British Journalism and the First World War

At the end of July, 1914, it became clear to the British government that the country was on the verge of war with Germany. Four senior members of the government, Charles Trevelyan, David Lloyd George, John Burns, and John Morley, were opposed to the country becoming involved in a European war and they informed the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, that they intended to resign over the issue. When war was declared on 4th August, three of the men, Trevelyan, Burns and Morley, resigned, but Asquith managed to persuade Lloyd George, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, to change his mind.

David Lloyd George now became one of the main figures in the government willing to escalate the war in an effort to bring an early victory. Lloyd George was quick to realize that it would be important to persuade newspaper editors to fully support the war. His most important achievement was to persuade C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, to give its backing to the government. Scott, like Lloyd George, had been one of the leaders of the anti-war group during the Boer War. Charles Trevelyan was especially disappointed with Scott's change of views as he had expected the Manchester Guardian to support his anti-war organisation, the Union of Democratic Control (UDC).

Lord Kitchener, the War Minister, was determined not to have any journalists reporting the war from the Western Front. He instead appointed Colonel Ernest Swinton, to write reports on the war. These were then vetted by Kitchener before being sent to the newspapers. Later in 1914, Henry Major Tomlinson, a journalist working for the Daily News, was recruited by the British Army as its official war correspondent.

Some journalists were already in France when war was declared in August 1914. Philip Gibbs, a journalist working for The Daily Chronicle, quickly attached himself to the British Expeditionary Force and began sending in reports from the Western Front. When Lord Kitchener discovered what was happening he ordered the arrest of Gibbs. After being warned that if he was caught again he "would be put up against a wall and shot", Gibbs was sent back to England.

Hamilton Fyfe of the Daily Mail and Arthur Moore of The Times managed to send back reports but these were rewritten by F. E. Smith, the head of the government's Press Bureau. Smith often manipulated the stories in order to shape public opinion. For example, in Moore's report on the Battle of Mons, Smith added the passage: "The BEF requires immediate and immense reinforcement. It needs men, men, and yet more men. We want reinforcements and we want them now."

Other journalists such as William Beach Thomas of the Daily Mail and Geoffrey Pyke of Reuters, who were still in France, were arrested and accused by the British authorities of being spies. Henry Hamilton Fyfe of the Daily Mail was also threatened with arrest and he overcame the problem by joining the French Red Cross as a stretcher bearer. In this way he was able to continue reporting on the war in France for a couple more months. However, the British military caught up with Fyfe and he decided to leave and report on the Eastern Front where journalists were still able to report on the war without restrictions.

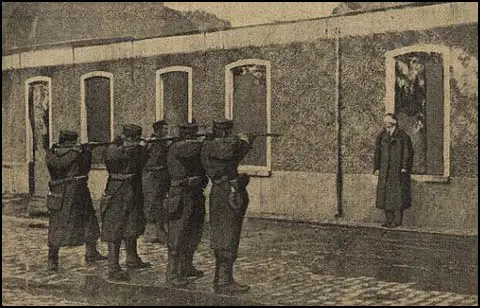

Albert Rhys Williams was an American journalist in Belgium in 1914. He was asked by another journalist: "Wouldn't you like to have a photograph of yourself in these war-surroundings, just to take home as a souvenir?" The idea appealed to him. After rejecting some commonplace suggestions, the journalist exclaimed: "I have it. Shot as a German Spy. There's the wall to stand up against; and we'll pick a crack firing-squad out of these Belgians."

Williams later recalled: "I acquiesced in the plan and was led over to the wall while a movie-man whipped out a handkerchief and tied it over my eyes. The director then took a firing squad in hand. He had but recently witnessed the execution of a spy where he had almost burst with a desire to photograph the scene. It had been excruciating torture to restrain himself. But the experience had made him feel conversant with the etiquette of shooting a spy, as it was being done amongst the very best firing-squads. He made it now stand him in good stead." A week later the photograph appeared in the Daily Mirror. It included the caption: "The Belgians have a short, sharp method of dealing with the Kaiser's rat-hole spies. This one was caught near Termonde and, after being blindfolded, the firing-squad soon put an end to his inglorious career."

In January, 1915, the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, received a letter from the former American president, Theodore Roosevelt. He warned Grey that the policy of preventing journalists from reporting the war was "harming Britain's cause in the United States." After a Cabinet meeting on the subject, the government decided to change its policy and to allow selected journalists to report the war. Five men were chosen: Philip Gibbs (Daily Chronicle and the Daily Telegraph), Percival Philips (Daily Express and the Morning Post), William Beach Thomas (Daily Mail and the Daily Mirror) Henry Perry Robinson (The Times and the Daily News) and Herbert Russell (Reuters News Agency). Before their reports could be sent back to England, they had to be submitted to C. E. Montague, the former leader writer of the Manchester Guardian.

Over the next three years other journalists such as John Buchan, Valentine Williams, Hamilton Fyfe and Henry Nevinson, became accredited war correspondents. To remain on the Western Front, these journalists had to accept government control over what they wrote. Even the disastrous first day of the Battle of the Somme was reported as a victory. Later William Beach Thomas admitted that he was "deeply ashamed of what he had written" but Philip Gibbs defended his actions by claiming that he was attempting to "spare the feelings of men and women, who, have sons and husbands fighting in France".

After the war most of the accredited war correspondents were offered knighthoods by George V. Some like Philip Gibbs, Herbert Russell, Henry Perry Robinson and William Beach Thomas, agreed to accept the offer. However, others like Hamilton Fyfe, Robert Donald and Henry Nevinson refused. Fyfe saw it as a bribe to keep quiet about the inefficiency and corruption he had witnessed during the war, whereas Nevinson feared it might influence his freedom to report political issues in the future.

Primary Sources

(1) On the 4th September, 1914, C. P. Scott, recorded details of a meeting he had with David Lloyd George that day.

He (Lloyd George), Beauchamp, Morley and Burns had all resigned from the Cabinet on the Saturday (1st August) before the declaration of war on the ground that they could not agree to Grey's pledge to Cambon (the French ambassador in London) to protect north coast of France against Germans, regarding this as equivalent to war with Germany. On urgent representations of Asquith he (Lloyd George) and Beauchamp agreed on Monday evening to remain in the Cabinet without in the smallest degree, as far as he was concerned, withdrawing his objection to the policy but solely in order to prevent the appearance of disruption in face of a grave national danger. That remains his position. He is, as it were, an unattached member of the Cabinet.

(2) In the early months of the war the War Office tried to prevent journalist in France from sending reports back to England. Philip Gibbs was arrested at Le Havre on the way back to the Western Front.

During the early months of the war in 1914 there was a conflict of opinion between the War Office and the Foreign Office regarding news from the Front. The War Office wanted to black out all but the official communiqués, and some innocuous articles by an official eye-witness (Ernest Swinton). A friend in the War Office warned me that I was in Kitchener's black books, and that orders had been given for my arrest next time I appeared in France.

All was well, until I reached the port of Havre. Three officers with the rank of lieutenant, whom afterwards I knew to be Scotland Yard men, came aboard and demanded to see my papers which they took away from me. I was arrested and taken into the presence of General Bruce Williams in command of the base at Havre. He was very violent in his language, and said harsh things about newspaper fellows who defied all orders, and wandered about the war zone smuggling back uncensored nonsense. He had already rounded up some of them and had a good mind to have us all shot against a white wall.

He put me under house arrest in the Hotel Tortoni, in charge of six Scotland Yard men who had their headquarters there. Meanwhile, before receiving instructions what to do with me, General Bruce Williams forbade me all communication with Fleet Street or my family. For nearly a fortnight I kicked my heels about in the Hotel Tortoni, standing drinks to the Scotland Yard men, who were very decent fellows, mostly Irish. One of them became quite a friend of mine and it was due to him that I succeeded in getting a letter to Robert Donald, explaining my plight. He took instant action and, by the influence of Lord Tyrell at the Foreign Office, I was liberated and allowed to return to England.

The game was up, I thought. I had committed every crime against War Office orders. I should be barred as a war correspondent when Kitchener made up his mind to allow them out. So I believed, but in the early part of 1915 I was appointed one of the five men accredited as official war correspondents with the British Armies in the Field.

(3) In September, 1914, Arthur Moore of The Times and Hamilton Fyfe of the Daily Mail, managed to write accounts of the Battle of the Mons. Moore sent a note to his editor, Henry Wickham Steed, explaining why his report should be published.

I read this afternoon in Amiens this morning's Paris papers. To me, knowing some portion of the truth, it seemed incredible that a great people should be kept in ignorance of the situation which it had to face. It is important that the nation should know and realize certain things. Bitter truths, but we can face them. We have to cut our losses, to take stock of the situation.

(4) In early September, 1914, Hamilton Fyfe of the Daily Mail and Arthur Moore of The Times, met up with the British Expeditionary Force and observed the early success of the German Army.

Driving from Boulogne we saw British soldiers and we heard the whole story. Orders had been given for a hasty retreat of all the British troops in and about Amiens. What had happened? They shrugged their shoulders. Where were they going? They didn't know. What Arthur Moore (The Times) and I felt instantly was that we had to know. There was nothing to keep us out of Amiens now. In less than two hours we were there, listening to the sound of not very distant guns. We drove about all that day seeking for news and realizing every hour more and more clearly the disaster that had happened. We saw no organized bodies of troops, but we met and talked to many fugitives in twos and threes, who had lost their units in disorderly retreat and for the most part had no idea where they were.

That Friday night, tired as we were, Moore and I set off to Diepppe to put our messages on a boat which we knew would be leaving on the Saturday morning. They reached London on Saturday morning. They reached London on Saturday night. Both were published in The Times next day. (The Times was then published on Sunday; the Mail was not.)

As they gave the first news of the defeat they must in any case have caused a sensation. But the sensation would not have been so painful if Lord Birkenhead, then F. E. Smith, had not been Press Censor at the time. The despatches were taken to him after dinner. When the man who took them told me about it later on, he said, "After dinner - you know what that meant with him."

Birkenhead saw that they must be published. He saw the intention with which they had been written - to rouse the nation to a sense of the need for greater effort. But he seemed to think that it would be better to suggest disaster by the free use of dots than to let the account appear in coherent and constructive form. With unsteady hand he struck out sentences and parts of sentences, substituting dots for them, and thus making it appear that the truth was far worse than the public could be allowed to know.

(5) In September 1914, Lord Kitchener, Britain's War Minister, banned journalists from the Western Front. Hamilton Fyfe attempted to overcome this problem by joining the Red Cross.

The ban on correspondents was still being enforced, so I joined a French Red cross detachment as a stretcher bearer, and though it was hard work, managed to send a good many despatches to my paper. I had no experience of ambulance or hospital work, but I grew accustomed to blood and severed limbs and red stumps very quickly. Only once was I knocked out. We were in a schoolroom turned into a operating theatre. It was a hot afternoon. We had brought in a lot of wounded men who had been lying in the open for some time; their wounds crawled with lice. All of us had to act as aids to our two surgeons. Suddenly I felt the air had become oppressive. I felt I must get outside and breathe. I made for the door, walked along the passage. Then I found myself lying in the passage with a big bump on my head. However, I got rid of what was troubling my stomach, and in a few minutes I was back in the schoolroom. I did not suffer in that way again.

What caused me discomfort far more acute - because it was mental, not bodily - were the illustrations of the bestiality, the futility, the insanity of war and of the system that produced war as surely as land uncultivated produces noxious weeds: these were now forced on my notice every day. The first cart of dead that I saw, legs sticking out stiffly, heads lolling on shoulders, all the poor bodies shovelled into a pit and covered with quicklime, made me wonder what the owners had been doing when they were called up, crammed into uniforms, and told to kill, maim, mutilate other men like themselves, with whom they had no quarrel. All of them had left behind many who would be grieved, perhaps beggared, by their taking off. And all to no purpose, for nothing.

(6) Philip Gibbs, The Pageant of the Years (1946)

One of the censors was C. E. Montague, the most brilliant leader writer and essayist on the Manchester Guardian before the war. Prematurely white-haired, he had dyed it when the war began and had enlisted in the ranks. He became a sergeant and then was dragged out of his battalion, made a captain, and appointed as censor to our little group. Extremely courteous, abominably brave - he liked being under shell fire - and a ready smile in his very blue eyes, he seemed unguarded and open.

Once he told me that he had declared a kind of moratorium on Christian ethics during the war. It was impossible, he said, to reconcile war with the Christian ideal, but it was necessary to get on with its killing. One could get back to first principles afterwards, and resume one's ideals when the job had been done.

(7) Albert Rhys Williams, In the Claws of the German Eagle (1917)

While his little army rested from their manoeuvers the Director-in-Chief turned to me and said:

"Wouldn't you like to have a photograph of yourself in these war-surroundings, just to take home as a souvenir?"

That appealed to me. After rejecting some commonplace suggestions, he exclaimed: "I have it. Shot as a German Spy. There's the wall to stand up against; and we'll pick a crack firing-squad out of these Belgians. A little bit of all right, eh ?"

I acquiesced in the plan and was led over to the wall while a movie-man whipped out a handkerchief and tied it over my eyes. The director then took a firing squad in hand. He had but recently witnessed the execution of a spy where he had almost burst with a desire to photograph the scene. It had been excruciating torture to restrain himself. But the experience had made him feel conversant with the etiquette of shooting a spy, as it was being done amongst the very best firing-squads. He made it now stand him in good stead.

"Aim right across the bandage," the director coached them. I could hear one of the soldiers laughing excitedly as he was warming up to the rehearsal. It occurred to me that I was reposing a lot of confidence in a stray band of soldiers. Some one of those Belgians, gifted with a lively imagination, might get carried away with the suggestion and act as if I really were a German spy...

A week later I picked up the London Daily Mirror from a news-stand. I opened up the paper and what was my surprise to see a big spread picture of myself, lined up against that row of Melle cottages and being shot for the delectation of the British public. There is the same long raincoat that runs as a motif through all the other pictures. Underneath it were the words: "The Belgians have a short, sharp method of dealing with the Kaiser's rat-hole spies. This one was caught near Termonde and, after being blindfolded, the firing-squad soon put an end to his inglorious career."

One would not call it fame exactly, even though I played the star-role. But it is a source of some satisfaction to have helped a royal lot of fellows to a first-class scoop. As the "authentic spy-picture of the war," it has had a broadcast circulation. I have seen it in publications ranging all the way from The Police Gazette to Collier's Photographic History of the European War. In a university club I once chanced upon a group gathered around this identical picture. They were discussing the psychology of this "poor devil" in the moments before he was shot. It was a further source of satisfaction to step in and arbitrarily contradict all their conclusions and, having shown them how totally mistaken they were, proceed to tell them exactly how the victim felt. This high-handed manner nettled one fellow terribly.

(8) Philip Gibbs, The Pageant of the Years (1946)

Our worst enemy for a time was Sir Douglas Haig. He had the old cavalry officers' prejudice against war correspondents and "writing fellows", and made no secret of it. When he became Commander-in-Chief he sent for us and said things which rankled. One of them was that "after all you are only writing for Mary Ann in the kitchen."

I would not let him get away with that, and told him that it was not only for Mary Ann that we were writing, but for the whole nation and Empire, and that he could not conduct his war in secret, as though the people at home, whose sons and husbands were fighting and dying, had no concern in the matter. The spirit of the fighting men, and the driving power behind the armies, depended upon the support of the whole people and their continuing loyalties.

(9) C. P. Scott, recorded in his diary comments made by David Lloyd George after he had heard Philip Gibbs speak at a private meeting on 27th December, 1917.

I listened last night, at a dinner given to Philip Gibbs on his return from the front, to the most impressive and moving description from him of what the war (on the Western Front) really means, that I have heard. Even an audience of hardened politicians and journalists were strongly affected. If people really knew, the war would be stopped tomorrow. But of course they don't know, and can't know. The correspondents don't write and the censorship wouldn't pass the truth. What they do send is not the war, but just a pretty picture of the war with everybody doing gallant deeds. The thing is horrible and beyond human nature to bear and I feel I can't go on with this bloody business.

(10) In 1917, Lord Northcliffe, the owner of the Daily Mail, wrote to Hamilton Fyfe, who was reporting the war on the Eastern Front.

Every article that is received from you is submitted to me; but the censor "kills" an immense amount of matter. The articles from you are "killed" I put before important members of the Cabinet, either verbally or in your writing, so that nothing is wasted.

(11) In 1917 Hamilton Fife returned to the Western Front.

My next assignment was to the British Front in France. what a contrast I found there - in the comfortable chateau allotted to the correspondents, in the officers placed at their service, in the powerful cars at their disposal - to the conditions prevailing in the early months of the war! Then we were hunted, threatened, abused. Now everything possible was done to make our work interesting and easy - easy, that is, so far as permits and information and transport were concerned. No scrounging for food: we had a lavishly provided mess. No sleeping in hay or the bare floors of empty houses: our bedrooms were furnished with taste as well as every convenience, except fitted basins and baths. But then we each had a servant, who brought in a tin tub and filled it after he had brought early morning tea.

I felt a little bit ashamed to be housed in what, after my experiences, I could not but call it luxury. It had an unfortunate result too, in cutting us off from the life of the troops. I made application soon after I arrived to be allowed to stay in the trenches with a friend commanding a battalion of the Rifle Brigade. No correspondent, I learned, had done this. They knew only from hearsay how life in the front line went on.

(12) After the war William Beach Thomas wrote about his report on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in his book, A Traveller in News (1925)

I was thoroughly and deeply ashamed of what I had written, for the good reason that it was untrue. The vulgarity of enormous headlines and the enormity of one's own name did not lessen the shame.

(13) Philip Gibbs, Adventures in Journalism (1923)

We identified ourselves absolutely with the Armies in the field. We wiped out of our minds all thought of personal scoops and all temptation to write one word which would make the task of officers and men more difficult or dangerous. There was no need of censorship of our despatches. We were our own censors.

(14) C. E. Montague, Disenchantment (1922)

The average war correspondent - there were golden exceptions - insensibly acquired a cheerfulness in the face of vicarious torment and danger. Through his despatches there ran a brisk implication that the regimental officers and men enjoyed nothing better than "going over the top"; that a battle was just a rough jovial picnic, that a fight never went on long enough for the men, that their only fear was lest the war should end this side of the Rhine. This tone roused the fighting troops to fury against the writers. This, the men reflected, in helpless anger, was what people at home were offered as faithful accounts of what their friends in the field were thinking and suffering.