John J. Williams

John James Williams, the ninth of eleven children, was born in Frankford, Sussex County, Delaware, on 17th May, 1904. In 1922 he moved to Millsboro and became involved in the grain business. Two years later he married Elsie Steele.

John Williams and his brother, Preston Williams, established the Millsboro Feed Company. In 1946, he served on the Millsboro Town Council.

A member of the Republican Party, Williams was elected to the Senate in 1946. Soon after arriving in Washington he began investigating political corruption. He was especially concerned about corruption in the Internal Revenue Service. By 1948 he had exposed the illegal activities of two hundred employees of the Treasury Department.

In 1952 it was suggested that John Williams should be the running mate for Republican Presidential nominee Dwight D. Eisenhower. However, Williams announced he did not want the post as he wanted to retain his independence.

Instead, Williams concentrated on his investigations of corruption. He became known as the "Sherlock Holmes of Capitol Hill" and the "Conscience of the Senate". In 1958 he contributed to the downfall of Sherman Adams, Eisenhower's chief of staff. During a 15 year period his investigations resulted in over 200 indictments and 125 convictions.

In 1962 Williams began to investigate the activities of Bobby Baker, a close associate of the Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. His fellow senator, Carl Curtis, later commented: "Williams was a man beyond reproach, sincere and intelligent and dedicated. During his service in the Senate he was rightly referred to as the conscience of the Senate. He was an expert investigator, tenacious and courageous. Senator Williams became the prime mover in bringing about the investigation of Baker."

Bobby Baker had established the Serve-U-Corporation with his friend, Fred Black, and mobsters Ed Levenson and Benny Sigelbaum. The company was to provide vending machines for companies working on federally granted programs. The machines were manufactured by a company secretly owned by Sam Giancana and other mobsters based in Chicago.

Rumours began circulating that Bobby Baker was involved in corrupt activities. Although officially his only income was that of Johnson's aide, he was clearly a very rich man. Baker was investigated by Attorney General Robert Kennedy. He discovered Baker had links to Clint Murchison and several Mafia bosses. Evidence also emerged that Lyndon B. Johnson was also involved in political corruption. This included the award of a $7 billion contract for a fighter plane, the F-111 to General Dynamics, a company based in Texas. On 7th October, 1963, Baker was forced to leave his job. Soon afterwards, Fred Korth, the Navy Secretary, was also forced to resign because of the F-111 contract.

According to Anthony Summers (Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover) Bill Thompson asked Bobby Baker if he would arrange a meeting between Ellen Rometsch and John F. Kennedy. Baker later said that: "He (Kennedy) sent back word it was the best time he ever had in his life. That was not the only time. She saw him on other occasions. It went on for a while."

J. Edgar Hoover discovered that Kennedy was having a relationship with Ellen Rometsch. In July 1963 Federal Bureau of Investigation agents questioned Romesch about her past. They came to the conclusion that she was probably a Soviet spy. Hoover actually leaked information to the journalist, Courtney Evans, that Romesch worked for Walter Ulbricht, the communist leader of East Germany. When Robert Kennedy was told about this information, he ordered her to be deported.

The FBI had discovered that there were several women at the Quorum Club, run by Bobby Baker, who had been involved in relationships with leading politicians. This included both John F. Kennedy and Robert Kennedy. It was particularly worrying that this included Maria Novotny and Suzy Chang. This was a problem because they had both initially came from communist countries and had been named as part of the spy ring that had trapped John Profumo, the British war minister, a few months earlier. President Kennedy told J. Edgar Hoover that he "personally interested in having this story killed".

Hoover refused and leaked the information to Clark Mollenhoff. On 26th October he wrote an article in the Des Moines Register claiming that the FBI had "established that the beautiful brunette had been attending parties with congressional leaders and some prominent New Frontiersmen from the executive branch of Government... The possibility that her activity might be connected with espionage was of some concern, because of the high rank of her male companions". Mollenhoff claimed that John Williams "had obtained an account" of Rometsch's activity and planned to pass this information to the Senate Rules Committee, the body investigating Baker.

The following day Robert Kennedy sent La Verne Duffy to West Germany to meet Ellen Rometsch. In exchange for a great deal of money she agreed to sign a statement formally "denying intimacies with important people." Kennedy now contacted Hoover and asked him to persuade the Senate leadership that the Senate Rules Committee investigation of this story was "contrary to the national interest". He also warned on 28th October that other leading members of Congress would be drawn into this scandal and so was "contrary to the interests of Congress, too".

J. Edgar Hoover had a meeting with Mike Mansfield, the Democratic leader of the Senate and Everett Dirksen, the Republican counterpart. What was said at this meeting has never been released. However, as a result of the meeting that took place in Mansfield's home the Senate Rules Committee decided not to look into the Rometsch scandal.

John Williams also revealled that Bobby Baker had bought a house for Nancy Carole Tyler. Baker later commented in his autobiography, Wheeling and Dealing: Confessions of a Capitol Hill Operator: "Senator Williams was happy to announce such stories to the press. He also presumably enjoyed breaking the story of how I'd bought the $28,000 town house Carole Tyler lived in... It was a nice enough house, but the furnishings were vastly inflated as to worth and style, as were the reports which sounded as if orgies occurred there with the setting of the sun. There was an embarrassment involved, however. I had incorrectly and improperly listed Carole Tyler as my cousin when I applied for the loan, in order to satisfy the Federal Housing Authority's regulation that anyone buying an FHA-underwritten home must either live in it or have a relative living in it."

On 3rd October, 1963, Williams went to Senator Mike Mansfield, the majority leader, and to Senator Everett Dirksen, the minority leader, and arranged for them to call Bobby Baker before the leadership at a closed meeting on 8th October. Baker never appeared before the Senate's leadership: the day before his scheduled appearance he resigned his post.

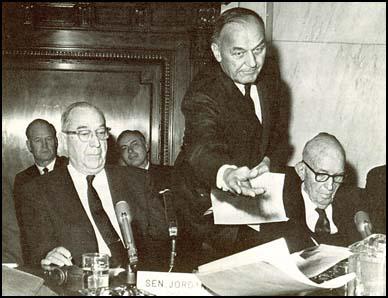

Williams now introduced a resolution calling upon the Committee on Rules and Administration to conduct an investigation of the financial and business interests and possible improprieties of any Senate employee or former employee. On 10th October 10, the Senate adopted this resolution. The committee was made up of three Republican members, Carl Curtis, John Sherman Cooper and Hugh Scott and six Democrats, B. Everett Jordan, Carl Hayden, Claiborne Pell, Joseph S. Clark, Howard W. Cannon and Robert C. Byrd.

Williams then provided information about Bobby Baker's involvement with the Serve-U-Corporation, the Mortgage Guaranty Insurance Corporation and the Haitian-American Meat Provision Company. He also raised the issue of Ellen Rometsch and Nancy Carole Tyler being involved in sex parties that were held at Baker's house for members of Congress. Williams also suggested that the committee should look into the transactions between Baker and Don B. Reynolds and the selling of insurance to Lyndon B. Johnson.

Throughout these hearings, the Republican members of the repeatedly tried to have Walter Jenkins called as a witness. As Carl Curtis pointed out: "Jenkins had been employed by Johnson for years. It was well established that he had handled many of Johnson's business concerns. The information given to the Committee by Reynolds clearly conflicted with the memorandum to which Jenkins had subscribed... Why did these six prominent Democratic senators, several of them leaders of their party, vote against hearing and cross-examining Jenkins?"

On 22nd November, 1963, a friend of Baker's, Don B. Reynolds told B. Everett Jordan and his Senate Rules Committee that Lyndon B. Johnson had demanded that he provided kickbacks in return for this business. This included a $585 Magnavox stereo. Reynolds also had to pay for $1,200 worth of advertising on KTBC, Johnson's television station in Austin. Reynolds had paperwork for this transaction including a delivery note that indicated the stereo had been sent to the home of Johnson.

Don B. Reynolds also told of seeing a suitcase full of money which Baker described as a "$100,000 payoff to Johnson for his role in securing the Fort Worth TFX contract". His testimony came to an end when news arrived that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated.

After declaring it was a whitewash he stormed out of the room.

As soon as Lyndon B. Johnson became president he contacted B. Everett Jordan to see if there was any chance of stopping this information being published. Jordan replied that he would do what he could but warned Johnson that some members of the committee wanted Reynold's testimony to be released to the public. On 6th December, 1963, Jordan spoke to Johnson on the telephone and said he was doing what he could to suppress the story because " it might spread (to) a place where we don't want it spread."

Abe Fortas, a lawyer who represented both Lyndon B. Johnson and Bobby Baker, worked behind the scenes in an effort to keep this information from the public. Johnson made threats against John Williams, Hugh Scott and Carl Curtis, who were all calling for Johnson to be fully investigated for corruption. Johnson also arranged for a smear campaign to be organized against Don B. Reynolds. To help him do this J. Edgar Hoover passed to Johnson the FBI file on Reynolds.

Lyndon B. Johnson also arranged for a smear campaign to be organized against Don B. Reynolds. To help him do this J. Edgar Hoover passed to Johnson the FBI file on Reynolds. Johnson then leaked this information to Drew Pearson and Jack Anderson. On 5th February, 1964, the Washington Post reported that Reynolds had lied about his academic success at West Point. The article also claimed that Reynolds had been a supporter of Joseph McCarthy and had accused business rivals of being secret members of the American Communist Party. It was also revealed that Reynolds had made anti-Semitic remarks while in Berlin in 1953.

A few weeks later the New York Times reported that Lyndon B. Johnson had used information from secret government documents to smear Don B. Reynolds. It also reported that Johnson's officials had been applying pressure on the editors of newspapers not to print information that had been disclosed by Reynolds in front of the Committee on Rules and Administration.

Don B. Reynolds also testified before the Rules Committee on 9th January, 1964. This time Reynolds provided little damaging evidence against Johnson. As Reynolds told John Williams after the assassination: "My God! There's a difference between testifying against a President of the United States and a Vice President. If I had known he was President, I might not have gone through with it." Maybe there were other reasons for this change of approach.

Reynolds also appeared before the Committee on Rules and Administration on 1st December, 1964. Before the hearing Reynolds supplied a statement implicating Bobby Baker and Matthew H. McCloskey (Treasurer of the National Democratic Party at the time) in financial corruption. However, the Democrats had a 6-3 majority on the Committee and Reynolds was not allowed to fully express the role that Lyndon B. Johnson had played in this deal.

Despite the efforts of his lawyer, Edward Bennett Williams, in 1967 Bobby Baker was found guilty of seven counts of theft, fraud and income tax evasions. This included accepting large sums in "campaign donations" intended to buy influence with various senators, but had kept the money for himself. He was sentenced to three years in federal prison but served only sixteen months.

Williams announced in 1969 he would not seek a fifth term in the Senate. He was replaced by his protégé, William V. Roth.

John Williams died on 11th January, 1988.

Primary Sources

(1) Bobby Baker, Wheeling and Dealing: Confessions of a Capitol Hill Operator (1978)

It was a story in the September issue of Vend magazine, a trade journal for the vending machine industry, that blew the lid off. The story told of my investment in Serv-U with lobbyist Fred Black, said that we'd gained many contracts while still a paper company, that we'd replaced many experienced vending companies where government contracts were the primary source of income, that we'd received liberal and instant credit from an Oklahoma bank controlled by Senator Kerr and his family, and cited Serv-U's spectacular growth. Suddenly, journalists came running in a pack. I went running to Abe Fortas and hired him to be my attorney.

Mike Mansfield sent for me; I gave him a report on the Ralph Hill Melpar situation and filled him in on how Serv-U had come about. Then I said, "If you think this will embarrass you personally, or embarrass the Senate or the Democratic party, I'm prepared to resign. I don't want to, because some might take it as an admission of guilt, but I'll do it if you think it's best." Mansfield quietly said that I was doing an excellent job for him, he had faith in me, and he wouldn't think of asking me to quit before I'd had my day in court. He issued a statement to the New York Times saying much the same.

The spate of newspaper stories set off a Pavlovian reaction in Senator John J. Williams, the Delaware Republican who liked to be labeled the "Watchdog of the Senate"; he had made a reputation by exposing the "mink coat and deep freeze" scandals involving General Harry Vaughan in the Truman administration and had contributed to the downfall of Sherman Adams, President Eisenhower's top White House assistant, when it developed that financer Bernard Goldfine had paid for vacation trips for Adams and gifted him with expensive furs. Senator Williams virtually declared open season on me, asking people who knew of my operations to come forward. One who did was my former partner in the Carousel, Geraldine Novak, whom my Serv-U Corporation had bought out with two promissory notes, the second of which was to be paid from future profits of the Carousel. Don Reynolds, the insurance man, came forward with his story of the hi-fi gift to LBJ and the advertising he had to buy on Johnson's TV and radio stations as a condition of writing a life insurance policy on him. Senator Williams was happy to announce such stories to the press.

He also presumably enjoyed breaking the story of how I'd bought the $28,000 town house Carole Tyler lived in. Lurid newspaper accounts spoke of "$7,500 worth of French wallpaper, wall-to-wall lavender carpets, and all-night parties of Washington's powerful and mighty." A great deal of hyperbole was involved. It was a nice enough house, but the furnishings were vastly inflated as to worth and style, as were the reports which sounded as if orgies occurred there with the setting of the sun.

There was an embarrassment involved, however. I had incorrectly and improperly listed Carole Tyler as my cousin when I applied for the loan, in order to satisfy the Federal Housing Authority's regulation that anyone buying an FHA-underwritten home must either live in it or have a relative living in it. At the time I gave the matter little more serious thought than would a groundhog; indeed, Carole and I had shared a laugh about it. "Well," I said to my lover, "at least you're my kissin' cousin. So it's only a little white lie."

(2) Mason City Globe-Gazette (1st October, 1964)

The Senate's reopened Bobby Baker investigation got off to a low keyed start Thursday, with testimony about an alleged 35,000 political payoff on the District of Columbia stadium contract.

The first witness called by the Senate rules committee was James A. Blaser, director of building and grounds for the District government and contracting officer for the 50,000 seat stadium. He told about the selection of architectural and engineering firms to draw plans for the stadium and testified that the opening of sealed bids on June 10, 1960, showed McCloskey & Co. of Philadelphia had submitted a low bid of $14,247,187.50.

Blaser said bid, submitted by 10 firms were kept in a padlocked box until they were opened at a public gathering in the office of the District Armory Board, which had responsibilityfor the stadium construction.

Sen. John J. Williams, R-Del., charged in a. senate speech a month ago that Matthew McCloskey, head of the Philadeliphia firm that won the contract made a $35,000 overpayment on the performance bond for the stadium to Don B. Reynolds, a local insurance agent.

Williams quoted Reynolds as telling him that $25,000 of this was funneled through Baker, then secretary to the Senate's Democratic majority, into the into the 1960 Kennedy-Johnson campaign fund. Baker resigned his $19,600 a year senate job last fall after questions were raised about his outside dealings and business interests.

McCloskey, former ambassador to Ireland, has been a Democratic fund raiser. At the outset of Thursday's hearing, Chairman B. Everett Jordan, D-N.C., said he wanted to explain, why the committee was taking testimony first about the details of the stadium project rather than plunging directly into Williams' payoff charge.

He said that Williams had implied that there was something very seriously wrong in the whole conduct of the stadium project, that McCloskey had "possibly showed favoritism" and that changes in plans after, the construction award might have given McCloskey a "price advantage" These changes ran the cost up by several million dollars

(3) Seymour Hersh, The Dark Side of Camelot (1997)

In September newspapers and magazines began unraveling a seamy story of Baker's financial ties to a fast-growing vending machine company. Baker and a group of investors, it turned out, had been awarded many contracts while the new company was still being organized, and had also received instant credit from a bank controlled by Democratic senator Robert Kerr, of Oklahoma, and his family. By October the Baker scandal had turned into a newspaper tempest, and reporters were beginning to dig up dirt on a number of present and past senators - including Baker's mentor, Vice President Johnson. A Maryland insurance broker named Donald Reynolds met privately with Senator John Williams of Delaware, a Republican, and complained to him about advertising he had been forced to buy on the vice president's radio and television stations in Austin, Texas, as a condition of writing Johnson's life insurance policy. Johnson also demanded, and got, a television set and a new stereo from Reynolds as a cost of doing business. John Williams's best friend in the Senate was Carl Curtis of Nebraska, the senior Republican on the Rules Committee. As the scandal spread in the newspapers, alarming other Democrats - including senators who had received many thousands of dollars in campaign contributions through Baker - the Rules Committee announced an all-out investigation. Baker's personal life was soon thrust into the limelight, along with the mysterious goings-on at the Quorum Club. It took only days for the Republicans on the committee to find out all they needed to know about Ellen Rometsch.