Kitty Bowler

Kitty Bowler, the daughter of Robert Bonner Bowler and Charlotte Everett Miller, was born in Plymouth, Massachusetts, on 10th February 1908. She was related to Edward Everett, who served as Secretary of State in the government of Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War.

After attending Bryn Mawr College, where she studied economics and politics, she volunteered to work with the League Against War and Fascism and the International Labour Defence. She wrote at the time: "I don't like Fascism. Liberalism is as seductive and untrustworthy as a mistress. In these tumultuous days I prefer a good trustworthy companion, who'll stick by me thick and thin. I want something that works. So it will have to be one one the brands of socialism."

In 1936 she visited the Soviet Union where she started an affair with the journalist Walter Durante, who was working for the New York Times. Later that year she travelled to Spain. A friend described her as "an arresting young woman of twenty-eight of less than medium height, slender, with large brown eyes and a short tousled bob, not unlike Amelia Earhart".

In August 1936 Harry Pollitt arranged for Tom Wintringham to go to Spain to represent the Communist Party of Great Britain during the Civil War. While in Barcelona in September Bowler met Wintringham. She later recalled: "I wandered over to the cafe Rambla feeling desolate and forlorn. Like the story book waif, who peeks through frosted panes at the happy families gathered round the fireside, I eyed the little group at a corner table... All conversation stopped. Blankly and coldly they looked at me as only the English can. Then a soft-voiced bald man touched my arm: "You must join us." Soon afterwards Bowler began an affair with Wintringham.

Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, who was with Tom Wintringham at the time, later pointed out: "Kitty was a neat, active, progressive, American girl who had nipped across from France to see what was going on and maybe to make a name for herself." Wintringham's biographer, Hugh Purcell, wrote in Last English Revolutionary (2004): "While Tom and Kitty were falling in love they were also exploiting each other. She used him to guide her apprentice journalism; he used her as unofficial secretary and messenger."

Kitty wrote to Tom: "You took a somewhat undirected little lost girl and made a person of her. I love you, love you, all of you, your long tall body, your sweet steadying voice, your brains and good sense mixed with good emotion." Tom replied: "You know a good deal about giving a man a good time, and then some! The total effect on morale of my 24 hours leave was A1 Magnificent. I'm on top of the world."

Ralph Bates, a writer based in Spain, sent a highly critical report to Harry Pollitt about Wintringham and his relationship with Kitty Bowler. "Everyone here was very disappointed with Comrade Wintringham. He showed levity in taking a non-Party woman in whom neither the PSUC nor the CPGB comrades have any confidence to the Aragon front. We understand this person was entrusted with verbal messages to the Party in London. We are asked to send messages to Wintringham through this person rather than the Party headquarters here. The Party has punished members for far less serious examples of levity than this."

Kitty Bowler arrived back in London with a message from Wintringham. Kenneth Sinclair Loutit was in the CPGB offices at the time: "She bounced in as the dawn, looking as bright as a new dollar and bringing an unaccustomed waft of Elizabeth Arden fragrance through the dusty entrance." Bowler asked for Harry Pollitt but he was out and was instead seen by Rajani Palme Dutt and John Campbell. Loutit commented: "She saw Pollitt later but the damage was done. Tom had sent back a bourgeois tart - a great talker, some said she clearly had Trotskyite leanings... It must not be forgotten that Tom had a wife of deadly respectability and unimpeachable Marxist propriety."

Kitty Bowler claimed that she asked Harry Pollitt to send Wintringham home. He told her to "tell him to get out of Barcelona, go up to the front line, get himself killed to give us a headline.... the movement needs a Byronic hero."

When she returned to Spain she joined the PSUC English-speaking radio service in Barcelona. In December 1936 she joined the UGT and wrote to her mother: "I've gotten in with the editor of a Spanish newspaper and am getting all sorts of inside news and rushed around in cars." Her new contacts resulted in being given an assignment from The Toronto Star.

In January 1937 Kitty Bowler travelled to Albacete where she was detained and interviewed by André Marty. "Behind a rolltop desk sat an old man with a first class walrus moustache. He was sleepy and irritable and had pulled a coat on over his pyjamas. He reminded me of a petty French bureaucrat. Perhaps that was just as well. To my surprise my mass of Spanish papers did not interest him in the least. Even my U.G.T. card and pass were thrown back in my face, contemptuously. My past was all that interested him, but I was sure it would all be cleared up in the morning when Mac and Tom came over. ... At the end of an hour he read out the charges and they shocked me out of my certainty. 1) Travelled from Albacete to Madrigueras by truck without a pass. 2) Penetrated into a military establishment. 3) Interested yourself into the functioning (bad) of machine guns. 4) Visited Italy and Germany in 1933. Therefore you are a spy."

Tom Wintringham attempted to protect Kitty by contacting André Marty. He then told her: "You impressed Marty as very, very strong, very clever, very intelligent. Although this was said as a suspicious point against you - women journalists should be weak and stupid - I got a jump of pride from these words." After being interviewed for three days and nights Kitty was expelled from Spain as a spy.

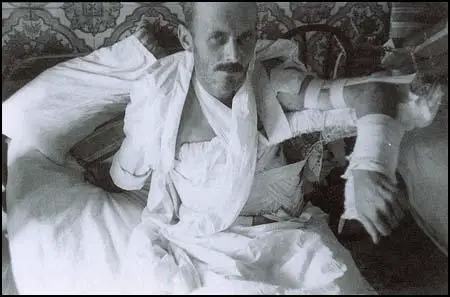

On 13th February, 1937, Tom Wintringham was hit in the thigh while trying to organise a bayonet charge. Fred Copeman later commented that George Aitkin and himself found Wintringham sitting behind an olive tree: "Well, we knew he shot himself." This is refuted by Aitkin who confirmed that he had been shot by the enemy.

The Daily Mail claimed on 20th February 1937 that many of the so-called volunteers had been press-ganged into the British Battalion and that at Madrigueras those who did not want to fight "were lined up and shot; the remainder like cattle were then driven to slaughter... commanded by an Englishman named Wintringham." As a result of this article, Wintringham later won a libel action against the newspaper.

Kitty Bowler visited him in Pasionaria Military Hospital and discovered he was suffering from typhoid and a form of septicaemia. Patricia Darton, a nurse with the International Brigades, later commented: "I poked around with a pair of scissors and found he had a lot of pus in his wounds which had been sewn up too tightly. And that was it; he got better very quickly."

Elizabeth Wintringham wrote to Kitty to thank her for looking after Tom. "How perfectly splendid you have been! Is Tom sensible at all, or rambling all the time? If it's possible please give him my love and Oliver's. If he seems inclined to worry about Millie and Lesley assure him they are being looked after. You may know who they are. I shall hope very much to meet you someday before long."

Charlotte Everett Bowler was less pleased with her daughter looking after Tom. She wrote: "It's all very charming and delightful for you; you gain almost everything. For my very dear child it's pretty tragic any way you look at it. I resent her giving her all - her mind, body and spirit - on such insecure grounds. Naturally I am distressed."

Tom replied: "I owe my life to your daughter, and a great deal more than just going on living... But there is very little I can say to reassure you because security does not exist. If I could have married Kitty I would have done so; if I can, I will. But better this might be in the future, rather than tie her to a blind or crippled husband."

While Tom Wintringham was in Pasionaria Military Hospital he was visited by William Gallacher who had an order from the Communist Party of Great Britain: "The Party Order that I should leave Kitty was delivered to me by a very embarrassed Bill Gallacher while she was still nursing me through typhoid before I was strong enough even to stand."

Kitty was arrested by the Comintern police on 2nd July 1937 and she was expelled from Spain. She moved back to the United States. On 17th July 1937 Tom wrote: "My dear, the party, our party, yours and mine, is sometimes hard on individuals. But look at the job of work it does as a whole and there's nothing like it on earth or ever has been."

Tom Wintringham rejoined the XV Brigade on 18th August 1937 as a staff officer. He was immediately sent to the Aragon front and during the Battle of Belchite on 24th August he was shot in the shoulder while attempting to capture Quinto. He wrote to Kitty: "A bullet through the soldier, cracking a bone or so. Lost a lot of blood. I love you. Being away from you hurts more than silly bullets."

Dr Alex Tudor-Hart, a member of the CPGB who was providing medical care for the British Battalion, told him that his shoulder bone had splintered and this extended almost down to his elbow. This became infected and after two operations in Spain he was sent home to England. Kitty immediately left the United States and the two of them set-up home in a flat in York Street, London.

Tom's younger sister, Margaret, wrote a letter to Kitty: "I'm afraid I think it's rather a pity that you have come to London. I have grown to love and admire Elizabeth - I think she is a very good person... I know that the Party was pretty annoyed with him some time ago and the Millie-Elizabeth situation has been a source of embarrassment to Harry Pollitt. One or two people back from Spain have spoken of Tom's affairs as a joke, which is intolerable. So you see I must take sides against you."

Tom's younger sister, Margaret, wrote a letter to Kitty: "I'm afraid I think it's rather a pity that you have come to London. I have grown to love and admire Elizabeth - I think she is a very good person... I know that the Party was pretty annoyed with him some time ago and the Millie-Elizabeth situation has been a source of embarrassment to Harry Pollitt. One or two people back from Spain have spoken of Tom's affairs as a joke, which is intolerable. So you see I must take sides against you."

Margaret Wintringham also wrote to Tom Wintringham about his behaviour: "You simply can't get away with all this irresponsibility. Granted you have to abandon two sets of families, you might at least spare them minor anxieties. You could spare Elizabeth the small humiliation of ringing up the hospital and being asked if she would like to speak to Mrs Wintringham. You know you have a strong faculty for inspiring affection but I repeat, you can't get away with things like this."

Tom refused to go back to live with Elizabeth Wintringham and continued to live with Kitty Bowler at 30 Arundel Square, London. He also began work on English Captain, a book on his experiences of the Spanish Civil War.

At a meeting of the Comintern in March 1938, André Marty confirmed that Bowler was a "Trotskyite spy". Wintringham was contacted and told that if he did not leave Bowler he would be expelled from the Communist Party of Great Britain. According to a Politburo meeting on 18th May 1938: "He (Wintringham) refused to accept discipline in relation to a personal question not considered to be in the interests of the Party." The case was put into the hands of Rajani Palme Dutt who decided that Wintringham should definitely be expelled from the CPGB. The Daily Worker printed the verdict on 7th July 1938.

Wintringham received support from people such as Bob Stewart and Harry Pollitt but they were unable to change the mind of Rajani Palme Dutt who carried out the orders of Joseph Stalin and the Soviet government.

At the beginning of Second World War, Kitty worked for left-wing newspapers such as the People's Independent. In 1939 Elizabeth Wintringham and her son Oliver left London to live in Derbyshire. Oliver attended Abbotsholme School. On 12th February 1940 Elizabeth petitioned for divorce.

Their friends during this period included Storm Jameson, Naomi Mitchison, Stephen Swingler and Pearl Binder. However, Anne Swingler pointed out: "She (Kitty) certainly didn't like pretty young girls around. She was thin, with wild dark hair and an awkward manner. I thought she was scatty, an endless talker, but bossy too. She was very possessive of Tom. People avoided her." Anne liked Tom a great deal: "He spoke with such authority but he was gentle and charming too. Quite a lady's man! And he thrived on women's company."

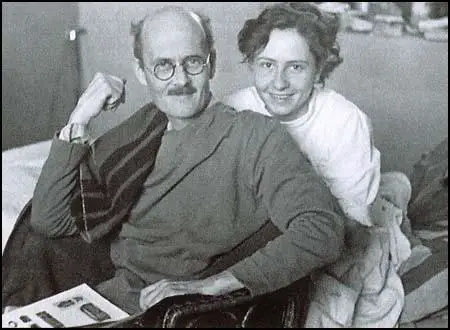

Tom Wintringham married Kitty at Dorking Registry Office on 25th January 1941. Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, a friend since the Spanish Civil War, was the main witness.

J. B. Priestley and a group of friends established the 1941 Committee. One of its members, Tom Hopkinson, later claimed that the motive force behind the organization was the belief that if the Second World War was to be won "a much more coordinated effort would be needed, with stricter planning of the economy and greater use of scientific know-how, particularly in the field of war production." Kitty and Tom Wintringham joined and so did Edward G. Hulton, Kingsley Martin, Richard Acland, Michael Foot, Peter Thorneycroft, Thomas Balogh, Richie Calder, Tom Wintringham, Vernon Bartlett, Violet Bonham Carter, Konni Zilliacus, Tom Driberg, Victor Gollancz, Storm Jameson, David Low, David Astor, Thomas Balogh, Richie Calder, Eva Hubback, Douglas Jay, Christopher Mayhew and Richard Titmuss.

In December 1941 the committee published a report that called for public control of the railways, mines and docks and a national wages policy. A further report in May 1942 argued for works councils and the publication of "post-war plans for the provision of full and free education, employment and a civilized standard of living for everyone."

Later that year Richard Acland and J. B. Priestley and other members of the 1941 Committee established the socialist Common Wealth Party. The party advocated the three principles of Common Ownership, Vital Democracy and Morality in Politics.

Kitty was on the National Committee of the Common Wealth Party (CWP) and during this period came into conflict with Richard Acland. He accused her of having a "more chaotically disorderly brain than anyone I've ever met... you are wholly incapable of holding an organised part in any discussion or argument." Kitty replied that the CWP "is disintegrating because of attempts to turn it into an autocratic pseudo-religious body with fascist tendencies."

After the war Tom and Kitty lived in Pear Trees, at Brick End, Broxted. On 26th January 1947, Kitty gave birth to Benjamin Rhys Wintringham. In 1948 they moved to Edinburgh. Tom continued to work as a journalist and their income was supplemented by a trust fund that had been set-up in New York City by Kitty's family. Tom wrote to his son Oliver Wintringham: "Happiness, I feel superstitiously, should never be mentioned in a world such as this that you inherit. Then sometimes it may creep up on you without noticing you are there; and if you politely do not stare at it, may remain about the place."

Tom Wintringham died while helping with the harvest on his sister's farm at Searby Manor in Lincolnshire on 16th August 1949. The post-mortem showed that Tom died of a ruptured aneurism of the right coronary artery. Kitty wrote to her friend, Rhys Caparn: "When they finally allowed me to go back and see him after the post mortem. I went to see his hands, hands don't die. And then it was the face that was so wonderful - not my private Tom, but all the fine strength of him - the man who could and did - and so many believed would do again and he was about ready to - could lead and inspire men." The funeral took place at Leeds Crematorium three days later.

In the early 1950s Kitty took her son to live with her mother in Hawaii. However, she felt uncomfortable in a country enduring McCarthyism and she returned to England.

Kitty Wintringham killed herself in 1966. She wrote in her suicide note to Oliver Wintringham that life without his father was not worth living.

Primary Sources

(1) Kitty Bowler, letter (September 1936)

I wandered over to the cafe Rambla feeling desolate and forlorn. Like the story book waif, who peeks through frosted panes at the happy families gathered round the fireside, I eyed the little group at a corner table. I saw a "moving forest of bare knees". Only England could produce anything so incredibly tall and fresh as those boys. Shy but desperate I approached. All conversation stopped. Blankly and coldly they looked at me as only the English can. Then a soft-voiced bald man touched my arm: "You must join us."

Relaxing gradually I realised I was talking to a gifted conversationalist, cultured, intelligent, witty. I liked this man's mind and the amusing twist he would give a phrase. But I was puzzled. This quiet literary individual wasn't my idea of a military man. "That's Tom Wintringham", I was told, "the author of a book on Marxist military strategy. He's a big shot in the English Communist Party, but he's an old sweetie."

(2) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, Very Little Luggage (2009)

A few days later the first drip-dry cotton any of us had ever seen was hanging in the Grañen hospital garden. It belonged to an American free-lance journalist called Kitty. She dressed smartly and neatly in practical "sporty" clothes. She had come to have a look at us, because Tom Wintringham had told her that there was a good story waiting to be written on the Huesca front. She later became Kitty Wintringham; by 1938 their coming together was to result in Tom being expelled from the British Communist Party.

Tom's fault was maintaining personal relations with elements considered undesirable by the CPGB which dated from the very week of my baptism of fire. It was the arrival of Kitty that did it. Tom was only fifteen years older than me, but I had read very widely and was in some ways older than my own twenty three. This meant that we could talk together on a plane that helped us both. Tom's conclusions, after a few weeks of Spain, were clear-cut and definite. In war, as in boxing, amateurs can only win a fight against professionals by scoring a knock-out in an early round. In the case of Spain, the amateurs were not making a full-time job of fighting the enemy; they were taking time off for fighting each other. The rivalry of PSUC and the FAI was ruinous. The foreign volunteers were tragically amateur. Who could imagine that the Thaelmann Centuria Germans were from a great military nation? They had good morale, they were risking their lives, but their lines were a slum and all military initiative was left to the enemy. Tom wrote a paper in September 1936 suggesting that international volunteers must show real military expertise. To use foreign volunteers for their journalistic impact on non-Spanish public opinion might be politically useful, but such amateurs would not change the military position. He wanted the Central Committee of the British Communist Party to reach a mature appreciation of the military position because he thought that the working-class movement's current reaction to the Civil War was altogether lacking in realism.

For Tom Winteringham, the Popular Front should be showing professionalism in military matters. International military assistance should be as professional as was the medical assistance. He was asking for an International Brigade of ex-servicemen. He got Kitty to take his report back to King Street (the CPGB H/Q) where she was to put it directly into the hands of Harry Pollitt, the Secretary General of the British Communist Party. The risk of mailing it from Spain was certainly far too great, but the choice of Kitty as a courier for this 'high security' tract was in fact a tactical error. Kitty was a college-girl archetype - leggy with a swinging walk, bottom in and bust out even though she did not have much of either. Her quick-fire, clear, zesty, American speech came out of a neatly lipsticked mouth which was set in a young self-confident face. I suppose she was then just less than 30 years old. So Kitty hurtled back to London arriving at Victoria Station early one morning feeling pretty beat up. She wanted to do a good job for Tom. Her background told her that a beat-up girl does not get as good a hearing as one who looks on top of the world. For a good hearing in King Street in 1936 this was a wrong. Led by her mistaken intuition, Kitty went straight from Victoria Station to the Bond Street Elisabeth Arden and gave herself the works: sauna, full facial, hairdo, and no doubt put on a clean drip-dry swirly skirt.

On the top of her form, she took King Street by storm. She certainly laid them all flat, but with the wrong emotions. A month or so later I had her side of the tale; she said that only one person in King Street knew how to smile but he worked with a sour-puss. They were glad to get Tom's report, but they did not seem to want any discussion. She also had taken the chance to tell them that they ought to make better financial arrangements for Tom in Spain, as he was quite evidently short of money.

A secondary source later indicated to me that Tom's lawful wedded wife, a party-member of standing, had been in King Street on the morning that Tom's dispatch was delivered. Kitty's mere presence, to say nothing of her Elisabeth Arden aura, must have served to confirm all the earlier traveller's tales. In those days a certain greyness, a quakerish sobriety, an evident renunciation of the superfluous, was reckoned as becoming to females with Party links. Poor Kitty must have exemplified the very licentiousness of the class-enemy, the bourgeoisie. Tom had certainly chosen Kitty as courier because he knew that she would get there, through Hell or high-water, without fail. What he failed to see was that her appearance, and her frank drive, would serve to weaken the force of his dispatches. He had not yet come to grips with Stalinist mediocracy; a characteristic so well demonstrated by O'Donnel.

(3) Kenneth Sinclair Loutit, letter to David Fernbach (1978)

Tom was carrying a knap-sack and wore a trench coat; the sort of stuff that Millets sold in their army surplus stores. He looked battered but had a good smile and a small subaltern moustache below his bald head. His approach to me was characteristic, direct, friendly, pragmatic, constructive. "How can your presence be explained?" I asked. "Look," said Tom, "the Party as you saw in Paris is the brain, heart and guts of the Popular Front and it's even more so in Spain. Unless the unit is right with the Party you'll be lost." He went on to suggest that his party affiliations should be neither concealed nor advertised...

He (Wintringham) was helpful and kind in great things and small. To be with a warmly human Marxist who was also a cool soldier made it possible for me possible for me to find the beginning of the path and I count him one of the best friends I ever had. I understood exactly what Kitty saw in him. He still carried some of the hubris of that gallant generation that bore the weight of 1914-18....

She bounced in as fresh as the dawn, looking as bright as a new dollar and bringing an unaccustomed waft of Elizabeth Arden fragrance through the dusty entrance. She asked for Harry Pollitt. He was out at the time but she was received by Jack [J.R.] Campbell and Palme-Dutt. She saw Pollitt later but the damage was done. Tom had sent back a bourgeois tart - a great talker, some said she clearly had Trotskyite leanings - Ernie Brown whom I met a year later said "Eeh lad, what d'y expect; smelling like a whorehouse and dressed like for the races!" It must not be forgotten that Tom had a wife of deadly respectability and unimpeachable Marxist propriety who went about with the refrain "I hesitate to believe appearance and I do not wish to believe that Tom has sold-out".

(4) Kitty Bowler, letter (January 1937)

Behind a rolltop desk sat an old man with a first class walrus moustache. He was sleepy and irritable and had pulled a coat on over his pyjamas. He reminded me of a petty French bureaucrat. Perhaps that was just as well. To my surprise my mass of Spanish papers did not interest him in the least. Even my U.G.T. card and pass were thrown back in my face, contemptuously. My past was all that interested him, but I was sure it would all be cleared up in the morning when Mac and Tom came over. ... At the end of an hour he read out the charges and they shocked me out of my certainty. 1) Travelled from Albacete to Madrigueras by truck without a pass. 2) Penetrated into a military establishment. 3) Interested yourself into the functioning (bad) of machine guns. 4) Visited Italy and Germany in 1933. Therefore you are a spy.

(5) Hugh Purcell, Tom Wintringham (2004)

When Kitty was released she was sentenced without her knowledge to be expelled from Spain. This order was not handed to her until the following July, possibly because of the lack of evidence against her but, more likely, because she was at the time a member of the foreign press corps, however tenuously. Why was she condemned as a spy when clearly she was, at worst, a foolhardy and gabby young woman? Albacete was in a state of spy fever. Marty was a paranoid psychopath and a misogynist for whom, according to Tom, a young woman travelling without her husband was ipso facto up to no good. Marty neither trusted the character assessments of Spaniards or Germans (Jorge S.) when it came to issuing passes, nor did he follow the concept of presumed innocence until found guilty. But what made it harder for both Marty and, indeed, Wintringham was that neither Wilfred McCartney nor Peter Kerrigan was prepared to intervene. McCartney was particularly unsympathetic, judging pithily that Tom's problems were "skirt not line".

It was only years later that Tom gave his version of what happened, having kept quiet about it, he said, out of deference to the Party. But in 1941 a manuscript written by McCartney that referred to the incident, coupled with an off-hand remark McCartney made at a dinner in Kitty's presence - "I would not have minded if she had been shot" - so incensed Tom that he gave his side of the story. In fact, he threatened the publisher Victor Gollancz he would sue for libel if he turned McCartney's manuscript into a book. It was withdrawn.