John Snow

John Snow, the eldest of the nine children of William Snow and his wife, Frances Askham Snow, was born in York on 15th March 1813. His father was a labourer and the family lived in one of the poorer parts of town. (1)

According to Sandra Hempel, the "Snows... were an honest, respectable, God-fearing and industrious family with a bent for self-improvement and a strong sense of social duty. One of John's brothers went on to become a clergyman, another ran a temperance hotel, while two of his sisters opened a school." (2)

At the age of fourteen he was apprenticed to William Hardcastle, a surgeon apothecary in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. In 1831 Hardcastle and Snow attended the poor during the cholera epidemic of 1831–2, including the miners at Killingworth Colliery. (3)

It had a lasting impact on Snow and resulted in him wanting the answers to several questions: "How, exactly, did it affect the body? How was it being spread? Why were some people struck down and not others? Why did so few medical men succumb? Why had he himself emerged unscathed from the midst of so much sickness?" (4)

John Snow and Cholera

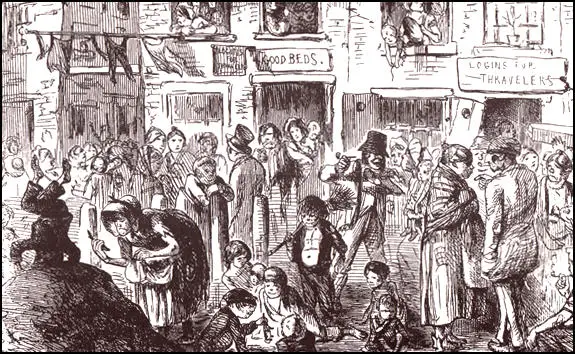

Cholera was one of the most fatal diseases in the 19th century. Nausea and dizziness led to violent vomiting and diarrhoea, "with stools turning to a grey liquid until nothing emerged but water and fragments of intestinal membrane... extreme muscular cramps followed, with an insatiable desire for water". It is estimated that 16,000 people died during the 1831-1832 epidemic. (5)

Only working-class people appeared to suffer from cholera. Stories began to circulate that doctors were spreading the disease as an excuse for getting their hands on corpses to dissect. Charles Greville, secretary to the Privy Council, noted in his diary: "The other day a Mr Pope, head of the cholera hospital in Marylebone, came to the Council Office to complain that a patient who was being removed to hospital with his own consent had been taken out of his chair by the mob and carried back, the chair broken, and the bearers and surgeon hardly escaping with their lives... In short, there is no end to the... uproar, violence, and brutal ignorance that have gone on, and this on the part of the lower orders, for whose especial benefit all the precautions are taken." (6)

Rioting broke out all over Britain. Crowds of men, women and children smashed windows at the Toxteth Park Cholera Hospital in Liverpool and pelted members of the local board of health with bricks. On 2nd September 1832, violence erupted in Manchester when a mob Swan Street Hospital, breaking down the gates and fighting a pitched battle with the police. This was as a result of a local man, John Hare, discovering that his grandson's body, who had died of cholera, had been smuggled out of the hospital by a doctor who wanted to dissect it. (7)

Snow attended sessions at the Newcastle School of Medicine in 1832–3, under John Fife. On completing his apprenticeship he became assistant, first to John Watson, general practitioner in Burnopfield, and then to Joseph Warburton, general practitioner in Pateley Bridge. (8)

Vegetarian and Temperance

During this period Snow read a pamphlet, The Return to Nature or Defence of the Vegetable Regimen (1822) by John Frank Newton. Snow was convinced by Newton's arguments that man's natural sustenance was fruit and vegetables, and thought that flesh-eating a perverse custom that caused "derangement" in the stomach and liver, an "undue impetus" to the brain, disorders of the skin and inflammation of the whole system". He also believed that all drinking water should be distilled, including that used for making tea. Newton also objected to the killing of "poor defenceless animals" and the drinking of alcohol. (9)

As a result of this pamphlet Snow became a vegetarian and joined the temperance movement and made a promise to abstain from all alcohol for life. Snow like many people dealing with problems in working-class communities, believed that alcohol was an aggravation of every social evil. "The economic waste of expenditure on drink lowers the standard of living and reduces a great many families to destitution, who, if their incomes were usefully spent, would enjoy a reasonable degree of comfort. Universal temperance would undoubtedly bring incalculable benefits and blessings." (10)

In 1836 John Snow joined the York Temperance Society and overcoming his shyness he addressed a public meeting on the subject. This was at a time when most people considered alcohol to be "highly beneficial to the health, warming and stimulating to the system, and increasing energy and physical strength... for a medical man to decry its use and refuse to prescribe it was seen at best as eccentric and by some doctors and patients as positively negligent". (11)

Snow moved to London and enrolled at the School of Medicine in Great Windmill Street School. Six months' surgical practice at Westminster Hospital completed Snow's training and he became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in May 1838. Four months later he set up in practice at 54 Frith Street, Soho, and also worked in the out-patient department of Charing Cross Hospital. (12)

Public Health Act

After the 1847 General Election, Lord John Russell became leader of a new Liberal government. The government proposed a Public Health Bill. There were still a large number of MPs who were strong supporters of what was known as laissez-faire. This was a belief that government should not interfere in the free market. They argued that it was up to individuals to decide on what goods or services they wanted to buy. These included spending on such things as sewage removal and water supplies. George Hudson, the Conservative Party MP, stated in the House of Commons: "The people want to be left to manage their own affairs; they do not want Parliament... interfering in everybody's business." (13)

Supporters of Edwin Chadwick argued that many people were not well-informed enough to make good decisions on these matters. Other MPs pointed out that many people could not afford the cost of these services and therefore needed the help of the government. The Health of Towns Association, an organisation formed by Thomas Southwood Smith, began a propaganda campaign in favour of reform and encouraged people to sign a petition in favour of the Public Health Bill. In June 1847, the association sent Parliament a petition that contained over 32,000 signatures. However, this was not enough to persuade Parliament, and in July the bill was defeated. (14)

1848 Cholera Outbreak

A few weeks later news reached Britain of an outbreak of cholera in Egypt. The disease gradually spread west, and by early 1848 it had arrived in Europe. The previous outbreak of cholera in Britain in 1831, had resulted in the deaths of over 16,000 people. In his report, published in 1842, Chadwick had pointed out that nearly all these deaths had occurred in those areas with impure water supplies and inefficient sewage removal systems. Faced with the possibility of a cholera epidemic, the government decided to try again. This new bill involved the setting up of a Board of Health Act, that had the power to advise and assist towns which wanted to improve public sanitation. (15)

In an attempt to persuade the supporters of laissez-faire to agree to a Public Health Act, the government made several changes to the bill introduced in 1847. For example, local boards of health could only be established when more than one-tenth of the ratepayers agreed to it or if the death-rate was higher than 23 per 1000. Chadwick was disappointed by the changes that had taken place, but he agreed to become one of the three members of the central Board of Health when the act was passed in the summer of 1848. (16)

In 1849 cholera killed over 50,000 people. John Snow published On the Mode of Communication of Cholera where he argued against the theory of miasmatism (a belief that diseases are caused by noxious form of air emanating from rotting organic matter). He pointed out the disease affected the intestines not the lungs. Snow suggested the contamination of drinking water as a result of cholera evacuations seeping into wells or running into rivers. (17)

Snow became a member of the Royal College of Physicians in 1850. John Snow developed a reputation as the city's leading anaesthetist and published several articles on the subject in the London Medical Gazette. (18) In April 1853, Snow gave chloroform to Queen Victoria for the birth of her son, Leopold. She wrote in her journal: "The effect was soothing, quieting and delightful beyond measure." (19)

Broad Street Pump

In August 1854 cholera cases began to appear in Soho. Snow investigated all 93 local deaths. He concluded the local water supply had become contaminated, for nearly all the victims used water from the Broad Street pump. At a nearby prison, conditions were far worse, but few deaths. Snow concluded that this was because it had its own well. On 7th September he requested the parish Board of Guardians to disconnect the pump. Sceptical but desperate, they agreed and the handle was removed. After this very few cases were reported. (20)

In 1855, Snow gave his views to a House of Commons Select Committee set up to investigate cholera. Snow argued that cholera was not contagious nor spread by miasmata but was water-borne. He advocated the government invested in massive improvements in drainage and sewage. It has been claimed that his research "played some part in the investment by London and other major British cities in new main drainage and sewage systems." (21)

John Snow had poor health throughout his life and on 10th June 1858, he suffered a stroke. His condition deteriorated and he died on 16th June at his home at 18 Sackville Street, Piccadilly, London. Post-mortem examination showed evidence of old pulmonary tuberculosis and advanced renal disease. (22)

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Greville, diary entry (1st April, 1832)

I have refrained for a long time from writing down anything about the cholera because the subject is intolerably disgusting to me, and I have been bored past endurance by the perpetual questions of every fool about it. It is not, however, devoid of interest. In the first place, what has happened here proves that the people of this enlightened, reading, thinking, reforming nation are not a whit less barbarous than the serfs in Russia, for precisely the same prejudices have been shown here that were found at St Petersburg and at Berlin.

The other day a Mr Pope, head of the cholera hospital in Marylebone, came to the Council Office to complain that a patient who was being removed to hospital with his own consent had been taken out of his chair by the mob and carried back, the chair broken, and the bearers and surgeon hardly escaping with their lives... In short, there is no end to the... uproar, violence, and brutal ignorance that have gone on, and this on the part of the lower orders, for whose especial benefit all the precautions are taken.

(2) Stephanie J. Snow, John Snow : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

The Broad Street cholera outbreak began on 31 August and claimed over 500 lives in ten days. At its start Snow began to consider the local water supplies, and he suspected contamination of the water pump in Broad Street. He took a list of deaths from cholera from the General Register Office and mapped the location of these deaths around the locality. His analysis showed that the majority of deaths had taken place in the vicinity of the Broad Street pump and he presented this evidence to the local board of guardians. The handle of the Broad Street pump was removed, but although this incident has been recorded as the dramatic halt of the outbreak this was not the case, as the intensity of the epidemic was already receding. What is important about the event is that Snow's evidence succeeded in forcing local government action. A cholera inquiry committee was eventually set up by the parish to investigate the outbreak further, and with the help of Edwin Lankester and Henry Whitehead, the local curate, the original source of contamination of the water pump at the commencement of the outbreak was identified.

Snow's interest in water supplies to south London stemmed from the 1849 epidemic, when he noted that cholera fatality rates were particularly high in the areas supplied by the Lambeth and the Southwark and Vauxhall water companies. In 1852 the Lambeth company moved its waterworks to Thames Ditton, thus obtaining a supply of water quite free from the sewage of London. Snow undertook an investigation to calculate the number of deaths from cholera per 10,000 houses during the first seven weeks of the 1854 epidemic. He recognized the scope presented by such an epidemiological experiment, as it would include 300,000 individuals of both sexes, of varying ages and occupations, and from all social classes. His initial conclusions found that 38 houses out of the 44 where deaths from cholera had occurred were supplied with water by the Southwark and Vauxhall water company and he communicated these facts to William Farr. Farr ordered his registrars of all south districts of London to make a return of the water supply for all houses where there had been a death from cholera. The conclusion of this investigation was that the mortality rate for the houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall company was between eight and nine times greater than houses supplied by the Lambeth company. This investigation was an excellent demonstration of collaborative working between practitioners in medicine and those in the newly emerging social sciences. Snow was unable to obtain the proof he required through traditional medical science, so he turned to the new public health data sources to provide evidence for his argument.

(3) John Simon, Fifth Annual Report to the City of London (1853)

The giant error of London is its present system of drainage. Probably in considerable parts of the metropolitan area, house-drainage is extensively absent: probably in considerable parts, the sewers, from the nature of their construction, are very doubtful advantages to the districts they traverse: but the evil, before all others, to which I attach importance in relation to the present subject, is that habitual empoisonment of soil and air which is inseparable from our tidal drainage. From this influence, I doubt not, a large proportion of the metropolis has derived its liability to Cholera. A moment's reflection is sufficient to show the immense distribution of putrefactive dampness which belongs to this vicious system. There is implied in it that the entire excrementation of the metropolis (with the exception of such as, not less poisonously, lies pent beneath houses) shall sooner or later be mingled in the stream of the river, there to be rolled backward and forward amid the population; that, at low water, for many hours, this material shall be trickling over broad belts of spongy bank which then dry their contaminated mud in the sunshine, exhaling foetor and poison; that at high water, for many hours, it shall be retained or driven back within all lowlevel sewers and house-drains, soaking far and wide into the soil, or leaving putrescent deposit along miles of underground brickwork, as on a deeper pavement. Sewers which, under better circumstances, should be benefactions and appliances for health in their several districts, are thus rendered inevitable sources of evil. During a large proportion of their time they are occupied in retaining or re-distributing that which it is their office to remove. They furnish chambers for an immense faecal evaporation; at every tide which encroaches on their inward space, their gases are breathed into the upper air - wherever outlet exists, into houses, foot-paths, and carriage-way.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

References

(1) Stephanie J. Snow, John Snow : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(2) Sandra Hempel, The Medical Detective (2006) page 70

(3) Stephanie J. Snow, John Snow : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(4) Sandra Hempel, The Medical Detective (2006) page 83

(5) Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind (1997) page 403

(6) Charles Greville, diary entry (1st April, 1832)

(7) Sandra Hempel, The Medical Detective (2006) page 78

(8) Stephanie J. Snow, John Snow : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(9) John Frank Newton, The Return to Nature or Defence of the Vegetable Regimen (1822)

(10) Philip Snowden, An Autobiography (1934) page 66

(11) Sandra Hempel, The Medical Detective (2006) page 73

(12) Stephanie J. Snow, John Snow : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(13) George Hudson, speech in the House of Commons (3rd July 1847)

(14) Michael Flinn, Public Health Reform in Britain (1968) page 31

(15) Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind (1997) page 411

(16) Michael Flinn, Public Health Reform in Britain (1968) page 32

(17) John Snow, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera (1849)

(18) Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind (1997) page 412

(19) Queen Victoria, journal entry (7th April, 1853)

(20) Michael Flinn, Public Health Reform in Britain (1968) page 32

(21) Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind (1997) page 413

(22) Stephanie J. Snow, John Snow : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)