Raphael Samuel

Raphael Samuel, the son of Jewish parents, was born in London in 1934. He spent his boyhood a wartime evacuee in Buckinghamshire and then in Hampstead Garden Suburb, where he went to the progressive King's Alfred's School. After his parents were divorced (his father was a solicitor), Raphael was brought up by his mother Minna Keal, a gifted composer, with close links to his uncle, the historian Chimen Abramsky. (1)

His mother was an active member of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Samuel joined as a young man and later recalled: "Like many Communists of my time, I combined a powerful sense of apartness with a craving for recognition, alternating gestures of defiance with a desire to be ordinary and accepted as one of the crowd. If one wanted to be charitable, one might say that it was the irresolvable duality on which British Communists find themselves impaled today." (2)

This view was criticised by his friend, John Saville in his book, Memoirs from the Left (2003): "I do not deny the validity of Raphael Samuel's own personal history, especially in his younger days... The historian in him, however, might have acknowledged that it was a very unusual story, typical of some, perhaps many, Jewish comrades but not in any way relevant to the working-class militants who were joining the Communist Party at the time that Raphael was growing up in the 1940s." (3)

Communist Party Historians' Group

Samuel went to Balliol College, Oxford, where he was taught by Christopher Hill, an authority on 17th century revolutionary traditions and another Marxist. He gained a first and began teaching at Ruskin College. (4) Samuel also joined forces with Hill, E. P. Thompson, Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, A. L. Morton, John Saville, George Rudé, Rodney Hilton, Dorothy Thompson, Edmund Dell, Victor Kiernan and Maurice Dobb to form the Communist Party Historians' Group. (5)

Saville later recalled: "The Historian's Group had a considerable long-term influence upon most of its members. It was an interesting moment in time, this coming together of such a lively assembly of young intellectuals, and their influence upon the analysis of certain periods and subjects of British history was to be far-reaching. For me, it was a privilege I have always recognised and appreciated." (6)

In 1952 members of the group founded the journal, Past and Present. Over the next few years the journal pioneered the study of working-class history and is "now widely regarded as one of the most important historical journals published in Britain today." (7) As Christos Efstathiou has explained: "Most of the members of the Group had common aspirations as well as common past experiences. The majority of them grew up in the inter-war period and were Oxbridge undergraduates who felt that the path to socialism was the solution to militarism and fascism. It was this common cause that united them as a team of young revolutionaries, who saw themselves as the heir of old radicalism." (8)

Hungarian Uprising

During the 20th Party Congress in February, 1956, Nikita Khrushchev launched an attack on the rule of Joseph Stalin. He condemned the Great Purge and accused Joseph Stalin of abusing his power. He announced a change in policy and gave orders for the Soviet Union's political prisoners to be released. Pollitt found it difficult to accept these criticisms of Stalin and said of a portrait of his hero that hung in his living room: "He's staying there as long as I'm alive". Khrushchev's de-Stalinzation policy encouraged people living in Eastern Europe to believe that he was willing to give them more independence from the Soviet Union. (9)

In Hungary the prime minister Imre Nagy removed state control of the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. Nagy also released anti-communists from prison and talked about holding free elections and withdrawing Hungary from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev became increasingly concerned about these developments and on 4th November 1956 he sent the Red Army into Hungary. During the Hungarian Uprising an estimated 20,000 people were killed. Nagy was arrested and replaced by the Soviet loyalist, Janos Kadar. (10)

Raphael Samuel, like most members of the Communist Party Historians' Group, supported Imre Nagy and as a result, like most Marxists, he left the Communist Party of Great Britain after the Hungarian Uprising and a "New Left movement seemed to emerge, united under the banners of socialist humanism... the New Leftists aimed to renew this spirit by trying to organise a new democratic-leftist coalition, which in their minds would both counter the 'bipolar system' of the cold war and preserve the best cultural legacies of the British people." (11)

As John Saville pointed out: "I still regard it as wonderfully fortunate that I was of the generation that established the Communist Historians' group. For ten years we exchanged ideas and developed our Marxism into what we hoped were creative channels. It was not chance that when the secret speech of Khrushchev was made known in the West, it was members of the historians' group who were among the most active of the Party intellectuals on demanding a full discussion and uninhibited debate." (12)

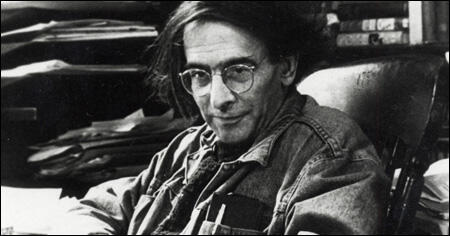

Samuel became a tutor at Ruskin College in 1962. He was an outstanding teacher. One student recalled: "I came to Ruskin knowing I could not write an essay, and left Ruskin sure that I could write a book".John Prescott was one of his mature students: "He would turn up with his hair all over the place, in a style of dressing that was all his own... He arrived with bags full of poems and bits of papers and references and he would pull one out when he wanted to make a point. He made me do something I thought I'd never do. Not just write an essay - that was difficult enough for me - but use the experience of poetry to illustrate a point. Until then I had thought poetry was about them and not us." (13)

History Workshop Movement

In 1967 Samuel created the History Workshop Movement. Samuel borrowed the name from one of his heroines, Joan Littlewood, founder of Theatre Workshop. (14) As Mervyn Jones has pointed out, Samuel was dedicated "to a special kind of history; rooted in left-wing politics, and aiming to rediscover the lives of the millions overlooked by historians of big names and big events." (15)

Other important figures in the History Workshop movement included Anna Davin, Alun Howkins and Sally Alexander. The workshops that were held every year attracted up to a thousand participants. While the themes explored varied widely, the events were primarily a showcase for history seen from a non-elite perspective, "people's history" as it was labelled. In the early years this meant primarily working-class history (16)

History Workshop Conference of November 1968 played a central organising role in developing what became known as women's history. Keith Flett has argued that the History Workshop was an attempt to actively recover the history of ordinary people and their movements. "In many ways this was a step forward from the sometimes rather rigid orthodoxies of more mechanical Marxist histories." (17)

Raphael Samuel Published Work

Books published by Samuel include Village Life and Labour (1975), Miners, Quarrymen and Saltworkers (1977), People's History and Socialist Theory (1981),East End Underworld (1981), Culture, Ideology and Politics (1983), Theatres of the Left: 1880-1935 (1985), The Lost World of Communism (1986), The Enemy Within: The Miners' Strike of 1984 (1987), Patriotism: The Making and Unmaking of British National Identity (1989), Patriotsm: Minorities and Outsiders (1989), The Myths We Live By (1990), Theatres of Memory (1996) and Island Stories: Unravelling Britain (1997).

In 1995 Samuel created the Raphael Samuel History Centre in East London University. The historian, Gareth Stedman-Jones, has argued: "The extent of his empathy was exceptional. No one charted more exactly the ways in which the Industrial Revolution had increased the extent of toil in every branch of Victorian industry... His insights were the product of an omnivorous intellectual appetite, which crossed disciplines and periods: Samuel wrote with the insights of a literary critic, the acuity of an anthropologist and the wit of a political journalist. Up until his last hours he remained passionately engaged with the future of history, both of his own many projects and those of the many friends and admirers whom he had helped to inspire."(18)

Raphael Samuel died of cancer on 9th December 1996.

Primary Sources

(1) Raphael Samuel, New Left Review (1985)

Like many Communists of my time, I combined a powerful sense of apartness with a craving for recognition, alternating gestures of defiance with a desire to be ordinary and accepted as one of the crowd. If one wanted to be charitable, one might say that it was the irresolvable duality on which British Communists find themselves impaled today.

(2) Barbara Taylor, History of History Workshop (22nd November 2012)

History Workshop was a popular movement for the democratisation of History which flourished in Britain from the late 1960s to the mid 1980s (with sporadic activity continuing into the 1990s). It emerged from Ruskin College Oxford where Raphael Samuel, the movement’s initiator and presiding spirit, taught history for many decades. In the course of the 1970s History Workshop spread across Britain, spawning dozens of regional and local initiatives, publishing many books, pamphlets and journals (including the still-extant History Workshop Journal), and acquiring influence throughout intellectual and educational circles. During these years the movement also went international, spawning sister workshops in Germany, France, Italy, South Africa and America. Its high point was reached in the late 1970s, and thereafter it went into a slow decline, although many of the developments it helped to foster (such as oral history and women’s history) continue to flourish today.

(3) Carolyn Steedman, Radical Philosophy (March, 1997)

Raphael Samuel's lasting memorials will be the work he inspired in the generations of students he taught at Ruskin College, Oxford, from 1962 to 1996, and History Workshop, in its protean forms of annual conferences, local networks and federations - which spread across Europe and Scandinavia - and its eponymous journal. A loose coalition of worker-historians and full-time socialist researchers was what he called it...

The standard charge against the history Samuel inspired was of a fanatical empiricism and a romantic merging of historians and their subjects in crowded narratives, in which each hard-won detail of working lives, wrenched from the cold indifference of posterity, is piled upon another, in a relentless rescue of the past. When he was himself subject to these charges, it was presumably his fine and immensely detailed accounts of the labour process that critics had in mind. But it was meaning rather than minutiae that he cared about. If, as Gareth Stedman-Jones suggested in his Independent obituary, Raphael Samuel charted better than anyone else the desperate increase of hard labour in every branch of industry and manufacture brought about by Victorian industrial capitalism (on the land as much as in the factory), then it was because the details inscribed the meaning of that toil, those lives, to those who lived them.

(4) Gareth Stedman-Jones, The Independent (March, 1997)

Raphael Samuel brought to the writing and popularisation of history a seemingly inexhaustible energy and creativity. He was also an inspired teacher and the author of books and essays, which have expanded beyond recognition the intellectual and imaginative ranges both of English history and of the writing of history itself.

But he was not only a teacher and a writer; he was also an organiser and a prophet, a close, and sometimes uncanny reader of "the signs of the times". He preached and practised a new vision of popular history: a democratic history which put the everyday lives of ordinary people at the heart of a large and even sweeping history of the nations of Britain over the last two centuries.

Samuel gave new meaning to the idea of history as an experimental art, inventing the History Workshop (a term he borrowed from one of his heroines, Joan Littlewood, founder of Theatre Workshop) first as a local and then as an international movement. The extent of his empathy was exceptional. No one charted more exactly the ways in which the Industrial Revolution had increased the extent of toil in every branch of Victorian industry, but no one could have acknowledged more generously the contribution of Tory antiquaries in Early Hanoverian England to the writing of national history. His cast of historical actors ranged from Catholic priests ministering among the post-famine Irish poor, the proletarian Gladstonian roughs of Headington Quarry through South Wales village Bolsheviks in the 1920, to the mobsters of the Edwardian East End underworld.

His insights were the product of an omnivorous intellectual appetite, which crossed disciplines and periods: Samuel wrote with the insights of a literary critic, the acuity of an anthropologist and the wit of a political journalist. Up until his last hours he remained passionately engaged with the future of history, both of his own many projects and those of the many friends and admirers whom he had helped to inspire.

(5) John Prescott, The Guardian (11th December, 1996)

Raphael Samuel opened my mind when I was a student in the 1960s. Until I went to Ruskin and met him, my education had come from correspondence courses, which I used to complete in a 14-bunk cabin after 20 hours' duty as a seaman on a liner. To move from that to two of you in a college room with a tutor was an experience, but Raph was never my image of a tutor.

He would turn up with his hair all over the place, in a style of dressing that was all his own and that was brilliant captured in the photograph of him which the Guardian published yesterday. He arrived with bags full of poems and bits of papers and references and he would pull one out when he wanted to make a point.

He made me do something I thought I'd never do. Not just write an essay - that was difficult enough for me - but use the experience of poetry to illustrate a point. Until then I had thought poetry was about them and not us.

He had this tremendous understanding of the inner inferiority that mature students have in a society that tells them they've missed out. He not only understood what was inside the student, he unlocked it and channelled it into written and verbal debate. There wasn't an ounce of superiority in him. In those tutorials he was often as much the student as the lecturer. He learned from you and you learned from him. He was fascinated by other people's experience.

I remember once that I did a mock exam while I was at Ruskin. I had a terrible time. I was so frustrated that I couldn't say what I wanted that I stormed out. Raph chased me down Walton Street, but he couldn't catch me. When I got back there was a note on my desk in that big hand writing of his telling me not to worry and to come and have a talk and a cup of coffee. He was always supportive like that.

(6) Mervyn Jones, The Times (11th December 1996)

After the death of E.P.Thompson in 1993, that of Raphael Samuel is the gravest loss to the profession of history - but to a special kind of history; rooted in left-wing politics, and aiming to rediscover the lives of the millions overlooked by historians of big names and big events.

Thompson and Samuel had much in common. Both learnt their trade in adult education, not in the universities. Both left the Communist party in 1956 to devote themselves to the New Left, which sought to free the spirit of socialism from the dark record of Stalinism and also from the pragmatism of social democracy. in a speech in 1988, at a conference (or reunion) of "The New Left 30 Years On", Samuel recalled: "We were all forward-looking and iconoclastic, breaking with age-old shibboleths".

He came from a Jewish family with roots in the East End of London, and spent his boyhood a wartime evacuee in Buckinghamshire and then in Hampstead Garden Suburb, where he went to the progressive King Alfred's School. After his parents were divorced (his father was a solicitor), Raphael was brought up by his mother Minna Keal, a gifted composer, with close links to his uncle, the historian Chimen Abramsky. Minria Keal. Abramsky and Abramsky's wife were active and dedicated communists and the boy was initiated into the faith - though that word is unjust to the intellectual sophistication of scholarly Marxism.

Samuel was born to be an historian and was already in a Communist historians' discussion group as a precocious schoolboy. He had the vital quality of living at the same time in the past, the present and the future.

Everything interested him, from public health to colonial rebellion and from street lighting to street fighting. Up to the end of his life he would argue as fervently about the tactics of the Chartists as about the destruction of the Labour Party (as he saw it) by Tony Blair.

At Balliol College, Oxford, Samuel's tutor was Christopher Hill, an authority on 17th century revolutionary traditions and another Marxist (also to leave the CP in 1956). He gained a first and began teaching at Ruskin College. He was the founder, with Stuart Hall and others, of Universities and Left Review, a journal born of the political turmoil caused by the simultaneous crises of Hungary and Suez. It sponsored a crowded, excited meeting in London addressed by yet another Marxist scholar, Isaac Deutscher.

Thompson had founded the New Reasoner and were was no room for two similar journals, so they merged in 1960 as The New Left Review edited by Hall. The New Left was now a movement, with hundreds of activists who trod the road to Aldermaston and waved banners at demonstrations on all kinds of issues. Samuel was once arrested and, rather than save his time by pleading guilty and paying the fine, went to court to debate the right to remonstrate with the magistrate. He was fined anyway.

Inevitably, the atmosphere of the movement was, in a then popular phrase, one of creative chaos. A Soho coffee house, called The Partisan, was started not just as a rendezvous but as an enterprise, which, it was confidently believed, would finance the movement and the journal. in the 1950s it was difficult to lose money with a coffee house, but the New Left managed it.

Meanwhile, Samuel was rushing between London and Oxford, loyal to Ruskin, where he went on teaching until the year of his death, despite opportunities to move to more prestigious jobs.

(7) Keith Flett, Socialist Review (January, 1997)

Raphael Samuel was one of the most prominent historians in the country to support history from below the attempt to actively recover the history of ordinary people and their movements. In many ways this was a step forward from the sometimes rather rigid orthodoxies of more mechanical Marxist histories. It fed in directly, too, to the resurgence of socialist ideas after 1968 and to the birth of the women's movement in which the History Workshop Conference of November 1968 played a central organising role.

Samuel could be fiercely critical of socialists with whom he disagreed. Debate has raged, for example, about whether a series of articles he wrote about the Communist Party in the 1940s and 1950s in New Left Review under the title "The Lost World of British Communism" was an attempt to write an affectionate history from below of what it had been like to be a CP member before 1956 or an attack on any kind of left wing political activism.

(8) Emma Griffin, History Today (2 February 2015)

When history emerged as a scholarly discipline in British universities at the end of the 19th century, it rarely took working-class people as its focus. History was about the great and the good – about kings, queens, archbishops and diplomats. Historians studied reigns, constitutions, parliaments, wars and religion. Although some historians inevitably strayed from the mainstream, they rarely organised their ideas around the concept of ‘the working class’. For example, Ivy Pinchbeck’s Women Workers and the Industrial Revolution, 1750-1850 (1930) and, with Margaret Hewitt, Children in English Society (1969) certainly foreshadowed the concerns of a later generation of social historians, yet took ‘women’ and ‘children’, rather than the ‘working class’ as their subject.

This changed with the emergence of the social history movement in the second half of the 20th century. At the end of the Second World War and – a decade or so later – as the universities expanded, the historian’s remit widened enormously. Poor and disenfranchised subjects, such as the working women and orph-aned children that Pinchbeck had studied, swiftly moved from the intellectual margins to the mainstream. The newly-formed social history movement splint-ered into numerous branches – black history, subaltern studies, women’s history, urban history, rural history and so on. Soon working-class history had also emerged as a distinct historical specialism. The Communist Party History Group (founded 1946) and the Society for the Study of Labour History (1960) together consolidated its place in the universities. The History Workshop movement, established in the late 1960s with a slightly broader remit, provided an important platform for the study of ordinary people. Now historians of the working class enjoyed all the trappings of a modern academic sub-discipline, with their own societies, annual conferences and journals.

The cause of this fledgling historical strand was greatly advanced through association with some of the leading scholars of the age, including the Communist Party History Group members Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm, Raphael Samuel and E. P. Thompson. These four were also part of the group that founded the journal Past & Present, now widely regarded as one of the most important historical journals published in Britain today. Thompson’s monumental The Making of the English Working Class (1963) was arguably the single most significant contribution to working-class history, but it is easy to forget that he was just one part of a larger community of scholars with a shared interest in the emergence and experiences of the working class at the time of the British Industrial Revolution.