Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany

On 27th February, 1933, someone set fire to the Reichstag. Several people were arrested including a leading, Georgi Dimitrov, general secretary of the Comintern, the international communist organization. Dimitrov was eventually acquitted but a young man from the Netherlands, Marianus van der Lubbe, was eventually executed for the crime. As a teenager Lubbe had been a communist and Hermann Goering used this information to claim that the Reichstag Fire was part of a KPD plot to overthrow the government.

Adolf Hitler gave orders that all leaders of the German Communist Party (KPD) should "be hanged that very night." Paul von Hindenburg vetoed this decision but did agree that Hitler should take "dictatorial powers". KPD candidates in the election were arrested and Goering announced that the Nazi Party planned "to exterminate" German communists. Thousands of members of the Social Democrat Party and KPD were arrested and sent to Germany's first concentration camp at Dachau, a village a few miles from Munich. The head of the Schutzstaffel (SS), Heinrich Himmler was placed in charge of the operation, whereas Theodor Eicke became commandant of the first camp and was staffed by members of the SS Death's Head units.

Originally called re-education centres the Schutzstaffel (SS) soon began describing them as concentration camps. They were called this because they were "concentrating" the enemy into a restricted area. Hitler argued that the camps were modeled on those used by the British during the Boer War. According to Andrew Mollo, the author of To The Death's Head: The Story of the SS (1982): "Theodor Eicke, a rough unstable character whose violent and unruly behaviour had already given Himmler many headaches. At last Himmler found an ideal backwater for his troublesome subordinate and sent him off to Dachau."

Theodor Eicke later recalled: "There were times when we has no coats, no boots, no socks. Without so much as a murmur, our men wore their own clothes on duty. We were generally regarded as a necessary evil that only cost money; little men of no consequence standing guard behind barbed wire. The pay of my officers and men, meagre though it was, I had to beg from the various State Finance Offices. As Oberführer I earned in Dachau 230 Reichmark per month and was fortunate because I enjoyed the confidence of my Reichsführer (Himmler). At the beginning there was not a single cartridge, not a single rifle, let alone machine guns. Only three of my men knew how to operate a machine gun. They slept in draughty factory halls. Everywhere there was poverty and want. At the time these men belonged to SS District South. They left it to me to take care of my men's troubles but, unasked, sent men they wanted to be rid of in Munich for some reason or another. These misfits polluted my unit and troubled its state of mind. I had to contend with disloyalty, embezzlement and corruption."

With the support of Heinrich Himmler things began to improve: "From now on progress was unimpeded. I set to work unreservedly and joyfully; I trained soldiers as non-commissioned officers, and non-commissioned officers as leaders. United in our readiness for sacrifice and suffering and in cordial comradeship we created in a few weeks an excellent discipline which produced an outstanding esprit de corps. We did not become megalomaniacs, because we were all poor. Behind the barbed-wire fence we quietly did our duty, and without pity cast out from our ranks anyone who showed the least sign of disloyalty. Thus moulded and thus trained, the camp guard unit grew in the quietness of the concentration camp.

Wolf Sendele, a member of the SS thought that these camps were only for political prisoners like Ernest Thalmann and other members of the German Communist Party (KPD): "We knew well enough that these camps existed, detention camps, or whatever they were called, and that political opponents were being incarcerated. We were never quite clear why. God knows, the crimes themselves were not serious enough to remove a man from his house and home. But you thought to yourself - it's just a temporary measure, they'll put them away in a camp for three or four weeks, and then let them go again, when they've established that they're just harmless fellows - not like Thalmann (leader of the German Communist Party - KPD) or people who were real agitators."

Hermann Langbein, the author of Against All Hope: Resistance in the Nazi Concentration Camps 1938-1945 (1992) has pointed out: "National Socialism replaced democratic institutions with a system of command and obedience, the so-called Fuhrer principle, and it was this system that the Nazis installed in their concentration camps. It goes without saying that any command by a member of the SS had to be unconditionally carried out by all prisoners. Refusal or hesitation was liable to lead to a cruel death. The camp administration not only saw to it that every command was carried out, but also held inmates assigned to certain jobs responsible for completing them. In this way it facilitated its own work and was also able to play one prisoner off against another.... Each unit housing prisoners, whether a barrack or a brick building, was called a block. The camp administration held a senior block inmate (Blockdltester) responsible for enforcing discipline, keeping order, and carrying out all commands. If a dwelling unit was divided into rooms, a senior block inmate was assisted by senior barracks inmates and their staff. A senior camp inmate (Lageraltester) was responsible for the operation of the entire camp, and it was he who proposed the appointment of senior block inmates to the officer-in-charge."

Langbein, who was an inmate in Dachau, explained that each work group was headed by a capo (trusty). "The capo himself was exempted from work, but he had to see to it that the required work was done by his underlings. Capos, senior block inmates, and senior camp inmates were identified by an armband with the appropriate inscription. These armband wearers, as they were generally called, were under the protection of the camp administration, often enjoyed extensive privileges, and as a rule had unlimited power over those under them. This is to be taken literally, for if an armband wearer killed an underling, he did not (with a few exceptions) have to answer to anyone, provided a timely report of the death was made and the roll call was corrected. An ordinary prisoner was completely at the mercy of his capo and senior block inmate."

Heinrich Himmler argued that: "These approximately 40,000 German political and professional criminals... are my 'noncommissioned officer corps' for this whole kit and caboodle. We have appointed so-called capos here; one of these is the supervisor responsible for thirty, forty, or a hundred other prisoners. The moment he is made a capo, he no longer sleeps where they do. He is responsible for getting the work done, for making sure that there is no sabotage, that people are clean and the beds are of good construction.... So he has to spur his men on. The minute we're dissatisfied with him, he is no longer a capo and bunks with his men again. He knows that they will then kill him during the first night."

Inmates had to wear a coloured symbol to indicate their category. This included political prisoners (red), convicts (greens), Jews (yellow), homosexuals (pink), Jehovah's Witnesses (violet) and what the Nazis described as anti-socials (black). The anti-social group included gypsies and prostitutes. The Schutzstaffel (SS) preferred those with a criminal record to be capos. As Hermann Langbein has pointed out: "As a rule the SS bestowed armbands on prisoners they could expect to be willing tools in return for their privileged status. As soon as German convicts arrived in the camps the SS preferred them to morally stable men."

Harry Naujoks, a member of the German Communist Party (KPD), was an inmate at Sachsenhausen near Oranienburg. He later recalled what life was like in the camp: "Every SS guard had to be greeted by the prisoners. When a prisoner walked by an SS guard, six paces beforehand, the prisoner had to place his left hand on the seam of his trousers and with his right hand, quickly doff his cap and lay it on the seam of his trousers on the right-hand side. The prisoner had to walk by the guard while looking at him, as at attention. Three paces afterward, he was allowed to put his cap back on. This had to be done with the thumb pressed against the palm, the four fingers resting on the cap, pressed against the seam of the trousers. If this didn't happen quickly enough or the prisoner didn't snap to attention enough or his fingers weren't taut enough, or anything else happened that struck the SS guard as being insufficient, then one's ear was boxed, he had extra sports, or was reported."

Rudolf Hoess, one of the guards at Dachau, later recalled: "I can clearly remember the first flogging that I witnessed. Eicke had issued orders that a minimum of one company from the guard unit must attend the infliction of these corporal punishments. Two prisoners who had stolen cigarettes from the canteen were sentenced to twenty-five lashes each with the whip. The troops under arms were formed up in an open square in the centre of which stood the Whipping block.Two prisoners were led forward by their block leaders. Then the commandant arrived. The commander of the protective custody compound and the senior company commander reported to him. The Rapportfiihrer read out the sentence and the first prisoner, a small impenitent malingerer, was made to lie along; the length of the block. Two soldiers held his head and hands and two block leaders carried out the punishment, delivering alternate strokes. The prisoner uttered no sound. The other prisoner, a professional politician of strong physique, behaved quite differently. He cried out at the very first stroke and tried to break free. He went on screaming to the end, although the commandant yelled at him to keep quiet. I was standing in the first rank and was compelled to watch the whole procedure. I say compelled, because if I had been in the rear I would not have looked. When the man began to scream I went hot and cold all over. In fact the whole thing, even the beating of the first prisoner made me shudder. Later on, at the beginning of the war, I attended my first execution, but it did not affect me nearly so much as witnessing that first corporal punishment."

After the 1933 General Election Hitler passed an Enabling Bill that gave him dictatorial powers. His first move was to take over the trade unions. Its leaders were sent to concentration camps and the organization was put under the control of the Nazi Party. The trade union movement now became known as the Labour Front. Soon afterwards the Communist Party and the Social Democrat Party were banned. Party activists still in the country were arrested and by the end of 1933 over 150,000 political prisoners were in concentration camps. Hitler was aware that people have a great fear of the unknown, and if prisoners were released, they were warned that if they told anyone of their experiences they would be sent back to the camp.

It was not only left-wing politicians and trade union activists who were sent to concentration camps. The Gestapo also began arresting beggars, prostitutes, homosexuals, alcoholics and anyone who was incapable of working. Although some inmates were tortured, the only people killed during this period were prisoners who tried to escape and those classed as "incurably insane". Inmates wore serial numbers and coloured patches to identify their categories: red for political prisoners, blue for those who were foreigners, violet for religious fundamentalists, green for criminals, black for those considered to be anti-social and pink for homosexuals.

In May 1934 Theodor Eicke was given responsibility of reorganizing Germany's concentration camp system. One of his recommendations was that guards should be warned that they would be punished if they showed prisoners any signs of humanity. Charles W. Sydnor, the author of Soldiers of Destruction (1977) believed that "Eicke's personality, in particular his unremitting hatred for everything and everyone non-Nazi, influenced definitively the development, the structure, and the uniquely inhumane ethos of the concentration camps. Eicke was convinced that the camps were the most effective instrument available for destroying the enemies of National Socialism. He regarded all prisoners as subhuman adversaries of the State, marked for immediate destruction if they offered the slightest resistance. Eicke eventually succeeded in nurturing this same attitude among many SS guards in the camps.... Like many of the concentration camp commanders he trained, Eicke basically was pitiless and cruelly insensitive to human suffering, and regarded qualities such as mercy and charity as useless, outmoded absurdities that could not be tolerated in the SS."

Eicke's biographer, Louis L. Snyder, has argued: "Eicke's influence on the organization and spirit of the SS guard formations was second only to that of Himmler. his regulations included precise instructions on solitary confinement, corporal punishment, beatings, reprimands, and warnings. he informed his guards that any pity for enemies of the state was was unworthy of SS men. It is claimed that Eicke said that any man with a soft heart would do well to "retire quickly to a monastery."

Hermann Langbein arrived in Dachau on 1st May 1941. He later wrote in Against All Hope (1992): "On May 1, 1941, I arrived in Dachau together with many other Austrian veterans of the Spanish Civil War. For over two years, we had been interned in camps in southern France, and only internees who live together day and night can get to know one another as well as we did... The general expressions of support from the old political prisoners that greeted us, the first large group of veterans of the Spanish Civil War to arrive in Dachau, did us good morally and in some instances helped us concretely as well."

Langbein was shocked by conditions in the camp. "We had to march out at dawn onto the parade ground for early morning roll call. It was always a dreadful military ceremony. Everyone had to stand bolt upright in rows. The order hats off had to be done with total precision. If there was some mistake or other, then there were punishment exercises. Then the SS took the roll call - to check whether the numbers tallied. That was always the most important thing in every concentration camp - the numbers had to be right at every roll call. No one was allowed to be absent. It made no difference if someone had died during the night - the body would be laid out and included in the roll. And then, when roll call was over, we had to form up into our working parties. And every working party had its own assembly area, which one had to know in order to line up. And then the parties set off for work - depending on whether one was working inside the camp or outside. The outside parties were escorted by SS men. The working day was determined by the time of year. Work was determined by hours of daylight, not the clock. The parties could only leave camp when it was already half-light, so that people couldn't escape under cover of darkness."

Langbein was able to survive the experience by gaining a job in the camp hospital: "A German Communist who had been interned for many years - presented me to his SS boss, who had a request for a clerk from the prison hospital... The Work Assignments man told him that no other inmates were available who had the proper qualifications - the ability to spell correctly, use a typewriter, and take shorthand. He had prepared me in advance to answer the SS questions in such a way that I made a positive impression. With surprising speed, I was placed on a detail with exceptionally good working conditions. Because we also slept in the infirmary, we were not subject to the harassing checks in the blocks. We did not need to show up for the morning and evening roll calls, and we had a roof over our heads as we did our physically undemanding work."

In June, 1941, Heinrich Himmler ordered that Auschwitz be greatly increased in size and the following year it became an extermination camp. Bathhouses disguised as gas chambers were added. Hoess introduced Zyklon-B gas, that enabled the Nazis to kill 2,000 people at a time. Hess was promoted to Deputy Inspector General and took charge of the Schutzstaffel (SS) department that administered German concentration camps. In a SS report Hoess was described as "a true pioneer in this area because of his new ideas and educational methods."

At the Wannsee Conference held in January 1942 it was decided to make the extermination of the Jews a systematically organized operation. After this date extermination camps were established in the east that had the capacity to kill large numbers including Belzec (15,000 a day), Sobibor (20,000), Treblinka (25,000) and Majdanek (25,000).

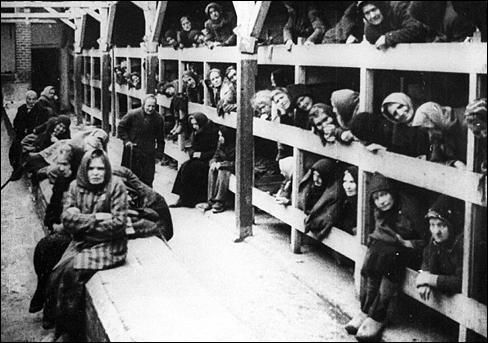

In January 1942, Rebecca Weisner was sent to a women's camp near Breslau in eastern Germany. "When you got to the camp they took away whatever we had - our watches, clothes, and everything. They shaved our hair. It was tragic. You know, you're a young girl and they shave your head. We didn't get any food anymore. If you asked me what was the worst in the camp for me personally, it was hunger. It was also cold; we didn't have much warmth. We slept in an old factory hall, in bunk beds, up and down in wooden bunks and straw. It was like an outdoor, not an indoor, house, with little holes in the middle."

Later that year, Rebecca Weisner's brother, parents, grandparents and cousins were all taken to Auschwitz, an extermination camp. Over 250,000 people who had been living in Poland died in the camp. It is estimated that as many as 4 million people died in gas ovens and by a variety of other methods at Auschwitz. "Somehow we knew those things were more or less going on that there was Auschwitz and that they had gas ovens to gas all the people, children and so. We knew that... You know, they were young - my mother was forty; my father was forty-four; my brother was just barely twenty - and this was something that I had to live with... I cried for maybe two days because I knew that I was all alone. I only had one brother and I really didn't want to live at that point. I never cried again after that time. Until today, I still cannot cry and I have had a lot of emotional problems because of all those things. I can't cry; I choke, but I can't cry."

Rudolf Hoess later admitted: "I must admit that the gassing process had a calming effect on me. I always had a horror of the shootings, thinking of the number of people, the women and children. I was relieved that we were spared these blood baths.... We tried to fool the victims into believing that they were going through a delousing process. Of course, at times they realized our true intentions and we sometimes had riots and difficulties. Frequently women would hide their children under their clothes, but we found them and we sent the children to be exterminated. We were required to carry out these exterminations in secrecy, but the foul and nauseating stench from the continued burning of bodies permeated the whole area and all the people living around Auschwitz knew what was going on."

Gisella Perl was allowed to live because she was employed as a doctor at Auschwitz. One of the tasks that Gisella had to carry out was to persuade inmates to give blood: "The doctors of the hospital were sent for. The sight which greeted us when we entered Block VII is one never to be forgotten. From the cages along the walls about six hundred panic-stricken, trembling young women were looking at us with silent pleading in their eyes. The other hundred were lying on the ground, pale, faint, bleeding. Their pulse was almost inaudible, their breathing strained and deep rivers of blood were flowing around their bodies. Big, strong SS men were going from one to the other sticking tremendous needles into their veins and robbing their undernourished, emaciated bodies of their last drop of blood. The German army needed blood plasma! The guinea pigs of Auschwitz were just the people to furnish that plasma. Rassenschande or contamination with 'inferior Jewish blood' was forgotten. We were too 'inferior' to live, but not too inferior to keep the German army alive with our blood. Besides, nobody would know. The blood donors, along with the other prisoners of Auschwitz would never live to tell their tale. By the end of the war fat wheat would grow out of their ashes and the soap made of their bodies would be used to wash the laundry of the returning German heroes."

In February 1942, Oswald Pohl, chief of the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office (SS-Wirtschafts-Verwaltungs Hauptamt), took control of the administration of the concentration camps. Pohl clashed with Theodor Eicke over the way the camps should be run. According to Andrew Mollo, the author of To The Death's Head: The Story of the SS (1982): "Pohl insisted on better treatment for camp inmates, and SS men were forbidden to strike, kick or even touch a prisoner. Inmates were to be better housed and fed, and even encouraged to take an interest in their work. Those who did were to be trained and rewarded with their freedom. There was a small reduction in the number of cases of maltreatment, but food and accommodation were still appalling, and in return for these 'improvements' prisoners were still expected to work eleven hours per day, six or seven days a week."

Pohl came under pressure from Albert Speer to increase production at the camps. Pohl complained to Heinrich Himmler: "Reichsminister Speer appears not to know that we have 160,000 inmates at present and are fighting continually against epidemics and a high death-rate because of the billeting of the prisoners and the sanitary arrangements are totally inadequate." In a letter written on 15th December, 1942, Himmler suggested an improvement in the prisoner's diet: "Try to obtain for the nourishment of the prisoners in 1943 the greatest quantity of raw vegetables and onions. In the vegetable season issue carrots, kohlrabi, white turnips and whatever such vegetables there are in large quantity and store up sufficient for the prisoners in the winter so that they had a sufficient quantity every day. I believe we will raise the state of health substantially thereby."

Harry Naujoks, was senior camp inmate (Lageraltester) of Sachsenhausen. In May 1942, Naujoks was ordered by Lagerführer Fritz Suhren to execute a fellow prisoner. He refused and was forced to stand next to the gallows during the hanging, which was made to be particularly slow and painful. Naujoks was discovered to be part of a camp resistance group and in November 1942, he and 17 other political prisoners were deported to Flossenbürg, a concentration camp under the control of the Greens. However, his earlier fairness was rewarded as Naujoks was told by one Green "In Sachsenhausen you treated as like comrades, and you can be sure that we shall treat you the same way here."

Gisella Perl later provided information on the activities of Dr. Josef Mengele in Auschwitz. Nadine Brozan has argued: "As one of five doctors and four nurses chosen by Dr. Mengele to operate a hospital ward that had no beds, no bandages, no drugs and no instruments, she tended to every disease wrought by torture, starvation, filth, lice and rats, to every bone broken or head cracked open by beating. She performed surgery, without anesthesia, on women whose breasts had been lacerated by whips and become infected." Gisella admitted: ''I treated patients with my voice, telling them beautiful stories, telling them that one day we would have birthdays again, that one day we would sing again. I didn't know when it was Rosh ha-Shanah, but I had a sense of it when the weather turned cool. So I made a party with the bread, margarine and dirty pieces of sausage we received for meals. I said tonight will be the New Year, tomorrow a better year will come.''

Gisella later admitted: "Dr. Mengele told me that it was my duty to report every pregnant woman to him. He said that they would go to another camp for better nutrition, even for milk. So women began to run directly to him, telling him, 'I am pregnant.' I learned that they were all taken to the research block to be used as guinea pigs, and then two lives would be thrown into the crematorium. I decided that never again would there be a pregnant woman in Auschwitz... No one will ever know what it meant to me to destroy those babies, but if I had not done it, both mother and child would have been cruelly murdered.''

Anne S. Reamey has suggested that Gisella Perl made a controversial decision to deal with Mengele's experiments: "After Dr. Perl's startling realization of the fates of the pregnant women discovered by Dr. Mengele, she began to perform surgeries that before the war she would have believed herself incapable of - abortions. In spite of her professional and religious beliefs as a doctor and an observant Jew, Dr. Perl began performing abortions on the dirty floors and bunks of the barracks in Auschwitz 'using only my dirty hands'. Without any medical instruments or anesthesia, and often in the cramped and filthy bunks within the women's barracks, Dr. Perl ended the lives of the fetuses in their mothers' womb (estimated at around 3,000) in the hopes that the mother would survive and later, perhaps, be able to bear children. In some instances, the pregnancy was too far along to be able to perform an abortion. In these cases Dr. Perl broke the amnionic sac and manually dilated the cervix to induce labor. In these cases, the premature infant (not yet completely developed), died almost instantly. Without the threat of their pregnancy being discovered, women were able to work without interruption, gaining them a temporary reprieve from their death sentences."

As the war progressed Adolf Hitler became greatly concerned about the problems of production. Himmler wrote to Pohl on 5th March, 1943: "I believe that at the present time we must be out there in the factories personally in unprecedented measure in order to drive them on with the lash of our words and use our energy to assist on the spot. The Führer is counting heavily on our production and our help and our ability to overcome all difficulties, just hurl them overboard and simply produce. I ask you and Richard Glucks (head of concentration camp inspectorate) with all my heart to let no week pass by when one of you does not appear unexpectedly at this or that camp and goad, goad, goad."

The historian, Louis L. Snyder, has pointed out: "In this post he (Oswald Pohl) had charge of all concentration camps and was responsible for all works projects. He saw to it that valuables taken from Jewish inmates were returned to Germany and supervised the melting down of gold teeth taken from inmates... The railroad wagons which brought prisoners to the camps were cleaned out and used on the return journey to transfer anything of value taken from the inmates.... Gold fillings retrieved from human ashes were melted down and sent in the form of ingots to the Reichsbank for the special Max Heiliger deposit account."

Oswald Pohl formed a limited company called Eastern Industries or Osti to manage the ghetto and labour camp work shops. It has been argued that Pohl's policies prevented the deaths of thousands of concentration camp inmates. Rudolf W. Hess complained that "every new labour camp and every additional thousand workers increased the risk that one day they might be set free or somehow continue to remain alive". Reinhard Heydrich attempted to sabotage this enterprise by arranging for large numbers of Jews to be taken directly to extermination camps.

As well as the one built at Dachau concentration camps were built at Belsen and Buchenwald (Germany), Mauthausen (Austria), Theresienstadt (Czechoslovakia) and Auschwitz (Poland). Each camp was commanded by a senior Schutzstaffel (SS) officer and staffed by members of the SS Death's Head units. The camp was divided into blocks and each one was under the charge of a senior prisoner. As well as using members of the SS the camp commander often recruited Baltic or Ukrainian Germans to control inmates. As they had previously been minorities of repressed communities, they were particularly good at dealing harshly with Russians, Poles and Jews.

Heavy bombing of the camps further damaged production. Peter Padfield, the author of Himmler: Reichsfuhrer S.S. (1991) points out that Himmler suggested a possible solution to the problem: "Himmler urged Pohl to build factories for the production of war materials in natural caves and underground tunnels immune to enemy bombing, and instructed him to hollow out workshop and factory space in all SS stone quarries, suggesting that by the summer of 1944 they should have ... the greatest possible number of such 'uniquely bomb-proof work sites'... Pohl's Works' Department chief, Brigadeführer Hans Kammler, succeeded in creating underground workshops and living quarters from a cave system in the Harz mountains in central Germany."

Alfried Krupp the industrialist, made use of inmates from Auschwitz to produce goods for his company. On 19th May, 1944 he received the following report: "At Auschwitz the families were separated, those unable to work gassed, and the remainder singled out for conscription. The girls were shaved bald and tattooed with camp numbers. Their possessions, including clothing and shoes, were taken away and replaced by prison uniform and shoes. The dress was in one piece, made of grey material, with a red cross on the back and the yellow Jew-patch on the sleeve."

Inmates were used to provide medical care at the camps. Gisella Perl was a Jewish doctor at Auschwitz: "One of the basic Nazi aims was to demoralize, humiliate, ruin us, not only physically but also spiritually. They did everything in their power to push us into the bottomless depths of degradation. Their spies were constantly among us to keep them informed about every thought, every feeling, every reaction we had, and one never knew who was one of their agents. There was only one law in Auschwitz - the law of the jungle - the law of self-preservation. Women who in their former lives were decent self-respecting human beings now stole, lied, spied, beat the others and - if necessary - killed them, in order to save their miserable lives. Stealing became an art, a virtue, something to be proud of."

Rudolf Vrba escaped from Auschwitz in April 1944 and reported to the Allies: "The crematorium contains a large hall, a gas chamber and a furnace. People are assembled in the hall, which holds 2,000. They have to undress and are given a piece of soap and a towel as if they were going to the baths. Then they are crowded into the gas chamber which is hermetically sealed. Several SS men in gas masks then pour into the gas chamber through three openings in the ceiling a preparation of the poison gas maga-cyclon. At the end of three minutes all the persons are dead. The dead bodies are then taken away in carts to the furnace to be burnt."

By 1944 there were 13 main concentration camps and over 500 satellite camps. In an attempt to increase war-production, inmates were used as cheap-labour. The Schutzstaffel (SS) charged industrial companies around 6 marks for each prisoner working a twelve-hour day. In April of that year, Oswald Pohl, chief of the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office, issued orders to camp commanders: "Work must be, in the true sense of the world, exhausting in order to obtain maximum output... The hours of work are not limited. The duration depends on the technical structure of the camp and the work to be done and is determined by the camp Kommandant alone." One inmate of Auschwitz complained that Pohl was guilty of "the systematic and implacable urge to use human beings as slaves and to kill them when they could work no more."

It has been estimated that between 1933 and 1945 a total of 1,600,000 were sent to concentration work camps. Of these, over a million died of a variety of different causes. During this period around 18 million were sent to extermination camps. Of these, historians have estimated that between five and eleven million were killed.

Primary Sources

(1) Hermann Langbein, Against All Hope: Resistance in the Nazi Concentration Camps 1938-1945 (1992)

National Socialism replaced democratic institutions with a system of command and obedience, the so-called Fuhrer principle, and it was this system that the Nazis installed in their concentration camps. It goes without saying that any command by a member of the SS had to be unconditionally carried out by all prisoners. Refusal or hesitation was liable to lead to a cruel death. The camp administration not only saw to it that every command was carried out, but also held inmates assigned to certain jobs responsible for completing them. In this way it facilitated its own work and was also able to play one prisoner off against another. This system was already working when the first foreigners arrived at the camps in 1938. Each unit housing prisoners, whether a barrack or a brick building, was called a block. The camp administration held a senior block inmate (Blockdltester) responsible for enforcing discipline, keeping order, and carrying out all commands. If a dwelling unit was divided into rooms, a senior block inmate was assisted by senior barracks inmates and their staff. A senior camp inmate (Lageraltester) was responsible for the operation of the entire camp, and it was he who proposed the appointment of senior block inmates to the officer-in-charge. After the expansion of the camps, several senior camp inmates were appointed in a number of the camps, and they divided the tasks among them. Each labor detail was headed by a capo (trusty), and if the size of the detail required it, he had assistant capos or foremen under him. The capo himself was exempted from work, but he had to see to it that the required work was done by his underlings. Capos, senior block inmates, and senior camp inmates were identified by an armband with the appropriate inscription. These armband wearers, as they were generally called, were under the protection of the camp administration, often enjoyed extensive privileges, and as a rule had unlimited power over those under them. This is to be taken literally, for if an armband wearer killed an underling, he did not (with a few exceptions) have to answer to anyone, provided a timely report of the death was made and the roll call was corrected. An ordinary prisoner was completely at the mercy of his capo and senior block inmate.

As a rule the SS bestowed armbands on prisoners they could expect to be willing tools in return for their privileged status. As soon as German convicts arrived in the camps-that is, before 1938 - the SS preferred them to morally stable men. Thus, having been despised as outsiders by society all their lives, they now wielded immense power over others by virtue of a simple armband. If one of these men earned the hatred of his fellow prisoners by misusing this power, he was utterly at the mercy of the SS, for armband wearers with blood on their hands, once they lost their jobs and thus the protection of the SS, were fair game for a vengeful camp. A number of fallen capos were gang-murdered...

With years of practice behind them, many camp commandants were virtuosos at running this system. Since it was aimed at completely destroying the human dignity of anti-Nazis, a hardened criminal was able to order an anti-Nazi around as he saw fit. Such people were at the criminal's mercy when there was no SS man in the camp. Anyone who wanted to fight this system had to reduce or, if possible, abolish the effectiveness of this Fuhrer principle, as it applied to the inmates. Occasionally even some SS leaders assisted in this endeavor.

On a number of occasions, commandants and officers-in-charge could be persuaded to entrust the self-government of the inmates to prisoners without a criminal past. On the basis of his experiences in Buchenwald, Walter Poller writes: "Even some SS henchmen in the concentration camp who tried very hard to treat political prisoners in accordance with instructions could not conceal the fact that this demand of their leadership and ideology (that is, to assess political offenses as criminal ones).

(2) Harry Naujoks, My Life in Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp (1987)

Every SS guard had to be greeted by the prisoners. When a prisoner walked by an SS guard, six paces beforehand, the prisoner had to place his left hand on the seam of his trousers and with his right hand, quickly doff his cap and lay it on the seam of his trousers on the right-hand side. The prisoner had to walk by the guard while looking at him, as at attention. Three paces afterward, he was allowed to put his cap back on. This had to be done with the thumb pressed against the palm, the four fingers resting on the cap, pressed against the seam of the trousers. If this didn't happen quickly enough or the prisoner didn't snap to attention enough or his fingers weren't taut enough, or anything else happened that struck the SS guard as being insufficient, then one's ear was boxed, he had extra sports, or was reported.

(3) After the war George Topas recalled meeting for the first time Reinhold Felix, the commandant of the camp in Budzyn.

"You are fortunate to have come here. This is a good camp. Here you will work and get fed. Of course, if you expect to eat, you will have to work for it and as long as you work, you will get along fine. Now, it is prohibited to possess any silver, gold, money, or jewelry - therefore, if you turn it in now, you will not be punished."

Just at this moment, someone moved in the ranks. Felix whipped out his gun and shot him on the spot, then resumed without a pause: "Now, when I finish speaking, I want you to turn in your valuables, such as gold, silver, diamonds, and currency."

(4) Wilhelm Jäger, a doctor working for Alfried Krupp at his fuse factory at Auschwitz, reported about conditions in the camp on 15th December, 1942.

Conditions in all camps for foreign workers were extremely bad. They were greatly overcrowded. The diet was entirely inadequate. Only bad meat, such as horsemeat or meat which had been rejected by veterinarians as infected with tuberculosis germs, was passed out in these camps. Clothing, too, was altogether inadequate. Foreigners from the east worked and slept in the same clothing in which they arrived. Nearly all of them had to use their blankets as coats in cold and wet weather. Many had to to walk to work barefoot, even in winter. Tuberculosis was particularly prevalent. The TB rate was four times the normal rate. This was the result of inferior housing, poor food and an insufficient amount of it, and overwork.

(5) Witold Pilecki, an officer in the Tajna Armia Polska, the Polish Secret Army, began sending out information on what was happening in Auschwitz in October 1940.

On the way one of us was ordered to run to a post a little off the road and immediately after him went a round from a machine-gun. He was killed. Ten of his casual comrades were pulled out of the ranks and shot on the march with pistols on the ground of "collective responsibility" for the "escape", arranged by the SS-men themselves. The eleven were dragged along by straps tied to one leg. The dogs were teased with the bloody corpses and set onto them. All this to the accompaniment of laughter and jokes.

(6) Tadeusz Goldsztajn, a sixteen year old Jewish boy from Poland, began work at Alfried Krupp's fuse factory at Auschwitz in July, 1943.

At work we were Krupp's charges. SS guards were placed along the wall to prevent escape, but seldom interfered with the prisoners at work. This was the work of the various 'Meisters' and their assistants. The slightest mistake, a broken tool, a piece of scrap - things which occur every day in factories around the world - would provoke them. They would hit us, kick us, beat us with rubber hoses and iron bars. If they themselves did not want to bother with punishment, they would summon the Kapo and order him to give us twenty-five lashes. To this day I sleep on my stomach, a habit I acquired at Krupp because of the sores on my back from beating.

(7) Harry Naujoks, My Life in Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp (1987)

In normal occupancy, each barrack had 146 prisoners. This was true until mid-1938. After that, a third bed was added. Then the barrack occupancy was 180-200 men... In essence, this was case only in the first ring after 1938-1939... In other barracks, the overcrowding of the camp led to the beds being removed and the straw sacks were laid on the ground. There were also times where day rooms were covered with straw sacks at night; during the day, the straw sacks were stacked in the other room with the beds. In the large barracks, dubbed mass barracks, often 400 prisoners were jammed together.

(8) Rudolf Vrba, I Cannot Forgive (1963)

We marched into the commercial heart of Auschwitz, warehouses of the body-snachers where hundreds of prisoners worked frantically to sort, segregate and classify the clothes and the food and the valuables of those whose bodies were still burning, whose ashes would soon be used as a fertilizer.

It was an incredible sight, an enormous rectangular yard with a watchtower at each corner and surrounded by barbed wire. There were several huge storerooms and a block of what seemed like offices with a square, open balcony at one corner. Yet what first struck me was a mountain of trunks, cases, rucksacks, kitbags and parcels stacked in the middle of the yard.

Nearby was another mountain, of blankets this time, fifty thousand of them, maybe one hundred thousand. I was so staggered by the sight of these twin peaks of personal possessions that I never thought at that moment where their owners might be. In fact I did not have much time to think, for every step brought some new shock.

(9) Rudolf Höss initially concentrated on killing Red Army prisoners-of-war at Auschwitz. Later he was instructed to murder all the Jews sent to his camp.

The gassing was carried out in the detention cells of Block II. Protected by a gas-mask, I watched the killing myself. The Russians were ordered to undress in the anteroom; they then quietly entered the mortuary, for they had been told they were to be deloused. The doors were then sealed and the gas shaken down through the holes in the roof. I do not know how long this killing took. For a little while a humming sound could be heard. When the powder was thrown in, there were cries of "Gas!," then a great bellowing, and the trapped prisoners hurled themselves against both the doors. But the doors held. They were opened several hours later, so that the place might be aired. It was then that I saw, for the first time, gassed bodies in the mass.

The killing of these Russian prisoners-of-war did not cause me much concern at the time. The order had been given, and I had to carry it out. I must even admit that this gassing set my mind at rest, for the mass extermination of the Jews was to start soon and at that time neither Eichmann nor I was certain how these mass killings were to be carried out.

In the spring of 1942 the first transports of Jews, all earmarked for extermination, arrived from Upper Silesia.

It was most important that the whole business of arriving and undressing should take place in an atmosphere of the greatest possible calm. People reluctant to take off their clothes had to be helped by those of their companions who had already undressed, or by men of the Special Detachment.

Many of the women hid their babies among the piles of clothing. The men of the Special Detachment were particularly on the look-out for this, and would speak words of encouragement to the woman until they had persuaded her to take the child with her.

I noticed that women who either guessed or knew what awaited them nevertheless found the courage to joke with the children to encourage them, despite the mortal terror visible in their own eyes.

One woman approached me as she walked past and, pointing to her four children who were manfully helping the smallest ones over the rough ground, whispered: "How can you bring yourself to kill such beautiful, darling children? Have you no heart at all?"

One old man, as he passed me, hissed: "Germany will pay a heavy penance for this mass murder of the Jews." His eyes glowed with hatred as he said this. Nevertheless he walked calmly into the gas-chamber.

(10) Report sent to Alfried Krupp about conditions at Auschwitz (19th May, 1944)

At Auschwitz the families were separated, those unable to work gassed, and the remainder singled out for conscription. The girls were shaved bald and tattooed with camp numbers. Their possessions, including clothing and shoes, were taken away and replaced by prison uniform and shoes. The dress was in one piece, made of grey material, with a red cross on the back and the yellow Jew-patch on the sleeve.

(11) Hermann Langbein, Against All Hope (1992)

The prisoners had always been obliged to work, and they had been organized in labor units. Since work was intended as punishment, many of them performed meaningless tasks, the kind that really wears a person down. Only members of units that were charged with maintaining the operation of the camp and its workshops escaped such demoralizing activities as swiftly carrying rocks to a certain place and then carrying them back the same way.

To be sure, to the end, many an SS officer relapsed into his favorite pastime of tormenting prisoners by ordering them to perform meaningless tasks, but for the growing number of inmates who were placed at the disposal of the armaments industry, the nature of the work did change.

This reorganization was pursued vigorously after the defeat at Stalingrad in the winter of 1942-43, and it was stepped up as the fortunes of war declined for the Third Reich. As a result, it was necessary for each concentration camp to establish subsidiary camps at nearby arms factories. The number of such camps grew by leaps and bounds.

The reorganization produced an ambivalent attitude among the central leadership. On the one hand, the greatest possible number of "racial" prisoners were to be exterminated. On the other hand, as Himmler was to tell his Fuhrer, a growing number of prisoners were placed at the disposal of the armaments industryThis ambivalence made itself felt most strongly at Auschwitz, the camp of choice for those destined for immediate gassing. Auschwitz's four rapidly erected crematories with built-in gas chambers made such killing possible with the smallest expenditure of guards and service personnel. But because the arms industry required ever more workers, those destined for extermination were subjected to a selection process, something that was not done in the extermination camps of eastern Poland. Those who appeared to be capable of working were not immediately escorted to one of the gas chambers, but the young and strong became inmates of the camp, where they were prepared for "extermination through labor" - an expression taken from the record of a discussion between Himmler and Minister of Justice Otto Thierack in late September 1942. This record also contains the classification of the various groups of people. The purpose of the conference was to arrange for the penal system to provide as many people as possible for this "extermination through labor." This agreement obligated the German courts to supply to Himmler - in addition to Jews and Gypsies, who were first on the list - Russians, Ukrainians, and Poles with sentences of more than three years, Czechs and Germans with sentences of more than eight years, and finally the "worst antisocial elements among the last-named."

By concentrating all the extermination measures in Auschwitz and using the system of selections, this concentration camp became the largest by far. The number of Jews classified as fit for work at the admissions selections, together with other newly admitted prisoners, exceeded the number of those "exterminated through labor." This necessitated the establishment of a women's camp at Auschwitz for the female deportees who were designated as fit for work. In accordance with general practice, in March 1942 female inmates of Ravensbruck were sent to Auschwitz, together with female SS guards, to help build the camp. As a consequence of conflicting tendencies in the management of the concentration camps, one side-the Main Security Office of the Reich (Reichsssicherheitshauptamt), the central office in which Eichmann was active-pushed the deportation of Jews, and as a result crematories repeatedly broke down because of overuse. The other side-sections of the SS Main Economic and Administrative office-instructed all camp commandants to lower the mortality rate substantially, as a directive dated December 28, 1942, put it. On January 20, 1943, this directive was repeated with the following admonition: "I shall hold the camp commandant personally responsible for doing everything possible to preserve the manpower of the prisoners."

(12) In April 1944, Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler escaped from Auschwitz. Two months later they were able to publish the Vrba-Wetzler Report providing details of conditions in the camp.

The crematorium contains a large hall, a gas chamber and a furnace. People are assembled in the hall, which holds 2,000. They have to undress and are given a piece of soap and a towel as if they were going to the baths. Then they are crowded into the gas chamber which is hermetically sealed. Several SS men in gas masks then pour into the gas chamber through three openings in the ceiling a preparation of the poison gas maga-cyclon. At the end of three minutes all the persons are dead. The dead bodies are then taken away in carts to the furnace to be burnt.

(13) Walter Kramer, statement made at American Military Headquarters in Marburg, Germany (September, 1945)

In Danzig we were unloaded onto old barges in which the water was twenty centimetres deep. One tugboat drew the four barges up the Vistula to the notorious concentration camp of Stutthof. The camp S.S. immediately took us into custody. They took everything from us; we didn't keep even a belt and had to fasten our pants with twine. They led us to Compound Three, designed for two hundred fifty men, but we filled it with nine hundred. There were only three-level bunk beds - four men on the bottom, three in the middle and three more on the top. I always slept at top, for at least up there you don't get whipped so easily by the compound superior. The first two days we got nothing at all to eat.

In a camp such as Stutthof where there were forty-five thousand prisoners nine hundred didn't matter very much. Everything to speed our deaths. . . . One evening we had just lain down in our bunks when we had to line up for roll call. We simply stormed out of the barracks and the billy clubs did their work. Then right about face and to the gallows; forty-five thousand men were kicked out of bed to watch a prisoner being hanged for violation of camp rules.

(14) Richard Dimbleby, BBC radio broadcast from Belsen (19th April 1945)

I picked my way over corpse after corpse in the gloom, until I heard one voice raised above the gentle undulating moaning. I found a girl, she was a living skeleton, impossible to gauge her age for she had practically no hair left, and her face was only a yellow parchment sheet with two holes in it for eyes. She was stretching out her stick of an arm and gasping something, it was "English, English, medicine, medicine", and she was trying to cry but she hadn't enough strength. And beyond her down the passage and in the hut there were the convulsive movements of dying people too weak to raise themselves from the floor.

In the shade of some trees lay a great collection of bodies. I walked about them trying to count, there were perhaps 150 of them flung down on each other, all naked, all so thin that their yellow skin glistened like stretched rubber on their bones. Some of the poor starved creatures whose bodies were there looked so utterly unreal and inhuman that I could have imagined that they had never lived at all. They were like polished skeletons, the skeletons that medical students like to play practical jokes with.

At one end of the pile a cluster of men and women were gathered round a fire; they were using rags and old shoes taken from the bodies to keep it alight, and they were heating soup over it. And close by was the enclosure where 500 children between the ages of five and twelve had been kept. They were not so hungry as the rest, for the women had sacrificed themselves to keep them alive. Babies were born at Belsen, some of them shrunken, wizened little things that could not live, because their mothers could not feed them.

One woman, distraught to the point of madness, flung herself at a British soldier who was on guard at the camp on the night that it was reached by the 11th Armoured Division; she begged him to give her some milk for the tiny baby she held in her arms. She laid the mite on the ground and threw herself at the sentry's feet and kissed his boots. And when, in his distress, he asked her to get up, she put the baby in his arms and ran off crying that she would find milk for it because there was no milk in her breast. And when the soldier opened the bundle of rags to look at the child, he found that it had been dead for days.

There was no privacy of any kind. Women stood naked at the side of the track, washing in cupfuls of water taken from British Army trucks. Others squatted while they searched themselves for lice, and examined each other's hair. Sufferers from dysentery leaned against the huts, straining helplessly, and all around and about them was this awful drifting tide of exhausted people, neither caring nor watching. Just a few held out their withered hands to us as we passed by, and blessed the doctor, whom they knew had become the camp commander in place of the brutal Kramer.

(15) Peter Combs was a British soldier who witnessed the liberation of Belsen. He wrote about what he saw in a letter to his wife in April 1945.

The conditions in which these people live are appalling. One has to take a tour round and see their faces, their slow staggering gait and feeble movements. The state of their minds is plainly written on their faces, as starvation has reduced their bodies to skeletons. The fact is that all these were once clean-living and sane and certainly not the type to do harm to the Nazis. They are Jews and are dying now at the rate of three hundred a day. They must die and nothing can save them - their end is inescapable, they are far gone now to be brought back to life.

(16) Manchester Guardian (1st May, 1945)

The capture of the notorious concentration camp near Dachau, where approximately 32,000 persons were liberated, was announce in yesterday's S.H.A.E.F. communiqué. Three hundred S.S. guards at the camp were quickly overcome it said.

A whole battalion of Allied troops was needed to restrain the prisoners from excesses. Fifty railway trucks crammed with bodies and the discovery of gas chambers, torture rooms, whipping posts, and crematoria strongly support report which had leaked out of the camp.

An Associated Press correspondent with the Seventh Army says that many of the prisoners seized the guards' weapons and revenged themselves on the SS men. Many of the well-known prisoners, it was said, had been recently removed to a new camp in the Tyrol.

Prisoners with access to the records said that 9,000 died of hunger and disease, or were shot in the past three months and 4,000 more perished last winter.

(17) Martha Gellhorn was with the United States troops that liberated Dachau in 1945. She later wrote about it in her book The Face of War (1959)

I have not talked about how it was the day the American Army arrived, though the prisoners told me. In their joy to be free, and longing to see their friends who had come at last, many prisoners rushed to the fence and died electrocuted. There were those who died cheering, because that effort of happiness was more than their bodies could endure. There were those who died because now they had food, and they ate before they could be stopped, and it killed them. I do not know words to describe the men who have survived this horror for years, three years, five years, ten years, and whose minds are as clear and unafraid as the day they entered.

I was in Dachau when the German armies surrendered unconditionally to the Allies. We sat in that room, in that accursed cemetery prison, and no one had anything more to say. Still, Dachau seemed to me the most suitable place in Europe to hear the news of victory. For surely this war was made to abolish Dachau, and all the other places like Dachau, and everything that Dachau stood for, and to abolish it for ever.