Recruitment in the First World War

On the outbreak of war in August 1914, Britain had 247,432 regular troops. About 120,000 of these were in the British Expeditionary Army and the rest were stationed abroad. It was clear that more soldiers would be needed to defeat the German Army.

On 7th August, 1914, Lord Kitchener, the war minister, immediately began a recruiting campaign by calling for men aged between 19 and 30 to join the British Army. At first this was very successful with an average of 33,000 men joining every day. Three weeks later Kitchener raised the recruiting age to 35 and by the middle of September over 500,000 men had volunteered their services.

The leadership of the Women's Social & Political Union (WSPU) began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Annie Kenney reported that orders came from Christabel Pankhurst: "The Militants, when the prisoners are released, will fight for their country as they have fought for the Vote." Kenney later wrote: "Mrs. Pankhurst, who was in Paris with Christabel, returned and started a recruiting campaign among the men in the country. This autocratic move was not understood or appreciated by many of our members. They were quite prepared to receive instructions about the Vote, but they were not going to be told what they were to do in a world war."

Emmeline Pankhurst announced that all militants had to "fight for their country as they fought for the vote." Ethel Smyth pointed out in her autobiography, Female Pipings for Eden (1933): "Mrs Pankhurst declared that it was now a question of Votes for Women, but of having any country left to vote in. The Suffrage ship was put out of commission for the duration of the war, and the militants began to tackle the common task."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men.At the beginning of the war the army had strict specifications about who could become soldiers. Men joining the army had to be at least 5ft 6in tall and a chest measurement of 35 inches. By May 1915 soldiers only had to be 5ft 3in and the age limit was raised to 40. In July the army agreed to the formation of 'Bantam' battalions, composed of men between 5ft and 5ft 3in in height.

With the outbreak of the war, Horatio Bottomley told his personal assistant, Henry J. Houston: "Houston, this war is my opportunity. Whatever I have been in the past, and whatever my faults, I am going to draw a line at August 4th, 1914, and start afresh. I shall play the game, cut all my old associates, and wipe out everything pre-1914" Houston later recalled: "At the time I thought he meant it, but but now I know that the flesh, habituated to luxury and self-indulgence, was too weak to give effect to the resolution. For a while he did try to shake off his old associates, but the claws of the past had him grappled in steel, and the effort did not last more than a few weeks."

In September 1914, the first recruiting meetings were held in London. The first meetings were addressed by government ministers. Bottomley told Houston: "These professional politicians don't understand the business. I am going to constitute myself the Unofficial Recruiting Agent to the British Empire. We must have a big meeting." His first meeting at the Albert Hall was so popular that according to Houston, Bottomley "was unable for two hours to get into his own meeting."

Bottomley wrote to Herbert Henry Asquith about the possibility of becoming Director of Recruiting. Asquith replied: "Thank you for your offer but I shall not avail myself of it at the moment. You are doing better work where you are." Asquith, aware of his popularity, encouraged him to do this work in an unofficial capacity. It has been claimed at the time that he was paid between £50 and £100 to address meetings where he encouraged young men to join the armed forces. Henry J. Houston claimed that he spoke at the Empire Theatre, Leicester Square, and delivered a ten minutes' speech each night for a week at a fee of £600. Later, Bottomley "secured a week's engagement, two houses nightly, at the Glasgow Pavilion, where he received a fee of £1,000."

In one speech Horatio Bottomley argued: "Every hero of the war who has fallen in the field of battle has performed an Act of Greatest Love, so penetrating and intense in its purifying character that I do not hesitate to express my opinion that any and every past sin is automatically wiped out from the record of his life." George Bernard Shaw went to one of Bottomley's meetings and afterwards commented: "It's exactly what I expected: the man gets his popularity by telling people with sufficient bombast just what they think themselves and therefore want to hear."

In 1914 David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was given the task of setting up a British War Propaganda Bureau (WPB). Lloyd George, appointed the successful writer and fellow Liberal MP, Charles Masterman as head of the organization. The WPB arranged for journalists like Bottomley to visit the Western Front. The WPB arranged for journalists like Bottomley to visit the Western Front.

It has been calculated that Horatio Bottomley addressed twenty recruiting meetings and 340 "patriotic war lectures". Although he had been highly critical of the government, at the meetings he always stated: "When the country is at war, it is the duty of every patriot to say: My country right or wrong; My government good or bad." He also falsely claimed that he was "not going to take money for sending men out to their death, or profit from his country in its hour of need." Bottomley claimed that he used the meetings to publicise John Bull Magazine and according to Houston, he drew over £22,000 from the journal for his efforts.

At one meeting a man in the audience shouted out: "Isn't it time you went and did your bit, Mr. Bottomley?" Bottomley replied: "Would to God it were my privilege to shoulder a rifle and take my place beside the brave boys in the trenches. But you have only to look at me to see that I am suffering from two complaints. My medical man calls them anno domini and embonpoint. The first means that I was born too soon and the second that my chest measurement has got into the wrong place."

To persuade young men to join the armed forces Horatio Bottomley gave the impression that the war would be over in a few weeks. In a speech at the Bournemouth Winter Gardens in September, 1915, he argued: "Ladies and gentlemen, I want you to pull yourselves together and keep your peckers up. I want to assure you that within six weeks of to-day we shall have the Huns on the run. We shall drive them out of France, out of Flanders, out of Belgium, across the Rhine, and back into their own territory. There we shall give them a taste of their own medicine. Bear in mind, I speak of that which I know. Tomorrow it will be officially denied, but take it from me that if Bottomley says so, it is so!"

Henry J. Houston argued in his book, The Real Horatio Bottomley (1923): "He began to accept what were practically music hall engagements disguised as recruiting meetings, and I was very definitely of the opinion that he was drifting in the wrong direction. Nevertheless for some time it went on... Bottomley insisted that a substantial contribution (from the income generated from the meetings) went to his War Charity Fund... Three years later I discovered that the fund did not receive a penny of the money."

During the first few months of the war the War Propaganda Bureau published pamphlets such as the Report on Alleged German Outrages, that gave credence to the idea that the German Army had systematically tortured Belgian civilians. Other pamphlets published by the WPB that helped with recruitment included To Arms! (Arthur Conan Doyle), The Barbarism in Berlin (G. K. Chesterton), The New Army (Rudyard Kipling) and Liberty, A Statement of the British Case (Arnold Bennett).

The British government also began a successful poster campaign. Artists such as Saville Lumley, Alfred Leete, Frank Brangwyn and Norman Lindsay, produced a series of posters urging men to join the British Army. The desire to fight continued into 1915 and by the end of that year some two million men had volunteered their services.

In October 1915, the WSPU changed its newspaper's name from The Suffragette to Britannia. Emmeline's patriotic view of the war was reflected in the paper's new slogan: "For King, For Country, for Freedom'. In the newspaper anti-war activists such as Ramsay MacDonald were attacked as being "more German than the Germans". Another article on the Union of Democratic Control and Norman Angell carried the headline: "Norman Angell: Is He Working for Germany?" Mary Macarthur and Margaret Bondfield were described as "Bolshevik women trade union leaders" and Arthur Henderson, who was in favour of a negotiated peace with Germany, was accused of being in the pay of the Central Powers.

Primary Sources

(1) Lionel Ferguson, joined the British Army in Liverpool, interview (1978)

That afternoon I decided to join the Liverpool Scottish. What sights I saw on my way up to Frazer Street: a queue of men over two miles long in the Haymarket; the recruiting office took over a week to pass in all those thousands. At the Liverpool Scottish HQ things seemed hopeless; in fact I was giving up hopes of ever getting in, when I saw Rennison, an officer of the battalion, and he invited me into the mess, getting me in front of hundreds of others. I counted myself in luck to secure the last kilt, which although very old and dirty, I carried away to tog myself in.

(2) George Coppard was sixteen when he joined the Royal West Surrey Regiment in August, 1914.

Although I seldom saw a newspaper, I knew about the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand at Sarajevo. News placards screamed out at every street corner, and military bands blared out their martial music in the main streets of Croydon. This was too much for me to resist, and as if drawn by a magnate, I knew I had to enlist straight away.

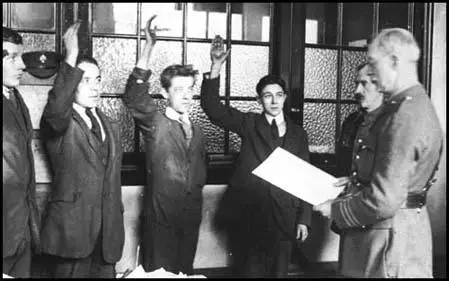

I presented myself to the recruiting sergeant at Mitcham Road Barracks, Croydon. There was a steady stream of men, mostly working types, queuing to enlist. The sergeant asked me my age, and when told, replied, "Clear off son. Come back tomorrow and see if you're nineteen, eh?" So I turned up again the next day and gave my age as nineteen. I attested in a batch of a dozen others and, holding up my right hand, swore to fight for King and Country. The sergeant winked as he gave me the King's shilling, plus one shilling and ninepence ration money for that day.

(3) Robert Sherriff, No Leading Lady (1968)

The Adjutant came in. He sorted out some papers on his table and called for the first applicant to come forward. "School?" inquired the adjutant. "Winchester,"replied the boy.

"Good," said the adjutant. There was no more to say. Winchester was one of the most renowned schools in England. He filled in a few details on a form and told the boy to report to the medical officer for routine examination. He was practically an officer. In a few days his appointment would come through...

My turn came.

"School?" inquired the adjutant. I told him, and his face fell. He took up a printed list from his desk and searched through it. "I'm sorry," he said, "but I'm afraid it isn't a public school."

And that was that. I was told to go to another room where a sergeant major was enlisting recruits for the ranks.

(4) John Reith, Wearing Spurs (1966)

In a sense I had been looking forward to war, and for years; now it was coming. It was an entirely personal affair; no thought of what it might mean to home, or country, or civilisation.

I was a week over twenty-five, and in a thoroughly unsettled state anyhow. My family had decided that I should be an engineer; and, though I knew it was all wrong, I had no reasonable alternative to advance. Having begun the long apprenticeship, however unattractive and even distasteful the prospect, I was determined to see it through; and did. And then, having acquired the recognised qualifications theoretical and practical of an engineer, despite strong family discouragement, but because I was sure there was nothing for me in Glasgow, I had made for London. There, six months earlier, I had joined the great Pearson contracting firm, or rather had gotten a job from them. But the future was displeasing. That very week the discovery that my chief, the sub-agent, with fifteen years' service, was drawing only £250 per annum had numbered my days with Pearson's; new arrangements were well in hand. War. The problem for the time being was otherwise solved.

(5) Reverend George Reith, letter to John Reith (14th November, 1914)

It is rather a shock to your mother and me to find that you are off to the Front; and we can only pray God to be with you every moment; to give you strength and comfort and confidence in every duty to be laid upon you; and to let the assurance of Christ's presence sustain you in every hour of danger. You are doing a great work in defending your country - the greatest honour that can come to men in this world, or one of them at least. Our country's glory and good name are committed to your care for the time; and the mere thought of that should inspire you with high resolve to do all you can do. And then the cause is a righteous one if ever there were a righteous cause. God is and must be on our side as we contend for honour and faithfulness among nations; and we shall be on His side if in our own hearts we repent of all our national sins and seek that this terrible business be overruled for our spiritual welfare as a people. Keep close to Christ, dear boy. Make sure that your heart is His; that whatever happens you are fighting under Him as captain; no ill can befall you then.

(6) Manchester Guardian (18th August, 1914)

A battalion is being raised composed entirely of employees in Manchester offices and warehouses upon the ordinary conditions of enlistment in Lord Kitchener's army, namely, for three years, or the duration of the War.

The Battalion will be clothed and equipped (excepting arms) by a fund being raised for the purpose. We therefore desire to call the attention of all our employees between the ages of 19 and 35 years to the call of Lord Kitchener, which was emphasized by the Prime Minister in the House of Commons, for further recruits, and, in order to encourage enlistment, we are prepared to offer to all employees enlisting within the next two weeks the following conditions:

(1) four weeks' full wages from date of leaving.

(2) re-engagement on discharge from service guaranteed.

(3) half pay during absence on duty for married men from the date that full pay ceases, to be paid to the wife.

(4) Special arrangements made for single men who have relatives entirely dependent on them.

(5) The above payments only apply to those enlisting in the Ranks, and not to anyone who may obtain a commission otherwise than by promotion from the Ranks, but each case (if any) of those obtaining a commission, will be treated on its merits.

(6) The above offer is for voluntary service only, and should the Government decide on compulsory training later, the offer will not apply to those affected by such compulsion.

(7) George Buxton, letter to brother (January, 1915)

There is no sin in volunteering. God means us to stand up for everything that's right, and if every Christian is going to stand out of the firing line because he thinks it's not for him, then what is left? It's a great mistake to say Christians shouldn't carry a rifle. I should hate to kill anybody, but then those carrying rifles are not murderers, they equally are human and don't love killing others, they do it because it's their duty. Especially in this war, where our cause is right, we didn't make the war, the blame doesn't rest on us, Germany forced it and will undoubtedly be punished by God.

(8) Private George Morgan, Ist Bradford Pals, interviewed after the war.

We had been brought up to believe that Britain was the best country in the world and we wanted to defend her. The history taught us at school showed that we were better than other people and now all the news was that Germany was the aggressors and we wanted to show the Germans what we could do.

I thought it would be the end of the world if I didn't pass (the medical). People were being failed for all sorts of reasons. When I came to have my chest measured (I was only sixteen and rather small) I took a deep breath and puffed out my chest as far as I could and the doctor said "You've just scraped through". It was marvellous being accepted.

When I went back home and told my mother she said I was a fool and she'd give me a good hiding; but I told her, "I'm a man now, you can't hit a man".

(9) Second Lieutenant Cyril Rawlins, letter to mother (December, 1914)

Now, dearest mum, keep your heart up, and trust in Providence: I am sure I shall come through all right. It is a great and glorious thing to be going to fight for England in her hour of desperate need and, remember, I am going to fight for you, to keep you safe.

(10) Henry J. Houston, The Real Horatio Bottomley (1923)

These lectures were organized on a strictly business basis. The usual terms made with the proprietors of halls all over the United Kingdom stipulated for anything between 65 per cent. and 85 per cent. of the gross takings for admission, the proprietors providing the poster display, advertising, music, lighting and hall.

In addition to the "gate" receipts, H.B. received remuneration from the proprietors of John Bull on the following basis. One meeting per day, £25; two meetings per day, £17 Z10s. per meeting. Poster displays, amounting to many hundreds of pounds in cost, were also supplied by John Bull without charge.

It will thus be seen that the war provided H.B. with an excellent source of revenue. The expenditure of nervous and physical energy involved in the lecture tour was enormous. Every night when I got him away from a meeting to the hotel I had to strip him and give him a thorough towelling. He was invariably saturated right through to his morning coat with perspiration.

He needed a great deal of care as a result, and I found it necessary to travel special blankets for him. The first thing I used to do when we arrived at a hotel was to place the special blankets on his bed. That was done mainly at the request of Mrs. Bottomley, but it was a necessary precaution...

In September, 1915, we travelled down to Bournemouth to address our first two meetings, one in the afternoon and the other in the evening at the Winter Gardens controlled by Sir (then Mr.) Dan Godfrey...

Early next morning we motored on to Torquay, where he addressed two more meetings at a profit of £212, and caught the sleeping car back to London the same night.

"This opens up a new source of income, Houston," he said to me, as we discussed the lectures in the train." It has surprised even you, hasn't it? You must set to work in earnest now and get me booked up three days a week all over the country."

His energy was unbounded, and for days he was desperately restless because a short time had to elapse before all the arrangements could be completed.

"Why can't we get to work at once, Houston?" he exclaimed impatiently. "We are losing money and wasting time."

Before many days had passed I had fixed as many meetings as he could manage. We went on to Margate and other places, the receipts usually being about £100 a meeting. Then, on the first Sunday in October, we went to Blackpool, where he addressed two meetings and came away with about £300! On several occasions afterwards we revisited Blackpool, and he was always certain of making £300.

Gradually money became the ruling passion with H.B. in connection with the lectures. It was an obsession with him. If I arranged a big evening meeting for him in a large town, he would insist on My arranging an afternoon meeting on the same day at some neighbouring place, even if it was quite a small place, where he could not hope to make more than £40.

(11) Horatio Bottomley, speech at the Bournemouth Winter Gardens (September, 1915)

Ladies and gentlemen, I want you to pull yourselves together and keep your peckers up. I want to assure you that within six weeks of to-day we shall have the Huns on the run. We shall drive them out of France, out of Flanders, out of Belgium, across the Rhine, and back into their own territory. There we shall give them a taste of their own medicine. Bear in mind, I speak of that which I know. Tomorrow it will be officially denied, but take it from me that if Bottomley says so, it is so!

Student Activities

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)