Dardanelles Campaign

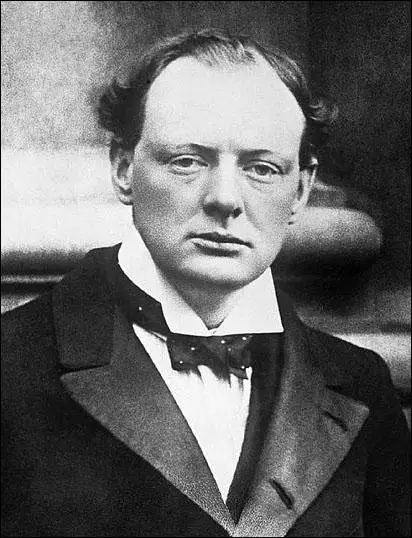

Winston Churchill was one of the first to realise that the First World War would last for several years. He was especially concerned about the stalemate on the Western Front. In December, 1914 he wrote to Asquith that neither side was likely to be able to make much impression on the other, "although no doubt several hundred thousand men will be spent to satisfy the military mind on the point." He then suggested some alternative strategies to "sending our armies to chew barbed wire in Flanders?" (1)

Churchill was also concerned about the threat that Turkey posed to the British Empire and feared an attack on Egypt. He suggested that the seizure of the Dardanelles (a 41 mile strait between Europe and Asiatic Turkey that were overlooked by high cliffs on the Gallipoli Peninsula). At first the plan was initially rejected by H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Admiral John Fisher and Lord Kitchener. Churchill did manage to persuade the commander of the British Mediterranean Squadron, Vice Admiral Sackville Carden, that the operation would be successful. (2)

On 11th January 1915, Vice Admiral Carden proposed a three-stage operation: the bombardment of the Turkish forts protecting the Dardanelles, the clearing of the minefields and then the invasion fleet travelling up the Straits, through the Sea of Marmara to Constantinople. Carden argued that to be successful the operation would need 12 battleships, 3 battle-cruisers, 3 light cruisers, 16 destroyers, six submarines, 4 sea-planes and 12 minesweepers. Whereas other members of the War Council were tempted to change their minds on the subject, Admiral Fisher threatened to resign if the operation took place. (3)

Admiral Fisher wrote to Admiral John Jellicoe, Commander of the Grand British Fleet, arguing: "I just abominate the Dardanelles operation, unless a great change is made and it is settled to be made a military operation, with 200,000 men in conjunction with the Fleet." (4) Maurice Hankey, secretary of the Imperial War Cabinet, agreed with Fisher and circulated a copy of the Committee of Imperial Defence assessment that was against a purely naval assault on the Dardanelles. (5)

Despite these objections, Asquith decided that "the Dardanelles should go forward." On 19th February, 1915, Admiral Carden began his attack on the Dardanelles forts. The assault started with a long range bombardment followed by heavy fire at closer range. As a result of the bombardment the outer forts were abandoned by the Turks. The minesweepers were brought forward and managed to penetrate six miles inside the straits and clear the area of mines. Further advance up into the straits was now impossible. The Turkish forts were too far away to be silenced by the Allied ships. The minesweepers were sent forward to clear the next section but they were forced to retreat when they came under heavy fire from the Turkish batteries. (6)

Winston Churchill became impatient about the slow progress that Carden was making and demanded to know when the third stage of the plan was to begin. Admiral Carden found the strain of making this decision extremely stressful and began to have difficulty sleeping. On 15th March, Carden's doctor reported that the commander was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Carden was sent home and replaced by Vice-Admiral John de Robeck, who immediately ordered the Allied fleet to advance up the Dardanelles Straits. (7) Reginald Brett, who worked for the War Council, commented: "Winston is very excited and jumpy about the Dardanelles; he says he will be ruined if the attack fails." (8)

On 18th March eighteen battleships entered the straits. At first they made good progress until the French ship, Bouvet struck a mine, heeled over, capsized and disappeared in a cloud of smoke. Soon afterwards two more ships, Irresistible and Ocean hit mines. Most of the men in these two ships were rescued but by the time the Allied fleet retreated, over 700 men had been killed. Overall, three ships had been sunk and three more had been severely damaged. Altogether about a third of the force was either sunk or disabled. (9)

At an Admiralty meeting on 19th March, Churchill and Fisher agreed that losses were only to be expected and that four more ships should be sent out to reinforce De Robeck, who responded with the news that he was reorganising his force so that some of the destroyers could act as minesweepers. Churchill now told Asquith that he was still confident that the operation would be successful and was "fairly pleased" with the situation. (10)

On 10th March, Lord Kitchener finally agreed that he was willing to send troops to the eastern Mediterranean to support any naval breakthrough. Churchill was able to secure the appointment of his old friend, General Ian Hamilton, as Commander of the British Forces. At a conference on 22nd March on board his flagship, Queen Elizabeth, it was decided that soldiers would be used to capture the Gallipoli peninsula. Churchill ordered De Roebuck to make another attempt to destroy the forts. He rejected the idea and said that the idea that the forts could be destroyed by gunfire had "conclusively proved to be wrong". Admiral Fisher agreed and warned Churchill: "You are just eaten up with the Dardanelles and can't think of anything else! Damn the Dardanelles! they'll be our grave." (11)

Arthur Balfour suggested delaying the landings. Winston Churchill replied: "No other operation in this part of the world could ever cloak the defeat of abandoning the effort at the Dardanelles. I think there is nothing for it but to go through with the business, and I do not at all regret that this should be so. No one can count with certainty upon the issue of a battle. But here we have the chances in our favour, and play for vital gains with non-vital stakes." He wrote to his brother, Major Jack Churchill, who was one of those soldiers about to take part in the operation: "This is the hour in the world's history for a fine feat of arms, and the results of victory will amply justify the price. I wish I were with you." (12)

Asquith, Kitchener, Churchill and Hankey held a meeting on 30th March and agreed to go ahead with an amphibious landing. Leaders of the Greek Army informed Kitchener that he would need 150,000 men to take Gallipoli. Kitchener rejected the advice and concluded that only half that number was needed. Kitchener sent the experienced British 29th Division to join the troops from Australia, New Zealand and French colonial troops on Lemnos. Information soon reached the Turkish commander, Liman von Sanders, about the arrival of the 70,000 troops on the island. Sanders knew an attack was imminent and he began positioning his 84,000 troops along the coast where he expected the landings to take place. (13)

The attack that began on the 25th April, 1915 established two beachheads at Helles and Gaba Tepe. Another major landing took place at Sulva Bay on 6th August. By this time they arrived the Turkish strength in the region had also risen to fifteen divisions. Attempts to sweep across the peninsula by Allied forces ended in failure. By the end of August the Allies had lost over 40,000 men. General Ian Hamilton asked for 95,000 more men, but although supported by Churchill, Lord Kitchener was unwilling to send more troops to the area. (14)

In the words of one historian, "In the annals of British military incompetence Gallipoli ranks very high indeed." (15) Churchill was blamed for the failed operation and Asquith told him he would have to be moved from his current post. Asquith was also involved in developing a coalition government. The Conservative leader, Andrew Bonar Law, became Minister of the Colonies and Churchill's long-term enemy, Arthur Balfour, became the new First Lord of the Admiralty. Churchill was now relegated to the post of the Chancellorship of the Duchy of Lancaster. (16)

On 14th October, Hamilton was replaced by General Charles Munro. After touring all three fronts Munro recommended withdrawal. Lord Kitchener, initially rejected the suggestion but after arriving on 9th November 1915 he visited the Allied lines in Greek Macedonia, where reinforcements were badly needed. On 17th November, Kitchener agreed that the 105,000 men should be evacuated and put Monro in control as Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean. (17)

About 480,000 Allied troops took part in the Gallipoli campaign, including substantial British, French, Senegalese, Australian, New Zealand and Indian troops. The British had 205,000 casualties (43,000 killed). There were more than 33,600 ANZAC losses (over one-third killed) and 47,000 French casualties (5,000 killed). Turkish casualties are estimated at 250,000 (65,000 killed). "The campaign is generally regarded as an example of British drift and tactical ineptitude." (18)

In November, 1915, Winston Churchill was removed as a member of the War Council. He now resigned as a minister and he told Asquith that his reputation would rise again when the whole story of the Dardanelles came out. He also criticised Asquith in the way the war had so far been managed. He ended his letter with the words: "Nor do I feel in times like these able to remain in well-paid inactivity. I therefore ask you to submit my resignation to the King. I am an officer, and I place myself unreservedly at the disposal of the military authorities, observing that my regiment is in France." (19)

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Bean, report sent to Andrew Fisher (17th May, 1915)

The Australians and Maorilanders landed in two bodies, the first being a covering force to seize the ridges around the landing about an hour later. The moon that night set about an hour and a half before daylight. This just gave time for the warships and transports of the covering force to steam in and land the troops before dawn.

It had long been known that the Third Australian Brigade, consisting of Queenslanders, South Australians, Western Australians, and Tasmanians, had been chosen to make the landing. This brigade consists largely of miners from the Broken Hill and Westralian gold-fields. It had left Egypt many weeks before the rest of the force, and had landed on Lemnos Island, where the troops were thoroughly practised at landing from ships and boats. During the second week in April the greater part of the Australian and New Zealand troops from Egypt followed, and had been just a fortnight in Lemnos when they sailed to effect a landing at a certain position on the northern shore of Gallipoli Peninsula, about 60 miles away.

The covering force was taken partly in four of our own transports, partly in three battleships. The night was perfect; about three o’clock the moon set, and the ships carrying the troops, together with the three warships which were charged with the protection of the flanks, stole in towards the high coastline. It was known that the coast was fortified, and that a battery on a promontory 2 miles southwards, and several other guns amongst the hills inland covered the landing place. The battleships and transports took up a position in two lines. The troops were transferred partly to the warships’ boats, and partly to destroyers, which hurried in shore, and re-transferred their occupants to boats, which then made by the shortest route for the beach.

It was eighteen minutes past four on the morning of Sunday, 25th April, when the first boat grounded. So far not a shot had been fired by the enemy. Colonel McLagan’s orders to his brigade were that shots, if possible, were not to be fired till daybreak, but the business was to be carried through with the bayonet. The men leapt into the water, and the first of them had just reached the beach when fire was opened on them from the trenches on the foothills which rise immediately from the beach. The landing place consists of a small bay about half-a-mile from point to point with two much larger bays north and south. The country rather resembles the Hawkesbury River country in New South Wales, the hills rising immediately from the sea to 600 feet. To the north these ridges cluster to a summit nearly 1,000 feet high. Further northward the ranges become even higher. The summit just mentioned sends out a series of long ridges running south-westward, with steep gullies between them, very much like the hills and gullies about the north of Sydney, covered with low scrub very similar to a dwarfed gum tree scrub. The chief difference is that there are no big trees, but many precipices and sheer slopes of gravel. One ridge comes down to the sea at the small bay above mentioned, and ends in two knolls about 100 feet high, one at each point of the bay. It was from these that fire was first opened on the troops as they landed. Bullets struck fireworks out of the stones along the beach. The men did not wait to be hit, but wherever they landed they simply rushed straight up the steep slopes. Other small boats which had cast off from the warships and steam launches which towed them, were digging for the beach with oars. These occupied the attention of the Turks in the trenches, and almost before the Turks had time to collect their senses, the first boatloads were well up towards the trenches. Few Turks awaited the bayonet. It is said that one huge Queenslander swung his rifle by the muzzle, and, after braining one Turk, caught another and flung him over his shoulder. I do not know if this story is true, but when we landed some hours later, there was said to have been a dead Turk on the beach with his head smashed in. It is impossible to say which battalion landed first, because several landed together. The Turks in the trenches facing the landing had run, but those on the other flank and on the ridges and gullies still kept up a fire upon the boats coming in shore, and that portion of the covering force which landed last came under a heavy fire before it reached the beach. The Turks had a machine gun in the valley on our left, and this seems to have been turned on to the boats containing part of the Twelfth Battalion. Three of these boats are still lying on the beach some way before they could be rescued. Two stretcher-bearers of the Second Battalion who went along the beach during the day to effect a rescue were both shot by the Turks. Finally, a party waited for dark, and crept along the beach, rescuing nine men who had been in the boats two days, afraid to move for fear of attracting fire. The work of the stretcher-bearers all through a week of hard fighting has been beyond all praise.

The Third Brigade went over the hills with such dash that within three quarters of an hour of landing some had charged over three successive ridges. Each ridge was higher than the last, and each party that reached the top went over it with wild cheers. Since that day the Turks have never attempted to face our bayonets. The officers led magnificently, but, of course, nothing like an accurate control of the attack was possible. Subordinate leaders had been trained at Mena to act on their own responsibility, and the benefit of this was enormously apparent in this attack. Companies and platoons, little crowds of 50 to 200 men, were landed wherever the boats took them. Their leaders had a general idea of where they were intended to go, and once landed, each subordinate commander made his way there by what seemed to him to be the shortest road. The consequence was that the Third Brigade reached its advanced line in a medley of small fractions inextricably mixed. Several further lines of Turkish trenches were swept through. On the further ridges the Turks did not wait for the bayonet, and when at sunrise ships bringing the first portion of the main body arrived and steamed slowly through the battleships to disembark the men, those on board could see figures on the skyline of the ridges near them, and on a further ridge inland. Presently a heliograph winked from near the top of the second hill. They were our men. They could be seen walking about and digging just as you see them any morning at Liverpool Camp during annual training. The relief which flooded the hearts of thousands of anxious watchers on the ships can be better imagined than described.

(2) Raymond Gram Swing, Good Evening (1964)

It is more than a guess that the outcome of World War I - and much more - turned on the role of Turkey. Had the crumling Ottoman Empire, then under the rule of the Young Turks, been an ally of Great Britain, it is easy to imagine that Russia could have been bolstered with adequate supplies sent through the Dardanelles and the Black Sea and sustained itself against the attack of the German army on the Eastern front. If Russia had not collapsed, there would have been no Bolshevik revolution, certainly not in 1917, and the rapid growth of Communism would have been deferred and its future altered. International relations everywhere would have been totally different today.

The Allies made two tremendous efforts to overpower Turkey after the war had started. Both were inspired by Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty. It is one of the galling ironies of his history that Churchill virtually vetoed a British-Turkish alliance shortly before the war. He had visited the Young Turks in Constantinople in 1909, and when a Young Turk delegation went to London in 1911 to seek a British alliance, this was turned down, largely through Churchill's influence. The Young Turks, under Enver and Talaat, had ceased to be an attractive social force and had degenerated into a corrupt and decaying oligarchy, which is an excuse for Churchill's judgment - save that history does not excuse consequences, and the British decision was one of the most fateful made in modern times.

(3) Eric Bogle, The Band Played Waltzing Matilda (c. 1960)

When I was a young man I carried my pack

And I lived the free life of a rover

From the Murrays green basin to the dusty outback

I waltzed my Matilda all over

Then in nineteen fifteen my country said son

It's time to stop rambling 'cause there's work to be done

So they gave me a tin hat and they gave me a gun

And they sent me away to the war

And the band played Waltzing Matilda

As we sailed away from the quay

And amidst all the tears and the shouts and the cheers

We sailed off to Gallipoli

How well I remember that terrible day

When the blood stained the sand and the water

And how in that hell that they called Suvla Bay

We were butchered like lambs at the slaughter

Johnny Turk he was ready, he primed himself well

He showered us with bullets, he rained us with shells

And in five minutes flat he'd blown us all to hell

Nearly blew us right back to Australia

But the band played Waltzing Matilda

As we stopped to bury our slain

And we buried ours and the Turks buried theirs

Then it started all over again

Now those who were living did their best to survive

In that mad world of blood, death and fire

And for seven long weeks I kept myself alive

While the corpses around me piled higher

Then a big Turkish shell knocked me arse over tit

And when I woke up in my hospital bed

And saw what it had done, Christ I wished I was dead

Never knew there were worse things than dying

And no more I'll go waltzing Matilda

To the green bushes so far and near

For to hump tent and pegs, a man needs two legs

No more waltzing Matilda for me

So they collected the cripples, the wounded andmaimed

And they shipped us back home to Australia

The legless, the armless, the blind and insane

Those proud wounded heroes of Suvla

And as our ship pulled into Circular Quay

I looked at the place where me legs used to be

And thank Christ there was nobody waiting for me

To grieve and to mourn and to pity

And the band played Waltzing Matilda

As they carried us down the gangway

But nobody cheered, they just stood and stared

And they turned all their faces away

And now every April I sit on my porch

And I watch the parade pass before me

I see my old comrades, how proudly they march

Reliving the or their dreams of past glory

I see the old men, all twisted and torn

The forgotten heroes of a forgotten war

And the young people ask me, "What are they marching for?"

And I ask myself the same question

And the band plays Waltzing Matilda

And the old men still answer to the call

But year after year their numbers get fewer

Some day no one will march there at all.