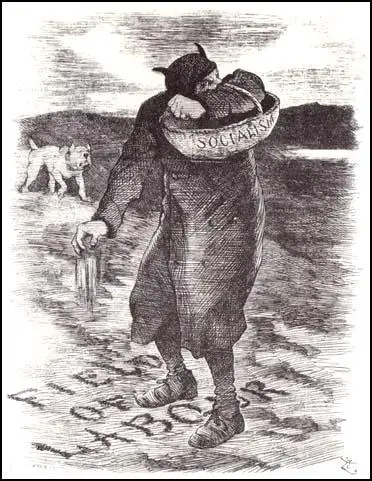

Other moderate Liberal MPs feared that if the 1884 Reform Act was not passed Britain was in danger of a violent revolution. Samuel Smith feared the development of socialist parties such as the Social Democratic Party in Germany: "In the country, the agitation has reached a point which might be described as alarming. I have no desire to see the agitation assume a revolutionary character which it would certainly assume if it continued much longer.... I am afraid that there would emerge from out of the strife a new party like the social democrats of Germany and that the guidance of parties would pass from the hands of wise statesmen into that of extreme and violent men". (21)

John Morley was one of the MPs who led the fight against the House of Lords. The Spectator reported "He (John Morley) was himself, be said, convinced that compromise was the life of politics; but the Franchise Bill was a compromise, and if the Lords threw it out again, that would mean that the minority were to govern... The English people were a patient and a Conservative people, but they would not endure a stoppage of legislation by a House which had long been as injurious in practice as indefensible in theory. If the struggle once began, it was inevitable that the days of privilege should be numbered." (22)

1884 Reform Act

Eventually, Gladstone reached an agreement with the House of Lords. This time the Conservative members agreed to pass Gladstone's proposals in return for the promise that it would be followed by a Redistribution Bill. Gladstone accepted their terms and the 1884 Reform Act was allowed to become law. This measure gave the counties the same franchise as the boroughs - adult male householders and £10 lodgers - and added about six million to the total number who could vote in parliamentary elections. (23)

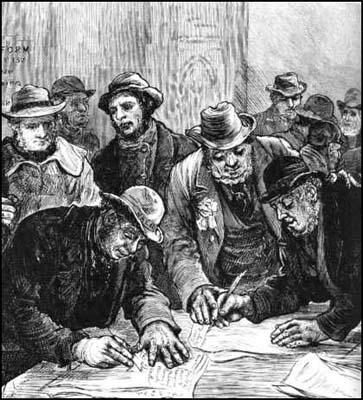

However, this legislation meant that all women and 40% of adult men were still without the vote. According to Lisa Tickner: "The Act allowed seven franchise qualifications, of which the most important was that of being a male householder with twelve months' continuous residence at one address... About seven million men were enfranchised under this heading, and a further million by virtue of one of the other six types of qualification. This eight million - weighted towards the middle classes but with a substantial proportion of working-class voters - represented about 60 per cent of adult males. But of the remainder only a third were excluded from the register of legal provision; the others were left off because of the complexity of the registration system or because they were temporarily unable to fulfil the residency qualifications... Of greater concern to Liberal and Labour reformers... was the issue of plural voting (half a million men had two or more votes) and the question of constituency boundaries." (24)

Primary Sources

(1) John Eldon Gorst, The Fortnightly Review (August, 1882)

If the Tory party is to continue to exist as a power in the State, it must become a popular party. A mere coalition with the Whig aristocracy might delay, but could not avert its downfall. The days are past when an exclusive class, however great its ability, wealth, and energy, can command a majority in the electorate. The liberties and interests of the people at large are the only things which it is now possible to conserve: the rights of property, the Established Church, the House of Lords, and the Crown itself must be defended on the ground that they are institutions necessary or useful to the preservation of civil and religious liberty and securities for personal freedom, and can be maintained only so far as the people take this view of their subsistence. Unfortunately for Conservatism, its leaders belong solely to one class; they are a clique composed of members of the aristocracy, land-owners, and adherents whose chief merit is subserviency. The party chiefs live in an atmosphere in which a sense of their own importance and of the importance of their class interests and privileges is exaggerated, and to which the opinions of the common people can scarcely penetrate. They are surrounded by sycophants who continually offer up the incense of personal flattery under the pretext of conveying political information. They half fear and half despise the common people, whom they see only through this deceptive medium; they regard them more as dangerous allies to be coaxed and cajoled than as comrades fighting for a common cause.

(2) George Goschen, speech in the House of Commons (3rd March, 1884)

The argument against the enfranchisement of the working class was this - and no doubt it is a very strong argument - the power they would have in any election if they combined together on questions of class interest. We are bound not to put that risk out of sight. Well, at the last election, I carefully watched the various contests that were taking place and I am bound to admit that I saw no tendency on the part of the working classes to combine on any special question where their pecuniary interests were concerned. On the contrary, they seemed to me to take a genuine political interest in public questions ... The working classes have given proofs that they are deeply desirous to do what is right.

(3) The Spectator (12th April, 1884)

Mr. Gladstone contended that every Reform Bill had improved the House as a Representative Assembly, on which cries of "No, no !" were heard from the Conservative benches, and received with laughter by the House, whereupon Mr. Gladstone insisted that whatever might be the effect on the House from some points of view, it was past doubt that the two Reform Acts had made the House far more adequate to express the wants and wishes of the nation as a whole. He denied that in 1866 there was any more excitement amongst the unenfranchised classes than there now is; but the Bill of 1866 was no sooner defeated, than the Conservatives found it absolutely necessary to deal with the question, and so it would be again.

(4) William Gladstone, memorandum on the House of Lords sent to Queen Victoria (August, 1884)

The House of Lords has for a long period been the habitual and vigilant enemy of every Liberal Government... It cannot be supposed that to any Liberal this is a satisfactory subject of contemplation. Nevertheless some Liberals, of whom I am one, would rather choose to bear all this for the future as it has been borne in the past, than raise the question of an organic reform of the House of Lords. The interest of the party seems to be in favour of such an alteration: but it should, in my judgement, give way to a higher interest, which is national and imperial: the interest of preserving the hereditary power as it is, if only it will be content to act in such a manner as will render the preservation endurable.

I do not speak of this question as one in which I can have a personal interest or share. Age, and political aversion, alike forbid it. Nevertheless, if the Lords continue to reject the Franchise Bill, it will come.

I wish (an hereditary House of Lords) to continue, for the avoidance of greater evils. These evils are not only long and acrimonious controversy, difficulty in devising any satisfactory mode of reform, and delay in the general business of the country, but other and more permanent mischiefs. I desire the hereditary principle, notwithstanding its defects, to be maintained, for I think it in certain respects an element of good, a barrier against mischief. But it is not strong enough for direct conflict with the representative power, and will only come out of the conflict sorely bruised and maimed. Further; organic change of this kind in the House of Lords may strip and lay bare, and in laying bare may weaken, the foundations even of the Throne.

the obstructiveness of the Lords for the past fifty years the subject of his speech. He was himself, be said, convinced that compromise was the life of politics ; but the Franchise Bill was a compromise, and if the Lords threw it out again, that would mean that the minority were to govern, and that a Liberal Government must pass a Tory Reform Bill. The demand for Redistribution was a demand that Tory Lords should dictate to the Commons the method of Reform. He held that the offer to pass the Franchise Bill if a Redistribution Bill were introduced would,.if accepted, be "a betrayal and a humiliation," and that the proposal to send up the Bill again and again was useless under the Septennial Act. He has, therefore, occasionally thought that Mr. Gladstone, if thus driven, might propose a complete Re- form Bill,—one including the Franchise, Redistribution, and "the clipping of the pinions of the House of Lords." The English people were a patient and a Conservative people, but they would not endure a stoppage of legislation by a House which had long been as injurious in practice as indefensible in theory. If the struggle once began, it was inevitable that the days of privilege should be numbered.

(5) The Spectator (13th September, 1884)

He (John Morley) was himself, be said, convinced that compromise was the life of politics; but the Franchise Bill was a compromise, and if the Lords threw it out again, that would mean that the minority were to govern, and that a Liberal Government must pass a Tory Reform Bill. The demand for Redistribution was a demand that Tory Lords should dictate to the Commons the method of Reform. He held that the offer to pass the Franchise Bill if a Redistribution Bill were introduced would,.if accepted, be "a betrayal and a humiliation," and that the proposal to send up the Bill again and again was useless under the Septennial Act. He has, therefore, occasionally thought that Mr. Gladstone, if thus driven, might propose a complete Reform Bill, one including the Franchise, Redistribution, and "the clipping of the pinions of the House of Lords." The English people were a patient and a Conservative people, but they would not endure a stoppage of legislation by a House which had long been as injurious in practice as indefensible in theory. If the struggle once began, it was inevitable that the days of privilege should be numbered.

(6) Paul Foot, The Vote (2005)

On 21 July, an estimated 30,000 people marched through the city to merge with at least that many already assembled in the park... "Down with the Lords - Give us the Bill" was the universal slogan. The Radical MP for Southwark, Professor Thorold Rogers, likened the House of Lords to "Sodom and Gomorrah and the abominations of the Egyptian temple". Joseph Chamberlain told the biggest of the seven crowds: "We will never, never, never be the only race in the civilized world subservient to the insolent pretensions of a hereditary caste." His speech produced a furious response from Her Majesty the Queen. Queen Victoria was opposed to the extension of the franchise - no one, after all, had elected her - but she was much more concerned that the rising temperature of popular fury would sweep away her beloved House of Lords. In August, Chamberlain held a series of enormous meetings in Birmingham at which he denounced the Lords with renewed fervour. The Queen protested again - and again: on 6, 8 and 10 August. In the pathetic belief that as many of her people supported the Lords as opposed them, she encouraged the Tory leaders to whip up counter-demonstrations in favour of the Lords and against the extension of the suffrage. Lord Randolph Churchill obliged at once and urged Midlands Tories to organize a huge ticket-only Queen, Country and Lords meeting at Aston Park for 13 October. Birmingham Radicals organized a mass purchase of tickets. When the meeting opened, it was immediately clear that the Tories were in a minority. A near-riot ensued. Seats were ripped up and hurled at the platform. "At last - a proper distribution of seats!" was the triumphant shout of the demonstrators.

When Parliament reconvened, on 6 November, Gladstone brought a new, very similar franchise Bill to the Commons once again, and the Tories moved the same amendment. The speeches bore witness to the mood of the country. Thorold Rogers persisted in his contemptuous assault on the House of Lords. For this blatant defiance of the rules of the House, Rogers was not even reprimanded.

(7) Samuel Smith, speech in the House of Commons (6th November, 1884)

In the country, the agitation has reached a point which might be described as alarming. I have no desire to see the agitation assume a revolutionary character which it would certainly assume if it continued much longer.... I am afraid that there would emerge from out of the strife a new party like the social democrats of Germany and that the guidance of parties would pass from the hands of wise statesmen into that of extreme and violent men.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)