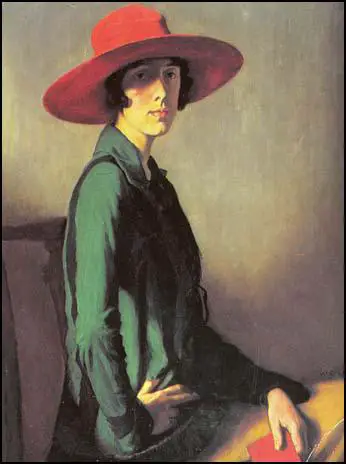

Vita Sackville-West

Vita Sackville-West, the only daughter of Lionel Edward Sackville-West (1867–1928), and his wife and first cousin, Victoria Josefa Dolores Catalina Sackville-West (1862–1936), was born in Knole House, near Sevenoaks on 9th March 1892.

Vita was educated at home by a governess until she was thirteen when she went to Helen Wolff's school for girls, in Park Lane. Other pupils at the school were Violet Keppel and Rosamund Grosvenor. Vita began to write at an early age and completed eight historical novels, five plays, and a number of poems before she was eighteen.

While at school she began an affair with Rosamund, who was four years her senior. Vita recorded in her diary after Rosamund went on holiday: "After Roddie (Rosamund) had gone I cried because I missed her. What a funny thing it is to love a person as I love Roddie". Vita also became very close to Violet Keppel, the daughter of Alice Keppel and the mistress of King Edward VII. Violet described Vita as "tall for her age, gawky, dressed in what appeared to be her mother's old clothes." Violet spent a great deal of time at Vita's house. In May 1908 Vita, Rosamund and Violet went on holiday to Pisa, Milan, and Florence together.

Her father, Lionel Edward Sackville-West, succeeded her grandfather, Lionel Sackville-West (1827-1908), as third Baron Sackville in September 1908. Vita's biographer, T. J. Hochstrasser, has argued: "Her upbringing, both privileged and solitary, was shaped above all by the romantic atmosphere and associations of Knole, the sprawling Tudor palace set in a spacious park in Kent, where she spent her childhood. Her literary taste and temperament were created substantially by this aristocratic and historical backcloth and intensified both by the colourful and eccentric personality of her mother and by the gradual realization, with which she never entirely came to terms, that as a woman she could never inherit the Knole estate."

Vita lost contact with Violet Keppel but when they were reunited a few years later, the relationship became even more intense. Violet wrote in her autobiography, Don't Look Round: "No one had told me that Vita had turned into a beauty. The knobs and knuckles had all disappeared. She was tall and graceful. The profound, hereditary Sackville eyes were as pools from which the morning mists had lifted. A peach might have envied her complexion. Round her revolved several enamored young men."

In 1910 Victoria Sackville-West invited Rosamund Grosvenor to stay with them in Monte Carlo. Vita later recalled that "Rosamund was... invited by mother, not by me; I would never have dreamt of asking anyone to stay with me; I would never have dreamt of asking anyone to stay with me; even Violet had never spent more than a week at Knole: I resented invasion. Still, as Rosamund came, once she was there, I naturally spent most of the day with her, and after I had got back to England, I suppose it was resumed. I don't remember very clearly, but the fact remains that by the middle of that summer we were inseparable, and moreover were living on terms of the greatest possible intimacy.... Oh, I dare say I realized vaguely that I had no business to sleep with Rosamund, and I should certainly never have allowed anyone to find it out, but my sense of guilt went no further than that."

In June 1910 Vita met Harold Nicholson for the first time. Harold visited Vita in Monte Carlo in January 1911: "He was as gay and clever as ever, and I loved his brain and his youth, and was flattered at his liking for me. He came to Knole a good deal that autumn and winter, and people began to tell me he was in love with me, which I didn't believe was true, but wished that I could believe it. I wasn't in love with him then - there was Rosamund - but I did like him better than anyone, as a companion and playfellow, and for his brain and his delicious disposition. I hoped that he would propose to me before he went away to Constantinople, but felt diffident and sceptical about it."

In January 1912 Nicolson proposed to Vita. She refused him but under pressure from her mother, Victoria Sackville-West, Vita agreed to become engaged. As a result of the engagement, her mother gave her an allowance of £2,500 a year, of which the capital was to become hers on her mother's death.

Harold Nicholson became concerned about her relationship with Rosamund Grosvenor. He was puzzled by Rosamund's subservient attitude to Vita. He mentioned this in a letter to Vita, who replied: "It is a pity and rather tiresome. But doesn't everyone want one subservient person in your life? I've got mine in her. Who is yours? Certainly not me!" Vita later wrote in her autobiography: "It did not seem wrong to be... engaged to Harold, and at the same time so much in love with Rosamund... Our relationship (with Harold Nicholson) was so fresh, so intellectual, so unphysical, that I never thought of him in that aspect at all.... Some were born to be lovers, others to be husbands, he belongs to the latter category."

Vita Sackville-West also began a relationship with Muriel Clark-Kerr, the sister of Archibald Clark-Kerr. Muriel stayed with Vita at Knole House. Soon afterwards she wrote to Vita: "I shall not be frigid in London - why should I be, for I, too, care very much. I hated saying goodbye and did not half tell you enough how I loved being in Palais Malet, or how glad I am we both embarked on the risk. Those two days in the hills! How happy we were." Violet Keppel was also passionately involved with Vita. Violet told her: "The upper half of your face is so pure and grave - almost childlike. And the lower half is so domineering, sensual, almost brutal - it is the most absurd contrast, and extraordinarily symbolical of your Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde personality."

Rosamund Grosvenor became jealous of Vita's relationships with Harold Nicholson, Violet Keppel and Muriel Clark-Kerr. Rosamund wrote to Vita: "Oh my sweet you do know don't you. Nothing can ever make me love you less whatever happens, and I really think you have taken all my love already as there seems very little left." After one love-making session she wrote: "My sweet darling... I do miss you darling one and I want to feel your soft cool face coming out of that mass of pussy fur like I did last night."

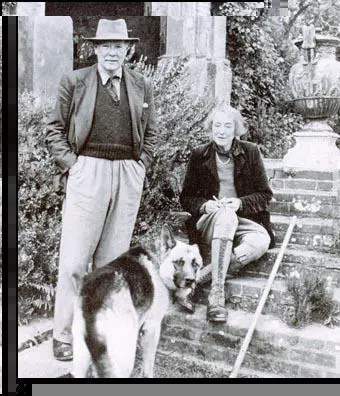

and Lionel Edward Sackville-West in 1913

Despite having several affairs with women, in October 1913 she married Harold Nicholson. He was based in Constantinople but the following year they returned to England and their first son, Lionel Benedict Nicolson, was born in August that year. They lived both in London and at Long Barn, a house near Sevenoaks. A second son was stillborn in 1915, and their last child, Nigel Nicolson, was born in London in 1917.

Vita Sackville-West published her first book Poems of East and West in 1917. She followed this with a novel, Heritage, in 1919. A second novel, The Heir (1922), dealt with her feelings about her family. Her next book, Knole and the Sackvilles (1922), covered her family history.

In April 1918 she resumed her affair with Violet Keppel. Vita later wrote: "She lay on the sofa, I sat plunged in the armchair; she took my hands, and parted my fingers to count the points as she told me why she loved me... She pulled me down until I kissed her - I had not done so for many years." The lovers travelled around Europe and collaborated on a novel, Challenge (1923), that was published in America but banned in Britain.

In March 1919 Violet Keppel wrote to Vita to explain that she was being forced to marry Denys Robert Trefusis, an officer in the Royal Horse Guards: "It is really wicked and horrible. I am losing every atom of self-respect I ever possessed. I hate myself.... I want you every second and every hour of the day, yet I am being slowly and inexorably tied to somebody else... Sometimes I am flooded by an agony of physical longing for you... a craving for your nearness and your touch. At other times I feel I should be quite content if I could only hear the sound of your voice. I try so hard to imagine your lips on mine. Never was there such a pitiful imagining.... Darling, whatever it may cost us, my mother won't be cross with you any more. I suppose this ridiculous engagement will set her mind at rest."

Violet gave in to pressure from her mother, Alice Keppel and agreed to marry Trefusis on 16th June 1919. She did so on the understanding that the marriage would remain unconsummated, and she was still resolved to live with Vita. They resumed their affair just a few days after the wedding. The women moved to France in February 1920. However, Harold Nicholson followed them and eventually persuaded his wife to return to the family home.

T. J. Hochstrasser points out: "However, this crisis in fact proved eventually to be the catalyst for Nicolson and Sackville-West to restructure their marriage satisfactorily so that they could both pursue a series of relationships through which they could fulfil their essentially homosexual identity while retaining a secure basis of companionship and affection." Sackville-West's other lovers included the journalist Evelyn Irons and Hilda Matheson, head of the BBC talks department.

Sackville-West's 2,500 line poem The Land (1926), was dedicated to her lover, the poet Dorothy Wellesley. According to Victoria Glendinning, the author of Vita: The Life of Vita Sackville-West (1983): "What Vita set out to do was to document the age-old Kentish skills and processes and the Kentish landscape, which even in the 1920s were being modified by mechanization. Her sources were not only her own daily observations but encyclopaedias of agriculture and old poems and farming treatises."

Sackville-West also became romantically involved with Virginia Woolf. Vita's nephew, Quentin Bell, later recalled: "There may have been - on balance I think that there probably was - some caressing, some bedding together. But whatever may have occurred between them of this nature, I doubt very much whether it was of a kind to excite Virginia or to satisfy Vita. As far as Virginia's life is concerned the point is of no great importance; what was, to her, important was the extent to which she was emotionally involved, the degree to which she was in love. One cannot give a straight answer to such questions but, if the test of passions be blindness, then her affections were not very deeply engaged."

Mary Garman and Roy Campbell, met Vita Sackville-West in the village post office in May 1927. She invited them to dinner with her husband, Harold Nicolson. Other guests included Leonard Woolf, Virginia Woolf and Richard Aldington. Mary wrote to William Plomer about the dinner party: "Vita Nicolson appeared, and in her wake, Virginia Woolf, Richard Aldington and Leonard Woolf. They looked to me rather like intellectual wolves in sheep's clothing. Virginia's hand felt like the claw of a hawk. She has black eyes, light hair and a very pale face. He is weary and slightly distinguished. They are not very human." In September 1927 Vita began an affair with Mary Garman. Mary wrote: "You are sometimes like a mother to me. No one can imagine the tenderness of a lover suddenly descending to being maternal. It is a lovely moment when the mother's voice and hands turn into the lover's."

Later that month, Vita Sackville-West offered the Campbells the opportunity to live in a cottage in the grounds of Sissinghurst Castle. They accepted but later Roy Campbell objected when he discovered that his wife was having an affair with Vita: "It was then that we entered the most comically sordid and silly period of our lives. We were very stupid to relinquish our precarious independence in the tiny cottage for the professed hospitality of one of the Stately Homes of England, which proved to be something between a psychiatry clinic and a posh brothel."

When Campbell was in London he told C.S. Lewis of the affair he replied: "Fancy being cuckolded by a woman!" According to Cressida Connolly: "Roy was a proud man, and this remark so punctured his pride that he returned to Kent in a towering rage. A terrified Mary took refuge at Long Barn, where Dorothy Wellesley sat up all night with a shotgun across her knees." Campbell had a meeting with Vita Sackville-West about the affair. Afterwards he wrote: "I am tired of trying to hate you and I realize that there is no way in which I could harm you (as I would have liked to) without equally harming us all. I do not dislike any of your personal characteristics and I liked you very much before I knew anything. All this acrimony on my part is due rather to our respective positions in this tangle."

It was agreed that the affair would come to an end. However, Mary Garman found the situation very difficult and wrote to Vita: "Is the night never coming again when I can spend hours in your arms, when I can realise your big sort of protectiveness all round me, and be quite naked except for a covering of your rose leaf kisses?" When Roy Campbell went into hospital to have his appendix out, the relationship resumed.

Virginia Woolf was very jealous of the affair. She wrote to Vita: "I rang you up just now to find you were gone nutting in the woods with Mary Campbell... but not me - damn you." It is believed that Woolf's novel Orlando was influenced by the affair. In October 1927 Virginia wrote to Vita: "Suppose Orlando turns out to be about Vita; and its all about you and the lusts of your flesh and the lure of your mind (heart you have none, who go gallivanting down the lanes with Campbell) - suppose there's the kind of shimmer of reality which sometimes attaches to my people... Shall you mind?"

Vita Sackville-West replied that she thrilled and terrified "at the prospect of being projected into the shape of Orlando". She added: "What fun for you; what fun for me. You see, any vengeance that you want to take will be ready in your hand... You have my full permission." Orlando, was published in October 1928, with three pictures of Vita among its eight photographic illustrations. Dedicated to Vita, the novel, published in 1928, traces the history of the youthful, beautiful, and aristocratic Orlando, and explores the themes of sexual ambiguity.

After reading the book, Mary Garman wrote to Vita: "I hate the idea that you who are so hidden and secret and proud even with people you know best, should be suddenly presented so nakedly for anyone to read about... Vita darling you have been so much Orlando to me that how can I help absolutely understanding and loving the book... Through all the slight mockery which is always in the tone of Virginia's voice, and the analysis etc., Orlando is written by someone who loves you so obviously."

Vita also wrote several sonnets about Mary. These appeared in King's Daughter (1929). After the book was published she wrote to her husband, Harold Nicolson: "It has occurred to me that people will think them Lesbian... I should not like this, either for my own sake or yours."Roy Campbell responded to the affair by writing the long satirical poem, The Georgiad. The poem caused a furore in the literary world as Campbell castigated the Bloomsbury Group. This included Vita who he described as the "frowsy poetess" in the poem:

Too gaunt and bony to attract a man

But proud in love to scavenge what she can,

Among her peers will set some cult in fashion

Where pedantry may masquerade as passion.

Campbell wrote to his friend Percy Wyndham Lewis: "Since The Georgiad (I hear) the Nicolson menage has become very Strindbergian. Each accusing the other for it and smashing the furniture about: but they are rotten to the core and I don't care about any personal harm I have done them - I take their internal disturbances as a justification of The Georgiad."

In 1930, Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson left Long Barn and purchased Sissinghurst Castle, which they set about restoring and developing into the setting for a large-scale garden. As T. J. Hochstrasser has pointed out: "Sissinghurst... the sketchy remains of a Kentish Elizabethan mansion, which they set about restoring and developing into the setting for a large-scale garden: this was a joint project where the principles of design were contributed by Nicolson and the planting schemes and maintenance by Sackville-West."

Sackville-West continued to write and published two novels, All Passion Spent (1931) and Family History (1932), and two biographical studies, St Joan of Arc (1936) and Pepita (1937). This was followed by another novel, Grand Canyon (1942), which imagined a German victory, and another long poem, The Garden (1946), won the Heinemann award for literature in 1946.

In 1948 she was appointed a Companion of Honour for her services to literature. She continued to develop her garden at Sissinghurst Castle and for many years wrote a weekly gardening column for The Observer. In 1955 she was awarded the gold Veitch medal of the Royal Horticultural Society. In her last decade she published a further biography, Daughter of France (1959) and a final novel, No Signposts in the Sea (1961).

Vita Sackville-West died of stomach cancer on 2nd June 1962. She was cremated and was buried in the Sackville family vault at Withyham, East Sussex.

Primary Sources

(1) Violet Keppel, Don't Look Round (1952)

No one had told me that Vita had turned into a beauty. The knobs and knuckles had all disappeared. She was tall and graceful. The profound, hereditary Sackville eyes were as pools from which the morning mists had lifted. A peach might have envied her complexion. Round her revolved several enamored young men.

(2) Vita Sackville-West, Autobiography (1920)

It did not seem wrong to be... engaged to Harold, and at the same time so much in love with Rosamund Grosvenor... Our relationship (with Harold Nicholson) was so fresh, so intellectual, so unphysical, that I never thought of him in that aspect at all.... Some were born to be lovers, others to be husbands, he belongs to the latter category.... It was passion that used to make my head swim sometimes, even in the daytime, but we never made love.

(3) Vita Sackville-West, Autobiography (1920)

Harold came back from Madrid at the end of that summer (1911). He had been very ill out there, and I remember him as rather a pathetic figure wrapped up in an Ulster on a warm summer day, who was able to walk slowly round the garden with me. All that time while I was "out" is extremely dim to me, very largely I think, owing to the fact that I was living a kind of false life that left no impression upon me. Even my liaison with Rosamund was, in a sense, superficial. I mean that it was almost exclusively physical, as, to be frank, she always bored me as a companion. I was very fond of her, however; she had a sweet nature. But she was quite stupid.

Harold wasn't. He was as gay and clever as ever, and I loved his brain and his youth, and was flattered at his liking for me. He came to Knole a good deal that autumn and winter, and people began to tell me he was in love with me, which I didn't believe was true, but wished that I could believe it. I wasn't in love with him then - there was Rosamund - but I did like him better than anyone, as a companion and playfellow, and for his brain and his delicious disposition. I hoped that he would propose to me before he went away to Constantinople, but felt diffident and sceptical about it.

(4) Vita Sackville-West, Autobiography (1920)

I hate writing this, but I must, I must. When I began this I swore I would shirk nothing, and no more I will. So here is the truth: I was never so much in love with Rosamund as during those weeks in Italy and the months that followed. It may seem that I should have missed Harold more. I admit everything, to my shame, but I have never pretended to have anything other than a base and despicable character. I seem to be incapable of fidelity, as much then as now. But, as a sole justification, I separate my loves into two halves: Harold, who is unalterable, perennial, and best; there has never been anything but absolute purity in my love for Harold, just as there has never been anything but absolute purity in his nature. And on the other hand stands my perverted nature, which loved and tyrannized over Rosamund and ended by deserting her without one heart-pang, and which now is linked irremediably with Violet. I have here a scrap of paper on which Violet, intuitive psychologist, has scribbled, "The upper half of your face is so pure and grave - almost childlike. And the lower half is so domineering, sensual, almost brutal - it is the most absurd contrast, and extraordinarily symbolical of your Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde personality." That is the whole crux of the matter, and I see now that my whole curse has been a duality with which I was too weak and too self-indulgent to struggle.

I really worshipped Rosamund then. We motored all over Italy, and I think it was our happiest time... I didn't go to Italy that spring, I went instead to Spain, which I looked on as partially my own country, and where in three weeks I picked up Spanish with comparative fluency. I loved Spain. I would give my soul to go there with Violet - Violet! Violet! How bloodless the Rosamund affair appears now under the glare of my affinity with Violet; how seraphic and childlike my years of marriage with Harold, when that side of me was completely submerged! I am so frightened of that side sometimes - it's so brutal and hard and savage, and Harold knows nothing of it; it would drive over his soul like an armoured chariot. He has blundered upon it once or twice, but he doesn't understand - he could no more understand it than Ben could understand algebra.

Things began to rush, after I came back from Spain. The delay over my engagement began to irritate me, and one day I wrote to Harold saying we had perhaps better give up the idea. He sent me a despairing telegram in reply, and then I scarcely know what happened inside my heart: something snapped, and I loved Harold from that day on; I think his energy in sending me a telegram impressed me, just as I was impressed when he came after me in an aeroplane when I ran away. Anyway, I wired back that everything was as before, and the letter which followed the telegram touched me greatly, for I saw by it how much he truly cared. But I continued my liaison with Rosamund. I say this with deep shame.

(5) Vita Sackville-West, letter to Harold Nicholson (April 1912)

Rosamond knows about you and me. She is very dear and sympathetic person, though she may not be particularly clever, and I am very fond of her. And she is a perfect tomb of discretion.

(6) Nigel Nicolson, Portrait of a Marriage (1973)

Her mother's fastidiousness and her father's reluctance to discuss any intimate subject with her deepened her sexual isolation. With Rosamund she tumbled into love, and bed, with a sort of innocence. At first it meant little more to her than cuddling a favourite dog or rabbit, and later she regarded the affair as more naughty than perverted, and took great pains to conceal it from her parents and Harold, fearing that exposure would mean the banishment of Rosamund. It was little more than that. She had no concept of any moral distinction between homosexual and heterosexual love, thinking of them both as "love" without qualification. When she married Harold, she assumed that marriage was love by other means, and for a time it worked.

The very existence of myself and my brother is proof of it, and there is ample evidence in the letters and diaries that for the first few years of their marriage they were sexually compatible. After 1917 it gradually became clear that their mutual enjoyment was on the wane. Lady Sackville refers in her diaries to frank conversations with Vita on the subject ("She remarks about Harold being so physically cold"). When I myself married, my father solemnly cautioned me that the physical side of marriage could not be expected to last more than a year or two, and once, in a broadcast, he said, "Being in love lasts but a short time - from three weeks to three years. It has little or nothing to do with the felicity of marriage."

Simultaneously, therefore, and without placing any great strain upon their love for each other, they began to seek pleasure with people of their own sex, and to Vita at least it seemed quite natural, for she was simply reverting to her other form of "love". Marriage and sex could be quite separate things....

She (Vita) didn't know how strong and dangerous such passion could be, until Violet replaced Rosamund. Of course she knew that "such a thing existed", but she did not give it a name, and felt no guilt about it. At the time of her marriage she may have been ignorant that men could feel for other men as she had felt for Rosamund, but when she had made this discovery in Harold himself, it did not come as a great shock to her, for she had the romantic notion that it was natural and salutary for "people" to love each other, and the desire to kiss and touch was simply the physical expression of affection, and it made no difference whether it was affection between people of the same sex or the opposite.

It was fortunate that both were made that way. If only one of them had been, their marriage would probably have collapsed. Violet did not destroy their physical union; she simply provided the alternative for which Vita was unconsciously seeking at the moment when her physical passion for Harold, and his for her, had begun to cool. In Harold's life at that time there was no male Violet, luckily for him, since his love for Vita might not have survived two rivals simultaneously. Before he met Vita he had been half-engaged to another girl, Eileen Wellesley. He was not driven to homosexuality by Vita's temporary desertion of him, because it had always been latent, but his loneliness may have encouraged this tendency to develop, since with his strong sense of duty (much stronger than Vita's) he felt it to be less treacherous to sleep with men in her absence than with other women. When he was left stranded in Paris, he once confessed to Vita that he was "spending his time with rather low people, the demi-monde", and this could have meant young men. When she returned to him, it certainly did. Lady Sackville noted in her diary, "Vita intends to be very platonic with Harold, who accepts it like a lamb.' They never shared a bedroom after that.

Harold had a series of relationships with men who were his intellectual equals, but the physical element in them was very secondary. He was never a passionate lover. To him sex was as incidental, and about as pleasurable, as a quick visit to a picture-gallery between trains. His a-sexual love for Vita in later life was balanced by affection for his men friends, by some of whom he was temporarily, but never helplessly, attracted. There was no moment in his life when love for a young man became such an obsession to him that it interfered with his work, and he had no affairs faintly comparable to Vita's. Their behaviour in this respect was a reflection of their very different personalities. His life was too well regulated to be affected by affairs of the heart, while she always allowed herself to be swept away.

(7) Vita Sackville-West, Autobiography (1920)

In 1910... Rosamund had come out to stay at Monte Carlo - invited by mother, not by me; I would never have dreamt of asking anyone to stay with me; I would never have dreamt of asking anyone to stay with me; even Violet had never spent more than a week at Knole: I resented invasion. Still, as Rosamund came, once she was there, I naturally spent most of the day with her, and after I had got back to England, I suppose it was resumed. I don't remember very clearly, but the fact remains that by the middle of that summer we were inseparable, and moreover were living on terms of the greatest possible intimacy.... Oh, I dare say I realized vaguely that I had no business to sleep with Rosamund, and I should certainly never have allowed anyone to find it out, but my sense of guilt went no further than that. Anyway I was very much in love with Rosamund.

(8) Violet Trefusis, letter to Vita Sackville-West (March 1919)

My own sweet love, I am writing this at 2 o'clock in the morning at the conclusion of the most cruelly ironical clay I have spent in my life.

This evening I was taken to a ball of some good people. Chinday had previously told all her friends I was engaged so I was congratulated by everyone I knew there. I could have screamed aloud. Mitya, I can't face this existence. I shall see you once again on Monday and it depends on you whether we shall ever see each other again.

It is really wicked and horrible. I am losing every atom of self-respect I ever possessed. I hate myself. 0 Mitya, what have you done to me? 0 my darling, precious love, what is going to become of use

I want you every second and every hour of the day, yet I am being slowly and inexorably tied to somebody else... Sometimes I am flooded by an agony of physical longing for you... a craving for your nearness and your touch. At other times I feel I should be quite content if I could only hear the sound of your voice. I try so hard to imagine your lips on mine. Never was there such a pitiful imagining.... Darling, whatever it may cost us, my mother won't be cross with you any more. I suppose this ridiculous engagement will set her mind at rest....

Nothing and no one in the world could kill the love I have for you. I have surrendered my whole individuality, the very essence of my being to you. I have given you my body time after time to treat as you pleased, to tear to pieces if such had been your will. All the hoardings of my imagination I have laid bare to you. There isn't a recess in my brain into which you haven't penetrated. I have clung to you and caressed you and slept with you and I would like to tell the whole world I clamour for you.... You are my lover and I am your mistress, and kingdoms and empires and governments have tottered and succumbed before now to that mighty combination - the most powerful in the world.

(9) Virginia Woolf, letter to Vita Sackville-West (5th December, 1927)

Should you say, if I rang you up to ask, that you were fond of me: If I saw you would you kiss me? If I were in bed would you - I'm rather excited about Orlando tonight: have been lying by the fire and making up the last chapter.

(10) Virginia Woolf, letter to Vita Sackville-West (31st January, 1928)

But I do adore you - every part of you from heel to hair. Never will you shake me off, try as you may... But if being loved by Virginia is any good, she does do that; and always will, and please believe it.

(11) Vita Sackville-West, letter to Harold Nicholson (1960)

When we married, you were older than I was, and far better informed. I was very young, and very innocent, I knew nothing about homosexuality. I didn't even know that such a thing existed, either between men or between women. You should have told me. You should have warned me. You should have told me about yourself, and warned me that the same sort of thing was likely to happen to myself. It would have saved us a lot of trouble and misunderstanding. But I simply didn't know.