Marianne Gärtner

Marianne Gärtner was born in Berlin, Germany, in 1926. Both her parents were supporters of Adolf Hitler. Her father, a successful businessman, told her that Hitler was "someone who has come to liberate his people and his country". He joined the Nazi Party and Marianne remembers his "brand-new uniform was hanging in his wardrobe in between a fine worsted suit and a dinner jacket".

At school she liked the new system of education. "There had been a lot of changes in school (after 1933).... None of my neatly dressed, well-behaved primary-school mates questioned the new books, the new songs, the new syllabus, the new rules or the new standard script, and when - in line with national socialist educational policies - the number of PT periods was increased at the expense of religious instruction or other classes, and competitive field-events added to the curriculum, the less studious and the fast-legged among us were positively delighted." (1)

Marianne took part in the Youth Pageant that opened the 1936 Olympic Games. "My father had organised tickets for the main athletic events and I was privileged to watch Jesse Owens set new world records, a Japanese come first in the marathon and Finnish runners triumph over the long distances... As I watched the athletes, and shared the champions' euphoria and the losers' disappointment, I bit my nails, cheered, applauded or sighed in chorus with the crowd." (2)

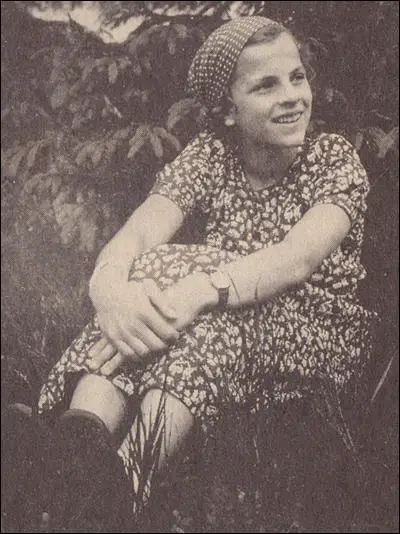

Marianne Gärtner in Potsdam

After her parent's divorce, Marianne was sent to Potsdam to "board in a girls' home catering for orphans and daughters from broken marriages" and attended a local fee-paying girls' secondary school. "I tried not to think too much of my parents, preoccupied as they were with the demands of their own lives - my father, the busy sales director of one of the country's leading steel companies, my mother now earning her living as a secretary at Luftwaffe headquarters." (3)

Marianne Gärtner was taught that she was a member of the Master Race: "A special period dealt with the role the Jews had played in the German economy, and the threat they represented to the master race. To back up the lecture, a film was shown which portrayed the archetypal Jew as a suave, potbellied and shifty-eyed city type posing beside gargantuan moneybags. Alternatively, he was depicted as a long-bearded, sunken eyed scarecrow of a man who inspired fear and revulsion. The soundtrack spat the film-makers' contempt into the classroom: The Jews are eyesores on the German landscape, boils on the back of the German people, a subhuman species comparable only to rats! A voice seething with chilling hatred: They must be eradicated!" (3a)

Marianne Gärtner was a talented athlete: "In my second year at school it became evident that I was good at sports. I was not only leaving my mark in the gym hall but on the sports field, where I ran faster, jumped farther or higher, and managed to put more power behind the ball than anyone else. It was an exhilarating experience to be good at something, and to feel superior to the rest of the class for at least an hour a day, for socially, in my drab, institutional dress, I found myself miles apart from the daughters of titled parents, high-ranking officers and government officials." (4)

German Girls' League

During this period she joined the German Girls' League. This involved taking the oath: "I promise always to do my duty in the Hitler Youth, in love and loyalty to the Führer." Other mottos she was taught included: "Führer, let's have your orders, we are following you!", "Remember that you are a German!" and "One Reich, one people, one Führer!". As she later admitted: "I was, however, not thinking of the Führer, nor of serving the German people, when I raised my right hand, but of the attractive prospect of participating in games, sports, hiking, singing, camping and other exciting activities away from school and the home.... I acquired membership, and forthwith attended meetings, joined ball games and competitions, and took part in weekend hikes; and I thought that whether we were sitting in a circle around a camp fire or just rambling through the countryside and singing old German folk songs." (5)

Marianne Gärtner was introduced to the ideas of Adolf Hitler at these meetings. Hitler disliked women who smoked and wore make-up. He made it clear about how young women in Nazi Germany should behave. The American journalist, Wallace R. Deuel, pointed out that he read in the Völkischer Beobachter, a newspaper controlled by the Nazi Party, that: "The most unnatural thing we can encounter in the streets is a German woman, who, disregarding all laws of beauty, has painted her face with Oriental warpaint." (6) Marianne Gärtner was told at one meeting: "A German woman does not use make-up! Only Negroes and savages paint themselves! A German woman does not smoke! She has a duty to her people to keep fit and healthy! (7)

The German Girls' League (BDM) played an important role in developing these values: "They were trained in Spartan severity, taught to do without cosmetics, to dress in the simplest manner, to display no individual vanity, to sleep on hard beds, and to forgo all culinary delicacies; the ideal image of those broad-hipped figures, unencumbered by corsets, was one of radiant blondeness, crowned by hair arranged in a bun or braided into a coronet of plaits. As a negative counter-image Nazi propaganda projected the combative, man-hating suffragettes of other countries." (8)

At another meeting, while addressing the girls on the desirability of large, healthy families, the team leader raised her voice: "There is no greater honour for a German woman than to bear children for the Führer and for the Fatherland! The Führer has ruled that no family will be complete without at least four children, and that every year, on his mother's birthday, all mothers with more than four children will be awarded the Mutterkreuz." (Decoration similar in design to the Iron Cross (came in bronze, silver or gold, depending on number of children).

The team leader then asked for questions: "Why isn't the Führer married and a father himself?" Marianne Gärtner explained in her autobiography, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987): "The question was out before I had time to check myself. It was an innocent question, devoid of any pert insinuation that the Führer ought to practise what he preached. Silence filled the whitewashed room, but the team leader offered neither answer nor reproved the question. She strafed me with a murderous look, then called for attention." The question was never answered. (9)

European Athletic Youth Championships

During the Second World War the Nazi government continued to use athletics as a propaganda weapon. In 1942 it organized the European Athletic Youth Championships in Milan. The only countries that took part were its allies and those European countries under occupation. Marianne Gärtner was chosen to represent Germany. In the trials she ran the 100 metres in 12.5 seconds, one tenth of a second over the national women's record.

Marianne was a member of the German 4 x 100 metre relay team: "An expectant silence settles over the terraces. The gun goes off, the first runners shoot out of their starting blocks. Brunhilde takes the bend, and I begin to calculate the moment when to start running, in order to effect a swift baton-change - not too fast, lest I overshoot the line, not too slow, lest I lose valuable tenths of seconds. The sky, however, does not give a damn about the dramatic minute ticking away on the ground and opens up a torrential downpour. Seconds later, I feel a wet baton placed in my outstretched hand, and I thrust myself against the wall of blinding, pelting rain which is washing my face, seeping into my mouth, tasting of nothing. The stadium explodes. Cheers are showering the Italian runner in the neighbouring lane, ecstasy is pulling the crowd from their seats, is threatening me. And now I am not running for myself, but for Germany, my fatherland, the country of pine forests, Silesian mountains and Rubezahl legends, of Schubert impromptus, noble Beethoven symphonies and romantic evening songs; the country of Goethe and childhood stories, of apple pancakes and Nusstortchen, horse chestnuts and giant sunflowers... Then it is all over. I smoothly hand over my baton to Inga and, as through a net curtain, watch her going into the bend and Maria sprinting home for victory on the final stretch."

Their time of 48.8 seconds was a new European record. After the race, an exultant team leader told them. "Well done, girls! Well done! Now, listen: on points, the German girls' team has come first in the championships, far ahead of the Italians and the Dutch. Congratulations to you all!" They ask about the boys: "Second, the team leader replied, looking suddenly piqued, not wasting another syllable on such humiliating news, but packing into her final statement all her pride and gratification: At least you, girls, have not let the Reich down!" (10)

Stalingrad

Marianne Gärtner, like most young people, took a keen interest in the progress of the war. After her return to Germany the main topic of conversation was the Eastern Front. In the summer of 1942 General Friedrich Paulus advanced toward Stalingrad with 250,000 men, 500 tanks, 7,000 guns and mortars, and 25,000 horses. At the end of July 1942, a lack of fuel brought Paulus to a halt at Kalach. It was not until 7th August that he had received the supplies needed to continue with his advance. Over the next few weeks his troops killed or captured 50,000 Soviet troops but on 18th August, Paulus, now only thirty-five miles from Stalingrad, ran out of fuel again. (11)

Joseph Stalin insisted that the city should be held at all costs. One historian has claimed that he saw Stalingrad "as the symbol of his own authority." Stalin also knew that if Stalingrad was taken, the way would be open for Moscow to be attacked from the east. If Moscow was cut off in this way, the defeat of the Soviet Union was virtually inevitable. A million Soviet soldiers were drafted into the Stalingrad area. They were supported from an increasing flow of tanks, aircraft and rocket batteries from the factories built east of the Urals, during the Five Year Plans. Stalin's claim that rapid industrialization would save the Soviet Union from defeat by western invaders was beginning to come true.

The heavy rains of October turned the roads into seas of mud and the 6th Army's supply conveys began to get bogged down. On 19th October the rain turned to snow. Paulus continued to make progress and by the beginning of November he controlled 90 per cent of the city. However, his men were now running short of ammunition and food. Despite these problems Paulus decided to order another major offensive on 10th November. The German Army took heavy casualties for the next two days and then the Red Army launched a counterattack. Paulus was forced to retreat southward but when he reached Gumrak Airfield, Adolf Hitler ordered him to stop and stand fast despite the danger of encirclement. Hitler told him that Hermann Goering had promised that the Luftwaffe would provide the necessary supplies by air.

Now aware that the 6th Army was in danger of being starved into surrender, Adolf Hitler ordered Field Marshal Erich von Manstein and the 4th Panzer Army to launch a rescue attempt. Manstein managed to get within thirty miles of Stalingrad but was then brought to a halt by the Red Army. On 27th December, 1942, Manstein decided to withdraw as he was also in danger of being encircled by Soviet troops. (12)

In Stalingrad over 28,000 German soldiers had died in just over a month. With little food left General Friedrich Paulus gave the order that the 12,000 wounded men could no longer be fed. Only those who could fight would be given their rations. Erich von Manstein now gave the order for Paulus to make a mass breakout. Paulus rejected the order arguing that his men were too weak to make such a move. On 30th January, 1943, Hitler promoted to Paulus to field marshal and sent him a message reminding him that no German field marshal had ever been captured. Hitler was clearly suggesting to Paulus to commit suicide but he declined and the following day surrendered to the Red Army. (13)

Marianne Gärtner and the other students were told the news at a special school assembly. "A voice that seems offensive in its forced neutrality, announces that the Sixth Army, under the exemplary leadership of Field Marshall von Paulus, has succumbed to superior forces and to adverse conditions... The national lament fills the hall. The school stands up and joins the chorus, then the headmaster takes over. His shaking voice pays respect to the emotiveness of the hour. Sit down, school! This is of course a disaster beyond all comprehension. The Russian winter... the superiority of the enemy ... our losses. He clears his throat, fingers his tie, reassumes formal bearing. And what can we do? Well, in the months to come, we must try harder than ever to prove ourselves worthy of the men who gave their lives out there, worthy too of the wounded, and of the men now entering Russian prison camps.

She later reported that many of the girls were in tears: "I am no longer listening, and I feel as if all the mothers, wives and sweethearts of the men in Stalingrad have chosen me as the receptacle for their grief. Images come running: legions of snow-covered corpses, endless columns of exhausted, half-frozen prisoners stumbling east into a cold whiteness that has no horizon. And the wounded... I feel sick, I feel like standing up and screaming, from the centre of the hall where I am sitting... Instead I probe my pocket for a handkerchief. The girl on my right is noisily unwrapping some paper, the one on my left is playing with the buttons on her dress. The headmaster's voice rattles on: Three days of national mourning have been declared, during which the school will remain closed. Now, leave the hall quietly, and go home. Remember, girls, this is a very sad day, a national tragedy. School dismissed. Heil Hitler!" (14)

Marianne Gärtner admitted that the news changed the mood of Potsdam: "Over the coming weeks, the street scene changed visibly. Bars, dance halls, many shops and restaurants closed; older men were called up, women without young children and within a certain age group were drafted into factories, sent to farms or trained in defence units. Except for the presence of old people and children, and of soldiers walking on crutches or with limp sleeves pinned to their uniform jackets, Potsdam's streets now looked deserted during the day. Rations were cut once again, the collection of money and expendable clothes stepped up." (15)

In her autobiography, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987), Marianne believed that after Stalingrad schools in Nazi Germany changed its focus: "For years, Party and Hitler Youth propaganda had been levelled against Jews, Bolshevists, German communists and the country's western enemies. Now, with the war in its fourth year, it seemed that the time had come for schools to play a more effective role in the campaign against the enemy without and within, for the tenor of the messages suddenly drummed into the classroom made it quite clear that someone high up, if not Goebbels himself, had poked his finger into the curriculum.... Subjects were chosen to provoke the mind, to breed contempt or mockery: the Boer War. The Englander as the originators of concentration camps. The ruthless master role played by British colonial traders and administrators. Henry VIII, the syphilitic Bluebeard. Victorian child labour. Drudgery in mills and mines. Life in the slums of foggy London. The exploitation of the English working class by bowler-hatted, fox-hunting men." (16)

Extermination Camps

In 1944 Marianne's father was expelled from the Nazi Party. He told his daughter that he had been "summoned before a special tribunal and been charged with conduct unbecoming to a member of the Party, such as failing to greet other members in the street with a raised arm or to wear his badge in public, not to mention his absenteeism from Party meetings over the years." He was also accused of making jokes about the German government. He was punished by being posted to a place near Warsaw to run a steel mill. "It's manned entirely by Polish and Russian forced labour, supervised by German foremen and guarded by the SS. I'm afraid it smacks of a suicide mission, for the Polish underground is getting stronger with every kilometre the Russians are gaining.

While in Poland he discovered details of the extermination camps. He told his daughter about what he had heard: "I suppose I shouldn't tell you, it's too horrendous, too risky if passed on carelessly. But then, you're old enough. Promise me you won't talk to anyone about it? It's the Jews, `I have it from a reliable source that they are carted off to special camps to be killed by gas, whole waggon loads of men, women and children.... As God is my witness, when I joined the Party in 1936, never in my wildest dreams did I think that it would come to this!" (17)

Labour Service

Desperately short of workers, the government used the German Girls' League and the Hitler Youth as cheap labour. (16) In the summer of 1944, Marianne Gärtner was sent to Warta, east of the River Oder as part of her Labour Service. "I quickly adapted to camp life - to soft soap, field-kitchen hotspots and the smell of cabbage, sweat and latrines, to duty rosters, organised leisure, singsongs and politically-orientated lectures. In the process I fell meekly into step and trod softly where objectors or grumblers, dreamers or loners were not, and could not, be tolerated. I peeled potatoes and chopped cabbage; I washed shirts, ladled soup, sliced mountains of Kommissbrot (very dark, rough, army-style bread), distributed bars of chocolate; I was taught how to read a map, how to operate a field telephone and how to sneak up on an enemy by making the best of natural cover. And it always came back to sitting in a circle, back to vats and pails, to peeling and chopping, singing and squashing mosquitoes." (18)

On 20th July, 1944, Marianne Gärtner heard about the attempt on the life of Adolf Hitler by Claus von Stauffenberg and his group (July Plot). The camp leader told the young people: "This is a moment none of us will ever forget, for the day will go down in the history as one which the infamy of a few made a whole nation hold its breath! There has been an attempt to assassinate the Führer, but we are happy to tell you that this attempt has failed and the Führer has sustained no injuries." Marianne was deeply shocked by the news: "Why should anyone want to kill Hitler, I wondered. To end the war? To remove him as head of the nation? Did some people really hate him that much?" (19)

End of the War

In February 1945, Marianne Gärtner and other members of the BDM were forced to flee from the advancing Red Army. She arrived back in Berlin to discover a city under heavy attack. With the help of her father she managed to get to the Tangermünde. She began working in a local factory. Most of her fellow workers were foreigners. She was told: "Many have been with us for years... Dutch, Belgians, French, we even have some Poles and Czechs. As you can imagine, they're getting pretty restless."

In April they received news that American troops had formed a bridgehead upriver near the city of Magdeburg. A few days later her friend Gisela told her: "I've heard at the office that a company of Negro soldiers is moving towards the town and could be here by nightfall. I have no idea where the rumour is coming from, but it's all over town, and the men say the women shouldn't take any chances, because the first thing the blacks will do is to rape them... sort of blacken pure Aryan blood." (20)

Since the German Army began to retreat in 1943, Marianne Gärtner had heard plenty of stories of German women being treated very badly by the invading armies. One newspaper had argued that "the sexual abuse of the German woman is the final drama of the war". As she later explained: "The fear of rape hits my empty stomach like a boxer's fist; it is pressing my thighs together. What would rape be like? Would it make me die slowly inside, and afterwards torment me for ever with a sense of defilement, a disgust for my body? Was there not ample evidence for such humiliations in recent history?... I can still hear refugees in shop queues and in the market square narrating the harrowing experiences of women brutally raped by Russian soldiers during their advance on Berlin and in the course of their protracted victory celebrations." (21)

Marianne Gärtner was actually treated very well by the Americans and she was recruited for the post of interpreter. "In my capacity as interpreter I was also getting out and about a lot, being whirled by jeep to factories, estates and outlying farmsteads, to warehouses, harbour installations, the prison or the hospital. I had become a familiar sight in town at the side of the major and his aide - exposed not only to the contemptuous stares of many Tangermunders who might have thought of themselves as 'decent' Germans, but to slanderous talk, not always behind my back. That's her... she works for the Americans... they say she sleeps with the Kommandant! Of course, she's not a local girl!" And they would know 'for certain' that for prostituting my services to the major, interpreting, secretarial or otherwise, I was being amply rewarded with butter and eggs and chocolate and nylons, and those lovely American tins of beef. Surely, so their faces implied as I ran their gauntlet, I was no less than a collaborator, someone not worthy of their spit!" (22)

In 1948 Marianne Gärtner moved to England and became a qualified translator. In 1957 she married a Ministry of Defence Intelligence Officer and over the next few years gave birth to three sons. The couple divorced in 1978. (23) She moved to Glasgow and in 1987 Marianne MacKinnon published an autobiography, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987). Other books by her include The Alien Years (1991) and A Slow Boat to Hong Kong (2009).

Primary Sources

(1) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987)

There had been a lot of changes in school, too (after 1933). Some had been barely noticed, others had been introduced as though with drums and trumpets. None of my neatly dressed, well-behaved primary-school mates questioned the new books, the new songs, the new syllabus, the new rules or the new standard script, and when - in line with national socialist educational policies - the number of PT periods was increased at the expense of religious instruction or other classes, and competitive field-events added to the curriculum, the less studious and the fast-legged among us were positively delighted.The rector spelled it out for us. "Physical fitness is everything! It is what the Führer wants for you. It is what you want in order to grow strong and healthy!"

In class, Frau Bienert, our form teacher, explained why a healthy mind could only be found in a healthy body, and - instead of two PT periods a week - the revised time-table featured a daily class and a compulsory weekly games afternoon. Running, jumping, throwing balls, climbing ropes, swinging on the bars or doing rhythmic exercises to music, we fitted smoothly into the new pattern of things, into a scheme which, for most of us, appeared to be an attractive feature of national socialism, for an hour spent in the gym or on the sports pitch seemed infinitely preferable to sweating over arithmetic or German grammar.

I loved the new physical-fitness programme, but not the loud, aggressive songs we had to learn, the texts of which our music teacher would rattle off in a funereal voice. But then, Fraulein Kanitzki had been born in the Cameroons and suffered from bouts of malaria, which, in our eyes, entitled her to some form of eccentricity. And it was no secret that she never raised her arm in the "Heil Hitler!" salute at the beginning of class or in the school corridors; she was always conveniently hugging sheets of music or books under her right arm, which prevented her from performing the prescribed motion. The new greeting was, after all, a bore. Arm up, arm down. Up, down. But it was the formal salute in Germany now, and everyone did as they were told, including my father.

(3) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987)

One day, fittingly enough on Hitler's birthday, my age group was called up and I took the oath: "I promise always to do my duty in the Hitler Youth, in love and loyalty to the Führer." Service in the Hitler Youth, we were told, was an honourable service to the German people. I was, however, not thinking of the Führer, nor of serving the German people, when I raised my right hand, but of the attractive prospect of participating in games, sports, hiking, singing, camping and other exciting activities away from school and the home. A uniform, a badge, an oath, a salute. There seemed to be nothing to it. Not really. Thus, unquestioningly, and as smoothly as one day slips into another, I acquired membership, and forthwith attended meetings, joined ball games and competitions, and took part in weekend hikes; and I thought that whether we were sitting in a circle around a camp fire or just rambling through the countryside and singing old German folk songs...

There were now lectures on national socialism, stories about modern heroes and about Hitler, the political fighter, while extracts from Mein Kampf were used to expound the new racial doctrines. And there was nothing equivocal about the mother-role the Führer expected German women to play.

At one meeting, while addressing us on the desirability of large, healthy families, the team leader raised her voice:

"There is no greater honour for a German woman than to bear children for the Führer and for the Fatherland! The Führer has ruled that no family will be complete without at least four children, and that every year, on his mother's birthday, all mothers with more than four children will be awarded the Mutterkreuz. (Decoration similar in design to the Iron Cross (came in bronze, silver or gold, depending on number of children).

Make-up and smoking emerged as cardinal sins.

"A German woman does not use make-up! Only Negroes and savages paint themselves! A German woman does not smoke! She has a duty to her people to keep fit and healthy! Any questions?"

"Why isn't the Führer married and a father himself?" The question was out before I had time to check myself. It was an innocent question, devoid of any pert insinuation that the Führer ought to practise what he preached. Silence filled the whitewashed room, but the team leader offered neither answer nor reproved the question. She strafed me with a murderous look, then called for attention.

"Now, I want you all to learn the Horst Wessel Lied by next Wednesday. All three verses. And don't forget the rally on Saturday! Make sure your blouses are clean, your shoes polished, your cheeks rosy and your voices bright! Hell Hitler! Dismissed!"

Perhaps not surprisingly, by the time I celebrated my thirteenth birthday, my initial Wanderlied and camping euphoria had gone flat and I felt bored with a movement which not only did not tolerate individualists but expected its members to venerate a flag as if it were God Almighty, and which made me march or stand en bloc for hours, listen to tiresome or inflammatory speeches, sing songs not composed for happy hours or shout Führer, let's have your orders, we are following you!, one of the many slogans which, somehow, went into one ear and out the other.

But being old enough to realise that absenteeism from group and mass meetings, or a negative response to the demands of the movement, would be treated as political maladjustment, I thought it wise not to step out of line. Remember that you are a German! they said, and that there was only One Reich, one people, one Führer!, a motto which, like others, if trumpeted loud and long enough, would often come dangerously close to a Bible truth.

(3) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987)

The opening ceremony of the Games, with its flag raising, fanfares and massed display reminded me of the Berlin Olympics six years before. Much water had since flowed down the river Havel, as Berliners liked to allegorise the passing of time - years in which I had made it from a terrace seat down to the stadium track. Now, instead of the Führer, Count Ciano, Italy's minister for foreign affairs, took the salute in the march past of the participants and, after a rousing speech, declared the Games open....

The stadium over which earlier rain-showers had formed a dome of humid heat, was packed with thousands of spectators in a rally mood which reached fever pitch the moment the girls' 4 x 100 metre relay finals were announced... An expectant silence settles over the terraces. The gun goes off, the first runners shoot out of their starting blocks. Brunhilde takes the bend, and I begin to calculate the moment when to start running, in order to effect a swift baton-change - not too fast, lest I overshoot the line, not too slow, lest I lose valuable tenths of seconds. The sky, however, does not give a damn about the dramatic minute ticking away on the ground and opens up a torrential downpour. Seconds later, I feel a wet baton placed in my outstretched hand, and I thrust myself against the wall of blinding, pelting rain which is washing my face, seeping into my mouth, tasting of nothing. The stadium explodes. Cheers are showering the Italian runner in the neighbouring lane, ecstasy is pulling the crowd from their seats, is threatening me. And now I am not running for myself, but for Germany, my fatherland, the country of pine forests, Silesian mountains and Rubezahl legends, of Schubert impromptus, noble Beethoven symphonies and romantic evening songs; the country of Goethe and childhood stories, of apple pancakes and Nusstortchen, horse chestnuts and giant sunflowers...

Then it is all over. I smoothly hand over my baton to Inga and, as through a net curtain, watch her going into the bend and Maria sprinting home for victory on the final stretch. In true mocking style, this is also the moment it decides to stop raining, and it does so as abruptly as if someone has turned off a shower tap. A shout behind me: "We've won!"

The loudspeaker blares out the result in Italian and German, proclaiming "Alemagna" to be the winner and the German team's time of 48.8 seconds to be a new European record. The announcement is greeted with measured applause from the grandstand, to be joined seconds later by a roar from the terraces, when "Italia" is named as the runner-up. I take off my running shoes. This is it then! We have won! We have done our bit, I have done mine.

But first our relay team has to step on to the top tier of the rostrum for the prize-giving ceremony. I stand in front and in full view of the grandstand from where Count Ciano - uniformed, bemedalled and oozing southern charm - descends to make the presentation. A moist, flabby handshake, a screen smile, a medal and a silver cup for each member of the squad. The German national anthem resounds in perfect brass harmony. The sun is breaking through the clouds, turning the cups into flashing beacons. With our heads held high, our right arms outstretched, we watch the hoisting of the flag...

In the changing room, an exultant team leader pats backs and shakes hands. "Well done, girls! Well done! Now, listen: on points, the German girls' team has come first in the championships, far ahead of the Italians and the Dutch. Congratulations to you all!"

"... and the boys?"

"Second," the team leader replied, looking suddenly piqued, not wasting another syllable on such humiliating news, but packing into her final statement all her pride and gratification: "At least you, girls, have not let the Reich down!"

(4) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987)

In school, there is a special assembly this morning... A voice that seems offensive in its forced neutrality, announces that the Sixth Army, under the exemplary leadership of Field Marshall von Paulus, has succumbed to superior forces and to adverse conditions...

The national lament fills the hall. The school stands up and joins the chorus, then the headmaster takes over. His shaking voice pays respect to the emotiveness of the hour.

"Sit down, school! This is of course a disaster beyond all comprehension. The Russian winter .., the superiority of the enemy ... our losses." He clears his throat, fingers his tie, reassumes formal bearing. "And what can we do? Well, in the months to come, we must try harder than ever to prove ourselves worthy of the men who gave their lives out there, worthy too of the wounded, and of the men now entering Russian prison camps."

I am no longer listening, and I feel as if all the mothers, wives and sweethearts of the men in Stalingrad have chosen me as the receptacle for their grief. Images come running: legions of snow-covered corpses, endless columns of exhausted, half-frozen prisoners stumbling east into a cold whiteness that has no horizon. And the wounded...

I feel sick, I feel like standing up and screaming, from the centre of the hall where I am sitting, "Why? Will someone please tell me why?"

Instead I probe my pocket for a handkerchief. The girl on my right is noisily unwrapping some paper, the one on my left is playing with the buttons on her dress. The headmaster's voice rattles on: "Three days of national mourning have been declared, during which the school will remain closed. Now, leave the hall quietly, and go home. Remember, girls, this is a very sad day, a national tragedy. School dismissed. Heil Hitler!"

(5) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987)

For years, Party and Hitler Youth propaganda had been levelled against Jews, Bolshevists, German communists and the country's western enemies. Now, with the war in its fourth year, it seemed that the time had come for schools to play a more effective role in the campaign against the enemy without and within, for the tenor of the messages suddenly drummed into the classroom made it quite clear that someone high up, if not Goebbels himself, had poked his finger into the curriculum...

Subjects were chosen to provoke the mind, to breed contempt or mockery: the Boer War. The Englander as the originators of concentration camps. The ruthless master role played by British colonial traders and administrators. Henry VIII, the syphilitic Bluebeard. Victorian child labour. Drudgery in mills and mines. Life in the slums of foggy London. The exploitation of the English working class by bowler-hatted, fox-hunting men. American slave-trading and slave-keeping practices. U.S. capitalism. The list was long - and we pricked our ears, stifled yawns or shuddered with appropriate horror.

A special period dealt with the role the Jews had played in the German economy, and the threat they represented to the master race. To back up the lecture, a film was shown which portrayed the archetypal Jew as a suave, potbellied and shifty-eyed city type posing beside gargantuan moneybags. Alternatively, he was depicted as a long-bearded, sunken eyed scarecrow of a man who inspired fear and revulsion. The soundtrack spat the film-makers' contempt into the classroom: "The Jews are eyesores on the German landscape, boils on the back of the German people, a subhuman species comparable only to rats!" A voice seething with chilling hatred: "They must be eradicated!"

(6) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987)

I quickly adapted to camp life - to soft soap, field-kitchen hotspots and the smell of cabbage, sweat and latrines, to duty rosters, organised leisure, singsongs and politically-orientated lectures. In the process I fell meekly into step and trod softly where objectors or grumblers, dreamers or loners were not, and could not, be tolerated. I peeled potatoes and chopped cabbage; I washed shirts, ladled soup, sliced mountains of Kommissbrot (very dark, rough, army-style bread), distributed bars of chocolate; I was taught how to read a map, how to operate a field telephone and how to sneak up on an enemy by making the best of natural cover. And it always came back to sitting in a circle, back to vats and pails, to peeling and chopping, singing and squashing mosquitoes.

In the evenings, we joined the boys around the camp fire while the camp leader told stories about Hitler Youth heroes... And then it was time for songs in which banners were "flying towards a new dawn" and "courageously leading the way to victory", or in which the new era was "marching ahead" - songs which did not make much sense and which, in celebrating the great cause, seemed somehow no longer to form the same bond of comradeship and unity as in earlier years. But invariably, as the evening wore on, we struck up Heimatlieder - simple folk songs passed on from generation to generation, which created a more traditional sense of belonging, and made even the boys' voices sound more mellow.

(7) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987)

The fear of rape hits my empty stomach like a boxer's fist; it is pressing my thighs together. What would rape be like? Would it make me die slowly inside, and afterwards torment me for ever with a sense of defilement, a disgust for my body? Was there not ample evidence for such humiliations in recent history?... I can still hear refugees in shop queues and in the market square narrating the harrowing experiences of women brutally raped by Russian soldiers during their advance on Berlin and in the course of their protracted victory celebrations.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 36

(2) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 40

(3) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 46

(4) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 124

(5) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 51

(6) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 53

(7) Wallace R. Deuel, People Under Hitler (1942) page 161

(8) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 54

(9) Richard Grunberger, A Social History of the Third Reich (1971) page 335

(10) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 55

(11) Louis L. Snyder, Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (1998) page 267

(12) William L. Shirer, the author of The Rise and Fall of Nazi Germany (1959) page 1106

(13) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 690

(14) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) pages 123-124

(15) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 115

(16) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 116

(17) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 123

(18) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 149

(19) James Taylor and Warren Shaw, Dictionary of the Third Reich (1987) page 168

(20) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 161

(21) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 6

(22) Marianne Gärtner, The Naked Years: Growing up in Nazi Germany (1987) page 238

(23) Alastair Warren, Glasgow Herald (27th June, 1987)